This article is part of First Draft’s coronavirus resource hub and a series on health misinformation.

While the coronavirus pandemic is anxiety-inducing for anyone, reporters, researchers and those reading up on Covid-19 every day to keep the public informed may be feeling the brunt of the information overload.

Reporting on the pandemic is a “one-two punch” of psychological pressure, said Bruce Shapiro, executive director of the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma.

On top of the nature of the story itself, with reporters interviewing survivor families, photographing victims and looking at distressing data, it can have a direct impact personally. “That combination of factors is going to make the extended story of Covid-19 challenging for a lot of journalists.”

Studies suggest that the “resilient tribe” that is journalists are better than most at coping with trauma, said Shapiro. But even at the best of times, those in the industry are at risk of developing mental health issues.

So how can journalists reporting on the coronavirus outbreak stay mentally well? The experts weigh in.

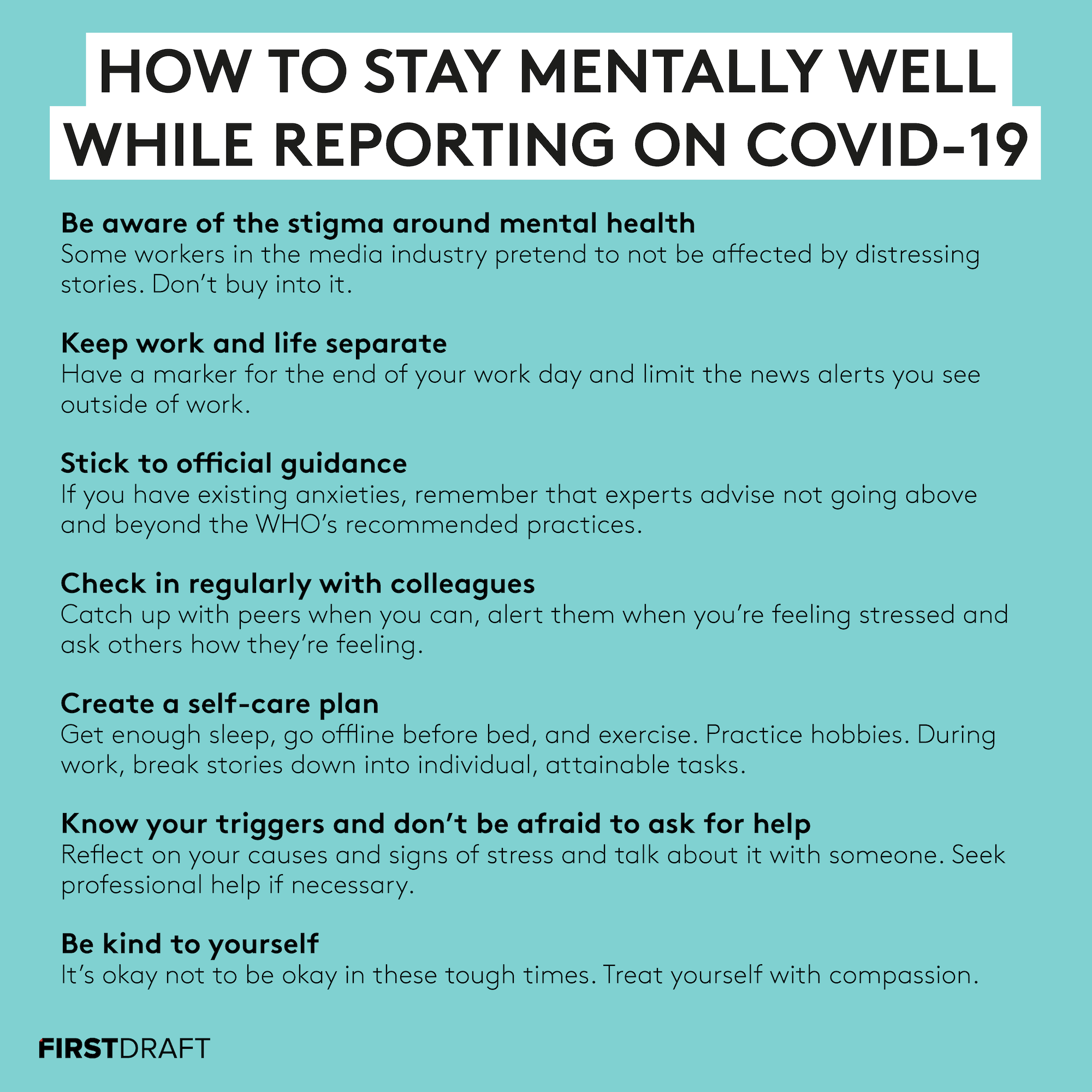

Be aware of the stigma

Vicarious trauma is common among journalists covering tragedies and instances of post-traumatic stress are higher among journalists than the general population.

