As journalists, reporting accurate information and avoiding the spread of rumor and misinformation are fundamental to our mission.

Research shows, however, that fighting misinformation online isn’t just about what we communicate to readers, but also very much about how we communicate with readers. Faced with the challenge of fake news spreadings faster and wider than corrective debunks, we need to think hard about how to tell fact-based stories that are as viral and shareable as the fakes.

At the recent RightsCon, members of the Meedan and Amnesty International teams got together to tackle this challenge head-on. Inspired in part by the sticker-loving culture of media and technology conferences, we wanted to get people thinking about the risks of participatory misinformation and how we could design eye-catching stickers to encourage informed sharing of more truthful media.

Meedan’s Chris Blow introduces the design challenge at RightsCon. Image: An Xioa Mina/Meedan

After two days of solid conferencing and panel discussions, we wanted to get people’s creative juices flowing with an energetic and fast-paced design sprint. We set our participants a timed challenge based on a light-hearted scenario: There’s been a jailbreak at the San Francisco zoo, and animals are on the loose. Photos are emerging all over social media, some of which are true but many of which are false. Participants had 30 minutes to work in groups to provide eye-catching, shareable Twitter cards that debunked fake images being shared or made real images more shareable.

While we chose a mildly ‘fun’ topic on which to focus our design energies, with the help of Christoph Koettl, the founder and editor of Amnesty International’s Citizen Evidence Lab, and Chris Blow, a designer at Meedan, we grounded the exercise in the serious issues of misinformation in human rights and disaster relief contexts: settings in which online rumor can have dangerous offline consequences.

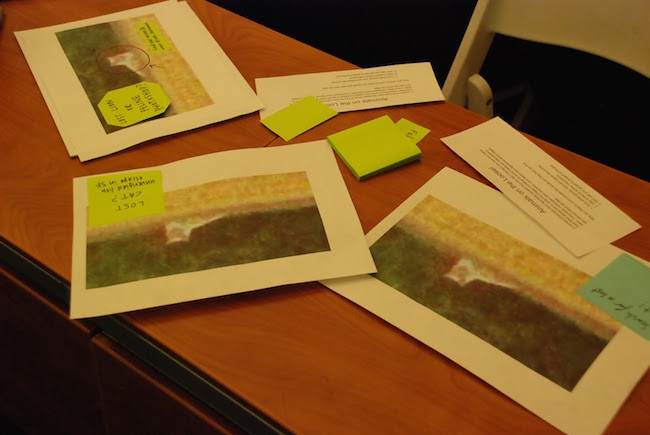

Newsroom sleuths were assigned a photo, along with a prompt detailing the veracity of the image and information about how it had been verified or debunked. Sticky notes, scissors, and markers were provided, and we got to work.

Designs courtesy of RightsCon participants. Image: Chris Blow/Meedan

Four things we learned

1. There are many different ways to engage with audiences through stickers

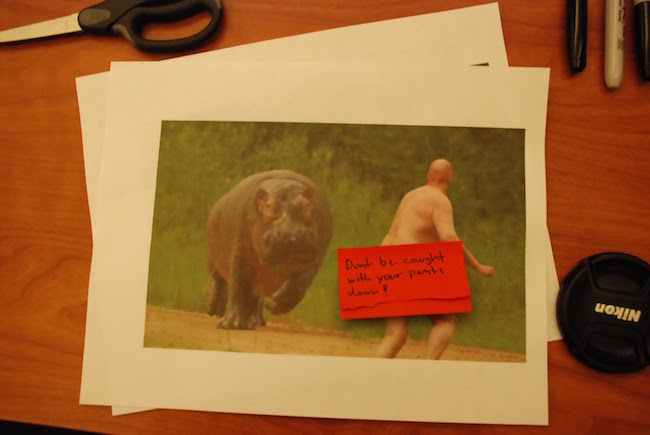

Different groups of participants took different approaches, all of which were well-considered for the scenario. One group took a humorous direction, placing a bold red sticker over an eye-catching part of an image. The sticker sought to play on audience fears about how friends might perceive you if you share fake content, taking the form of a GIF flicking between “Don’t get caught with your pants down” and “Don’t share fake photos”.

