Despite endless headlines, reports and conferences on the topic of information disorder, the global news industry remains woefully unprepared to tackle the increasingly effective and dangerous tactics deployed by those intent on disrupting the public sphere. Journalists often write about the phenomenon at arm’s length, rarely considering how the current environment requires newsrooms to integrate new skills and adapt their routines, standards and ethics in order to prevent deliberate falsehoods and coordinated conspiracy from creeping into the mainstream.

From our work at First Draft over the past few years, our most important takeaway is understanding that many agents of disinformation see coverage by established news outlets as the end-goal. Their tactics center around polluting the information ecosystem by seeding misleading or fabricated content, hoping to catch out journalists who now regularly turn to online sources to inform their newsgathering. Having their deliberate hoax or manufactured rumor featured and amplified by an influential news organization is considered a serious win, but so is finding their work the focus of a debunk. It all amounts to coverage. As Ryan Broderick reported in the aftermath of the ‘MacronLeaks’ data dump on the eve of the French election in May 2017, users on 4chan celebrated when mainstream news outlets began fact-checking the controversy surrounding Macron’s financial affairs, boasting that the debunks were a “form of engagement”. Over the past year we have seen these tactics play out in various regional contexts around the world. The platforms might be different but the techniques are the same.

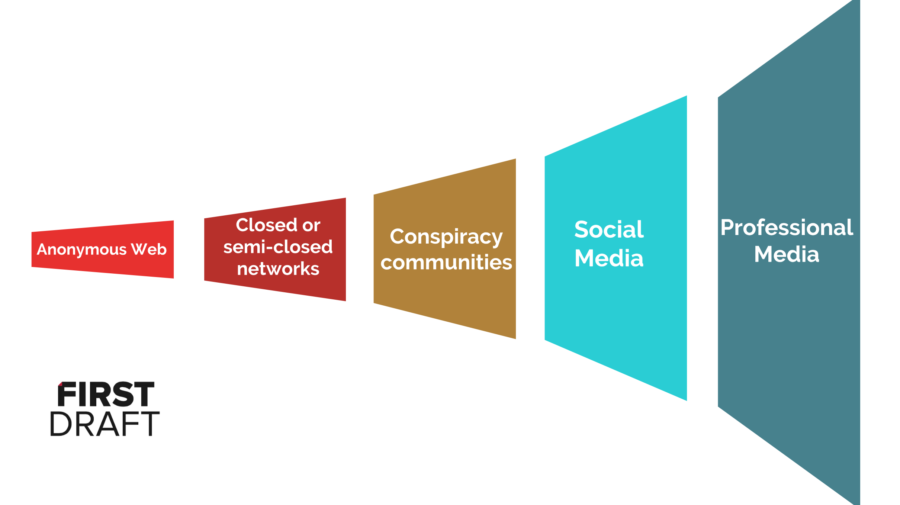

Drawing on a ‘Platform Migration’ diagram that was first created by Ben Decker, as well as the excellent work of Whitney Philips in her report, Oxygen of Amplification, I am sharing this ‘Trumpet of Amplification’. It is a simplified diagram showing the journey that disinformation often takes, as a way of kick-starting conversations in newsrooms. Disinformation often starts on the anonymous web (platforms like 4chan and Discord), moves into closed or semi-closed groups (Twitter DM groups, Facebook or WhatsApp groups), onto conspiracy communities on Reddit Forums or YouTube channels, and then onto open social networks like Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Unfortunately at this point, it often moves into the professional media. This might be when a false piece of information or content is embedded in an article or quoted in a story without adequate verification. But it might also be when a newsroom decides to publish a debunk or expose the primary source of a conspiracy. Either way, the agents of disinformation have won. Amplification, in any form, was their goal in the first place.

Efforts to undermine and explain deliberate falsehoods can be extremely valuable and are almost always in the public interest, but they must be handled with care. All journalists and their editors should now understand the risks of legitimizing a rumor and spreading it further than it might have otherwise traveled, particularly in newsrooms developing misinformation as a ‘beat’ in its own right.

Most newsrooms now have dedicated social media monitoring teams, looking for tips, sources and eyewitness content. The problem is that not all of those teams have had the training to deep dive into the provenance of the posts, images or videos they find online. Where did they originate? What was the motivation of the publisher? Unless journalists are taught to really interrogate a source, they could miss how details first appeared on Discord two weeks previously, or were part of a coordinated campaign on 4chan to amplify certain messages, or emerged as a result of tactics designed in a WhatsApp group, or a narrative honed in conspiracy communities on YouTube.

The news industry is incredibly vulnerable. There are thousands of journalists globally, many of them independently monitoring and posting on social networks every day. Convince one journalist to publish the falsehood or fabricated content, and it gets pushed almost immediately across the wider community (many newsrooms do not check reporting by other journalists or outlets with the same rigor, assuming that thorough vetting has already been completed). This is all happening just as newsrooms are being stripped of resources, but competition for clicks is fiercer than ever. And when many journalists haven’t received the necessary training in the forensic analysis of digital sources or content, it’s easier than ever to be fooled.

