On August 11, the same day Russian President Vladimir Putin announced that a vaccine for the coronavirus was “ready”, Kremlin Health Minister Mikhail Murashko hailed the development as “a huge contribution. . . to the victory of humankind over the novel coronavirus”.

It was a grand statement that appealed to global togetherness in the face of a global challenge. And yet, Russia’s approach to the vaccine and other treatments for the coronavirus exemplifies how some governments and populations are responding to the pandemic with the very opposite of an internationalist outlook.

In June, the United States’ bought up the entire global supply of remdesivir, which can be used to treat Covid-19, ensuring no other country had access to the drug for three months. India initially planned to release a vaccine on its Independence Day on August 15, before retracting the statement. A herbal remedy in Madagascar fuelled a wave of nationalist sentiment opposing the World Health Organization across the content.

Online discussions have often mirrored these events, particularly on the topic of a future vaccine. In some cases, national narratives have encouraged the rejection of international cooperation and been used to promote domestic agendas. In other examples, geopolitical interests and strategic national ties have fueled enthusiasm for or skepticism about specific vaccines or treatments.

On August 6, the WHO director-general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, warned of “vaccine nationalism” and what could be lost if countries failed to work together to suppress the coronavirus:

“Sharing vaccines or sharing other tools actually helps the world to recover together, and the economic recovery can be faster, and the damage from Covid-19 could be lessened.”

WHO Dir. General: 'Vaccine nationalism is not good…for the world to recover faster, it has to recover together.’ pic.twitter.com/beAmpeRxbU

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) August 9, 2020

This view is shared by experts such as Ana Santos Rutschman, an assistant professor at the St. Louis University School of Law.

“The pandemic is not a national problem, it’s not geographically contained,” she told First Draft.

“Nationalism just refers to behaviors and techniques, and often simple things [such] as contractual agreements, that allocate these public goods according to sovereign, geopolitical and geographical lines.”

Rutschman said this may pose a problem for those hoping to stop the spread of the virus, and could lead to vulnerable populations being excluded from potentially life-saving treatments.

“The first one is the public health angle: You don’t fix a pandemic by focusing on vaccine supplies to a restricted number of countries on a priority basis,” said Rutschman. “The chessboard is the entire world and policy can’t really be as skewed as nationalism would have it.”

Throughout the pandemic, our team around the world has been monitoring how geopolitics and nationalism have become sources of information disorder around cures and treatments for Covid-19. Here’s a breakdown of some of these examples.

Russia: The first vaccine?

A scientist works inside a laboratory of the Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology during the production and laboratory testing of a vaccine against the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in Moscow, Russia August 6, 2020. Picture taken August 6, 2020. The Russian Direct Investment Fund (RDIF)/Handout via REUTERS

Moscow’s rollout plan is much faster than that of other vaccine candidates. The Russian military claimed that the vaccine was “ready” in July, and that Moscow planned to vaccinate medical staff alongside the large-scale Phase III trials, according to The Moscow Times. On August 11, President Vladimir Putin announced that the country had become the first to register a coronavirus vaccine.

Russia’s long-standing relationships and interactions with other parts of the world appear to have affected the way news about its vaccine has been received. India and parts of Latin America have historical ties with Russia and in these regions the vaccine news has largely been celebrated uncritically online. Meanwhile, in Western democracies that have largely viewed Moscow through the antagonistic lens of the Cold War, there has been a greater degree of skepticism.

One of the clearest examples comes from the different responses from traditional media. Reports about Moscow’s vaccine development from Indian news organizations such as ABP News and NDTV were generally more celebratory in their tone, while US counterparts such as The New York Times and the BBC were more cautious — highlighting safety concerns around the speed of the roll-out.

The contrast is even clearer on social media, with both greater excitement about Russian progress on a vaccine and a generally celebratory tone. According to data from social media monitoring tool CrowdTangle, there were more than 1,800 posts by Indian Facebook Pages mentioning “Russia” or “Russian” and “vaccine” in the month since July 10, which were shared more than 155,000 times. Multiple text-on-image posts that have been widely shared call the development “good news.”

