Mis- and disinformation moved up the news agenda over the last 12 months as researchers, journalists and the public faced unprecedented problems navigating the online news ecosystem. Information Disorder: Year in Review hears from experts around the world on what to expect and how to be more resilient in 2020.

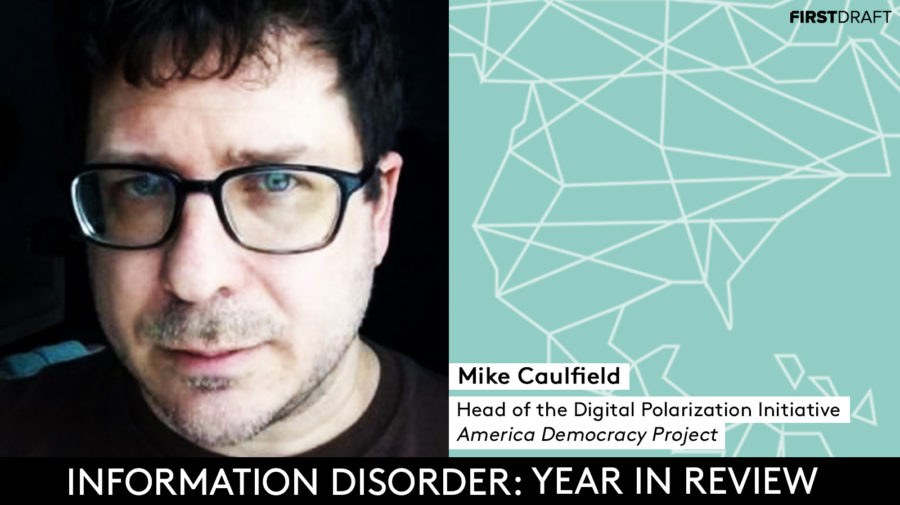

Mike Caulfield is the head of the Digital Polarization Initiative of the American Democracy Project, a national project to build web literacy among the American public. He works at Washington State University, and lives near Portland, Oregon.

First Draft: What was the biggest development for you in terms of disinformation and media manipulation this year?

Mike Caulfield: This is a very US-centric perspective, but the institutionalisation of it. That’s in a number of ways, but most notably we’re sitting through an impeachment process right now that is based on an improper request for a server that exists only in conspiracy mythology.

In my more limited area of online information literacy, I’m biased, but I think the $50 million Knight Foundation move to create a network of professional disciplines around misinformation may turn out to have beneficial effects many years from now. We are starting to finally see the cross-disciplinary collaborations we need to move forward in this field.

“It’s easy enough for disinformation agents and motivated spinners to attack normalcy while leaving the facts in place” – Mike Caulfield

What is the biggest threat journalists in your part of the world are facing in 2020 in terms of information disorder?

Facts are nice, but people use a few simple heuristics when it comes to opinion formation. One of the big ones is just “Is this normal?” And disinformation targets this, making normal things seem suspicious and dramatically abnormal things seem business as usual.

You see this with the death of [Jeffrey] Epstein. People act like the facts of faked logs or fractured vertebrae tell people something but they are meaningless without guidance on whether they are normal or not. It’s the guidance that’s the main thing.

Likewise, there will be voting irregularities in the US in 2020. There will be an impeachment. There will be climate events.

And the questions people will be asking when deciding whether to devote their scarce attention to an issue will be: “Is this something that happens randomly to everyone, or is it targeted? Is this something historically unique, or the same-old/same-old?”

It’s a good part of the reason we’re headed to the untold misery of the climate crisis. It’s why 2016 happened as it did. It’s a big part of why people are ho-hum about our current crisis of democracy.

— Mike Caulfield (@holden) 22 December 2019

It’s easy enough for disinformation agents and motivated spinners to attack normalcy while leaving the facts in place, you just flood people with additional facts. Here’s an instance of a hotter day from 1973, global heating is fiction. Or here is an expert saying that the Epstein logs are very unusual and unlikely to happen without a broad conspiracy. Here’s someone saying that Jimmy Carter actually did something very like the Ukraine call. Here’s someone saying that they’ve never heard of voting machines malfunctioning in this way. Or here’s someone saying voting machines malfunction like this all the time.

Digitally-distributed social media excels at separating facts from context. Facts become atomised and disaggregated, consumed as headlines or recombined into new, ill-fitting narratives. Both-sides journalism creates a world where every event is both the most dire threat to the republic since its founding and also just business as usual.

In a world of infinite data points, the usual can be made deeply suspicious, and the earth-shattering can be made to seem ho-hum. Put these things together and the future looks very bleak.

What tools, websites or platforms must journalists know about going into 2020?

There are lots of new and cool tools but I would say the biggest gaps I see are in the lack of habitual use of basic tools. You should be right-click searching names, URLs, images and the like almost as much as you click links.

