On the morning of August 21st 2013, reports began to appear online from opposition groups in Damascus, claiming chemical attacks had occurred in different areas of the city.

While reports of alleged chemical attacks were not unusual at the time, the initial stories coming from Damascus on August 21st were unusual for the size of the attack that was being reported, and the amount of supporting content being posted online.

Earlier alleged chemical attacks would generally produce a handful of videos and photographs, as well as a few posts by local groups on sites such as Twitter and Facebook, but on August 21st dozens of images were being shared online by multiple groups across Damascus.

Identifying the munitions

Despite the many videos of victims being treated in hospitals and clinics coming from opposition groups, there was still the question of whether or not this was a chemical attack.

It was impossible to establish the specific type of chemical agent used from the video footage of victims alone, and potentially it could have been a conventional attack that hit chemical storage facilities that may have been located in the target areas. Therefore, establishing the type of munitions used was a top priority.

Videos and photographs posted from one of the areas effected, Eastern Ghouta, gave the first clues to the type of munition used.

The images from Eastern Ghouta showed the same type of munition in several locations, and each example appeared to be mostly intact, apart from damage to the front of the munition. These were virtually unknown, even to arms experts and those following the conflict in Syria closely.

However, during my own research into the conflict in Syria I had encountered the same type of munition on multiple occasions, and that provided key clues to the nature of the munition, and who would have deployed it.

The following video shows the remains of munitions from another alleged chemical attack in Adra, Damascus, on August 5th 2013.

Syrian opposition groups in the area alleged that this was an attack by the Syrian military on their positions, and it’s clear the munition used is the same type used on August 21st 2013.

The remains of the same type of rocket had also been filmed in Adra in June 2013, Daraya, Damascus at the start of the 2013, and again in Daraya in December 2012. Unlike the August 21st attacks in Damascus these earlier attacks had far lower numbers of casualties, and went virtually unnoticed by the world’s media.

While it was possible to show the munition had been used in past alleged chemical attacks thanks to images shared on social media, there was still more to learn.

There was much discussion online about how the munition actually functioned, and I participated in a discussion with military experts in a private forum where we could openly discuss and test various theories. A breakthrough moment came when local activists shared dozens of images of the remains of one of the munitions, including measurements and close up images of key parts.

From this it was possible to establish some essential information about the munition. For example, we identified that the front of the munition was the remains of the warhead, and a small explosive charge was used to break open the casing that had been present before the munition detonated.

This showed the munition was designed to distribute a payload, rather than cause explosive damage. The base of the warhead had two ports, one of which was a screwcap, which showed that it couldn’t have been filled with a gas and using a small port to fill it with a solid would have been very difficult, so the likely fill would have been a liquid. In the context of a chemical attack this reduced the number of potential chemical agents that could have been used.

Later investigation would establish that these rockets were known as “Volcanoes”, but they were not the only rocket used on August 21st. While the Volcano rockets had landed in the east of Damascus, the attacks in the west of Damascus had used a different type. These rockets were examined by UN/OPCW inspectors on August 27th.

We established the type of artillery rocket using the inspectors own measuring tape to measure the width of the munition. By cutting and pasting the measuring tape filmed in the video it was possible to establish that the munition was 140mm wide.

This immediately reduced the number of artillery rockets it was likely to be, and reference material on artillery rockets show that it matched a M14 140mm artillery rocket.

As with the Volcano rockets in East Damascus, only the warhead was damaged, suggesting a low explosive warhead. In fact, reference material on the M14 140mm rocket showed one potential warhead was a Sarin filled warhead.

Despite frequent references to “Sarin gas” in the media, Sarin is in fact a liquid, and would also be a possible fill for the Volcano rockets seen in East Damascus. Records discovered by Human Rights Watch would also show that the same type of rocket was sold to the Syrian government and no evidence has ever been produced showing Syrian opposition groups using either the M14 rocket or the Volcano rocket.

The launchers and Volcano variants

A week after the chemical attacks in Damascus, a video was posted online showing what appeared to be a Volcano rocket being fired by what was claimed to be Syrian government forces.

