Conspiracy theories have simmered on the fringes of society for years. But in 2020 they found new audiences: Celebrity chef Pete Evans welcomed foodies to vaccine conspiracy theories in Australia, while UK health care workers started anti-vaccine Facebook Groups where some falsely claimed the Covid-19 vaccine was “poison.” Anti-5G figures including British conspiracy theorist David Icke became household names as people vandalized phone masts across Europe; yoga influencers and suburban women in the US adopted QAnon beliefs and wellness bloggers made them pretty in pastels.

The pandemic created the ideal framework for mass distrust of institutions, thrusting these years-old, baseless beliefs into the mainstream. According to studies and surveys, a significant number of people globally found a tidy home in conspiracy theories promising to connect the dots between 2020’s turbulent events and their lives.

How did people become exposed?

The channels for fringe theories and misinformation were already in action on social media as millions entered lockdown measures at the start of 2020. But the nature of the digital communication landscape, evolving strategies from conspiracy theory supporters, and the additional time spent online while in lockdown helped content challenging evidence-based views reach ordinary people on a whole new level.

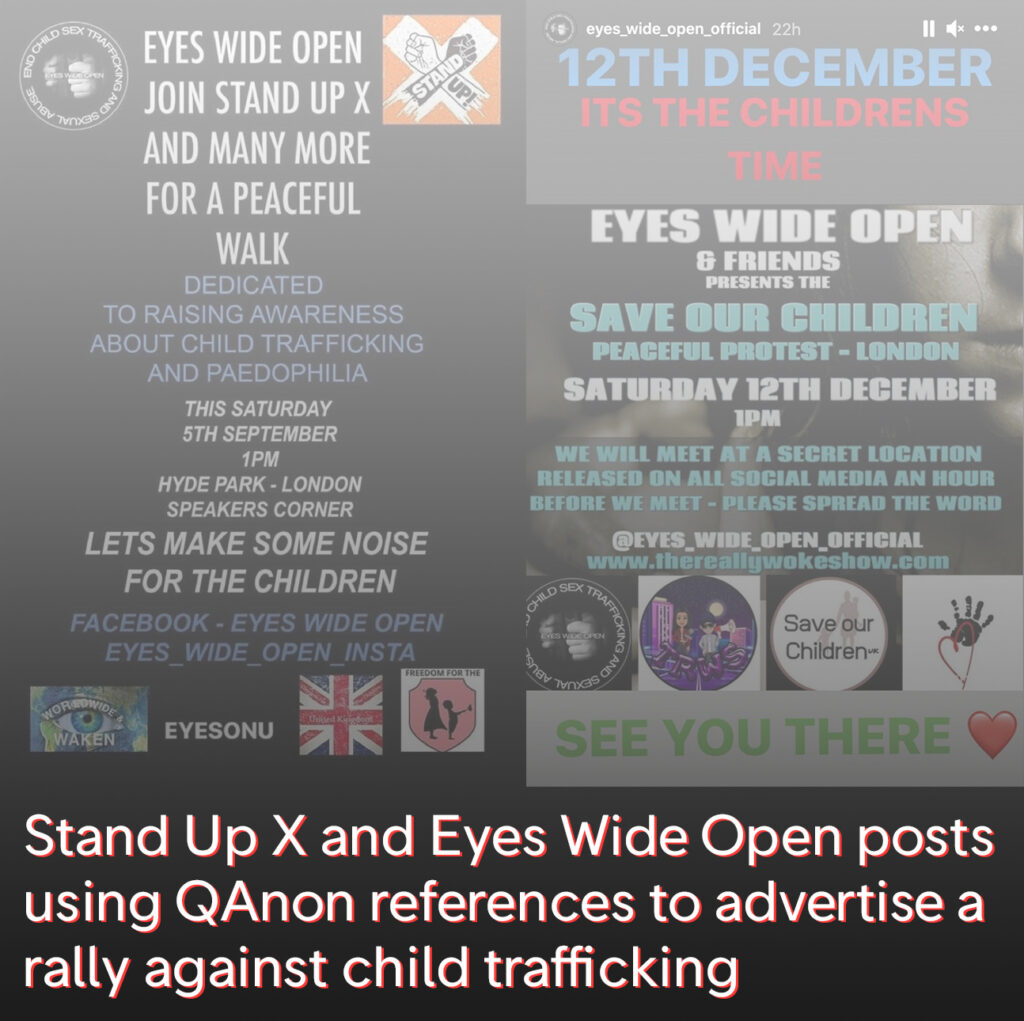

With a simple click, friends could invite each other to join any of a growing number of online spaces opposing government restrictions, such as the Yellow Vest protest groups in France and Ireland, and anti-lockdown group Stand Up X in the UK. There, people were eventually exposed to further unfounded (and sometimes increasingly extreme) ideas, such as when Stand Up X partnered with conspiracy theory outlet Eyes Wide Open UK to organize nationwide rallies promoting QAnon-linked beliefs. Some spaces grew exponentially: Facebook Group “Stop 5G UK,” created in 2017, gained more than 28,000 followers between March and April, taking its membership to more than 56,600 before it was banned by the platform.

