Tracking and prebunking US-inspired election narratives, their localisation, as well as other misinformation, conspiracy theories and scare campaigns on social media, online ads and offline efforts, First Draft’s APAC team adopted a clear-eyed, pre-emptive approach to help counter harmful information in the lead-up to the 2022 Australian election.

By Esther Chan, Stevie Zhang, Julia Bergin and Anne Kruger

Introduction

It was a six-week election campaign that felt more like six months. Ahead of Australia’s long-awaited May 21 federal poll, First Draft’s APAC team were running a fully operational, thriving misinformation monitoring engine room. ‘CrossCheck Australia: election watch’ drew together a diverse range of news media, including national and regional mastheads as well as community media — who serve groups often targeted by disinformation.

Preparation began in October 2021. We mapped out a ‘misinformation playbook’ of what to expect; devised and delivered a four-week series of master classes; trained paid interns to monitor platforms’ ad libraries; and created immersive election day simulations that helped members prepare for online threats. By March 2022, we had gathered and trained over 130 journalists and media practitioners from 18 different mastheads who joined our collaborative network via a Slack workspace. Participants were then leveraged as leaders in this field throughout their newsrooms.

We provided morning alerts and in-depth daily briefing documents. We took a pre-emptive approach to monitoring online discourse and narratives across a broad range of online and social media platforms and apps, with the aim of slowing down misinformation. Since January 2022, our work has been cited in over 50 different reports, and we provided guidance for countless others. As well as quotes directly attributable to First Draft, there were also important times when our work could not be mentioned — times when we needed to caution about amplification concerns, and help journalists develop reporting strategies where necessary.

But our work didn’t stop there. Ahead of the campaign, we pivoted to provide advice on Ukraine — which was picked up and featured for three weeks on Twitter Moments. That was bookended by news of monkeypox; with the adoption of international conspiracy theories, false voter fraud allegations, and scare campaigns aplenty in between.

Our election simulations turned out to be eerily close to what happened in reality. Read on for some of our findings.

Imported and local narratives of voter fraud

First Draft’s monitoring of online narratives throughout the election campaign found that many typical election disinformation narratives were being imported into Australia from other prior elections around the world. Most notably, many of these narratives came from the 2020 US election, which ended with former President Donald Trump and other Republican politicians claiming widespread election fraud. Similar themes circulated in an Australian context, with many falling into the three tracks First Draft previously noted:

- Disinformation intended to discredit candidates and confuse the public;

- Use of information operations to disrupt election infrastructure;

- Undermining public confidence in electoral processes after an election has taken place.

Even before the election was officially called on April 10, narratives began circulating on social media that it would be heavily impacted by voter fraud. For example, former Senator Rod Culleton, who currently leads the Great Australian Party that has been associated with social media accounts sharing election disinformation, began claiming that Dominion Voting Systems would be used in vote counting of the Australian election. Dominion was subject to various debunked conspiracy theories when results of the 2020 US election were being tallied. In response the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) quickly clarified that electronic voting would not be seen in Australia anytime soon.

Meanwhile, people were discouraged from casting postal votes due to unfounded claims that fraud or tampering would be more likely. Older people in nursing homes were told by conspiracy theorists that staff who assist them could change their votes. Voter fraud concerns were further fueled by populist radical right-wing Senator Pauline Hanson, who published videos that suggested the election could be stolen through multiple voting — something that is a punishable offence which the AEC has numerous measures against. The videos were taken down by some of the major platforms but not before they were viewed over a million times collectively. Versions of them also continued to circulate on multiple social media platforms.

Screenshot by First Draft of a Pauline Hanson cartoon with election misinformation

During this election, conspiracy theorists primarily attacked the legitimacy of the AEC. (For comparison, election administration in the US is far more decentralized. Administrators at state or local levels are responsible for running elections rather than a singular body like the AEC, hence each state’s election laws and procedures will vary.) On polling day, videos purportedly showing AEC staff providing voters with incorrect information circulated among fringe groups, including among the so-called “freedom friendly” parties. Supporters of these groups performed tests on election officials, believing themselves to be protectors of Australia’s democracy.

One such claim that has persisted even after the new Labor government was sworn in concerned the question of how many preferences were required for a Senate ballot to be valid. AEC resources, including the voting practice exercise on its website and information in their Meta ads, states that 6 votes above the line or 12 below the line are required — however, the official scrutineers handbook states that if only one box was numbered, the ballot paper would still be considered formal. In an email to First Draft, the AEC explained, “Numbering at least 1 box above the line or at least 6 below the line is technically formal thanks to vote saving provisions, but your vote will exhaust quickly and carry less weight.” This discrepancy led to social media claims that AEC staff were “intentionally committing electoral fraud”.

