As details about the men accused of carrying out the deadly attacks across Paris began to surface, unveiled by French police and prosecutors, the world’s media turned to social to find out more about the suspects.

But by that time, many of their accounts had already been removed.

Tracking extremists on social media presents a multitude of challenges, one being the rapid rate at which their profiles are being purged. Facebook and Twitter are working aggressively to shutter accounts linked to the Islamic State (IS) and ban the dissemination of its propaganda, aimed at luring recruits.

As attacks broke out in Paris on November 13, social networks rushed to remove pro-Islamic State accounts praising the attacks with the hashtag باريس_تشتعل# (“Paris on fire”). With social networks cracking down on posts like these, thousands of Islamic State supporters migrated to Telegram, an encrypted messaging application that allows users to send content via “channels” to an unlimited number of recipients.

In light of the Paris attacks, Telegram began shutting down Islamic State channels, announcing in a tweet on November 18 that it had blocked 78 IS-related channels across 12 languages.

This week we blocked 78 ISIS-related channels across 12 languages. More info on our official channel: https://t.co/69Yhn2MCrK

— Telegram Messenger (@telegram) November 18, 2015

It seems that as quickly as pro-IS accounts surface on social, they are often as swiftly deleted. Yet some still slip through the cracks. One of those was “Billy Du Hood,” an account belonging to the suicide bomber Bilal Hadfi. A source close to the investigation identified Hadfi on November 16 as one of seven assailants who died during the attacks in Paris, which left at least 130 people dead.

Hadfi detonated his suicide vest outside a McDonald’s restaurant just meters from the Stade de France, where soccer fans had gathered to watch the France vs Germany match. No one else was killed in the blast.

Hadfi, a 20-year-old French national, was known to have returned to Belgium from the Middle East before disappearing from the radar of security forces, The Washington Post reported. According to the Belgian newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws, Hadfi was connected with an Islamic State sleeper cell based in the Molenbeek district of Brussels, where the Paris attacks were conceived. Hadfi, from the nearby Brussels neighborhood of Neder-over-Heembeek, was reportedly an avid soccer fan until the spring of 2014, when he quickly became radicalized by a Belgian imam, later moving to Syria in early 2015.

According to the same report, Hadfi became Facebook friends with a number of hardline extremists, including Abu Isleym, a Syrian extremist who has been pictured with a beheaded victim of IS. A search for Bilal Hadfi returned a few results on Facebook, among these was the page of a “Billy Du Hood” (username, “berkanoh.versailles”).

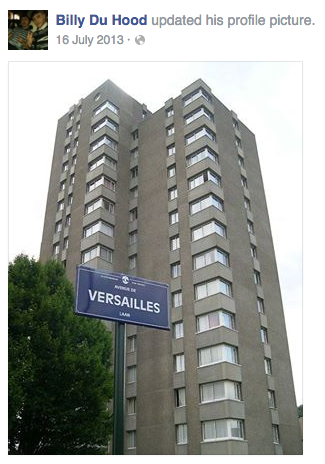

Versailles, a housing estate in Neder-over-Heembeek, features in a number of images on the same profile. It is also the name of a violent street gang with which Hadfi was reportedly linked. The image below shows a group of young men posing at the street sign for 144–146 Avenue de Versailles in Brussels, which tallies exactly with this street view of the same location on Google Maps.

Images of the Versailles housing estate in Neder-over-Heembeek shared publicly on the Facebook account for Billy Du Hood in July 2013 and November 2014, respectively

The Billy Du Hood account was taken down on November 16 as Storyful was working to verify it. The pages and images were archived by Bellingcat, whose investigative unit discovered the profile on the same date. The photos on the Facebook page tally with the image of Hadfi shared by Het Laatste Nieuws (below).

Belg Bilal Hadfi blies zichzelf op aan Stade de France https://t.co/u1g6jAbKVO #hln pic.twitter.com/QFH3PDBFEN — HLN.BE (@HLN_BE) November 16, 2015

One of the first images of Hadfi shared in reports naming him as one of the Paris attackers. The photo, which appeared in Het Laatste Nieuws, was sourced by Guy Van Vlierden from one of Hadfi’s alternate Facebook accounts

Guy Van Vlierden, a journalist for Het Laatste Nieuws who specializes in issues related to terrorism, told Storyful that he had tracked several other accounts linked to Hadfi, but that those with the clearest extremist content had all disappeared. The image of Hadfi holding up a finger (above) was obtained by Van Vlierden from one of those Facebook accounts.