This video actually presented a new twist to the tale of the Volcano rocket. In videos of the Volcano rockets from August 21st, the length of the rocket motor (below the warhead) was about shoulder height to the men who were displaying the remains.

In this video the rocket motor appeared to be much longer, and this established there were in fact two different sizes of the munition. Shortly afterwards new videos appeared showing another variation of the Volcano rocket.

This video showed the remains of a Volcano rocket being dissembled by a Syrian opposition group, with the warhead packed with explosives. Had this warhead detonated it would have destroyed the entire rocket, which seemed to indicate there was both a chemical version of the rocket and an explosive version.

Other interesting details were noticeable in the videos of Volcano rockets. For example, Volcano rockets linked to chemical attacks only ever had red numbering on them, while explosive examples had black numbering.

Also notable on the explosive Volcano rocket was the absence of the fill port identified on the chemical variant, further confirming there was a chemical and explosive version of the Volcano rocket.

Launchers for the smaller type of Volcano rockets began to appear online, confirming that in addition to there being two types of payload, there were also two different sizes of rockets.

The following videos filmed by local opposition groups show launches of explosive Volcano rockets from Mezzeh airbase in Damascus in late 2012, with a clear view of the twin barrel launcher used for smaller Volcano rockets at the end of the video.

A couple of months after August 21st, after the threat of US airstrikes had subsided, videos began to appear on pro-Syrian government channels showing both the larger single barrel launchers and twin barrel launchers being used by the Syrian military, further confirming the use of Volcano rockets by government forces.

In the two years since the August 21st attacks, no evidence has appeared showing that Syrian opposition groups have had access to Volcano rockets or their launchers, and the Syrian government itself confirmed with the OPCW that none of its chemical weapons had been captured by the Syrian opposition.

This information alone would present a compelling case, but it was possible to extract much more information about the attacks from open sources.

The launch site

The UN/OPCW report published on the August 21st attacks confirmed that Sarin had been used, and that M14 140mm artillery rockets and Volcano rockets were found at the impact sites, matching the information discovered through open source investigation. Because the UN/OPCW was not mandated to name the perpetrators of the attack the question of who was responsible was still being debated. While it could clearly be demonstrated that the Volcano rockets and M14 140mm artillery rockets were in the Syrian governments arsenal there were still attempts to blame the opposition.

One focus was the range of the Volcano rockets, and the likely launch site, with one video in particular giving the first clue.

This video, showing a pro-government group launching the explosive type of Volcano rocket, was unusual as it showed the launch and impact in one shot. By timing the difference between the flash of the impact and the sound of the explosion it was possible to use the speed of sound to calculate the approximate range, around 2km.

