The horrors of war have been a mainstay of journalism for as long as the industry has existed, but the rise of smartphones and social media have fundamentally changed how it is reported.

When anyone can film a massacre, a violent death or a bombing and upload it to the internet within minutes, newsrooms become inundated with graphic imagery to filter and verify before considering whether it should be published. This constant barrage of grief and gore is taking an increasing toll on those charged with reviewing it, in the form of vicarious trauma.

At the tenth International Journalism Festival in Perugia, a panel of experts in vicarious trauma gathered to discuss the phenomenon and possible solutions.

In the first few months of the Arab Spring, Reportedly’s managing editor Andy Carvin would watch such videos in “a very solemn fashion”, he said, turning off any music, asking colleagues to stop talking and treating them with a fitting sense of gravitas.

“But after watching hundreds I became the proverbial TV detective standing over a body eating a sandwich,” said Carvin. “I was blasting music while watching videos, joking with colleagues.

“It was only six months later I realised I had a problem.”

Food became a trigger for memories of graphic images and scenes. Seemingly harmless vegetables would be reminders of body parts. Even the smell of cooking would send his heart racing, the body going into defense mode before the brain realises what is happening, and why.

“I’d go to a salad bar, see a bowl of cauliflower and practically run out of the restaurant,” he said.

Anyone who has stumbled over a horrific image or video of war will recognise the symptoms: the stunned feeling of shock, the swift release of adrenaline and tightening of muscles.

The body’s natural, biological defense mechanisms developed millions of years before the advent of cameras and social media, so the reptilian brain is the first to react to extreme images of violence before our conscious mind can process the footage. On a basic level, the body doesn’t know the difference between someone burning alive on a screen or in the room with us. It still happens right in front of our eyes.

“The brain gets overloaded by a stressful situation that threatens death or serious injury,” said Gavin Rees, director of the Dart Center Europe, “and the body goes through a process of stress response.

“When people get PTSD, the body doesn’t reset and it stays stuck in alarm mode.”

A lot of people are exposed to trauma and lots of people have a difficult experience with it, he said, but only a small number develop a serious problem like PTSD. Knowing the risks, warning signs and coping mechanisms can be the difference.

Watch the full panel discussion, chaired by Sue Llewellyn

Eyewitness Media Hub released a report in December to investigate the impact of traumatic imagery in newsrooms, speaking to editors, managers and individual journalists.

Over 90 per cent of journalists who responded viewed eyewitness media once a week. More than half said they viewed distressing footage several times a week. Forty per cent said it had a negative impact on their personal lives. Even those who had made a conscious decision to work from the newsroom and not be on the frontline are now seeing the same footage as their colleagues in the field.

“Twenty years ago you’d get one or two agency feeds, shot by a professional 15 minutes after the event,” said Sam Dubberley, who lead the research as co-founder of EMHub. “So it was pre-edited.

“Now you see it as it happens, shot from seven or eight angles and you see the whole traumatic event.”

Respondents shared some of their coping mechanisms and practices to limit the impact: turning off the sound, making the viewing window smaller, only watching the necessary parts of the video, not surprising colleagues with graphic images and making sure to limit exposure whenever possible.

Age and experience can also be a factor in individuals coping better with viewing graphic imagery, but through the research Dubberley found that young journalists were often more exposed. Only 30 per cent of journalists surveyed who said they had been affected said they would speak to their superiors about the issue.

“One person, it really got to them, looking at constant bombings from Syria, kids maimed and injured,” said one respondent in the report. “They’d probably clicked on too many grim things and they couldn’t move from their desk, they were in shock. I literally had to peel them away.

“One of the things was that they didn’t want management to know because they thought that would be it. That they would never be given the opportunity again.”

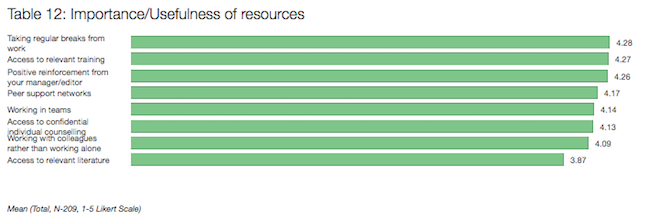

Social suport, relevant training and regular breaks are some of the most important factors in helping journalists cope with viewing traumatic images. Screenshot: EMHub

“This needs to be a top-down initiative to address vicarious trauma in the newsroom,” said Dubberley. Journalists in the field get hostile environment training, but currently very little exists for those dealing with trauma in the newsroom.

At the BBC, all new employees are made aware of the issues and managers are briefed on the potential for mental health issues among journalists. Trauma awareness training has brought a “huge jump” in people coming forward and asking for help, said Kate Riley, who manages trauma-related training for the broadcaster.

“Training or awareness often takes the form of lunchtime briefings,” she said, “and a lot of it is just about people talking to each other.”

Reportedly has a team of six who largely work from home, in isolation, making communication between the team of vital importance to make sure individuals are dealing with what they are seeing.

“Sometimes I’ll switch a staff member to the cat video beat for a day,” said Carvin. “And we have a slack channel where we share cat videos regularly.”

It may seem trivial, but respondents to the EMHub survey reported similar coping mechanisms: looking for cute dogs on Tumblr or watching Taylor Swift videos.

“Every journalist working with graphic images needs some kind of self-care plan,” said Rees, “irrespective of what the organisation does.”

The key thought for Rees, though, is that distress is a natural response to traumatic images and only a small number of people develop anything as serious as PTSD. But if exposure to such images is not properly managed, the risk of serious repercussions become greater.

The Dart Center has advice for journalists working with graphic footage and EMHub’s report includes recommendations for journalists and managers who work in the area.

Carvin has started a Facebook group for journalists to discuss the issue of trauma and coping mechanisms, as one of the most important factors in coping is social support. Regaining a degree of control over how and when graphic images are viewed, and having a handle on limiting the impact, is crucial as well.

“If you create a culture among journalists in which it’s ok to talk – not forcing people to talk but breaking down that sense of isolation which is very toxic – then it gives back a sense of control,” said Rees.

Read more about vicarious trauma and how to deal with it in the First Draft section on Ethics and Law.