Hadfi, writing on Facebook under the pseudonym Bilal Al Mouhajir, put out a call to arms in a post in July. Van Vlierden reported on the post, and shared a screengrab of it on Twitter.

The message refers to westerners as “those dogs who attack our civilians” in various Middle Eastern cities, and appeals to “brothers working in the land of nonbelievers” to “work within their community of pigs so they can’t feel safe again, even in their own dreams”. (This is a translation of “travaillez au sein de,” which is misspelled in the message as “travaillez aux sain de.”)

This is what #ParisAttacks suicide bomber #BilalHadfi wrote in July – supposedly from Syria. pic.twitter.com/Ki7JrER9CV

— Guy Van Vlierden (@GuyVanVlierden) November 18, 2015

But what appears to have been Hadfi’s personal account, Billy Du Hood, also left evidence of extremist ties.

One of Billy Du Hood’s Facebook friends, Naail*, commented on a few of his photos with the word “DAIICH”, an alternative spelling of Daesh, an acronym for the Islamic State’s full Arabic name that is seen as an insult by the group. According to the Boston Globe’s Zeba Khan, Daesh can mean both “to trample down and crush” or “a bigot who imposes his view on others,” depending on how it is conjugated in Arabic.

Naail commented “oui DAIICH” on this group photo, which was shared by the Billy Du Hood Facebook account in June 2014. The third comment on the photo also lists Bilal Hadfi’s full name

Naail confirmed to Storyful that the Facebook account Billy Du Hood belonged to Bilal Hadfi — his cousin. Naail, who lives in Morocco, said when he was contacted by Storyful that he did not know Hadfi was linked to the attacks.

In a series of messages on Facebook, Naail told Storyful that he had not spoken with Hadfi in two years “because he is in DAAICH”. He said the last time he saw Hadfi was in Saidia, a beach in Berkane, Morocco, in August 2014. According to Naail, the photograph below of Hadfi wearing a swimsuit and holding a cocktail, which was posted on August 2, 2014, was taken in Turkey. He said that Hadfi had traveled to Turkey before meeting him in Saidia.

A photo of Hadfi shared on the Billy Du Hood Facebook account on August 2, 2014. According to Naail, this image of Hadfi was taken in Turkey. Storyful could not independently confirm the location

Abdel*, one of Hadfi’s former high school classmates at the Sint-Pieterscollege Jette in Brussels, whose name has been changed here to protect his identity, shared an article about Hadfi’s involvement in the attacks on Facebook, writing, “One of the terrorists that blew himself [sic] at the French stadium used to do taekwondo with us and was at my school, I feel disgusted and shocked at the same time.” A number of people responded in comments to the post, many of whom said they recognized Hadfi and were stunned by his involvement in the attacks.

A screenshot of Abdel’s Facebook post, voicing his shock over Hadfi’s involvement

In a conversation with Storyful on Twitter, Abdel described Hadfi as a soft-spoken teenager, who liked taekwondo and video games.

“When he was at Sint-Pieters he used to hang with us,” Abdel said. “He was shy but kind. He was just a normal kid, like all of us.”

A class photo, shared by Abdel with Storyful, is described as showing Hadfi in his second year of high school at Sint-Pieterscollege. The buildings pictured in the background tally with photos of the school on its website

Hadfi, then a baby-faced teen, changed drastically after Abdel lost touch with him, shortly after this photograph was taken.

His new interests and extremist views were implicit in the public posts on his Facebook page. His more recent posts ranged from comments of “nique la police” (“fuck the police”), to an illustration of a man smoking marijuana, photos showing stacks of money, and images of Kalashnikovs, the same weapons as used in the Paris attacks.

A series of posts shared on the Billy Du Hood Facebook account from 2013 to 2015, which disappeared when the page was removed

Hadfi’s last public post, shared on August 18, 2015, shows him giving the middle finger.

The most recent photo posted publicly to the Billy Du Hood Facebook account was shared on August 18. It appears to show Hadfi with a friend, giving the middle finger

Of course, similar material to all this is shared on tens of thousands of Facebook pages daily, thus pointing to the difficulty in monitoring this kind of online activity. In retrospect, it can help fill in the gaps for investigators and journalists to chart a person’s progression along a path to extremism and violence. But as a predictor of such behavior, such material alone is not enough.

Nevertheless, despite the repeated flagging and removal of terror-related content, the multiplicity of Hadfi’s accounts alone shows that, while one pro-IS profile or account might be successfully removed, several more will spring up, Hydra-like, in its place.

*This name has been changed to protect the source’s identity.

Parts of this report were originally published on Storyful’s Newswire on November 16.