By Jaime Longoria, Daniel Acosta Ramos and Madelyn Webb

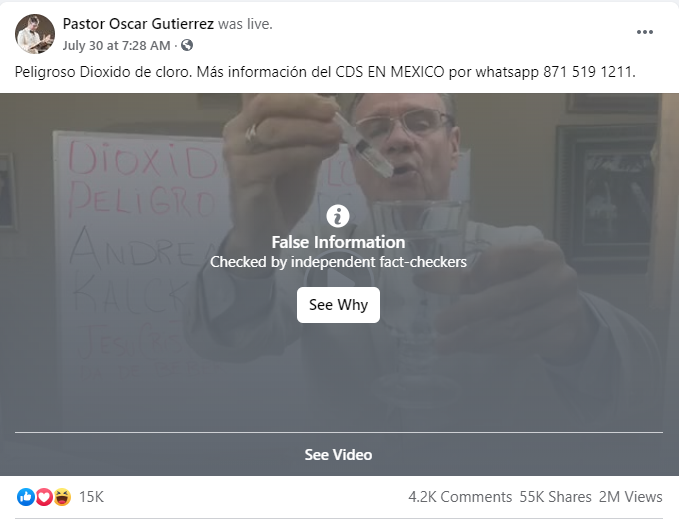

On July 30, a Mexican pastor named Oscar Gutierrez broadcast what would become one of the most-watched videos on Facebook about chlorine dioxide solution, an industrial bleach he promotes as a cure and preventive treatment for Covid-19.

“Chlorine dioxide is dangerous — but for whom? For the pharmaceutical companies and corrupt governments,” said Gutierrez in the broadcast on his Facebook Page “Pastor Oscar Gutierrez,” which has almost 220,000 followers. He is also a participant in Facebook’s Stars program, which allows content producers to receive payment directly from their audience, which means Gutierrez’s videos and live broadcasts have ostensibly been evaluated and approved via Facebook’s Community Standards. Each ”star” received translates to $0.01 in revenue going directly to the creator.

Gutierrez went on to claim the solution, known as CDS or “miracle mineral solution” (MMS), is being suppressed so that microchips could be introduced via a vaccine to control people’s DNA. “At least try it because you won’t die,” Gutierrez said later in the video. It has been viewed more than 2 million times and marked by Facebook as false information.

Harmful misinformation about the coronavirus abounds in Latin American Christian communities, with figures such as Gutierrez pushing unproven and potentially dangerous treatments and capitalizing on fear to promote anti-vaccine sentiment. The trusted position of these religious leaders can legitimize potentially dangerous ideas for a large audience via independent Christian news networks and social media.

Read more: The psychology of misinformation: Why it’s so hard to correct

“A religious leader has a relationship of power where the truth that they transmit is one that, be it about a political or moral decision, is delivered from a position of ascendency,” said Nicolás Iglesias Schneider, coordinator of GEMRIP, an organization focused on the public role of faith and religion.

“When a leader has a truth that is immutable, it is a truth that is unquestionable because it is endorsed by a deity or is a word sent by God,” said Iglesias. “For the religious faithful in the context of a pandemic where there is less opportunity to check with neighbors and family and where there is less social interaction, people are more vulnerable and are likely to become more radicalized.”

The post labeled as “False Information” by Facebook has more than 2 million views. Screenshot by author.

Latin American Christian communities aren’t the only religious groups to fall victim to misleading claims or outright misinformation about the pandemic. In June, Spanish cardinal Antonio Cañizares Llovera declared attempts to find a vaccine the “work of the devil” that would involve “aborted fetuses” in a filmed Mass shared around the world. Church leaders in Australia raised similar concerns recently, apparently unaware that the practice of using cell lines grown from a fetus in 1972 has been commonplace in vaccine development for decades.

In India, Hindu religious and political leaders have promoted cow urine as a cure for Covid-19, inspired by the sacred status of cows in Hinduism, and declared the coronavirus would leave India once a controversial temple was completed. Claims that a polio vaccine contained pork products or toxic ingredients, often circulated by Muslim clerics, have damaged the fight against the disease in Muslim-majority Pakistan.

But it is the diversity of coronavirus misinformation in Latin America, its potential for real-world harm and its connection with the Latinx diaspora throughout the United States that make it such a cause for concern.

Magic beans and consecrated oil

Several prominent religious figures have marketed unproven treatments and cures, a common misinformation trope even before the coronavirus pandemic. So-called “snake oil” remedies are so common in part because they often produce a profit, and those hawked in Latin American Christian communities are no exception.

Valdemiro Santiago, an evangelical pastor who leads the Universal Church of God’s Power, is being investigated by the Federal Public Prosecutor of Brazil for selling beans that he claimed cured coronavirus for 1,000 Brazilian real each (about $180). In a YouTube video, he claimed that a medical report had detailed the recovery of a terminally ill patient thanks to the beans.

