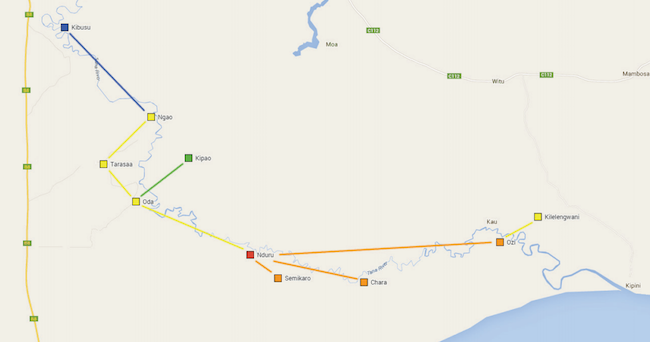

Last August, a fisherman living near Nduru, Kenya went missing. Locals feared he had been murdered, and rumors about his fate began to spread eastward from Nduru to the villages of Semikaro and Chara.

But the rumor’s spread did not trace a logical path from one close village to the next. The villages of Ngao and Kipao are near each other, but the latter didn’t hear about the fisherman until a day after the rumor hit Ngao. By that time, people in villages much farther away had already heard about the missing man.

Why did the rumor seemingly skip Kipao? A Canadian NGO called The Sentinel Project knew the answer.

Two years earlier, in 2013, a small group of Sentinel Project election observers were deployed in Kenya’s Tana Delta Sub-County. The region had seen bloody massacres between the agriculturalist Pokomo and the pastoralist Orma tribes in the months before the election and misinformation was rampant, affecting daily life in the region.

“The team discovered that misinformation (incendiary ‘organic’ rumors and deliberately-spread disinformation) had driven the fear, distrust, and hatred that enabled violence between the Orma and Pokomo ethnic groups,” wrote members of The Sentinel Project in a report published late last year.

After the election, the Sentinel Project received funding for a two-year pilot project to collect, track, and verify rumors in the area, and to test how to spread reliable information to the local communities. They called it Una Hakika, Swahili for “Are you sure?”

Drew Boyd, director of operations for The Sentinel Project, said rumors were more likely to spread between villages “that had a closer ethnic composition or less direct history of conflict”, even if they were further away, than between geographically closer villages with differences.

A visualization of the spread of the rumor about the fisherman. Key: Red (day one), Orange (day two), Yellow (day three), Green (day four), Blue (day five). Screenshot from Una Hakika final report

Ngao is primarily inhabited by members of the Pokomo tribe. Residents of Kipao are of the Orma tribe. So when the rumor of the missing man began to spread, the fraught relationship between the tribes meant residents of Kipao heard nothing from their neighbours in Ngao, and instead learned of the rumor only after it had traveled further and reached a fellow Orma village.

Una Hakika concluded its first phase last year and published a final report that provides a fascinating case study of how rumors spread by mouth and via more modern means such as text messages and the web. The project offers valuable lessons about how to create a community and technological framework to counter misinformation, and how to build trust in a new service.

As shown by the fisherman example, Una Hakika also illustrates how different barriers can prevent information flow, and how pre-existing tensions, beliefs and prejudices help birth and spread rumors.

Fertile ground for rumors

Roughly a century of rumor research has shown that rumors are birthed and spread in contexts where fear, distrust, threats and lack of information exist.

In ‘Rumor Psychology: Social and Organizational Approaches’, psychologists Nicholas DiFonzo and Prashant Bordia define a rumor as “unverified and instrumentally relevant information statements in circulation that arise in contexts of ambiguity, danger, or potential threat and that function to help people make sense and manage risk.”

As a result, rumors flourish in war zones and during natural disasters. Hurricane Katrina left in its wake a multitude of false rumors. More recently, the refugee crisis has caused numerous false rumors to spread in Europe. There is now a dedicated project, HoaxMap, that tracks and attempts to verify or debunk refugee rumors. As of this writing, they have evaluated over 300 refugee rumors, the vast majority of which are false, and which reflect the fears some have that refugees will commit violence, or exploit state aid.