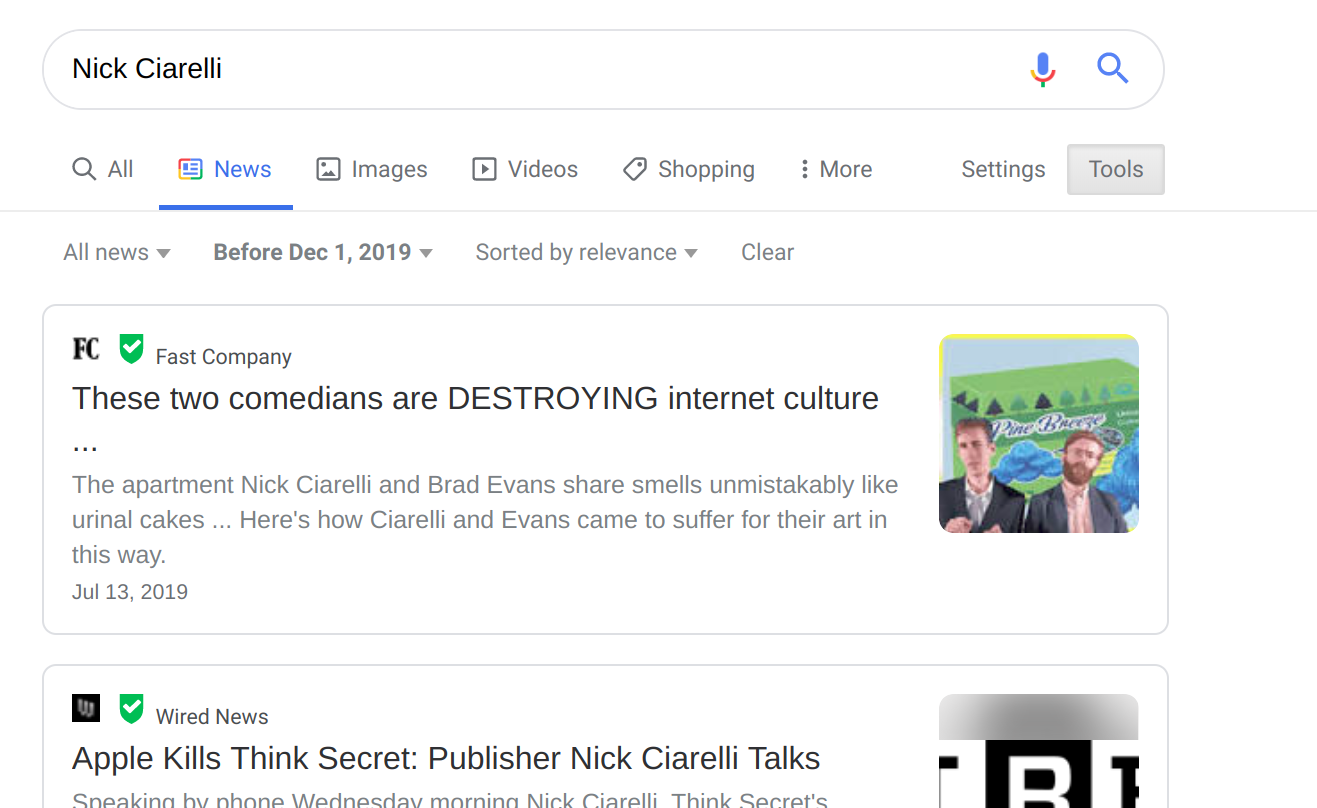

For example, here’s what a right-click news search of “Bloomberg intern” Nick Ciarelli [a comedian behind a recent viral video poking fun at 2020 election wannabe Mike Bloomberg] would have shown people in less than 10 seconds:

Screenshot: Mike Caulfield

The MovesLikeBloomberg thing was harmless of course, and got comparatively little lift next to other trends. But it serves as a reminder that the most destructive errors of the coming year won’t be because someone didn’t know the correct tools to check the sun’s azimuth for a video location-check. They’ll be because someone didn’t take ten seconds to see a quote in context, do a news check on a name, or trace a video to its source.

What was the biggest story of the year when it comes to these issues of technology and society?

Honestly, in the US it was the pursuit of the Crowdstrike server in the Ukraine call. This is an example of a disinformation campaign so successful that it is guiding the actions of a sitting president. The implications of that are staggering.

When it comes to disinformation in your country, what do you wish more people knew?

In the US, many want to see disinformation as a battle of numbers, a ‘direct effect’ model of democratic influence that no one has taken seriously since the mid-20th century.

In fact, disinformation is highly mediated and targets points of influence and power. The main impacts of disinformation are felt indirectly, amplified and disseminated by opinion leaders, mid-level elites, activists.

Sometimes disinformation skips the broader public altogether, choosing to directly target lawmakers or law enforcement. The crisis in America is not in the broad belief of individuals in crazy theories but in the growing influence of these campaigns on those with their hands on the levers of power and influence.

A Check, Please! style walkthrough on the Manuilsky Hoax, a Cold War example of quote fabrication https://t.co/KRvebvV6ra

— Mike Caulfield (@holden) November 24, 2019

If you had access to any form of platform data, what would you want to know?

Real-time dashboards that help identify developing stories, themes and claims and show some basic parameters about whether the story is about to break out into public view, eg what’s the current level of checkmark engagement. Paid versions of these exist, but if platforms like Twitter and YouTube would put out better and more integrated versions then journalists, researchers, and information activists could work together to better monitor emerging issues. And media literacy folks like me could spend less time looking for class examples.

This interview was lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.