Persistent high levels of stress corrode resilience, performance, and can lead to burnout. But journalism “lags behind other professional worlds in discussion of mental health issues”, said Philip Eil, a freelance journalist based in Providence, Rhode Island who has written extensively on the intersection of journalism and mental health.

Reporting requires bravery but too often journalists have mistaken this for bravado, pretending to take death and destruction in their stride. This has led to a discomfort around the discussion of mental health and emotion in some corners of the industry.

“[Taking care of yourself] is about being a good journalist” – Philip Eil, freelance journalist and mental health advocate

“There’s so much about journalism itself that would take a healthy person and make them stressed, anxious or depressed,” said Eil, who has experienced anxiety, depression and burnout through his work. “And that’s totally okay.”

He advises journalists struggling mentally while covering the coronavirus to be aware that there is a stigma but that mental health issues are not illustrative of professional competence.

“Know this work is likely to have an effect on you and be okay with that,” said Eil. “Don’t buy into the toxic and dangerous stigma that is pervasive in the world and profession.”

Separate work and life

Experts advise people struggling with anxiety in this testing time to disconnect from the news. This can be almost impossible for journalists, who – literally – live the news. But it is possible to draw a clearer line between work and home life.

“When you’re with your friends or family, have designated periods where work discussions are not allowed or during which you ban all discussion about the virus,” said Rachel Blundy, senior editor at AFP Fact Check based in Hong Kong. Her team has been at the forefront of fact checking coronavirus misinformation but she has been trying to “continually discuss” with them how to avoid becoming drained by the coverage.

“I want everyone to feel like they can switch off when they are not at work” – Rachel Blundy, Senior Editor, AFP Fact Check

“Evenings and weekends are really our own,” she told First Draft. “We now only use Slack for work discussions, where previously we used WhatsApp. This has helped to create a clearer line between work and social time. I want everyone to feel like they can switch off when they are not at work.”

Limit the content you see outside of work hours. If you must have breaking news push alerts on your mobile device, choose just one outlet to receive them from, not a dozen. Unsubscribe from newsletters that use alarmist subject lines or fill you with pangs of anxiety when they pop into your inbox.

Eil believes disconnecting from work in your personal time to look after yourself is “part of being the best journalist you can be”.

“Journalists want to stay up to date with their beat, but to be a top flight journalist you have to take care of your mind and body, otherwise it’s going to crash,” he told First Draft. “This is an investment in yourself as a journalist.”

Stick to official guidance

People already experiencing mental health problems are especially vulnerable during emergencies. For reporters already prone to anxiety, including health or contamination anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) or work-related stress, the global focus on the virus is likely already hitting especially hard.

From hand-washing to disinfecting surfaces and not touching your face, official guidelines can sound similar to OCD thoughts. It’s important to follow authoritative advice for protecting yourself and others from the virus, but also to know that it is not necessary to go above and beyond recommended practices. Know the key facts without overthinking symptoms or precautions, Eil recommended.

“You want to be prepared and vigilant,” said Eil. “But you want to maintain sanity.”

The Committee to Protect Journalists has guidelines for reporters on the ground to keep themselves safe from coronavirus.

If you already struggle with health anxiety, contamination anxiety and/or OCD, remember that it is sufficient to stick to official hygiene guidelines. Image: Pixabay.

Check in regularly with colleagues

As more countries encourage social distancing to prevent the spread of Covid-19, digital newsrooms are increasingly adopting remote working practices. But this means journalists are more at risk of isolation at a time when many feel they are working more and with a story that can be relentless.

“Social isolation is one of the risk factors for physiological distress, and social connection and collegial support is one of the most important resilience factors,” Shapiro told First Draft, citing research into journalists covering trauma.

One of the best resources journalists have at this time is each other, said Eil. “For many of us who have friends, spouses who are not in journalism who don’t understand the specific kind of stress we go through, it can be enormously therapeutic to speak to colleagues who know what we’re doing.”

Convene with colleagues when you can and alert them if you’re feeling stressed. Try talking about something unrelated to coronavirus or ask others how they’re feeling.