In his research into the spread of fake content, Craig Silverman found humor to be a particularly effective strategy for countering misinformation.

Designs courtesy of RightsCon participants. Image: Chris Blow/Meedan

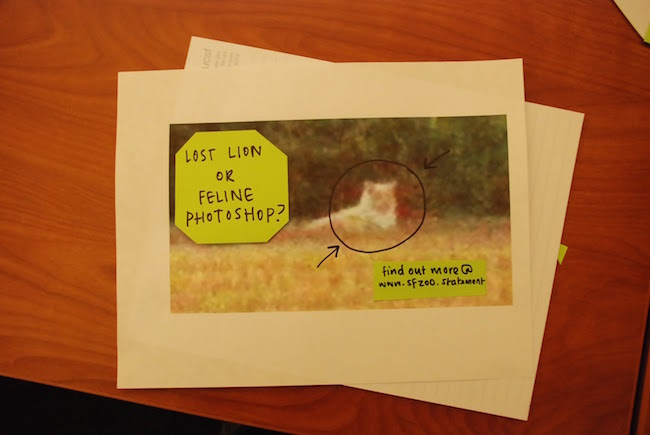

Another group took a different approach, playing on the conventional “Lost Cat” poster to flag a lack of certainty about a reported lion sighting. Given the uncertainty around the veracity of the photo, this group also included a link, suggesting that people who saw the stickered image could check the link for the latest information.

Designs courtesy of RightsCon participants. Image: Chris Blow/Meedan

Other participants played with stickers that censored parts of the image, used stickers to make ‘spot the difference’-style games, and puns – all creative responses to the brief that show the range of strategies newsrooms and rights reporters could deploy.

2. Context is king

What was so great about the various responses by participants was that they were all very well adapted to the prompts, both in tone and design. There’s a challenge here, however: is it possible to scale an approach to visual design around debunks, or will the most effective debunks be fully custom-made for a given context? One suggestion that emerged from the session was a somewhat extensive sticker library, coupled with basic training for journalists in visual debunk design.

3. We need better tools for preparing these visual assets

As much as we think about tools and techniques for social newsgathering and verification, to date there have been few tools that focus on preparing the outputs of these processes for publication or broadcast.

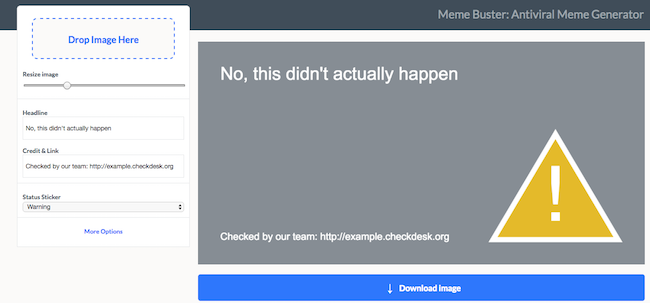

Our prototype Memebuster (working title) is one such tool. It’s still an experiment at present but is open source and – we hope – a step on the path to finding an effective design solution for debunking misinformation. We’d love your feedback.

Add text and different warning ‘stickers’ to images with Meedan’s Memebuster

4. Take an audience perspective

Thinking through how to design for this context reveals a lot about what information is most important to communicate to audiences – what do they need to see in the fraction of a second that they’re scrolling through their Twitter feed – and what risks exist if we don’t think carefully about the design aspect of verification. Take this example, from the excellent team at Politifact in 2014:

While the text of the tweet explains this is a debunk, the fake image itself is shared as-is, risking potential recirculation stripped of the crucial context provided by the tweet.

Stopping the flood of misinformation on social media and the broader internet will take more than a three-day conference, likely involving an active effort from journalists, news organisations, platforms and the audience themselves. But experiments and collaborations drive progress and we’ll need to work together in similar ways – as an industry – to find a solution.

Check out ‘Antiviral social media: How can newsroom designers make debunks better?‘ and other reads in our Fakes and Hoaxes section