Even posts that indicate uncertainty over when the vaccine will be available in India are optimistic and claim that the tests have been successful, with one wishing Moscow “Good luck.” A number of Indian accounts were also tweeting about the vaccine, posting memes celebrating Russia’s announcement.

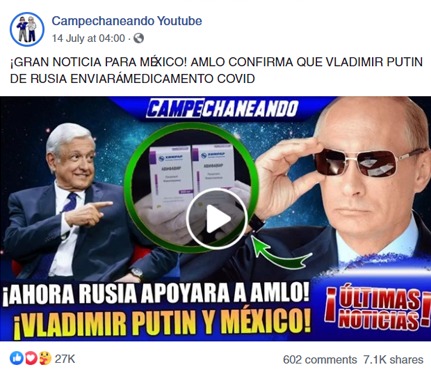

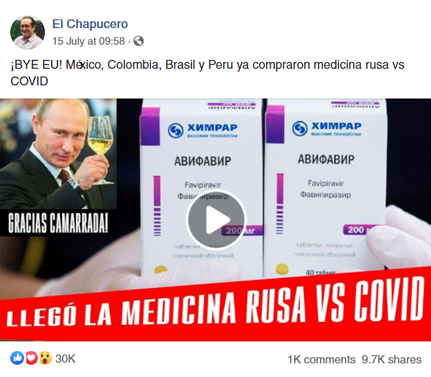

First Draft’s Laura Garcia, a journalist from Mexico, said that Moscow was actively promoting the vaccine across Central and South America before it was ready, “making sure that people in Latin America knew that they were developing a vaccine.” Russia’s promotion of its own tools to tackle the coronavirus has not been restricted to a vaccine.

On July 10, the Russian embassy in Guatemala presented a drug called Avifavir as a possible treatment for coronavirus and offered it up to Latin American countries. The medication has not yet been fully approved for treating the coronavirus, as it is in the final stages of testing, but some media outlets in Bolivia and Mexico reported that it was a “done deal” and that Latin America will be the first to benefit from Russia’s largesse.

The old Cold War dynamic influences discussions in the region, with the rush to produce and supply a vaccine being portrayed as a “new arms race between the US and Russia,” said Garcia. Given America’s failure to contain the virus, a narrative is coalescing around Russia as the “cool” agent, with Putin sweeping in to provide a solution to the pandemic.

India: ‘Messianic’ Modi

Members of All India Hindu Mahasabha offer cow urine to a caricature of the coronavirus as they attend a gaumutra (cow urine) party, which according to them helps in warding off coronavirus disease (COVID-19), in New Delhi, India March 14, 2020. REUTERS/Danish Siddiqui

Misinformation about the coronavirus has run rife in India, which has one of the largest and fastest-growing outbreaks, surpassing two million cases in early August. A consistent theme of the falsehoods, rumors, unproven treatments and conspiracy theories has been nationalism, specifically the Hindu nationalism that much of the support for the ruling BJP party is based on.

Niranjan Sahoo, a senior fellow with the Observer Research Foundation’s Governance and Politics Initiative, said Prime Minister Narendra Modi has distracted the country with nationalistic sentiments “in the middle of a pandemic when the major issue is to save lives.”

“People think that he is really in control of the pandemic management, and that everything is going fine […] even when the reality is different.”

Sahoo adds that Modi’s Hindu nationalist rhetoric, combined with his “mastery” of social media, allows him to “peddle any kind of narrative” and has emboldened individuals to spread misinformation linked to religion and nationalism.

This is evident in the discussions surrounding unproven drugs and traditional remedies that have been promoted in India during the pandemic. Traditional Indian Ayurvedic treatments and alternative remedies have always been popular, but are being extensively promoted over social media as cures for Covid-19.

In March and April, Hindu activists, including national and regional lawmakers, promoted the consumption of cow urine as a coronavirus cure, inspired by the sacred status of cows in Hinduism. Since the beginning of March, the claim has been shared widely on Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp, and has included a video of members of a religious body purportedly consuming cow urine. On Facebook alone, there have been hundreds of thousands of shares on posts mentioning variations on the words “cow urine” and “coronavirus” in public Groups and Pages, written in Hindi or English, most of which were posted in March, according to data from CrowdTangle.

