Pictures and video shared by eyewitnesses have now become a cornerstone of coverage to many breaking news events. Eyewitnesses, armed with smartphones and social media accounts, are often the best sources for footage and information from the scene.

But they are also the copyright holders of such footage, a factor that can often be forgotten in the chaos of breaking news.

“Eyewitness media can pop up in any situation,” said Adam Rendle, an specialist in trademarks, copyright and media at law firm Taylor Wessing, at the recent International Journalism Festival in Perugia. “It can trip you up and can result in having to shell some money out.”

He shared five key points journalists and news organisations should consider about copyright in breaking news, alongside Jenni Sargent, director of Eyewitness Media Hub.

Copyright verification

Figuring out who owns the copyright to a picture or a video should be part of the overall verification process, said Rendle, as “the Twitter profile you see might have the content on it, but it might not be their content to have done that with”.

“In that verification process of investigating who owns it, ie from whom shall I seek permission, the question isn’t ‘is this your video?’,” he said. “The question should be ‘did you take this video?’, as that’s the person from whom you should be seeking permission.”

Any questions of third-party rights, perhaps when looking to use a meme or “mash-up” of different materials, should also be considered, as well as any reasonable expectations of privacy for people pictured in the footage.

“This verification and these questions, the discipline has to be built into workflows and training processes,” he said.

Publishers do still need permission to use a screengrab from a video, contrary to popular opinion, and although embedding a post containing a picture or video is a “copyright-safe” way of using it, that doesn’t negate other questions around ethics or privacy.

“‘If in doubt, embed’ is a pretty useful rule of thumb,” where there are questions about copyright ownership, he said.

Permissions

The deluge of requests for contact or the use of footage faced by eyewitnesses to a breaking news event is now common sight on social media, but that doesn’t always make such use sustainable in copyright terms.

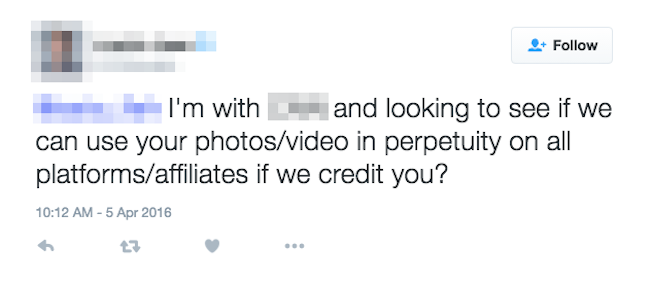

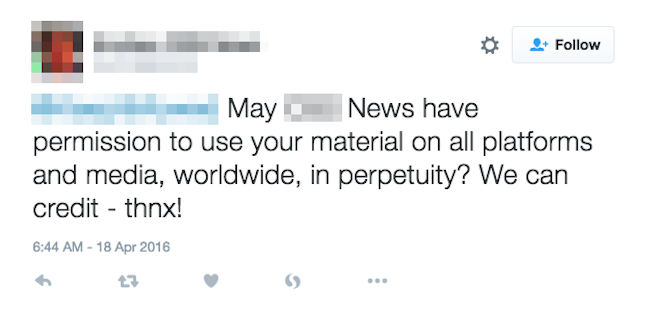

In fact, the legal jargon employed by some outlets when asking for permission to use footage, and the growth of automated requests for use are potentially self-defeating, said Rendle.

“It strikes me that these permissions requests are pretty imprecise,” he said, “and don’t give the requester the level of comfort they already want. If you’re going to go to the trouble of seeking permission you should get the permission that is going to work best for you and get the wording right.”

Phrases like “in perpetuity”, “on all platforms”,”with all affiliates” and “syndication” are regular features of such requests, but are unlikely to be fully understood by the eyewitness.

Some recent examples of requests for footage use from journalists, requests full of unclear legal jargon

“That’s the not the kind of word people in a crazy breaking news situation would understand,” he said, “and it strikes me that if you are confusing people and they are not giving the most informed consent, that’s only going to cause problems later on.”

Eyewitnesses have every right to withdraw the permission they give on social media at a later date, and if the initial wording is not clear then the likelihood of withdrawing permission is more likely.

Some eyewitnesses are becoming more savvy to the importance of their footage to news organisations, however. One eyewitness to the bombing at Maalenbeek metro station in Brussels last month aimed to pre-empt the requests by giving a blanket permission to journalists, but that practice is not without its problems.

To all press – please feel free to use any photos or video that I post on Twitter or Facebook, crediting myself and @EurActiv.

— Evan Lamos (@evanlamos) March 22, 2016

A potential solution could be to promote a hashtag for breaking news situations in which eyewitnesses mark footage for use by news organisatons, suggested Sargent.

“If we can get that as popular as #ff for ‘follow friday’ and the eyewitnesses use the hashtag #usefornews then all you have to do is set up a Tweetdeck column with #usefornews and no one needs to be bothered ever again,” she said.

