When news of the disappearance of Egypt Air flight 804 began circulating last week, many journalists went into “autopilot”. That was the assessment of James Warren, writing at the Poynter Institute

A series of recent reports highlights how this kind of speculation, passing on unverified information and sharing outright misinformation can erode trust between communities and newsrooms. Journalists who work on social media, cover breaking news or who are using eyewitness media, have to understand how trust is built and broken. A number of new studies highlight the unique contours of trust in online journalism and social media.

At a macro level, trust in media is already at dismally low levels. But recent research has begun to delve more deeply into those numbers to more fully understand how trust functions. Trust is the foundation on which journalism is built. There is no use in reporting if your journalism won’t be believed. But, in a new study released in April, the American Press Institute points out that there are financial implications for newsrooms as well.

“Americans who place the greatest emphasis on trust factors are most likely to pay, share or follow that source,” the authors write. “News organizations that earn trust have an advantage in earning money and growing their audience.”

Social media, trust and skepticism

The study, which was a partnership between the American Press Institute’s Media Insight Project and the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research, attempted to break trust down into “specific factors” that strengthen or erode trust and looked at new elements of trust that are unique to digital media. It included one section related to how people get news from social media and how trust is established and betrayed on those platforms.

They found that people who consume news on social platforms tend to approach that news with significant skepticism.

“Social media news consumers do not generally trust the news they see there,” write the authors. “Fewer than 1 in 4 of these social media news consumers, for instance, say they trust news and information from that source a great deal or a lot.”

People assess the validity of news on social media on a case-by-case basis, relying in large part on the original source of the news and the credibility of the person who shares it. As such, their decisions to trust any piece of news in the moment actually has roots in a longer relationship with the person or brand who shared and originated it.

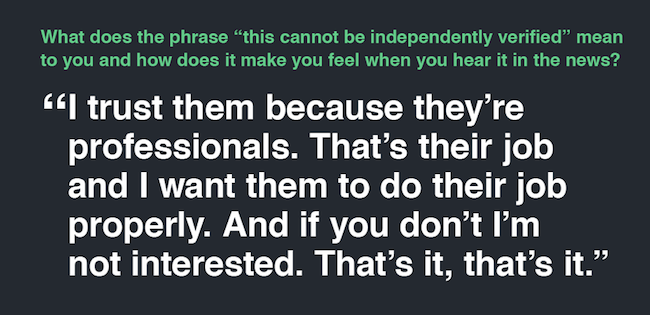

Last year, Eyewitness Media Hub (EMHub) conducted a series of interviews and focus groups with news audiences about their understanding of verification and eyewitness media. One of the key findings from the research was that audiences see verification as a core part of the reporting process and fundamental to the job of doing good journalism.

“There was a general sense that verification is an integral part of a journalist’s professional duty and that audiences place trust in them to perform this duty prior to publishing eyewitness media,” wrote the authors. “Failure to do so equated to a breach of trust and risked the integrity of the offending news outlet.”

In addition, the respondents in the EMHub study spoke about verification as “a key mechanism through which journalists add value to news outputs”. The publication of eyewitness media, without analysis or fact checking, was seen by many in EMHub’s focus groups as malpractice.

Trust takes a long time to build, but can be broken in an instant.

In a section specifically on why audiences lose trust in journalists and newsrooms the API researchers asked participants about specific instances where they felt their trust had been broken. While people struggled to come up with specific examples, the two most common categories were complaints over bias and inaccurate information. When newsrooms get the facts wrong, our communities take it personally.

Respondents in the focus groups “were able to articulate very emotional and visceral reactions to the situation,” wrote the authors. “Many focus group participants said they feel like they have been personally wronged, taken advantage of, or fooled when they have a bad experience with a news source.”

And mistakes, especially when handled poorly by the journalist or newsroom, undermine other reporting before and after the mistake.

If we get it wrong, make it right

Mistakes handled right and corrected quickly, however, can actually build trust. Indeed, Craig Silverman has argued that failing well may be the best way to build trust.

Having a clear corrections policy and providing the evidence to back up your reporting are two key factors identified by The Trust Project, an initiative at Santa Clara University’s Markkula Center for Applied Ethics with backing from Google and Craigslist founder and entrepreneur Craig Newmark. The project is developing indicators and has begun prototyping projects designed to “increase public confidence in news”.

Craig Newmark explains why he believes “a trustworthy press is the immune system of democracy”

Many of the indicators can inform how newsrooms operate during breaking news, employ eyewitness media and approach social newsgathering. Other recommendations from the indicators include providing deeper context, working with sources on-site, highlighting corrections and letting people follow to get story updates. Most importantly, throughout all of this, were recommendations to show the reporting and fact-checking process and allow people to interrogate it for themselves.

The issue of transparency came up in the EMHub research as well.

“Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the lack of information most news organisations divulge about this aspect of their workflow,” wrote the authors, “the people in our sample were largely oblivious to what the verification process entails or the extent to which skilled journalists are able to verify the finer details about a piece of eyewitness media.”

Indeed for some people in the study, while they deeply valued getting verified information, they equated the language of verification to jargon and said it felt like a gimmick.

For the last few months Joy Mayer, with the Reynolds Journalism Institute, has been studying how journalists can better build trust on social media. In a three part series she discusses a number of interviews and case studies from across journalism and other industries and argues that newsrooms need to tell their own story, engage authentically and deploy their “fans“.

Citing Kees Brants and his book “Rethinking Journalism: Trust and Participation in a Transformed News Landscape”, Mayer highlights that trust sometimes comes from feeling listened to and taken seriously. Brants lists reliability, credibility and responsiveness as defining characteristics of trustworthy journalism.

Those qualities were evident in the American Press Institute research as well. According to the study’s authors, several people said that “owning up to mistakes and drawing attention to errors or mistakes can show consumers that a source is accountable and dedicated to getting it right in the long term.” One focus group member, Kimberly, said “if they say ‘I messed up’ and take ownership, that makes me trust [them] more.”

And yet, as noted by Dan Gillmor in his book Mediactive, sometimes “transparency will lead your audience to trust you more, while they may believe you less”.

Perhaps that space between meaningful trust and healthy skepticism is exactly the balance we should seek.

2 thoughts on “How journalists build and break trust with their audience online”