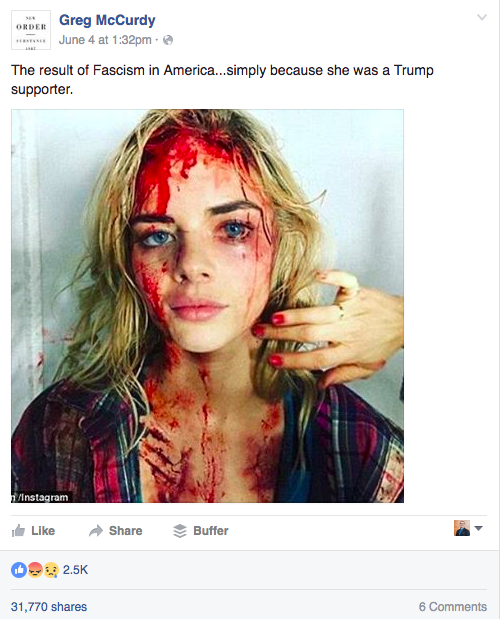

In early June, a man posted an image on Facebook of a bloodied woman who he said was attacked at a Trump rally because she supported his candidacy. “The result of Fascism in America,” wrote Greg McCurdy.

It’s been shared more than 30,000 time from his profile, and also spread to Twitter. The woman in the photo is Australian actress Samara Weaving, and it shows her in makeup for a scene in the Starz series Ash vs Evil Dead. She posted the image to her Instagram account months ago.

As the US presidential election moves toward the conventions and a November vote, we can expect to see more online political hoaxes. Supporters of Trump and Hillary Clinton are deeply divided along partisan lines. The more people that are polarized in their beliefs, the more they’re willing to believe and share something that attacks the other side, regardless of whether it’s true.

A general rule for political hoaxes during election season is that they will be tied to to current events, ongoing scandals, and the perceptions and actions of key politicians and their campaigns. These hoaxes are typically engineered to appeal to partisans on one side or another, and they do so by reinforcing existing beliefs and perceptions.

The case of the fake bloodied Trump protestor is a good example. There have been flashes of violence inside and outside Trump rallies, but Trump’s supporters feel their side has been unfairly portrayed as the instigators. The story of a beautiful Trump supporter being bloodied by left-leaning protestors is the perfectly shareable counter narrative.

All the stories below are fake, and there will be more. Here’s a look at the types of US political hoaxes we’ve seen so far. For tips on how to spot an online hoax, see this previous First Draft article.

Check out US Elections: Make your social monitoring great again for tips on campaign coverage

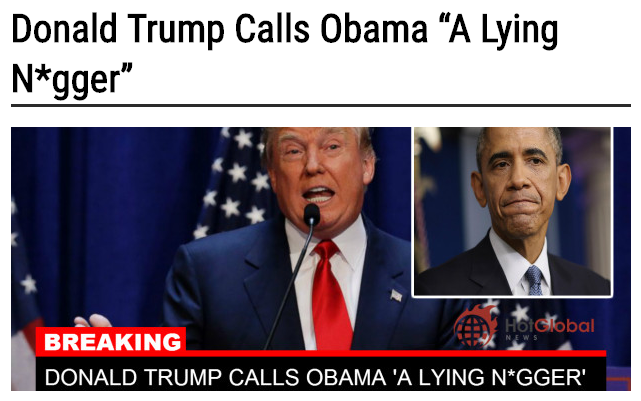

1. Fake quotes from candidates

A simple way to verify notable quotes is to copy and paste the key language, keep it in quotation marks, and search on Google and Twitter. If a candidate really said something newsworthy, it will have been reported and tweeted almost instantly.

If the quote turns out to be from a single source that you’ve never heard of you need to evaluate that source’s credibility by checking out what or who it is — and why no one else is following its report.

http://christiantimesnewspaper.com/hillary-clinton-blames-racism-for-cincinnati-gorillas-death/

2. Fake campaign ads and websites

If the supposed ad is an image, perform a reverse image search to see where else it exists online. As with quotes, see who else is reporting on the ad. New campaign ads are often promoted to media by the campaigns, so they will be covered quickly by credible outlets. When in doubt, always contact the campaign before covering. Ads from political action committees (PACs) or other third parties that are unaffiliated with the campaigns should also be traceable back to an official organization.