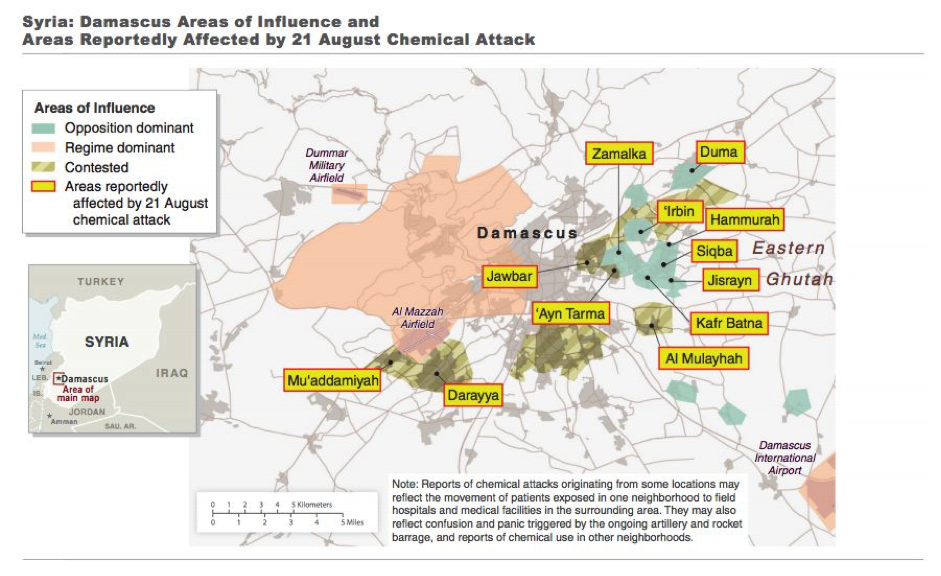

This sparked a new debate on who was responsible for the attack as the US government had produced the following map in the wake of the August 21st attacks, claiming they knew where the rockets had been fired from.

The areas marked ‘regime dominant’ were more than 2km away from the ‘contested’ and ‘opposition dominant’ areas, so according to this map it would have been impossible for the Volcano rockets to have been launched by government forces. However, this map is deeply flawed. Large areas are unmarked, the definition of “dominant” is unclear, and open source investigation would show key information was missing from the map.

(The range of the M14 140mm artillery rockets were well within range of government bases, and their use was broadly ignored by those attempting to show the Syrian opposition were responsible for the attacks.)

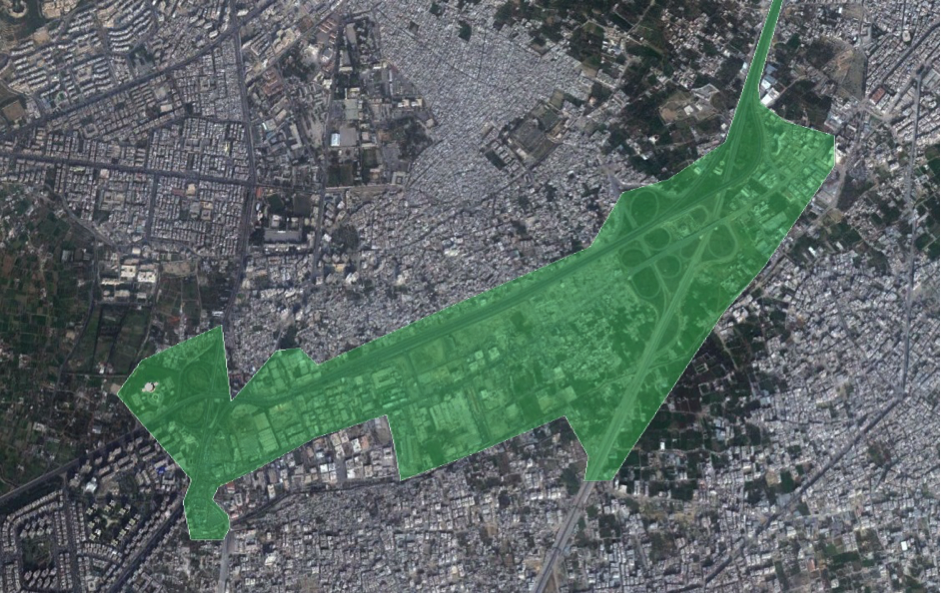

In the months preceding the August 21st Sarin attacks the Russian language news channel ANNA News had been embedded with Syrian government forces taking part in Operation Al-Qaboun.

ANNA News has produced hours of unique footage from the government side of the conflict, attaching cameras to tank turrets to give a unique perspective of the conflict. In the case of Operation Al-Qaboun they produced over 20 videos of the operation, showing its progress from June to mid-August 2013.

Operation Al-Qaboun was significant because it involved capturing a strip of territory between opposition controlled Jobar and Qaboun, with the overall aim of encircling those areas, cutting them off from other opposition held locations. This territory was only a few kilometres away from the areas attacked on August 21st, so who controlled what on August 21st was of key importance to the debate over who was responsible for the attacks.

Using ANNA News’ videos it was possible to geolocate every part of Operation Al-Qaboun that was filmed, a process covered in more detail here. It clearly showed the progress of government forces over the two month operation; which buildings and locations were captured, considered safe and targeted for attack. By the middle of August 2013, a significant area had been captured and the first stage of Operation Al-Qaboun was declared complete.

