Pictures and video posted to social media have become crucial to how news organisations cover breaking news events, but the practice has emerged so quickly that ethical standards have been slow to catch up. How should journalists approach eyewitnesses on social media? What risks are they exposed to by providing their footage? And are news organisations using it responsibly?

A panel of experts at the recent International Journalism Festival in Perugia identified three key problems in how news organisations engage with eyewitnesses on social media and some potential solutions.

‘Harrassment’ of eyewitnesses during breaking news

At 07:59am on March 22, a bomb exploded metres from Belgian artist David Crunelle at Brussels Airport. Seconds later another bomb exploded. He staggered out of the terminal building, contacted family members and tweeted about the explosion. Within 20 minutes he started receiving phone calls from journalists, within an hour his phone was going crazy” and by 10am he had received “more than 10,000 notifications” on his phone.

2 explosions à bxl airport

— david crunelle (@davidcrunelle) March 22, 2016

Not all of these were from journalists, but many were. Seven hours later, his phone was still ringing.

It is now a common sight on social media to see journalists from around the world asking eyewitnesses at the scene of a news event for more information, for requests to use any images shared and to follow back or call the news desk.

But for an eyewitness this can be unmanageable, particularly in the wake of experiencing or seeing something horrific. Crunelle was complimentary about most of his interactions with the press, but there are many other cases and stories that differ.

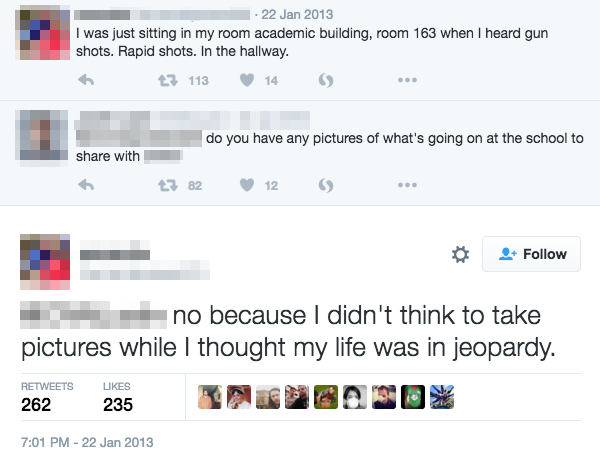

When Chris Harper-Mercer opened fire at Umpqua Community College in Oregon on October 1 2015, one student had a similar reaction to Crunelle. She sent two tweets and received hundreds of requests from journalists all asking the same thing.

She did not respond. Hundreds more Twitter users did, however, and their opinions were not positive.

The practice is widespread but is largely journalists doing their job under difficult circumstances in the only manner they know, said Fergus Bell, founder of Dig Deeper Media and co-lead on the Online News Association’s UGC Ethics Initiative. The cumulative effect reflects poorly on the industry, on news organisations and on individual journalists, however, and it is in everyone’s best interests to find a less damaging solution.

“We spend a lot of time and effort on engagement strategy” on social media, he said. “But there are tweets from reporters linked to your brand and they are out there for all to see. It’s undoing any work that you spend so much time and effort doing.”

And it can be particularly damaging when multiple reporters from the same organisation contact an eyewitness without communicating between each other, he said, as occurred during the campus shooting in Oregon.

“Individually they’re doing what journalists should do, but as an organisation – and this is going to be a problem in a large newsroom where there will be different programs, different teams and different shifts – you need to co-ordinate to reduce the risks to the individual and you need to co-ordinate to stop harrassing them.”

Possible solutions

Reportedly’s managing editor, Malachy Browne, raised the idea of a pooling system between news organisations for eyewitness media, yet fostering such co-operation across the industry would be very difficult, said Bell. It may be more possible among organisations which are part of a larger media group or company, however.

“There are a lot of groups of news organisations and papers out there,” he said. “Ultimately you want the papers and publications in your groups to do well. So it might make sense, instead of all of the organisations in that group reaching out, you can limit [the impact on eyewitnesses] by centralising [requests for contact].”

The Online News Association (ONA) recently published ethical guidelines for social newsgathering, but sometimes looking through an eyewitness’s posts and the responses can give a better idea about whether or how to contact them. But sometimes simply reading back through an eyewitnesses social history can help.

An eyewitness to the shooting on a beach in Tunisia in June 2015 gave a phone number and additional information about the scene in their comments, yet reporters continued to ask for contact details. During the Brussels attacks, an eyewitnesses who captured a video from inside the metro tunnels said reporters were free to use videos he had posted. Yet journalists continued to contact him.

The panel agreed that In the case of the UCC shooting, the eyewitness in question didn’t respond to any requests for contact, so adding to the litany of journalists in her mentions was unlikely to get the desired results, said Bell.

“Your editor might say you need to do this but it’s not going to work,” she said. “All you’re going to do is look bad and put someone at risk.”

Putting eyewitnesses in danger

“By communicating with people who are in a dangerous situation you are potentially putting them at risk” by revealing their location, said Bell.

