This is the third in a series of new Essential Guides published by First Draft. Covering newsgathering, verification, responsible reporting, online safety, digital ads and more, each book is intended as a starting point for exploring the challenges of digital journalism in the modern age. They are also supporting materials for our new CrossCheck initiative, fostering collaboration between journalists around the world.

This extract is from First Draft’s ‘Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder’, by US director and co-founder Claire Wardle.

Download the full guide:

We live in an age of information disorder.

The promise of the digital age encouraged us to believe that only positive changes would come when we lived in hyper-connected communities able to access any information we needed with a click or a swipe. But this idealised vision has been swiftly replaced by a recognition that our information ecosystem is now dangerously polluted and is dividing rather than connecting us.

Imposter websites, designed to look like professional outlets, are pumping out misleading hyper-partisan content. Sock puppet accounts post outrage memes to Instagram and click farms manipulate the trending sections of social media platforms and their recommendation systems.

Elsewhere, foreign agents pose as Americans to coordinate real-life protests between different communities while the mass collection of personal data is used to micro-target voters with bespoke messages and advertisements. Over and above this, conspiracy communities on 4chan and Reddit are busy trying to fool reporters into covering rumours or hoaxes.

Words matter and for that reason, when journalists use ‘fake news’ in their reporting, they are giving legitimacy to an unhelpful and increasingly dangerous phrase.

The term ‘fake news’ doesn’t begin to cover all of this. Most of this content isn’t even fake; it’s often genuine, used out of context and weaponised by people who know that falsehoods based on a kernel of truth are more likely to be believed and shared. And most of this can’t be described as ‘news’. It’s good old-fashioned rumours, it’s memes, it’s manipulated videos and hyper-targeted ‘dark ads’ and old photos re-shared as new.

The failure of the term to capture our new reality is one reason not to say ‘fake news’. The other, more powerful reason, is because of the way it has been used by politicians around the world to discredit and attack professional journalism. The term is now almost meaningless with audiences increasingly connecting it with established news outlets such as CNN and the BBC. Words matter and for that reason, when journalists use ‘fake news’ in their reporting, they are giving legitimacy to an unhelpful and increasingly dangerous phrase.

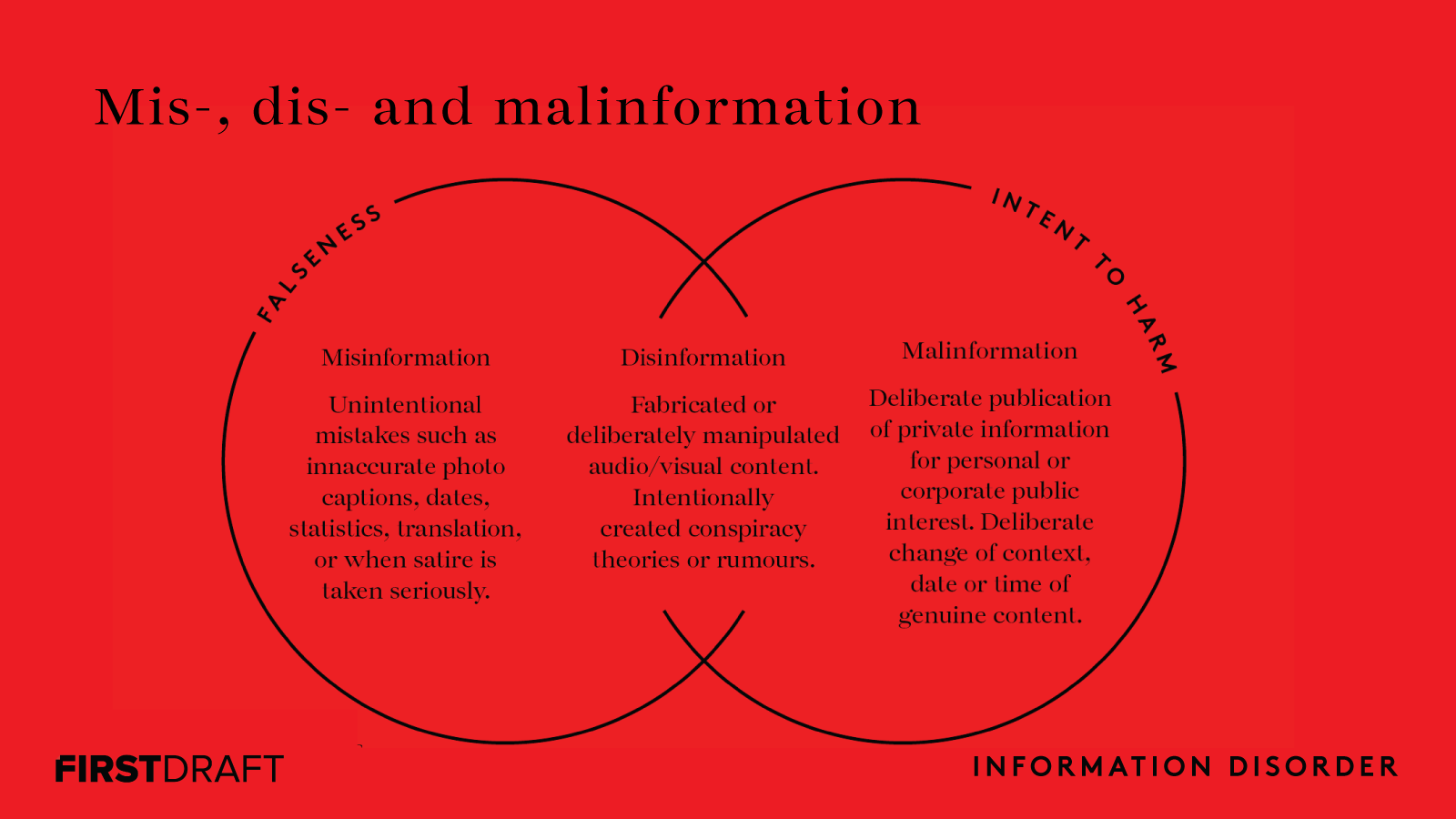

At First Draft, we advocate using the terms that are most appropriate for the type of content; whether that’s propaganda, lies, conspiracies, rumours, hoaxes, hyperpartisan content, falsehoods or manipulated media. We also prefer to use the terms disinformation, misinformation or malinformation. Collectively, we call it information disorder.