A similar claim that has continued to circulate online in the weeks after the election concerned the question of “blank” boxes on the Senate ballot. Independent candidates are usually grouped together at the end of the ballot, but the AEC confirmed to First Draft those running together as part of an unendorsed group are ineligible for “Independent” status and therefore are shown on the ballot under an unlabelled box. Videos and recordings purportedly showing AEC staff telling people not to number the “blank” boxes circulated during and after polling day, after being published by numerous “freedom-friendly” candidates. The validity of the recordings are being looked into by the AEC, but these candidates have accused the AEC of “giving out information that is totally incorrect, misleading voters” and even deliberately “[sabotaging] independent candidates”.

After polls closed on election day, claims of fraud during vote counting swung into full gear. Scrutineers linked to “freedom friendly” candidates circulated anecdotal accounts claiming, for instance, that the AEC committed electoral fraud by opening ballot boxes before 6 pm without scrutineers present — though ballots were sorted, not counted, between 4 pm and 6 pm. Others declared that there was a “gross manipulation of data and a misrepresentation of the peoples vote” occurring because they observed not all preferences were being counted. The AEC explained to First Draft that the two-candidate-preferred method of counting is a way for it to conduct an initial, indicative preference count to provide the country with an indication of who will win the seat as soon as possible, adding, “This is often people leaping to conspiracy rather than taking the time to understand the count process.”

Agents of disinformation frequently framed unfounded claims of fraud at all stages of the election as “just asking questions”. This is a common tactic among conspiracy theory communities, as can achieve the aim of seeding doubt, while still preserving the claimant’s plausible deniability. Another similar tactic used in this election was “just trying to educate voters”. For example, Reignite Democracy Australia, a group that built its platform on being pro-freedom and anti-Covid-19 lockdown measures at the height of the pandemic, spread misleading messaging as part of their “voting education program” that emphasized voters should bring a pen into the voting booth, rather than using the AEC-provided pencils. The implication was that pencil might make it easier for a ballot to be tampered with; however, the AEC has measures in place to ensure that the only time someone would be alone with a vote is when the voter is in the ballot box, and more than one polling official would be watching over every step of the process. Despite the AEC’s frequent debunks on social media against this narrative, fearmongering over pencil votes still spread far and wide.

Conspiracy theory links WHO ‘pandemic treaty’ to election

False or misleading narratives about nonexistent voter fraud aside, this election was also plagued with conspiracy theories fearmongering about the purported collusion between the next Australian leader and/or leading party and a so-called “globalist” government. These baseless claims, as explained by the BBC here, are tied to a supposedly overarching global government headed by the “elites”, or more specifically, to the World Economic Forum (WEF)’s post-pandemic economic recovery initiative, dubbed the Great Reset; the WEF’s founder Klaus Schwab, described as some sort of “mastermind” behind the “globalist” agenda; or the World Health Organization (WHO)’s proposed “pandemic treaty”.

In the final weeks of election campaigning, the so-called “pro-freedom” minor parties, including One Nation and the United Australia Party (UAP), drummed up their efforts in promoting a conspiracy theory about global power grabs to the Australian election ahead of the WHO’s annual World Health Assembly (WHA). The theory states that either major Australian political party, if elected, would vote in favour of expanding the WHO’s pandemic powers, forfeiting Australian freedoms and liberties mere days after taking office. This is false. WHO member states did agree at this year’s WHA to start the process of drafting and negotiating an accord to foster a stronger global response to pandemics, and which would be complementary to a separate, US-led International Health Regulations that set the timeline for countries to discuss how they should better report on new outbreaks. However, the treaty touted as a done deal for dystopia is not going to be brought to bear — a draft is not due until 2024.

Tracking Twitter data about the yet-to-be-drafted treaty in the days leading up to the election, we found the unique URL of a One Nation petition to “Stop the WHO Pandemic Pact” was the most shared web page included in tweets globally. In fact, the hashtag #StoptheTreaty was trending on the platform immediately before and on election day in countries such as Australia, the UK and the US.