For freelancers or other journalists without a network of colleagues, Eil said he is happy to discuss the issues with anyone who contacts him.

Create a self-care plan

“Whether or not your beat is coronavirus… every journalist needs a self-care plan to get through this period,” said the Dart Center’s Shapiro. “We need to cover our self-care bases in order to do the job well.”

First the vitals: get enough sleep, go offline before bed, eat well and exercise. Outside of work, do “whatever you can to get coronavirus out of your head”. Put down your phone, find or practice a hobby, read a good book, watch television, meditate, write in a journal, take a bath or socialise, even if it’s just through video calls.

You have to prioritise self-care, Eil added. “Journalists are so strapped for time, but put active measures to look after yourself on your to-do list and try to work them into being non-negotiable parts of your schedule.”

Though it’s difficult, with the topic dominating most conversations, avoid excessive chat about the crisis when with family and friends if you can. Mute the WhatsApp group if you’re feeling anxious.

“Every journalist needs a self-care plan to get through this period” – Bruce Shapiro, Executive Director, Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma

While at work, Shapiro recommends breaking stories down into one-step-at-a-time reporting problems to avoid being overwhelmed.

Blundy suggests journalists have downtime during the day and try to read about other news topics as much as possible. “In Hong Kong, we take regular breaks and try to ensure we are not working lots of overtime,” she said. Have a full hour at lunch to do something unrelated to work, if possible.

A little harder for many journalists: spend less time on Twitter. “It can be unhelpful and will make you feel like you’re constantly working even when you’re not supposed to,” said Blundy.

A quick thread of @phileil-approved reading suggestions for easing anxiety during troubled, and/or quarantined, times. (These are some of my favorites, and I welcome your recs as well!)

1. @matthaig1‘s “Notes on a Nervous Planet.” https://t.co/p5XICY6IB4

— Philip Eil (@phileil) March 11, 2020

Have a marker for when the work day is done: splash your face with water, pick up an instrument, go for a walk or run, write down a summary of your day, anything you can do to mentally “sign off”.

“We need clear bookends that say work time is over,” said Shapiro.

Know your triggers and don’t be afraid to ask for help

All journalists should reflect on their own causes and signs of stress, said Shapiro.

Think about or write down the habits you adopt when you’re stressed or anxious, so if you start to slip, you can review your self-care plan, talk to someone close or seek professional help.

“If we have existing issues like OCD, anxiety, bipolar or anything, we may need to build in some added protections and sources of help to protect ourselves,” Shapiro added. “If you’re someone for whom therapy has been helpful, now is a good time to talk to somebody.”

With the coronavirus pandemic likely to continue for months, Eil also recommends therapy. “Because it’s wrapped up in stigma, people think it’s for people who are weak or mentally ill. But it’s really to be the best self and journalist you can be.”

He added: “Journalists are these high performing athletes. For them not to have therapists is like having a professional sports team with no trainer on the sidelines.”

Many workplaces have counselling services for employees, but for those without that option you can ask your healthcare provider or see what help is available locally. Online assistance may be more fitting in what Eil calls the “era of quarantine”.

Be kind to yourself

“Journalists have a tendency to be perfectionists, ambitious, workaholics,” said Eil. But it’s important for journalists to treat themselves with compassion, he said.

“In these extraordinarily stressful and scary times it’s okay to feel scared, it’s okay to feel stressed, that is a perfectly normal reaction to a really unprecedented crisis.

“Go easy on yourself because these are really tough times.”

Further reading

- Covering Coronavirus: Resources for Journalists (Dart Center)

- How journalists can fight stress from covering the coronavirus (Poynter)

- Coronavirus: 5 ways to manage your news consumption in times of crisis (The Conversation)

- How to Deal With Coronavirus If You Have OCD or Anxiety (Vice)

- Self-Care Amid Disaster (Dart Center)

- Managing Stress & Trauma on Investigative Projects (Dart Center)

- Journalism and Vicarious Trauma (First Draft)

- For reporters covering stressful assignments, self-care is crucial (Center for Health Journalism)

- Editor Perspective: Self-Care Practices and Peer Support for the Newsroom (Dart Center)

- Coronavirus: how to work well from home (Leapers)

Clarification: We have updated this article to clarify that the advice to adhere to recommended practices for preventing transmission comes from Philip Eil. An earlier version of this piece had not attributed the advice to Eil.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by subscribing to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.