In the Tana Delta, the tribal rivalry and lack of access to news and information combined with other societal and geographical forces to create a perfect environment for rumors to flourish.

The system: Humans and tech

Una Hakika’s goal was to create a system that would do three things: enable anyone in the Tana Delta to report a rumor they had heard; use human and technological means to collect, analyze, and verify rumors; and disseminate credible information about the rumor to the people affected by it.

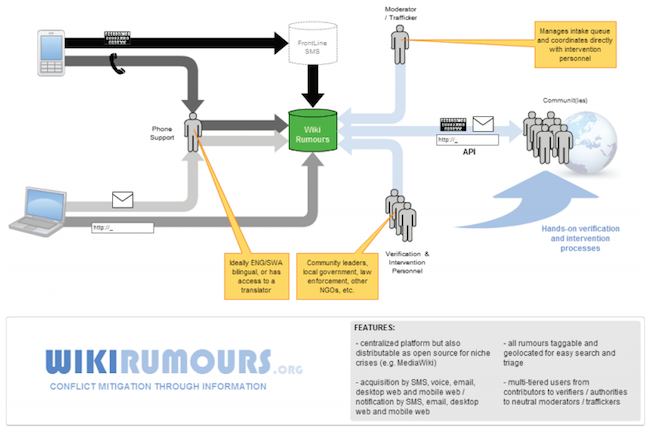

This diagram shows how information flowed into Una Hakika from the local community and then back out again:

Una Hakika gathered rumors through a range of media. Screenshot from Una Hakika final report

The system relied on SMS, phone and email, custom-built rumor logging software (“WikiRumors”), staff on the ground in the community, as well as the recruitment of community ambassadors who helped submit rumors and disseminate reliable information.

The process had four main components:

- Intake. People could use phone, SMS, email, and web to inform Una Hakika of a rumor they had heard. Those who used a phone to call in a report could speak to an operator who would collect the information. Once entered in the system, each report was stored in the ‘WikiRumours’ database with details on the nature of the rumor and the location of the report. Anyone who reported a rumor would be given a rough timeframe in which they could expect an update or reply from Una Hakika.

- Moderation/Intervention. Moderators monitored the queue of rumors and assigned people to intervene and verify them. WikiRumours software helped track all reports of a specific rumor as it spread and morphed. But as with all verification, human legwork really drove the process. Once assigned a rumor, the intervener “looks at the location and content of the rumor, which then informs the selection of the best information sources for finding out the facts,” Boyd said. They might turn to the Red Cross, local police, and community ambassadors to help gather information locally. Interveners talked to people, gathered information and watched the spread of the rumor thanks to data coming into WikiRumours. “Overall, we emphasize having multiple sources before making a determination on a given rumor,” Boyd said.

- Dissemination. As it gathered information, the team disseminated updates about a rumor to anyone who reported it, and to the affected communities. This involved “reporting the results of the verification process and providing neutral, accurate, verified information back to the communities from which a given rumor was reported as quickly as possible,” according to the Una Hakika final report. They typically used the same communication channels people reported the rumors through to send out updates.

- Analysis. The team built mapping and visualization tools into WikiRumours to analyze the aggregate data in the hope of identifying trends. “One of the goals of visualization and mapping is to better understand how different types of rumors spread through a population in relation to geographical, demographic, and other factors,” the report said.

Over the course of two years, Una Hakika conducted over 350 investigations and interventions of rumors, recruited roughly 200 “community ambassadors” who helped report rumors and disseminate credible information, and built up a subscriber list of more than 1,500 people who received updates via SMS about rumors affecting their area.

The subscriber number may seem small, but it represents 1 in 15 adult mobile phone users in the Tana Delta. The team’s research also found that each subscriber on average shared the information with 30 other people.

Remarkably, Una Hakika managed to develop enough trust with local communities that people began to share rumors they heard, and also to help spread updates from the project with their friends, family and others in their community. That level of engagement is something any media company would be happy to have. Una Hakika achieved it thanks to an early and ongoing effort to build trust in the region.

Becoming part of the community

Boyd said one of their most important early trust-building activities was to integrate people from the local communities into the project.

