Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey declared on Wednesday that his company will “stop all political advertising on Twitter globally“, a shrewdly-timed move which will turn up the heat on Mark Zuckerberg’s decision to not only allow political ads on Facebook, but exempt political advertising from fact checks altogether.

Published within 48 hours of the UK Parliament’s decision to hold a general election, Dorsey’s Twitter thread offered a few hundred words of platitudes on the world platforms like his have helped create, but very little detail on what to do next. It may have been intended as an antidote to misinformation and multiplicity but Twitter’s existing efforts show it has a long way to go to solve the problem.

We’ve made the decision to stop all political advertising on Twitter globally. We believe political message reach should be earned, not bought. Why? A few reasons…?

— jack ??? (@jack) October 30, 2019

If Dorsey’s announcement was big-picture posturing then Vijaya Gadde, who lists her role as “legal, policy and trust & safety lead” for Twitter in her verified account bio, shed a little more light on how decisions might be made.

Responding to one journalist’s question about “what constitutes an issue ad”, she explained the company’s working definition as: “1/ Ads that refer to an election or a candidate, or 2/ Ads that advocate for or against legislative issues of national importance (such as: climate change, healthcare, immigration, national security, taxes)”.

hi – here’s our current definition:

1/ Ads that refer to an election or a candidate, or

2/ Ads that advocate for or against legislative issues of national importance (such as: climate change, healthcare, immigration, national security, taxes)— Vijaya Gadde (@vijaya) October 30, 2019

Even a cursory thought experiment on how these definitions might be policed and enforced raises difficult questions which Twitter is yet to show it is able to answer.

If the company uses computer power to detect political advertising “globally”, it will need to build and maintain a database of all political parties, candidates, issues and keywords in every country and language, forevermore. That is certainly not impossible, but goes above and beyond what Twitter has so far committed to the issue of political advertising on its platform.

In May 2018, just in time for the US midterms, Twitter announced its Ads Transparency Center. The company billed it as a service which “allows anyone across the globe to view ads that have been served on Twitter”.

The devil, as is often the case, was in the details. While anyone might be able to access the library, the amount of information available is slim. Users can search for any account and the library will show whether it has promoted any ads in the last seven days. It is only accounts which have “self-identified” as political campaigners, however, which show anything approaching transparency.

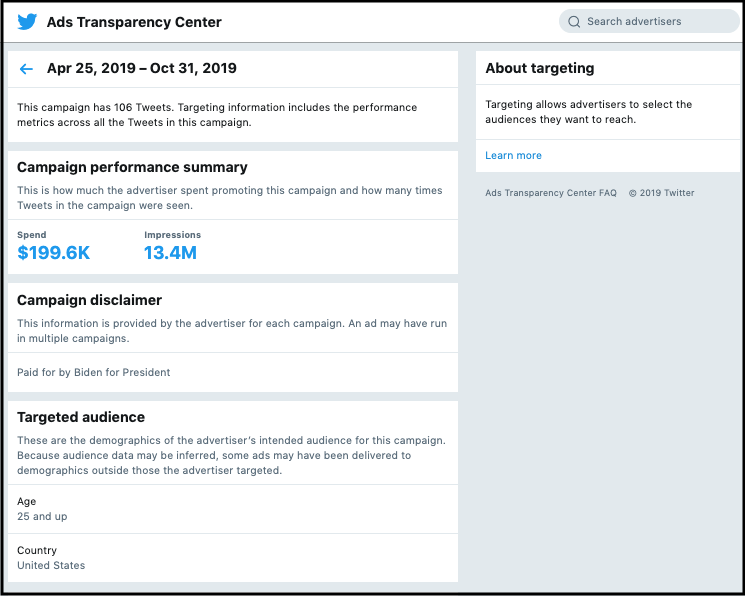

The official account for former vice-president Joe Biden is one of those “certified” for political campaigning. Visitors to his page in the Ads Transparency Center can view dozens of promoted tweets going back months, with information about who paid the bill and how much has been spent.

Visitors can click a link on each advert marked “ad details” and see precisely how much Biden’s campaign has pumped into each advert, which demographics they targeted and how many impressions it received. The library even breaks down the demographics of the audience Biden managed to reach, including age brackets, gender, language, region and city.

Information from Twitter’s Ads Transparency Center on one of Joe Biden’s recent promoted tweets. Screenshot by author.

Donald Trump, however, has not registered as an advertiser so there is no information on whether his account ran ads in the last seven days or, in fact, at any time in the past at all. The same goes for the Republican National Committee. It can be easily argued that Trump doesn’t need to pay to reach people on Twitter given how almost every tweet is reported as breaking news. But the fact that no one can see if he has or not is an affront to the transparency Twitter claims to promote.

In the UK, neither the Conservatives or the Labour Party or either of their leaders have “self-identified” as advertisers, so there is no information available on whether they have ever run ads on the platform. The same goes for Brexit campaign groups like Leave EU, People’s Vote or minor parties like the resurgent Liberal Democrats or Greens.

The Brexit Party and pro-EU group Best for Britain have both paid for ads in the last seven days but, because they have not “self-identified”, users can’t see any background information about how much was spent and how they were promoted. Viewed through Twitter’s Ad Transparency Center, the state of political advertising in the UK could not be more opaque if it tried.

All this does not begin to address the fact that Dorsey has promised to ban *all* political ads, not just those from candidates or parties. A case in point in how difficult this may be came in early October, when a Twitter advert shown to UK users promoted a World War 3 strategy game which used the slogan from this year’s Conservative Party conference.

Featuring a video of cartoon gunships surrounding the British Isles and mushroom clouds over Munich, the tweet reads: “Will you work together with the EU? Or will you get Brexit done?”

A tweet for a video game promoted to UK Twitter users. Screenshot by author.

Observers could debate whether this constitutes political advertising or not, but the fact of the matter is it uses a political slogan and political subject matter. It could arguably inflame political sensitivities dependent on which side of the Brexit debate a viewer might fall. And it may not be pushing a legislative agenda but it would almost certainly be caught by any language-processing software employed to look for Brexit-related material.

But is it political advertising? If Twitter’s current policy on the matter is anything to go by, the question is almost moot because the advertiser hasn’t self-identified. There is no information about how much was spent on the campaign or who it targeted.

In wrapping up his thread on the subject, Dorsey said his company would share the final policy on November 15, with a view to start enforcing it a week later. He said nothing to address the perennial issues of abuse directed at public figures, especially women, or inauthentic and automated information campaigns which boost political messages without the need for advertising, two issues which the platform has yet to solve.

Whether this plan has been formed as a way to upstage Facebook on an issue it is struggling to address or a concerted effort to clean up the platform will very much depend on whether he has found answers to these questions, and more.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of First Draft.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.

Correction: This article has been corrected to state that Jack Dorsey announced the policy to ban political advertisements on Wednesday. A previous version said that he announced the decision on Thursday.