The second stage, pushing out from the newly captured strip of land, began on the morning of August 21st 2013 as the chemical attacks were occurring only a couple of kilometres away, supported by conventional artillery attacks throughout the day.

The ANNA News videos were only part of the information used to establish the areas of control on August 21st 2013. Videos posted by Syrian opposition groups in the area showed them attacking government controlled checkpoints with very sporadic artillery and mortar attacks, both before and after August 21st and it was possible to establish the exact location of these checkpoints, again using geolocation.

By combing the ANNA News videos and Syrian opposition videos it was possible to create the following map showing the area controlled by government forces on August 21st.

In addition to this information, Google Earth satellite imagery of the area from August 24th 2013 was added to Google Earth in late 2014, and examination of this imagery showed tanks and other vehicles positioned and operating in key positions and government checkpoints in this area, further confirming that the area was under government control.

When compared to a map published by the US government there’s a clear difference between the positions identified using open source investigation, and the positions marked on the US map.

The two coloured areas are marked on the US map as being “contested” and “opposition dominant”, but the unmarked area just above that, with the road running west to east through the middle of it, is the same area where open source investigation of the ANNA News videos and opposition videos from the area confirmed government forces were in control. This is particularly interesting in light of the claims from the US government that they knew where the rockets were launched from.

Having established the closest area of government control, the next question was the specific impact sites. Local groups had provided information about 10 to 13 impact sites but it was important to verify the exact impact locations.

Many of the Volcano rockets had been filmed and it was possible to establish the exact impact site of five of these rockets (three examples here). It was not only possible to find the exact locations but in three cases we could identify the approximate point of origin, which pointed north, to the east side of the area controlled by government forces identified above.