Perpetrators of crimes are “increasingly” monitoring any response to their actions on social media, he said, and journalists need to be aware that sharing a picture or video in an active shooter situation may give away the location of an eyewitness, potentially making them a victim.

Even trying to contact an individual during an active shooter situation can put them in danger. They may have tweeted while hiding, or mistakenly thought they were safe, and the noise from a smartphone could alert the shooter to their position.

“It’s all very well to say they don’t have to check their phone until they are safe but the timing of such messages can be very important when you are protecting individuals,” said Bell.

Social media now allows reporters to “cross the police line” of a crime scene in a way never seen before, said Claire Wardle, co-founder of Eyewitness Media Hub and research director at the Tow Center for Digital Jornalism, and this can potentially put people at the scene in danger.

“When news organisations are saying ‘please go out… and send us your pics’, that is a form of commissioning,” she said. “None of these eyewitnesses have had hostile environment training, and there’s an issue here of understanding that they don’t understand the risks.”

Reportedly’s managing editor, Malachy Browne, argued that journalists need to think in more detail about information security when dealing with some eyewitnesses.

“The revelations of Edward Snowden showed us we must take much greater care in how we communicate with people in order to ensure their safety,” he said, “because we know that governments and other agencies are monitoring communications.”

The ability of journalists to amplify an eyewitness or source’s exposure to a bigger audience means they could potentially alert security services in a repressive regime, especially when contacting them on the open web.

Journalists have a responsibility to their online sources in the same way they do with offline sources, said Browne, and “understanding all of this as journalists affects how we approach sources and eyewitnesses on social” at Reportedly.

Possible solutions

For active shooter situations “there should be something in editorial guidelines that says nobody should contact an eyewitness until we know it’s over,” suggested Wardle. The proposal may be difficult to introduce but the alternative, at present, is to risk the lives of those still at the scene.

Browne advised journalists to get to grips with information security, like using encrypted messaging app Signal on an iPod touch for secure communication. The Electronic Frontier Foundation has a lot of information and guides, he said, which should be shared with sources who may be vulnerable.

Josh Stearns, founder of Verification Junkie and director of journalism and sustainability at the Geraldine R Dodge Foundation, advised journalists to review guides from Witness.org, particularly around the ethical use of video in human rights reporting.

Many newsrooms already have guidelines in place regarding source protection and anonymity, said Bell, so there should not be a need to start from scratch when looking at protecting eyewitnesses.

“It’s probably worth building on existing policies around anonymity,” he said. “Around sourcing, around communicating with sources and bringing in that technical element where we are now with social media.”

Crediting eyewitnesses appropriately

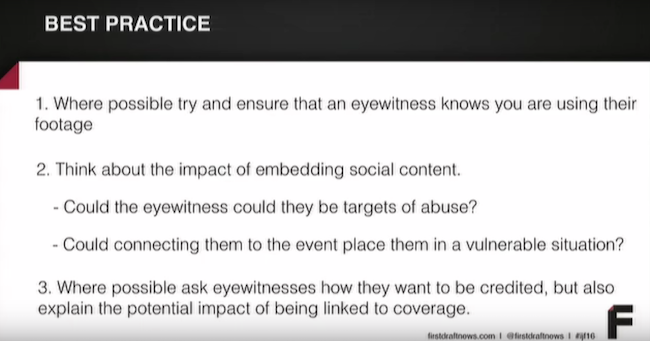

Sometimes an eyewitness will want to be credited, even paid, for providing footage from the scene of a breaking news event, but often they were just sharing something instinctively and don’t realise the repercussions of forever being associated with a story, said Wardle, “so the motivations of eyewitnesses are really important to consider”.

“Lots of people on Instagram have 50 followers and post pictures of cats for their family,” she said, “and have no idea journalists can do a location search and find their content. It’s never even considered that their material will be findable [by journalists].”

And once it is published, potentially to millions, it is very difficult to turn around and undo that exposure.

Research by Eyewitness Media Hub showed how the use of pictures or video from eyewitnesses without consulting them on crediting led to “racist trolls” contacting one individual. Another said they woke up to find their face and picture “all over the news”.

One eyewitness to the Charlie Hebdo shootings, who wished to remain anonymous, said: “What annoys me now is that if you do a search for me online there are as many references to AFP as there are articles [connected] to my actual work”.

“As journalists, we tend to focus on the breaking news event and forget that this stays,” said Wardle, “it stays on live blogs and therefore it stays in search and people’s names are connected to that.”

Many eyewitnesses are now becoming aware of the impact being associated with a news story through online crediting can have, but “there’s really no excuse for when eyewitnesses specifically ask for something… and it gets completely ignored,” said Wardle.

Possible solutions

Some ideas for best practice in using eyewitness media from Claire Wardle at #IJF16

The notion of “informed consent” is central to how Bell and his colleagues constructed the ONA Social Newsgathering Ethics Code. It also features in both the EMHub guiding principles on contacting eyewitnesses and AFP’s updated editorial standards and best practices.

“It’s our duty to talk about how their content will be used,” said Bell, “and how it will be up there forever, it will be searchable and are they happy to proceed.”

Watch the full talk at #IJF16 below