Visualisation by First Draft using Trendsmap data on #StoptheTreaty May 16-21, 2022

The UAP, meanwhile, spent on a series of Facebook and YouTube ads falsely claiming China would soon lock Australia down because “Liberal and Labor are transferring Australian health” to a China-controlled WHO “a day after the election”. Combined, the ads registered over a million impressions on Meta and upwards of 5 million views on YouTube. Neither platform found this claim to be in violation of their policies. At the same time, the UAP sought to spam voters with mass text messages in a last-ditch pitch to secure support, as seen in the screenshot below:

Screenshot by First Draft

Scare campaigns amplified by texts and offline efforts

It’s not the first time the UAP has attempted to reach prospective voters with unsolicited political text messages. The UAP shows how a conspiracy theory can spread from mainstream social media platforms to various corners of the internet, as well as other forms of digital mass communication such as texts. While the election results, which did not give “pro-freedom” parties a single seat in the lower house, signaled a clear referendum on such rousing rhetoric, the ability for conspiracy content to retain an online presence and reach voters in texts — an opaque space to monitor — facilitates the spread of misinformation.

In fact, efforts to smear candidates on character grounds, such as negatively associating them with foreign powers were not just reported online but also on the street. Conspiracy theories also featured in offline material, authorised and printed on corflute signage. In Australia, pending political ads come with a disclaimer, they can display whatever they desire. The Australian Electoral Commission has however been clear that it “has no role in regulating the political content of electoral communications”.

Geo-political implications

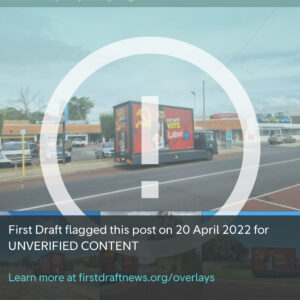

First Draft has noted previously the impact of Australia and China’s deteriorating relations on domestic politics, particularly on the local Chinese diasporic population. This election proved to be no exception, with both major and minor parties rolling out aggressive claims that, for instance, one candidate is particularly favored by the Chinese government, or a vote for one candidate means a softer stance on China. These claims featured heavily in offline political advertising, including the conservative advocacy group Advance Australia’s use of mobile billboards featuring a photo of Chinese President Xi Jinping, who is portrayed as voting for Labor. This is part of the group’s attempt to promote the “reds under the bed” rhetoric against Labor across the nation.

Screenshot of an April 19, 2022, Facebook post by Advance Australia

A similar scare campaign was also launched against the Liberal Party, targeting Hong Kong-born unsuccessful candidate for Chisholm Gladys Liu. Liu, who was elected to Parliament in 2019 amidst controversy, was branded a Chinese spy on the official Facebook page of Labor’s Queensland state branch and accused of “taking money from the Chinese government” at a community debate by Drew Pavlou, an outspoken critic against the Chinese Communist Party and failed candidate for the Queensland Senate. Pavlou and his Democratic Alliance ran roving billboards labelling Liu “Xi Jinping’s candidate for Chisholm” and encouraging voters to “flush the Liu”. He also called South Australian Senator Nick Xenophon “China’s Puppet” in a similar truck for his legal work with Huawei and in online ads, he said Xenophon was “supporting genocide” and helping to throw Uyghurs into concentration camps.

Screenshots by First Draft of photos published by Drew Pavlou

Messages on these billboards are unverified and constitute personal attacks at best. Even though there is a lack of evidence to conclusively debunk the links between these candidates and a foreign power like China, these claims can still work to single out people of Chinese origin and reinforce stigma against the Chinese diaspora in Australia. The uptick in misleading and unverified content posing as political posturing is a reminder to voters that they should not take online or offline ads as official information.

Disinformation in online ads

Political parties and candidates paid big money throughout the election campaign to enshrine these false and misleading narratives in online ads. First Draft’s monitoring documented a treasure trove of conspiratorial content, scare campaigns, and misinformation relating to the electoral process all contained within the Australian “social issues, elections or politics” category. Whilst major parties favoured fearmongering, so-called “freedom friendly” minor parties used ads to trumpet disinformation.

Labor leaned into a scare campaign that a re-elected Liberal government would force all age pensioners onto its controversial cashless debit card scheme, whilst the Coalition preferred the narrative that a Labor government would by default be a Labor-Greens government or a Labor-Chinese Communist Party government. These false claims went hand in hand with a big advertising push to incriminate Independents as incognito Greens. The AEC said in a May 16 statement that signage authorized by Advance Australia falsely depicting Zali Steggall and David Pocock as Greens candidates is in breach of section 329 of the Electoral Act. Both major parties were guilty of using misleading (albeit legal) content to bolster their mailing lists. An avalanche of ads linked users to custom Liberal and Labor party postal vote registration websites in a bid to siphon their data directly into respective party headquarters.