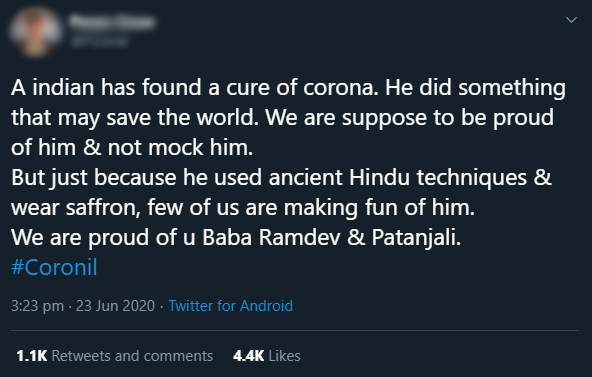

In late June, a popular yogi, Baba Ramdev, released an Ayurvedic medicine called Coronil, falsely claiming that it had a “100 per cent recovery rate within 3-7 days.” The news was widely shared on both Facebook and Twitter, and drew multiple posts of support for the treatment because it was Indian-made, such as the below tweet expressing pride at a medicine made using “Hindu techniques.”

Indian nationalism has also seeped into the promotion of modern medical interventions to halt the coronavirus. In early July, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), the body responsible for the country’s response to the pandemic, claimed that India’s coronavirus vaccine candidate would be released by August 15 — India’s Independence Day — in a move that Sahoo said was a “mix of populism and vaccine nationalism.” The statement was later retracted by the ICMR after several doctors and professionals questioned the deadline, with The Wire reporting that it gave Modi “an opportunity to win political points.”

Most recently, multiple lawmakers, including former union cabinet ministers such as Jaskaur Meena and Arjun Ram Meghwal, and members of parliament such as Pragya Thakur, have claimed that the coronavirus would disappear once a controversial temple to the Hindu deity Lord Ram was constructed. The temple, built on the site of a mosque that was destroyed by a mob in 1992, is a powerful symbol of the Hindu-nationalist message promoted by Modi.

Madagascar: Organic remedies

FILE PHOTO: Madagascar’s President Andry Rajoelina and his wife Mialy at Iavoloha Palace in Antananarivo, Madagascar September 7, 2019. REUTERS/Yara Nardi/File Photo

In April this year, Andry Rajoelina, the president of Madagascar, promoted an unproven treatment that he claimed would kill the coronavirus. The herbal concoction, called Covid-Organics, is produced from a plant called artemisia that has antimalarial properties.

Rajoelina’s tweet announcing the launch of the drink on April 20 was widely viewed and shared, spurring a months-long online conversation about the product. His later tweets, which included images of himself alongside the leaders of Senegal and Guinea-Bissau, included statements such as “Long live Africa and long live its natural wealth!” and “It’s a united Africa which fights #Covid-19!” Dozens of accounts expressed their pride at an African-made remedy in the comments, and asked others to believe in a cure that had been developed on the continent.

A number of countries in Africa expressed their interest in the beverage, while the WHO urged caution. In an interview with France 24, Rajoelina claimed that the WHO doubted the remedy because it was made in Africa. “I think the problem is that [the drink] comes from Africa and they can’t admit … that a country like Madagascar … has come up with this formula to save the world,” he said.

This statement was soon used to create a fabricated quote suggesting that Madagascar was leaving the WHO, and that Rajoelina had encouraged other African countries to follow suit. Hundreds of Facebook posts repeated the false claim, including some verified accounts, generating thousands of interactions.

“The regime believed that it could surf on this new African pride acquired by Malagasies, by presenting this artemisia-based product, Covid-Organics, and hoping to solve the global problem that is the coronavirus pandemic,” Tsiresena Manjakahery, Agence France Presse’s correspondent in Madagascar, told First Draft.