“We can’t emphasize enough how much that building trust is one of the most difficult yet critical initial and ongoing tasks associated with this kind of work,” he said.

He compared it to building a house in the community.

“Bring in your own ideas and expertise but work with the community so that they can make the project their own,” he said.

The design of the project called for the involvement of locals as community ambassadors, and it required them to hire local staff to collect and verify rumors. Una Hakika would have failed if the team was unable to encourage people to report rumors, and to sign up for SMS updates about rumors affecting their area.

Boyd said they took a deliberate approach to introducing themselves to the local communities.

“Integration began from the very beginning by following the culturally accepted customs of introduction,” he said. “These are not especially complicated or exotic customs but they helped to situate the project in the local context rather than reinforcing the idea that these are foreign ideas. That meant doing things like going to the local administration, having them give us contact information for the village chiefs, then going directly into the communities and meeting with the people, and on from there.”

Their goal was to have “the project and staff be community members rather than strictly a sort of service provider”.

Educating people about rumors, and the importance of questioning them

One immediate challenge was communicating what was meant by a “rumor”. Christopher Tuckwood, executive director of The Sentinel Project, called it a stumbling block for many people, similar to previous research into how news websites report on rumors.

Tuckwood said they spoke to people about “unverified information or misinformation”. They explained that the project was focused on “converting the unknown into the known”.

Early on, he said, they saw people report verified incidents to the project, but that dissipated over time thanks to education efforts. At the outset, Una Hakika learned via a survey that most locals did not take steps to verify the information they heard. But by the end of the two-year project, many more people were engaging in verification. They began to question and interrogate what they heard, which in and of itself is a major victory.

“At the outset residents often heard unverified information but did not make efforts to ascertain the accuracy of this information,” Tuckwood said. “This was largely due to there simply being no real means to verify information that didn’t involve more hearsay. By the end of the project residents reported encountering less unverified information while dramatically increasing the rate at which they took verification into their own hands.”

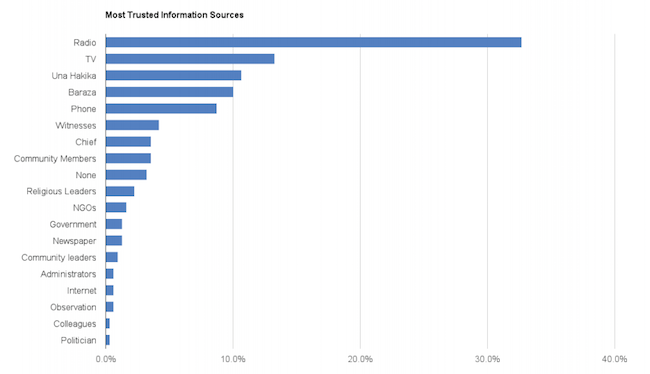

By the end of the project, a new survey also found that residents rated Una Hakika “as one of the most trustworthy sources of information for residents of the Tana Delta, ranked behind only radio and television,” according to the report.

Judging the accuracy of rumors and sources

The longer a project like Una Hakika runs, the more data it can collect and analyze about rumors. The hope is that one day this data can help inform predictive analysis that enables the system to automatically flag rumors that appear highly suspicious, or highly probable.

“Over time, we will be interested to see how the content and verification categories of different rumors match up and whether there may be factors that seem to predict rumor accuracy,” Tuckwood said.

But he also acknowledged that predicting rumor accuracy is difficult. “Often reports will be unbelievable on their face but investigation is the only way that we make a determination, regardless of our personal estimations.”

The most accurate source of rumors was not one particular organization or person, however. Rather, it was the “aggregate resident” — the entire community of locals who took the time to call, text or email in the rumor they heard.

“Essentially, each individual has their own perspective and opinions which shape their reports,” Boyd said. “But when enough separate views are collected and cross-referenced with other data, the most reliable source was the residents themselves when taken as a whole.”

This was the case with the rumor of the missing fisherman – at the core of the rumors was the claim that he had been murdered. Three days after Una Hakika received its first local rumor report, his body was found with machete wounds.