The flipside is also becoming increasingly easy. As an agent of disinformation, if you don’t manage to succeed in tricking journalists to reference or link to false information, try getting them to debunk it instead. A debunk is better than nothing. It provides oxygen, and oxygen means more people searching for your strategically crafted keywords online, and more people searching means more people discovering your extended networks, all pushing your ideas, narratives or beliefs. When your audience is connected, simply driving search behavior can open up your world to thousands of new eyeballs.

Doing journalism in an age of disinformation is incredibly hard, and I simply don’t think the news industry has even started grappling with the difficult questions being raised in the current environment. Here are five lessons that I hope can at least act as conversation starters in newsrooms.

1.Be prepared: train your newsrooms in disinformation tactics & techniques

In 2019, make sure your training plans include sessions on digital verification skills, but ensure they’re not just focused on assessing whether something is true or not. Make sure the participants are trained on digital provenance, so they can track where a piece of content originated. Similarly, ensure that your journalists understand how to do this type of work safely. Have they been trained in carrying out work in anonymous spaces online? Do they have high levels of personal digital security, in terms of their privacy settings, use of VPNs etc? Does your newsroom have ethics guidelines about sourcing information from closed or anonymous spaces online? Be responsible: Don’t give disinformation additional oxygen. First Draft is expanding its existing verification curriculum to cover more of this information and training in Spring 2019.

2. Be responsible: Don’t give disinformation additional oxygen

Our work suggests that there is a tipping point when it comes to reporting on disinformation. Reporting too early gives unnecessary oxygen to rumors or misleading content that might otherwise fade away. Reporting too late means the falsehood takes hold and there’s really nothing to do to stop it (it becomes a zombie rumor – those that just won’t die).

There is no one tipping point. The tipping point differs by country but is measured when content moves out of a niche community, starts moving at velocity on one platform or crosses onto other platforms. The more time you spend monitoring disinformation, the more the tipping point becomes clearer, which is another reason for newsrooms to take disinformation seriously. It is also a reason to create informal collaborations so newsrooms can compare concerns about coverage decisions. Too often newsrooms report on rumors or campaigns, for fear that they will be ‘scooped’ by other newsrooms, when again, this is exactly what the agents of disinformation are hoping for. Having every newsroom publish a QAnon explainer back in August after people turned up at Trump rallies with Q signs and t-shirts was exactly what the Q community had hoped would happen.

3. Be aware: Understand the implications of a networked audience

This is connected to the point above. Debunking or explaining these conspiracies, falsehoods or rumors, gives them not only a legitimacy, but a set of keywords for your audiences to use to search for more information. Even relatively small, disparate communities can appear significant online. Before the internet, such remote communities struggled to connect because it was so difficult to meet face to face. Now such communities can flourish. (For an excellent report into the power of keywords to shape reality, read Francesca Tripodi’s Searching for Alternative Facts).

4. Explain: Don’t act as stenographer

When so many people get their news from just tweets, Facebook posts, as headlines on Google News, or push notifications, the responsibility for how headlines are worded is more important that ever. It doesn’t matter if the 850 word article provides all the context and explanation to debunk or explain why a narrative or claim is false, if the 80 character version of that context is misleading, it’s all for nothing. Academic research shows that simply repeating the falsehood in the headline is problematic. Finding alternative ways to word a headline is difficult. We face this problem frequently at First Draft, but we have to be smarter about the ways we word headlines, tweets and posts.

5. Inoculate: Do more reporting that helps explain the issues that are often subjects of disinformation campaigns

Rather than simply reacting to the falsehoods when they appear, any reporting that preempts some of the most common and powerful narratives might help inoculate some of the disinformation. From our analysis of information in the lead up to the Brazilian and US mid-term elections, we know that the following topics are most common: attempts to undermine the integrity of the election system; attempts to sow hate and division based on misogyny, anti-semitism, islamophobia, and homosexuality; attempts to demonize immigrants; conspiracies about global networks of power.

Reporting in age of disinformation is difficult. Academic research on best practices for writing headlines is still being published and we have yet to reach firm conclusions. Newsrooms are struggling to find money for training. Most senior editors, many of whom developed their journalistic skills before digital, have no idea of the risks faced by their journalists every day. But the decisions being made by newsrooms around the world are impacting how disinformation spreads. The professional media is a critical part of the information ecosystem, and currently it is vulnerable and being used to spread false and misleading information.

I hope 2019 is the year when newsrooms start discussing how to take concrete actions to fight back, whether that is rolling out a new training course, writing new ethics and standards documents, or simply including a discussion in editorial meetings of the potential impact on the audience of reporting on disinformation.

4 thoughts on “5 Lessons for Reporting in an Age of Disinformation”