Recent scandals about the role of social media in key political events in the US, UK and other European countries over the past couple of years have underscored the need to understand the interactions between digital platforms, misleading information and propaganda, and their influence on collective life in democracies.

In response to this, the Public Data Lab and First Draft collaborated last year to develop a free, open-access guide to help students, journalists and researchers investigate misleading and viral content, memes and trolling practices online.

Released today, the five chapters of the guide describe a series of research protocols or “recipes” that can be used to trace trolling practices, the ways false viral news and memes circulate online, and the commercial underpinnings of problematic content. Each recipe provides an accessible overview of the key steps, methods, techniques and datasets used.

The guide will be most useful to digitally savvy and social media literate students, journalists and researchers. However, the recipes range from easy formulae that can be executed without much technical knowledge other than a working understanding of tools such as BuzzSumo and the CrowdTangle browser extension, to ones that draw on more advanced computational techniques. Where possible, we try to offer the recipes in both variants.

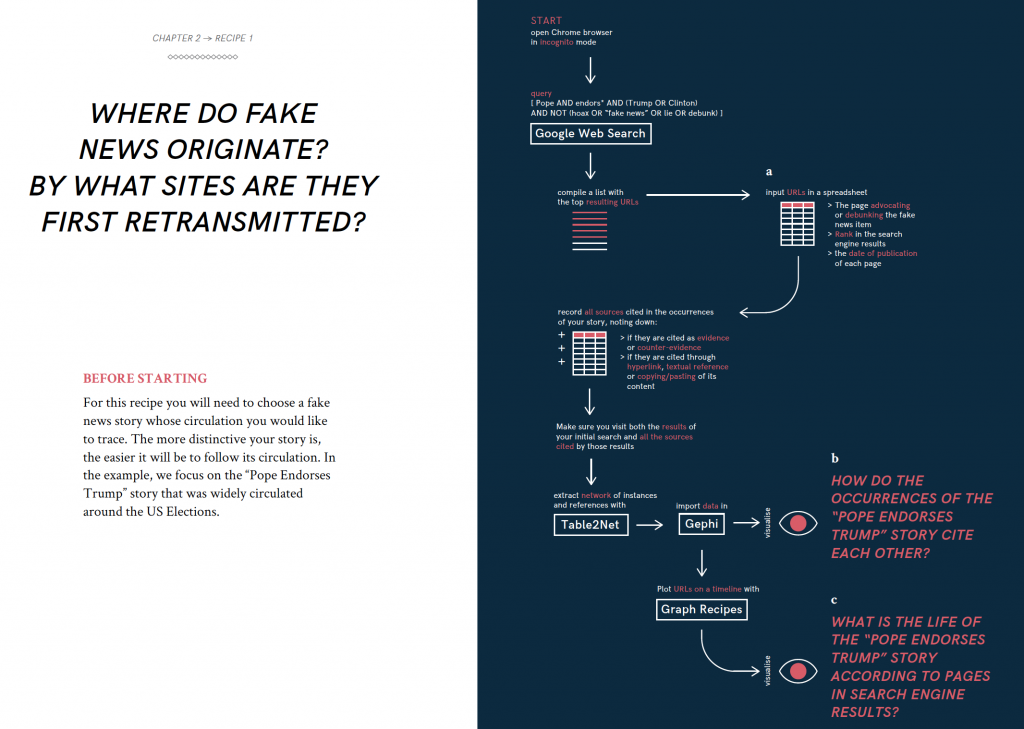

To facilitate the navigation of recipes we also provide protocol diagrams for each analysis, which represent the key methodological and analytical steps that need to be taken to arrive at the provided results.

A recipe describing how generate a citation network of articles discussing a particular claim