Similarly, Sílvio Ribeiro, pastor of Catedral Global do Espírito Santo in Porto Alegre in Brazil, is being investigated by Porto Alegre police under suspicion of “charlatanism,” according to Police Delegate Laura Lopes. On March 1, he held a live event that was advertised and broadcast across social media. The flyer for the ceremony read, “Come because there will be anointing with consecrated oil … to immunize against any epidemic, virus or disease!”

Em Porto Alegre, a igreja anunciou um culto chamado “O Poder de Deus contra o Coronavírus” em que prometia imunização por meio de um “óleo consagrado” https://t.co/uU7EGwwO4r

— BBC News Brasil (@bbcbrasil) March 2, 2020

“Faced with illness and the possibility of death, it is common for human beings to feel hopeless and helpless,” Angela Rotunno, coordinator of the Operational Support Center for the Defense of Human Rights, told the newspaper Estadão. This emotional fragility drives away rationality and, as a consequence, makes it easy to believe in any promise of protection or cure. It is what is happening at the moment. Unscrupulous people try to take advantage of this discouragement.”

The Mexican pastor Gutierrez has in turn popularized the work of Andreas Kalcker, a notorious anti-vaccination advocate who claims to be a German scientist and has been a proponent of CDS as a treatment for Covid-19 in Latin America. The bottles of CDS that the pastor promotes on his Facebook broadcasts are labeled with Kalcker’s name and the Bible verse John 10:10, in which Jesus says he provides his flock life and abundance.

❌Cuidado con el vídeo que afirma que el CDS o dióxido de cloro (derivado del MMS) cura el coronavirus: no hay ninguna prueba y puede ser peligroso #CoronavirusFacts https://t.co/9dFWIfccsR

— MALDITA CIENCIA (@maldita_ciencia) April 6, 2020

Platform of the Antichrist

Beyond phony and potentially dangerous cures, misinformation narratives and conspiracy theories found in global anti-vaccine communities have been adopted enthusiastically by some religious figures in Latin American communities.

For GEMRIP coordinator Iglesias, this demonstrates the boundlessness of misinformation and its ability to transcend national borders. “There is almost nothing that is strictly from Uruguay or Argentina or the Southern Cone,” he said, “because in reality these all-encompassing narratives, including conspiracy narratives, have become so widespread.”

Pastor couple Miguel and María Paula Arrázola, directors of Iglesia Ríos De Vida in Cartagena, Colombia, shared a May 6 live broadcast with their 394,000 Instagram followers on Miguel’s account where their guest Ruddy Gracia, another evangelical pastor, said that “behind the compulsory vaccine there is a chip called ID2020 made by Bill Gates.” The aim, according to Gracia, would be to create a global registry of all those who have been inoculated, registering them via the microchip. “That is the beginning of the platform of the Antichrist, how he will bring about the mark of 666 and will result in you not being able to get a passport, travel, have a license, buy or sell without that chip.” María Paula agrees, saying that is the reason she would refuse vaccination. Gates has become a conspiracy theorist dog whistle, often invoked to promote anti-vaccine narratives.

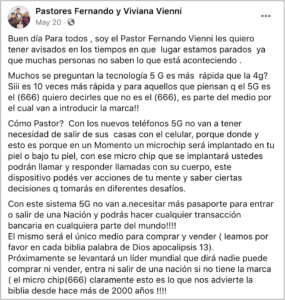

The Facebook page for Pastor Vienni claimed “a world leader will rise that will say no one can buy or sell, enter or leave a nation if it doesn’t have the mark (the micro chip (666)”. Screenshot by author.

Another example came later that month when Argentine pastors Fernando and Viviana Vienni shared a post calling for opposition to the vaccine, which they claimed is a vehicle for a secret implant originating from supposed Freemasons such as Gates. “They have created a sickness (coronavirus) and via this virus they will say they found the solution!!!” they wrote. “The coronavirus, the microchip (5G) and the vaccine is all a test of the end times!!!!! We are already in those times!!!”

The ID2020 conspiracy theory cited by some religious figures is a common thread among the more extreme elements of the anti-vaccination community. These conspiracy theories have spread among online communities, adapted to new audiences and combined with other narratives.

Throughout May and June, the same text combining many of these conspiracy theories was copied and pasted in thousands of public posts across Facebook, including the claim that Catholicism would be replaced by a new Satanic religion called “El Crislam.”

The Facebook Page that received the most interactions for its post on the subject bore the name of Yiye Ávila, an influential Puerto Rican televangelist and author known for preaching about the apocalypse. Ávila died in 2013. It is not clear whether the page is official, but it has almost 500,000 followers.

Ávila’s grandson, Miguel Sánchez-Ávila, appears to have followed in his grandfather’s footsteps. A large Facebook page and smaller YouTube channel featuring Miguel promote similarly apocalyptic posts and videos.