Sociologist Marcel Razafimahatratra has told AFP that Covid-Organics created only “serious illusions” that could prolong the pandemic, and divided the medical community, and even worse, the country.

“It only further strengthens the cult of personality [around the president], that will neither bring a solution to the fight against Covid-19 nor ‘solve’ the current economic problems and above all, will have an impact on political life in the near future,” said Razafimahatratra.

United Kingdom: Brexit divisions

A woman walks past a closed shop covered in social distancing signs following the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in Chester, Britain, August 10, 2020. REUTERS/Phil Noble

The decision to leave the European Union continues to be one of the key fault lines in the UK, and it permeates many online conversations around the pandemic, the topic of a vaccine against the coronavirus included.

Reports that the UK had opted out of the EU vaccine program in July gained widespread traction in online “Remainer” communities that support staying in the EU, fueled by criticism of Brexit and the government. Actor David Schneider, a prominent pro-EU voice, pointed to other recent decisions made by the British government not to participate in EU schemes, including one for PPE procurement, calling Brexit a “suicide cult.”

Yet the news also led to the expression of nationalist sentiment from pro-Brexit sources, with some claiming the UK would develop its own vaccine first and celebrating the development. Leave.EU, the campaign pushing for the UK to leave the EU during the referendum, claimed on its Facebook Page that “Remainers are trotting out that same tired old propaganda — better to be enslaved than emancipated.”

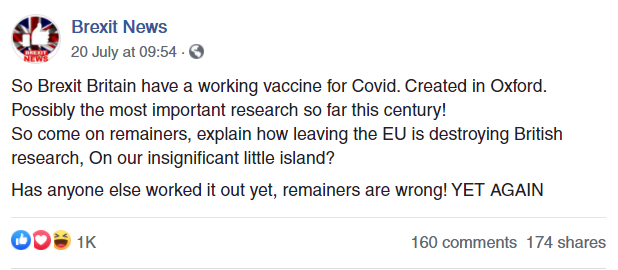

The early positive results of the Oxford trial released July 20 further fueled nationalist narratives. A tweet from anonymous pro-Conservative Party and pro-Brexit Twitter figure “Mason Mills” claimed: “There’s a reason we are called GREAT Britain” while Facebook Page “Brexit News” used the news to crow:

“So Brexit Britain have [sic] a working vaccine for Covid. Created in Oxford.

“Possibly the most important research so far this century!

“So come on remainers, explain how leaving the EU is destroying British research, On our insignificant little island?

“Has anyone else worked it out yet, remainers are wrong! YET AGAIN”

Likewise, “The Bruges Group,” a pro-Brexit think tank, pointed to the development to say: “We are so much better off out [of the EU].”

Britain is set to leave the European Union at the end of 2020 and, with no trade deal currently in sight, there is a question mark over future deals for buying and selling goods and services — including vaccines.

Nationalist responses to a global problem

The symbolism of being the first country to develop an effective medical solution to the pandemic cannot be understated and with such a huge boost to reputation on the line, it is perhaps not surprising that each national victory on that path — real or imagined — generates a fevered response.

The many thousands of responses to each new development, filtered through national politics and geopolitical concerns, demonstrate the strength of this interplay among politicians, governments and the public. Nationalistic narratives are meant to elicit an emotional response, to encourage people to rally around the flag regardless of the circumstances. In many cases, it is working.

Indian Prime Minister Modi’s messaging, for example, has helped drive his “messianic” popularity. His approval rating was at 74 per cent at the end of June — the highest of any democratically elected leader — according to a Morning Consult poll, despite the alarming rise of coronavirus cases in the country at the time. When leaders can juice their popularity by shaping medical responses to the pandemic to fit their own agenda, decision making will often be led by politics more than science.

That focus on national responses to what is a global problem, influenced by shifting goals, alliances and animosities, could hamper our ability to recover from the pandemic.

As the WHO’s Tedros warned, mitigating the worst effects of a disease being felt across the world requires international cooperation. “For the world to recover faster, it has to recover together.”

This article is part of a series tracking the infodemic of coronavirus misinformation.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.