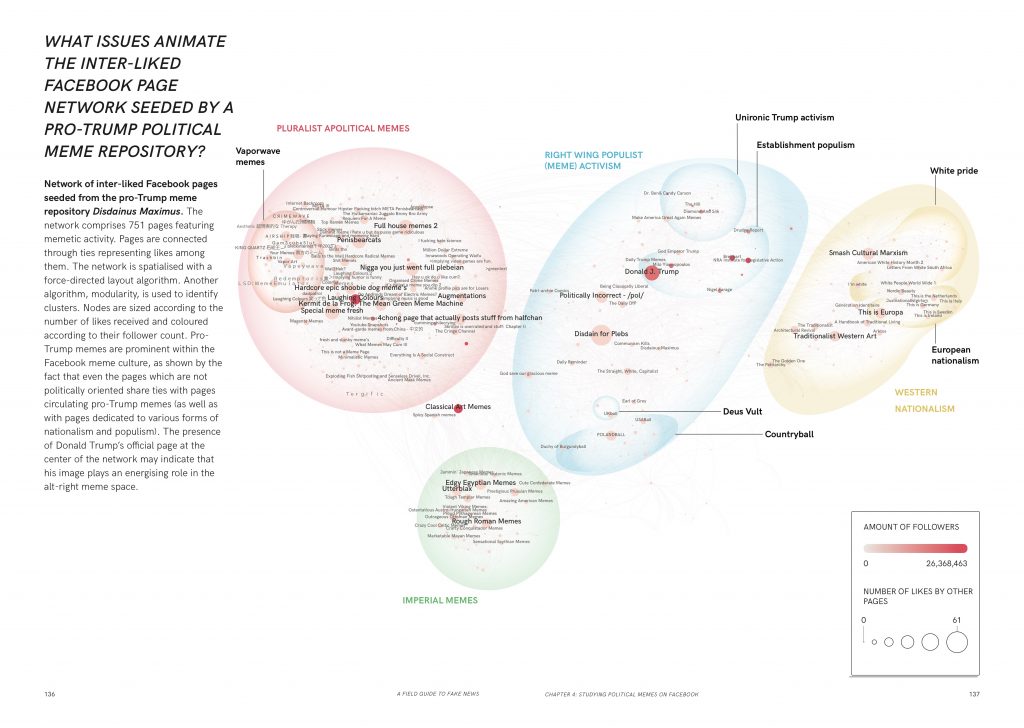

As readers will notice, the research protocols that we describe focus on capturing how digital platforms shape contemporary forms of misleading information (textual, visual or multimodal) as they travel across the web and social media. They are essentially techniques for enhancing the analysis of textual and visual content using methods that account for the networked character of the platforms on which they travel. This includes exploring the user networks where content is embedded, the citation and hyperlink networks created between websites circulating this content, and the web tracking services associated with websites.

A visualization of a network of interlinked Facebook pages, seed from the pro-Trump meme repository

For this reason, the research methods we outline can be used to investigate not only manipulative content online, but any content that circulates on digital platforms. For example, these methods can easily be used to better understand how mainstream news content circulates online. Hence, it may be a handy resource for new media, digital culture and digital journalism courses and trainings.

While in 2016 many used the term “fake news” to refer to false viral content shared on digital platforms, in 2017 it was increasingly adopted by politicians around the world as a threat, an insult and a weapon against journalists and media organisations. As a result, several commentators (including our colleagues at First Draft) have advocated a shift away from the term “fake news” to an array of more specific terms such as mis-, dis- and malinformation, grouped under a new umbrella term “information disorder”. We have updated the title of the guide to reflect and recognise this work.

Nevertheless, we have chosen not to abandon the phrase “fake news”. We retain it partly to acknowledge the controversy which prompted our work. We also continue to use it to recognise one important aspect of this controversy which garnered public attention: the ways in which this material is co-produced through the web, digital platforms and their associated algorithms, bots, engagement metrics and use cultures.

The guide is freely available on the Public Data Lab’s website. It is released under a Creative Commons Attribution license to encourage readers to freely copy, translate, redistribute and reuse the book. A translation into Japanese is already underway. If you would like to translate the guide in other languages please get in touch with us. All the assets necessary to translate and publish the guide in other languages are available on the Public Data Lab’s GitHub page.

A number of universities and media organisations have been testing, using and exploring a first sample of the guide which was released in April last year. You can read more about this early release on the Nieman Lab or Columbia Journalism Review. BuzzFeed News also drew on several of the methods and datasets in the guide in order to investigate the advertising trackers used on “fake news” websites.

We hope the guide will be used to enrich public debate and catalyse collective inquiry around this evolving and contentious issue. This year, we will further develop this guide into a textbook to support teaching on journalism, new media and digital culture courses. If you would be interested in the textbook please sign up to be notified when it is released.

Download the English-language version of the guide at the Public Data Lab’s website.

Download the Japanese-language version of the guide.

Update (5/1/2018): A link to the now-completed Japanese-language version of the guide was added.