“Any conspiracy theory, be it about the origin or solution to the coronavirus, espoused by a powerful charismatic religious actor becomes a very strong truth for the individual who receives it,” said Iglesias. “They incorporated it to their belief system in a much less critical way.”

People in despair

A misleading Covid-19 narrative unique to religious communities, though certainly not unique to Latin American Christian communities, is the emphasis on worship center closures because of the virus. Church leaders decry the shutting of places of worship, citing various other facilities allowed to remain open, and bemoan their “nonessential” status. Though pushback from religious figures eager to reopen does not usually contain misinformation as such, it contributes to the belief that the virus is less dangerous than we are being told.

In an interview in São Paulo newspaper Estadão, Pentecostal pastor Silas Malafaia expressed his frustration with the closures, saying: “Are people going to die of the coronavirus? Yes. But if there is social chaos, much more will die. Churches are essential to assist people in despair, anguished, depressed, who will not be attended to in hospitals.”

Churches around the world have been blamed for contributing to increased transmission of the virus, yet religious leaders continue to promote the idea that church gatherings are not dangerous, or that the risk is worth it, as Malafaia implied. Other religious groups have challenged local authorities’ orders by holding clandestine services.

On July 12, an evangelical pastor was arrested in the Chilean province of Arica for holding religious services in an open space with more than 50 people present. In April, Claudia Pizarro, mayor of La Pintana commune south of Santiago de Chile, closed the “Impacto de Dios” church after its pastor, Ricardo Cid, carried out daily services with 30 to 50 people.

“These are irresponsible attitudes not only of the pastor but of all those who participated,” Pizarro said after the incident. “It is a lack of culture, of criteria, an irresponsibility that this continues to happen.”

Refusal to take the virus as a serious threat, particularly when that refusal comes from a person with influence, is itself a form of dangerous misinformation. When Cid was asked to take a Covid-19 test, he refused. “I don’t have it, because I know I don’t,” he said. “My God would never allow it. Jesus never became infected, even from leprosy.”

The role of the Christian media

Misinformation spreading in Latin American Christian communities has the benefit of an independent Christian media that can amplify narratives that may not be published in other press.

CBN Latino, the Spanish-language branch of the massively popular Christian Broadcasting Network with regional branches in Mexico, Guatemala and Costa Rica, has more than 94,000 followers on Facebook and a WhatsApp call line. “Club 700 Hoy,” the Spanish-language version of “The 700 Club,” CBN’s most popular program, has over 193,000 Facebook followers.

Though CBN’s eponymous outlet rarely publishes outright false information, “The 700 Club” has a history of promoting conspiracy theories and misinformation. CBN’s other properties often provide space for people to express skepticism about certain scientifically supported topics such as climate change or evolution.

Christian outlets work in tandem with religious leaders, retweeting and sharing one another’s content to maintain a media ecosystem editorially independent from the secular press that might otherwise weed out misinformation narratives.