Disinformation, misinformation and malinformation

Disinformation is content that is intentionally false and designed to cause harm. It is motivated by three distinct factors: to make money; to have political influence, either foreign or domestic; or to cause trouble for the sake of it.

When disinformation is shared it often turns into misinformation. Misinformation also describes false content but the person sharing doesn’t realise that it is false or misleading. Often a piece of disinformation is picked up by someone who doesn’t realise it’s false, and shares it with their networks, believing that they are helping.

The sharing of misinformation is driven by socio-psychological factors. Online, people perform their identities. They want to feel connected to their “tribe”, whether that means members of the same political party, parents that don’t vaccinate their children, activists who are concerned about climate change, or those who belong to a certain religion, race or ethnic group.

Agents of disinformation have learned that using genuine content — reframed in new and misleading ways — is less likely to get picked up by AI systems.

The third category we use is malinformation. The term describes genuine information that is shared with an intent to cause harm. An example of this is when Russian agents hacked into emails from the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign and leaked certain details to the public to damage reputations.

We need to recognise that the techniques we saw in 2016 have evolved. We are increasingly seeing the weaponisation of context, the use of genuine content, but content that is warped and reframed. As mentioned, anything with a kernel of truth is far more successful in terms of persuading and engaging people.

This evolution is also partly a response to the search and social companies becoming far tougher on attempts to manipulate their mass audiences.

As they have tightened up their ability to shut down fake accounts and changed their policies to be far more aggressive against fake content (for example Facebook via its Third Party Fact-Checking Project), agents of disinformation have learned that using genuine content — reframed in new and misleading ways — is less likely to get picked up by AI systems. In some cases such material is deemed ineligible for fact-checking.

Therefore, much of the content we’re now seeing would fall into this malinformation category — genuine information used to cause harm.

Seven types of mis- and disinformation

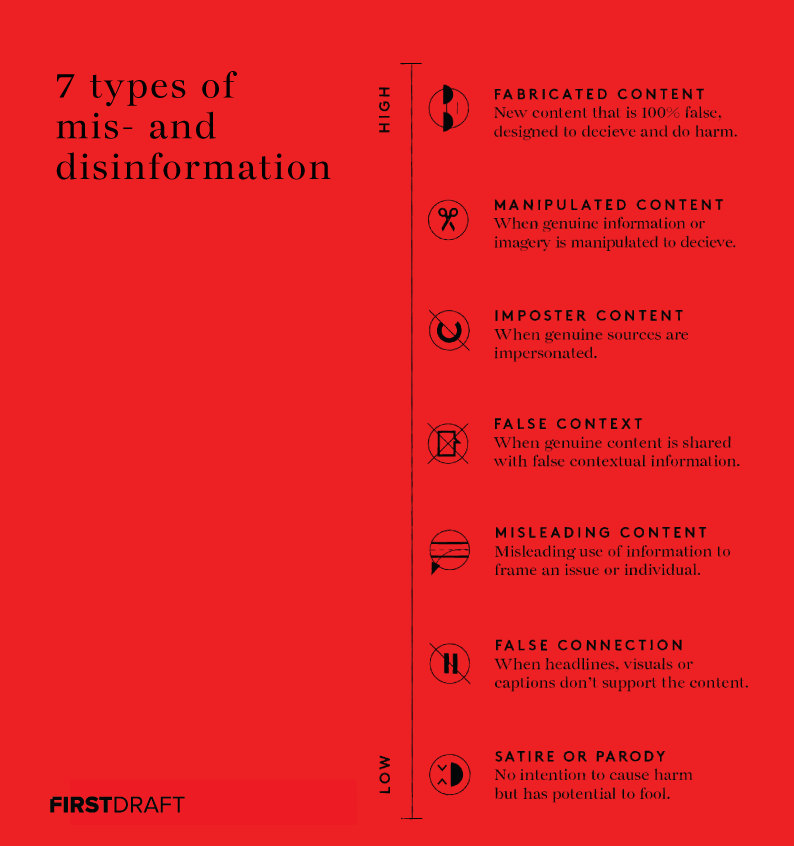

Within these three overarching types of information disorder, we also refer frequently to seven categories, as we find that it helps people to understand the complexity of this ecosystem.

They were first published by First Draft in February 2017 as a way of moving the conversation away from a reliance on the term ‘fake news’. It still acts as a useful way of thinking about different examples.

As the previous diagram shows, we consider this to be a spectrum, with satire at one end. This is a potentially controversial position and one of many issues we discuss over the course of this book, through clickbait content, misleading content, genuine content reframed with a false context, imposter content when an organisation’s logo or influential name is linked to false information, to manipulated and finally fabricated content.

Information disorder is complex. Some of it could be described as low-level information pollution — clickbait headlines, sloppy captions or satire that fools — but some of it is sophisticated and deeply deceptive.

In order to understand, explain and tackle these challenges the language we use matters. Terminology and definitions matter.

There are so many examples of the different ways content can be used to frame, hoax and manipulate. Rather than seeing it all as one, breaking these techniques down can help your newsroom and give your audience a better understanding of the challenges we now face.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.