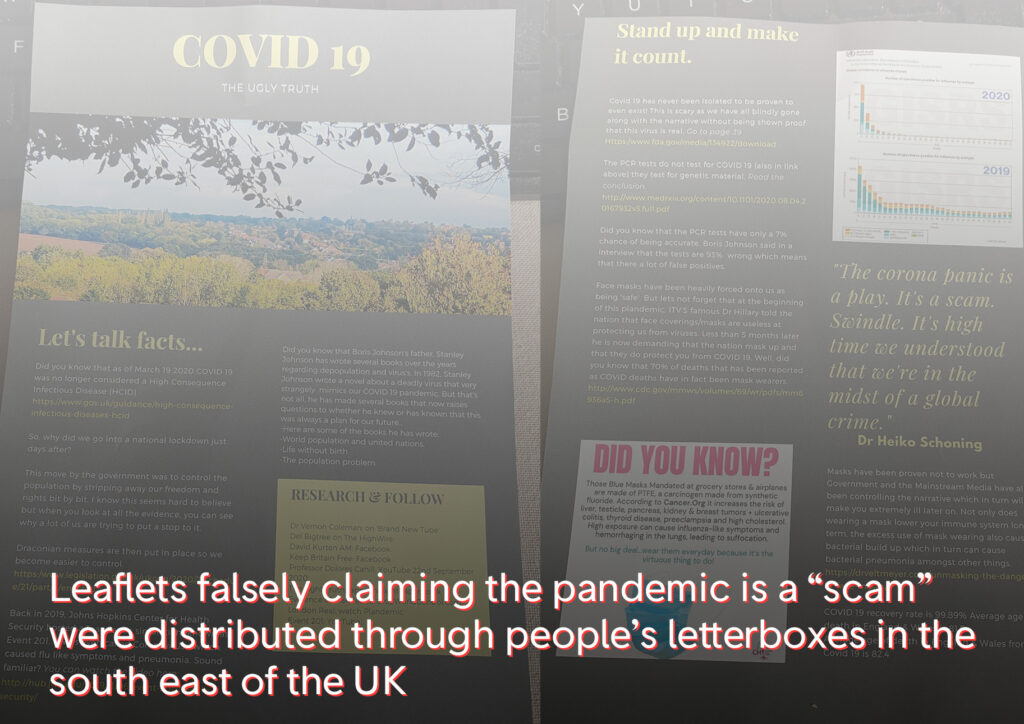

As platforms began to take action against some of these groups, conspiracy theory communities adapted to bans by creating channels on alternative networks, such as Telegram and Parler, advertising such spaces to users ahead of anticipated deletions. The network of conspiracy theories coalescing under the QAnon banner proved particularly skilled at evading moderation while recruiting members, infiltrating established anti-trafficking groups, adopting the agreeable slogan “save our children” and taking QAnon offline through rallies across the globe. Other conspiracy theorists sidestepped moderation by publishing newspapers and leaflets, reaching new audiences on a physical, local level.

Why are people susceptible?

Even before the pandemic hit, researchers had found that situations of anxiety, uncertainty and loss of control make people more susceptible to believing conspiracy theories — they provide answers and relief, while those usually drawn to them tend to be relatively untrusting and concerned for their personal safety. The threat of a deadly disease, fast-changing science and decreased mobility, however, made these attitudes more widespread, with more people probing for explanations as to why this was happening. As governments fumbled their coronavirus responses and trust in them diminished, conspiratorial outlets promising neatly packed explanations also became more enticing.

Searching for answers in times of great confusion and grief can send people down dark rabbit holes, as experienced by Dannagal Young, a social psychologist who turned to conspiracy theories after her husband’s terminal diagnosis. “These feelings of collective uncertainty, powerlessness, and negativity likely account for the popularity of Covid-related conspiracy theories circulating online,” she wrote.

Within ambiguous and terrible events, conspiracy theories increase perceptions of control by providing a channel for anger or fear, said Young. Psychologists have found that feelings of anger are likely to be followed by confidence and urges to take action. In the pandemic, creating an anti-mask Facebook Group, taking to the streets to protest or attacking phone masts may have been affirming reactions.

Increased social isolation, alienation and loneliness have also been key factors; several studies suggest links among conspiracy theories, social exclusion and ostracism. More time spent on social media globally meant internet users were more likely to find and fall into digital rabbit holes. One demonstrator at a QAnon rally in Minnesota told CNN reporter Donie O’Sullivan that she had more time to be on social media and “research” QAnon during lockdown — leaving her an ardent believer in the conspiracy theory.

Those who have suffered the worst financial losses during the pandemic may be more vulnerable — a University of Kent study suggested disadvantaged populations are more likely to find conspiracy beliefs appealing.

What next?

Conspiracy theories are often partisan, feeding from and into people’s political leanings. But they can also shape people’s outlooks and affect relationships. Reporting throughout the pandemic has shown how these theories have divided families. BBC disinformation reporter Marianna Spring documented how conspiracy theories broke up Sebastian Shemirani’s relationship with his mother, Kate Shemirani, a prominent British conspiracy theorist. Since she skyrocketed to notoriety on the coattails of the pandemic, Sebastian said his mother was “too far gone” to be able to repair their relationship.

It’s no coincidence that the conspiracy theories reaching new heights during the pandemic contain common themes around institutions and elites. They are built on similar grounds, with plenty encompassing old, antisemitic tropes.

Conspiracy theories are no longer neatly siloed ideas, as multiple theories coalesce into one worldview. What has developed is something more akin to a conspiracy theory mindset, in which people choose from a buffet of false ideas. Anyone, from a nurse to your hairdresser, is vulnerable.

With Covid-19 vaccines, potential mutations of the coronavirus, further economic fragility and US president-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration ahead, 2021 will provide more fodder for the networks of conspiracy theories that have expanded and merged this year. Journalists and researchers need to fill data deficits faster and consider how they can better connect factual information with audiences. Platforms should refine their approaches to countering the evolving tactics of conspiracy theorists — banning harmful groups long after they’ve already proliferated is not enough. Conspiracy theories should no longer be viewed as isolated strands — they need to be treated as an interconnected web of ideas. Otherwise, they will continue to promise a tempting nest full of answers for those asking questions.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.