For verifying websites, the first step is always to run a WhoIs search to see when the domain was registered, and to see who owns it. Beware of websites that were recently registered or that conceal their ownership information, as official campaigns and entities will be clear about ownership details. As always, reaching out to confirm the ownership of a website is an important step.

https://twitter.com/charlescwcooke/status/735809898383081472

3. Fake Hillary Clinton corruption/email scandal reports

The Clinton email story is being covered closely by many major media outlets, as is the Benghazi story. Any big developments will likely come from credible outlets and will be widely reported within a short amount of time.

As with quotes, Google to see who else is reporting the information, and to determine which source it came from. Read the About page and run a Whois for any unfamiliar websites.

http://www.satiratribune.com/2016/03/28/fbi-charges-clinton-unlawful-e-mail-removal-national-security-information/

4. Fake violence by supporters

These fake reports can often be debunked thanks to a quick reverse image search on any photos of violence, or by evaluating the source of a report through its About pages, a WhoIs search, and by seeing if anyone else is reporting the information.

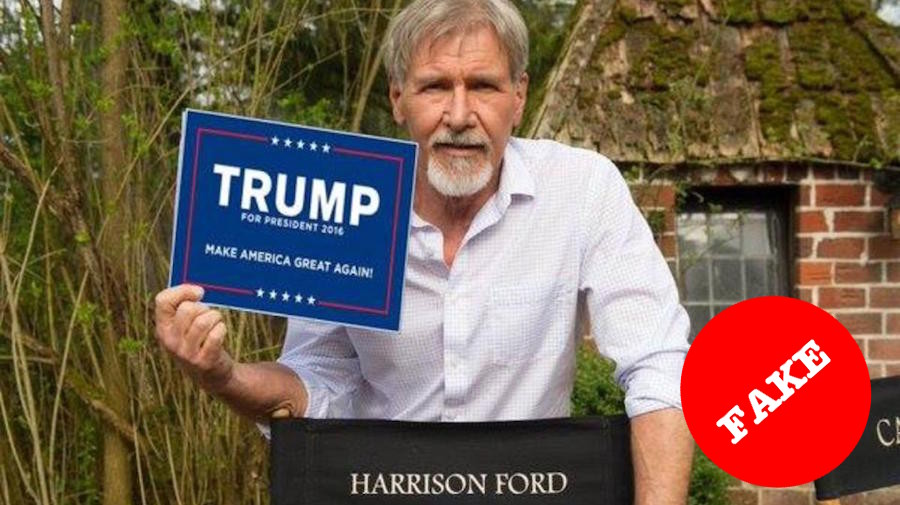

5. Fake endorsements

These often originate on hoax websites, so evaluate the source and see if credible outlets also have this news. If the endorsement consists of a single image, as with the Harrison Ford example below, perform a reverse image search and also see if there is a photo credit or sourcing information offered to explain where the image came from.

http://www.satiratribune.com/2016/01/20/trump-paid-sarah-palin-10-million-for-endorsement/

6. Fake campaign promises

Campaign promises usually come directly from the candidate themselves in the form of speeches or media interviews. If you can’t find a credible outlet reporting it, then it could very well be fake. Also, beware of major promises or policy proposals that come from websites that are not the official campaign site.

https://adobochronicles.com/2015/09/03/puerto-ricans-chamorros-others-will-lose-citizenship-under-trump-presidency/

http://www.burrardstreetjournal.com/donald-trump-admits-renaming-new-mexico-will-be-his-first-act-as-president/?fb_comment_id=1103545423009378_1105040092859911

7. Fake Obama campaign interventions

Anything the president says or does is widely covered. Follow the previously offered advice about searching to find the original source, and reverse image search any photos.

Follow First Draft on Twitter and Facebook to get the latest reads and resources about fake news, verification and social newsgathering.