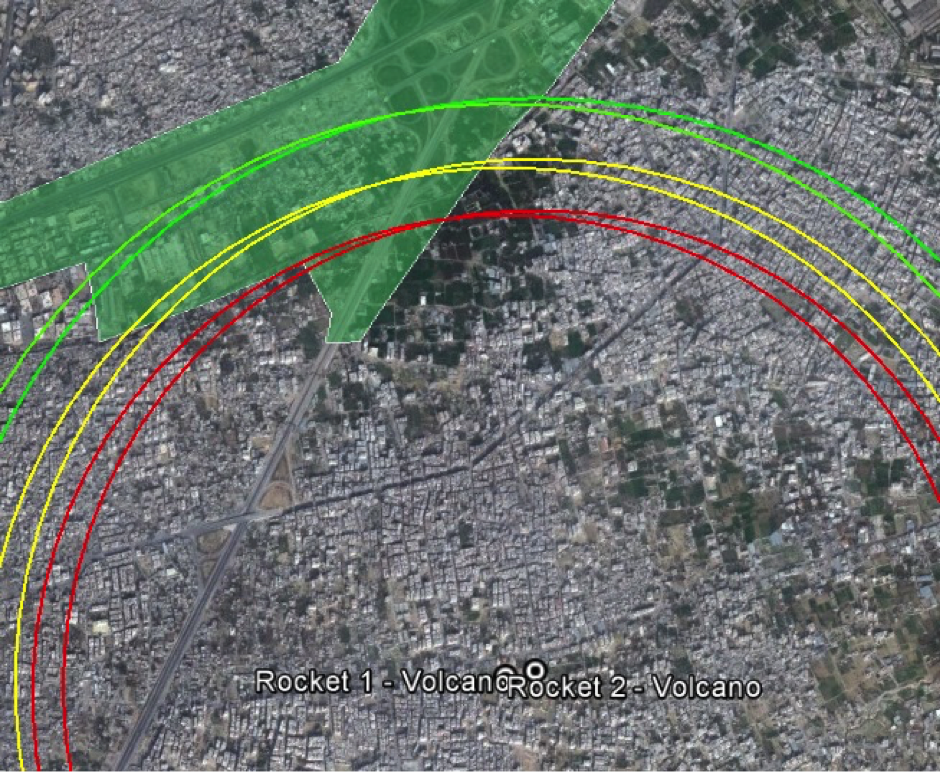

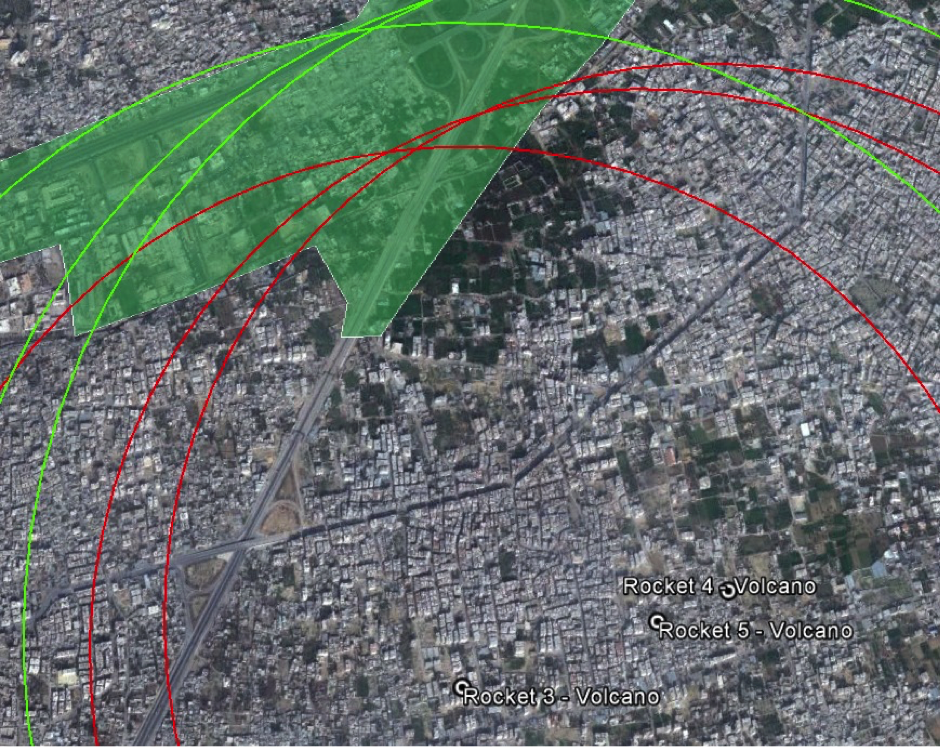

By this point two researchers had established the range of the rocket to be “about 2 to 2.5 kilometres”, and the following map shows the geolocated positions of two Volcano rockets, with the red circle indicating the 2km range, yellow 2.25km, and green 2.5km.

These rockets were the two examples that fell furthest away from the government controlled area to the north, and the impact sites suggested they had originated from that direction. Three more rockets that were precisely geolocated are shown below, with red indicating a 2km distance, and green a 2.5km distance.

It’s clear from the above images that the rockets were well within range to have been launched from the government held area to the north, even with the more conservative 2km range, and certainly with the 2.5km range.

Conclusions

Using open-source evidence alone it was possible to establish the following:

- The types of munitions used in the attacks

- That both types of munitions were used by Syrian government forces

- That the Volcano rockets were unique to the Syrian military’s arsenal

- The likely range of the Volcano rockets

- The likely chemical agent (Sarin) used in the attack

- Areas controlled by the government forces on August 21st in the east of Damascus

- The exact impact sites of several Volcano rockets in the east of Damascus

- That those impact sites were in range of government positions

Open-source investigation provides a compelling case that Syrian government forces were responsible for the August 21st 2013 Sarin attacks in Damascus, and also clearly counters many of the attempts to blame other groups for the attacks.

More information on the August 21st 2013 Sarin attacks can be found in the following articles:

The Chemical Fingerprint of Assad’s War Crimes

Facts That Have Entered the Public Domain About Sarin, Syria, and Hexamine

It’s clear that Turkey was not involved in the chemical attack on Syria

Volcanoes in Damascus

August 21st — The Rebels Did It!