As noted above, One Nation, UAP, and other fringe parties also used online ads, meaning conspiracy theories that were once confined to the corners of closed chat apps and semi-closed spaces were served up for public consumption. There were repeated references to the WEF and Great Reset, alongside claims that major parties and their candidates were “pawns” and “puppets” in a grand global scheme. There was also an abundance of ads promoting anti-vaccination sentiments, including declarations of “medical apartheid”, references to the 1947 Nuremberg Code, and calls to try the government for “treason”.

The intercontinental authoritarian angle had no bounds, applied to all manner of local electoral issues. Preference deals and how-to-vote cards were deemed the work of “shrills for the globalists”, although these ads usually concluded with instructions on how-to-vote for [insert pro-freedom minor party here]. Often these ads were videos of lengthy speeches delivered by candidates in community forums, rambling with false and misleading claims.

The UAP spent big on Meta advertising in the lead up to the Australian federal election (in excess of $1.2 million between March 1 and the May 21 election) and as a result their paid content often surpassed the one million impressions mark. Their YouTube audience numbers were just as large. Many other advertisers in narrative lockstep only garnered a small audience, but notwithstanding the low engagement of individual ads, the sheer volume of them allowed for an unprecedented pile up of false and misleading content.

Lessons from the 2022 Australian election

Election misinformation has become a fixture in any formal, organised group decision-making process since narratives alleging fraud were popularised during and after the 2020 US election. Claims about purported voter fraud and the various ways electoral systems and processes could be rigged have transcended geographical boundaries, repeated and localised not just in Australia but also various elections and political events around the world, such as the Myanmar coup last year, the French and Philippines’ presidential elections this year, and the upcoming one in Brazil later this year.

For authorities and newsrooms seeking to counter local narratives inspired by the pre-existing ones from other elections, it is key to educate the public about possible disinformation and prebunking those claims just as they start to emerge online. For the 2022 Australian election, First Draft provided exclusive research briefs with our CrossCheck communities with prebunks about postal vote, pre-poll and preferential voting systems — areas where confusion was apparent. While credible information is aplenty on the AEC website and social media, a void could still exist for those who may not know how to navigate these platforms, or those whose first language is not English. That being said, the AEC has run a highly successful campaign countering the slew of disinformation, maintaining a steady Twitter presence that not only quickly addressed voters’ questions, but also had a sense of humor. Continuing this style of education will be effective, primarily because the election commission was speaking to people on their terms — the aim in the future should be to expand on this ability, such as appearing on other platforms and other languages. Researching and drafting prebunks will also help prepare journalists to pre-emptively tackle problematic narratives before they gain traction online. They can also then incorporate elements of the prebunks in their publications to protect their audience against harmful narratives that are starting to gain traction.

In order to surface emerging narratives and study the risks they potentially carry, consistent, systematic online monitoring is imperative. First Draft’s daily monitoring of mainstream platforms, semi-closed spaces such as Telegram, Gettr, Discord and Parler, as well as fringe forums including 4chan and Kiwi Farms have unearthed some of the most popular misinformation narratives about the election, how they evolved across platforms and over time, and allowed a more comprehensive picture to be painted. Thanks to our team’s language capabilities, we were also able to track narratives of concern circulating in the Chinese-language communities via apps such as WeChat. Local knowledge, cultural understanding and monitoring of popular Chinese-language publications also supplemented our analysis.

Conspiracy theories that fearmonger about a government working against people’s interest and conforming to a purported globalist agenda, as outlined in this piece, echoed those popular at the height of the pandemic as well as QAnon theories that the world is run by a cabal of paedophiles. Having lived in uncertainty and a shortage of clinical data, while being bombarded by deliberate promotion of false claims about Covid-19 and the vaccine over the last two years, it is expected that a portion of the population may have been swayed by conspiracy theories. One of the reasons being that unverified claims, which are highly emotionally charged, work well to persuade those who are starting to lose faith in who they have been told to listen to, in the face of a once-in-a-century pandemic. In the context of the election, groundless claims disguised as efforts “exposing” evil forces against the people and fighting for our collective rights and freedoms could be a powerful means to sow doubts and influence hesitant voters. Since we as humans naturally react to and remember negative, unfounded theories, especially those that carry a grain of truth, it is an easy tactic to use.

Key takeaways from tracking and analysing misinformation about the 2022 Australian election include the need for methodical monitoring and analysing of misinformation; well-timed, thorough prebunking; the flagging of new tactics used to spread disinformation and countering them with timely, accurate facts, sometimes making use of social media, such as a quick Twitter thread debunking myths, can be the best approach. Our work on countering misinformation is also facilitated by the community of over 100 journalists with whom we share the first signs of online abnormalities, because mitigating election disinformation requires a collaborative effort.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.