“We joke about that but there might be something in it in terms of educating eyewitnesses in what they need to do to control their own rights, particularly during a breaking news situation and how comfortable they are so they don’t receive these requests.”

This is still not legally binding however, so where possible a clear and written legal agreement should be established between an eyewitness and a news organisation.

“Newsrooms can rely on [permissions on social media] insofar as it remains live,” said Rendle, “whether it’s binding is a different matter. It would be open to Evan [Lamos, in Brussels] to withdraw his permission later down the line as there’s not been a binding agreement reached.”

Don’t rely on fair dealing and fair use to get out of copyright claims

The wording around what constitutes ‘fair dealing’ or ‘fair use’ as a legal defense to a copyright claims can vary in different regions, said Rendle, but the “take home message” is “it’s not good enough to say ‘I’m reporting the news therefore I don’t need permission because I’ve got fair dealing or fair use’.”

There needs to be a public interest in using a particular picture, and its use has to be relevant to a newsworthy current event.

“A decision [to use a picture without permission] in the immediate aftermath of a breaking news situation… might be entirely defensible in the public interest,” he said. “But to be using it a couple of weeks down the line still, the exception may well fall away.”

Another important element in fair dealing is whether a video was intentionally made available to the public. One of the most famous videos from the recent attacks in Brussels was shared by a journalist on Twitter and used by news organisations, but she initially received it via WhatsApp.

#BREAKING: Two loud explosions at #Zaventem airport in #Brussels pic.twitter.com/JFw9RGLjnh

— Anna Ahronheim (@AAhronheim) March 22, 2016

Just FYI, this is NOT my video.Im not in #Brussels. It was shared with me on whatsapp.I dont have a name for credit but please DONT use mine

— Anna Ahronheim (@AAhronheim) March 22, 2016

“Was this video made available to the public?,” asked Rendle. “I don’t think we’ve got enough information here to know that.

“But if it was shared on WhatsApp and then one of the recipients tweeted it out, then there’s a good likelihood that the person who tweeted it out hasn’t authorised this video to be made available to the public.

“Then you’re crediting the wrong copyright owner and relying on video that hasn’t been made available to the public with the authority of the copyright owner. So you’re potentially in double trouble there.”

Storyful eventually tracked down the original copyright owner and licensed the video, said Sargent, but many news organisations are still crediting the person who uploaded it to Twitter, not the person who captured it in the first place.

“This comes back to the point about processes, workflow and disciplines,” said Rendle. “As it’s clear that it’s possible because Storyful have done it. The argument is that this should be part of everyday purposes for handling eyewitness video.”

Understand when crediting is appropriate, and when it is not

“The quickest way for journalists to find images to illustrate their story is to go onto social media,” said Sargent, and often news organisations will take a profile picture of an individual and credit their name and the the network on which it was found.

But in many such cases the individual did not take the photograph, so is not the copyright holder, and social networks do not hold any copyright claims over images uploaded to their platform, said Rendle.

“This practice is about as widespread as they come,” he said, “but it would be very interesting to do a study to work out how many people have asked permission to use profile pictures or other pictures on their platforms.”

There are other cases where news organisations may credit an individual for a picture or video, but without fully considering the repercussions of identifying them.

Research by Eyewitness Media Hub has documented many cases of individuals who are now forever associated with a news event because they’re names are attached to a story as a credit, whether they gave permission or not.

“There are ethical issues around crediting people who wouldn’t want to be credited,” said Rendle, “for example if it puts their safety at risk, if they witnessed something and there could be repercussions to the fact they are a witness. Then, of course, we have to think about whether it’s sensible or not to credit them.”

Getting it wrong can be very expensive

In 2010, an editor at Agence-France Presse found newsworthy photos related to the recent earthquake in Haiti on Twitter and asked the uploader for permission to use them. The images were in fact captured by professional photographer Daniel Morel, not the Twitter user who uploaded them, and Morel successfully sued for $1.2 million.

“That is a huge thing to be hanging over your head as a pictures editor,” said Rendle.

Other outlets including the Washington Post, CBS, ABC and CNN all settled claims with Morel for undisclosed amounts outside of court.

There are other such cases of mistakes by news organisations in using footage without securing copyright and suffering the legal consequences.

In another case from 2010, BuzzFeed used a picture in a list of “30 Funniest Header Faces”, in which footballers grimaced as they met the ball. One photographer issued a takedown notice, with which BuzzFeed complied, before scouring the web for every subsequent use of the image and filing a claim of $3.6 million for copyright infringement.

“I’m not suggesting he would have got that but that gives you an indication of the dollar signs that flick up in people’s eyes when this happens,” said Rendle.

The comments and examples in this article should not form the basis for any legal defense, and any questions or issues around the copyright status of an image on social media should always receive proper legal counsel.