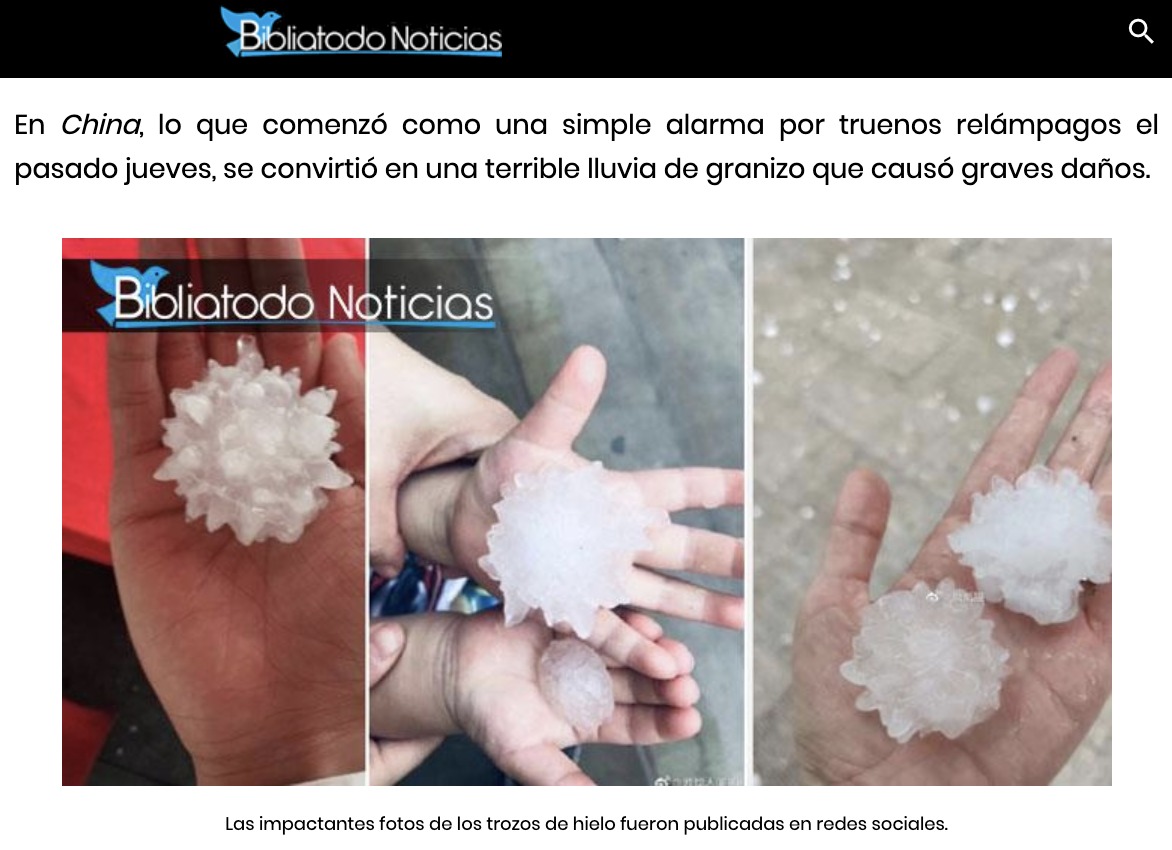

In late June, the Spanish-language Christian outlet Bibliatodo published a story about a hailstorm in China where the ice was supposedly shaped like the coronavirus. Though there is no evidence the photo of the oddly shaped hail is fake, the article cites Israel Breaking News connecting the hailstorm to the end times and quoting a rabbi claiming the storm was godly intervention.

The website Bibliatodo Noticias reported that hailstones allegedly in the shape of the coronavirus were and related it to the “seventh plague” in the Bible. Screenshot by author.

The pandemic has also pushed religious groups to experiment with various forms of mass communication. It is no longer exclusively the neo-Pentecostals and fundamentalists who have taken to broadcasting their services live to audiences outside their communities.

Iglesias notes that an increase in the reliance on social media, including the use of streaming, Zoom and YouTube during the pandemic, has broadened the reach of religious messaging. “Because of this, religious speech and its political impact are no longer limited only to the temple and a direct audience,” he said. And these religious figures have amassed large online followings, some with incredible speed.

In Colombia, Miguel Arrázola, pastor of the Ríos De Vida church, increased his Facebook page interactions by 233 per cent from the last week of February to the last week of March, according to data from Facebook-owned social monitoring tool CrowdTangle, coinciding with the announcement of lockdown measures.

Gutierrez, the Mexican pastor, created his Facebook page on May 7, in the midst of the pandemic. In just three months, he attracted more than 219,000 followers. His most popular video promoting chlorine dioxide has reached some 2.2 million views and 57,000 shares, drawing so much attention that Facebook labeled the post as false information. In total, Gutierrez’s videos have been viewed around 10 million times.

Community outreach

Previous research has shown that the proliferation of religious-based misinformation is not limited to Latin American Christian communities. Religious communities of all types are susceptible to misinformation, and public health outreach in faith communities is an important factor in addressing the pandemic.

For Iglesias, the need to provide science-based information and teach critical thinking is paramount. Still, the challenge comes with confronting misinformation among a distressed population where individuals are more likely to cling to faith, a substance or a religion.

“I think what is important is to prioritize information that is scientifically validated,” Iglesias said. “And to that end, civil society … can promote the responsible use of information.”

The real world consequences of this form of false information have recently been highlighted by two poisonings and two reported deaths in Argentina from CDS, despite its proponents, such as Pastor Gutierrez, insisting it is safe.

Juan Andrés Ríos, 51, died August 11 after ingesting a liter and a half of the prepared solution in two days in an attempt to treat symptoms that were reportedly similar to those of Covid-19.

“My brother didn’t know whether or not he had coronavirus, but he had symptoms,” said Ríos’s sister in an interview with Radio10. “In the desperation to cure himself, he drank chlorine dioxide. No one forced him to do so, but he made that decision after watching a video that said it cured coronavirus.” Ríos bought the CDS via Facebook, according to his sister.

Another death occurred August 15, when a 5-year-old was brought to a hospital without vital signs after his parents had administered a “preventative” dose of CDS. The child died of multiple organ failure, resulting in an investigation by the Neuquén prosecutor’s office.

While religious communities provide a dangerous vector for misinformation, they also present an opportunity to combat it. Addressing misinformation emanating from Christian sources in Latin America could ripple throughout the communities their congregations come from. When that misinformation is potentially so dangerous, working to inoculate populations against it is more necessary than ever.

This article is part of a series tracking the infodemic of coronavirus misinformation.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.