This article is part of a series on health misinformation.

Dengue is a viral infection found in tropical and sub-tropical climates, and is currently the most rapidly spreading mosquito-borne viral disease in the world. In April 2016, Dengvaxia, a vaccine created to help prevent dengue fever was introduced in the Philippines and administered to over 800,000 children through a school-based campaign. By 2018, the Philippine government stopped the campaign due to controversy around how the vaccine affected people who had never had the disease.

What followed was a flurry of online misinformation, with influential bloggers and the national media amplifying the panic, and a highly politicised investigation. In the midst of this crisis, trust in vaccines’ safety plummeted from 82 percent in 2015 to just 21 percent, and may have contributed to a recent spike in polio and measles in the Philippines.

Dr. Lulu Bravo, Professor of Pediatric Infectious and Tropical Diseases at the College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, explained that the crisis marked a turning point for vaccine hesitancy in the country.

“After Dengvaxia all hell broke loose. Mothers were driving away health workers when they came to villages on immunisation campaigns, calling them child killers. This has never happened here before.”

A First Draft study has examined how online misinformation about the Dengvaxia controversy exacerbated vaccine hesitancy. The case study highlights key elements that often form the backbone of information disorder, and particularly health misinformation.

Read the full study: Exploring the controversy around Dengvaxia and vaccine misinformation in the Philippines

It found how a small basis in reality became wrapped in unsupported figures and a highly emotional, politicised narrative. When this was amplified by social and mainstream media, the misinformation created a crisis the country is still recovering from.

Kernel of truth

As with many pieces of misinformation and conspiracy theories, there was often a kernel of truth at the centre of the lies.

In late 2017, the pharmaceutical company behind Dengvaxia, Sanofi Pasteur, published its official review. It found that in rare cases, Dengvaxia could pose an increased risk of severe dengue illness for people who had never had the disease, so-called seronegative patients, if they contracted the virus after being vaccinated.

As dengue is endemic in the Philippines, the risk of this side effect impacts about 15 percent of vaccinated individuals. Of this seronegative 15 percent (those who have never had dengue), only around four in 1,000 patients vaccinated were found to have developed severe dengue disease within five years of observation.

Shortly after Sanofi released their report, the World Health Organisation (WHO) advised that Dengvaxia only be used in people previously infected with dengue. It was this report and subsequent action formed the core of the fears around Dengvaxia.

Seronegative subjects refers to people who had not been exposed to the dengue virus infection prior to vaccination with Dengvaxia

“Often with health misinformation, it’s taking something that is a very small, manageable risk and turning that into an alarmist conspiracy,” said Craig Silverman, BuzzFeed media editor and a leading disinformation expert.

“In general, the average person doesn’t really have a good understanding of how relative medical risk compares to all the risky things we do in our daily lives. If all you talk about is the risk, then you misrepresent the likelihood of it affecting people.

“That can have a very powerful message,” he added. “You can really scare the hell out of people.”

Politicisation

The Department of Health (DoH) suspended the vaccination programme in December 2017, almost immediately after the WHO’s ruling, and the Philippines revoked Sanofi’s product licence for Dengvaxia in February 2019.

Soon after, the Department of Justice claimed to have found probable cause to indict officials from Sanofi, alongside Philippine health officials, over ten deaths it alleged were linked to use of the dengue vaccine.

The controversy triggered two congressional inquiries and a criminal investigation.

Dr. Rabindra Abeyasinghe, WHO representative in the Philippines, pointed to political motivations as important to understanding the Dengvaxia controversy.

“The Dengvaxia pilot was decided and implemented by the previous administration,” he told First Draft. “When governments change, usually they’re looking for issues that they can blame on previous governments.

“When Sanofi came up with new evidence and came out with a new recommendation, this became an issue that was used by different political factions for their own ends.”

If the policy U-turn seemed to confirm parents’ fears, the highly politicised and televised investigation that followed only made matters worse. Research by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine suggests this politicised response was the primary reason for increased vaccine hesitancy and public mistrust.

Rather than addressing questions of the vaccine’s safety, and thus placating parents’ concerns, the drawn-out Senate investigation instead focused on corruption allegations. The information vacuum this created led to conspiracy theories that the government had received financial kickbacks while putting children’s lives at risk.

Unsubstantiated figures

The investigation gave the Philippines’ Public Attorney’s Office (PAO) a platform from which to launch an uncorroborated campaign against the DoH.

Speaking to First Draft, Dr. Heidi Larson, director of the Vaccine Confidence Project at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, said there was insufficient evidence to causally link deaths in the Philippines to Dengvaxia.

Edsel Salvana, the Director at the Institute of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, National Institutes of Health University of the Philippines Manila, explained: “There is not a single case of death with a causal link to Dengvaxia that I am aware of. You would need to recover the vaccine chimeric virus to prove that and as far as I know, none of the cases established that or even checked for it.”

This is in direct contrast with the unsubstantiated figures publicised by the PAO, which reported in February 2017 that more than 8,400 people had become sick and more than 130 had died after receiving the Dengvaxia vaccine.

The PAO used a team of investigators who were strongly criticised by the Philippine medical community as being unqualified in the necessary forensic fields to compile the evidence. The team performed autopsies of childrens’ bodies on live television, further sensationalising the incident.

People display signs and a mock syringe, with the phrase “3.5 billion pesos Dengvaxia fund investigate” featured on it, during a protest in front of the Philippine Department of Health (DOH) in metro Manila, Philippines December 5, 2017. The poster (L) reads: “Sanofi and DOH should be held accountable”. REUTERS/Romeo Ranoco

Emotional response

The crusade against the vaccine tapped into an emotion inherent to vaccine hesitancy: fear. Disinformation is often designed to trigger a strong emotional response, and health — particularly children’s health — is fertile territory for exactly that.

“Health misinformation is powerful because health has a very real effect on people’s lives,” Silverman underlined. “That creates an opportunity to spread false or misleading information that people can have a really strong emotional reaction to.”

The mainstream and social media campaign against Dengvaxia played on this emotional impact, using sensationalist headlines and memes to attack the DoH and attract an audience.

Dr. Bravo attributes blame for the rise in vaccine hesitancy to the PAO’s campaign against Dengvaxia, but also to the mainstream media for amplifying misinformation.

“[The public] were getting their information mostly from radio and television.

“Popular radio hosts were putting out disinformation saying kids died after being injected with the vaccine, with mothers on air crying and cursing the government. Then they’d have someone on from the PAO saying there’s a pattern [linking deaths to the vaccine].

“Every day they’d be counting deaths, saying ‘here comes another death from Dengvaxia’. Every day [parents] would be hearing that… How could you not get scared?”

Media amplification

Alongside platforming the PAO’s relentless campaign against the DoH, outlets often led with sensationalist headlines reporting false claims about Dengvaxia deaths and stories suggesting wide-scale corruption and cover-ups.

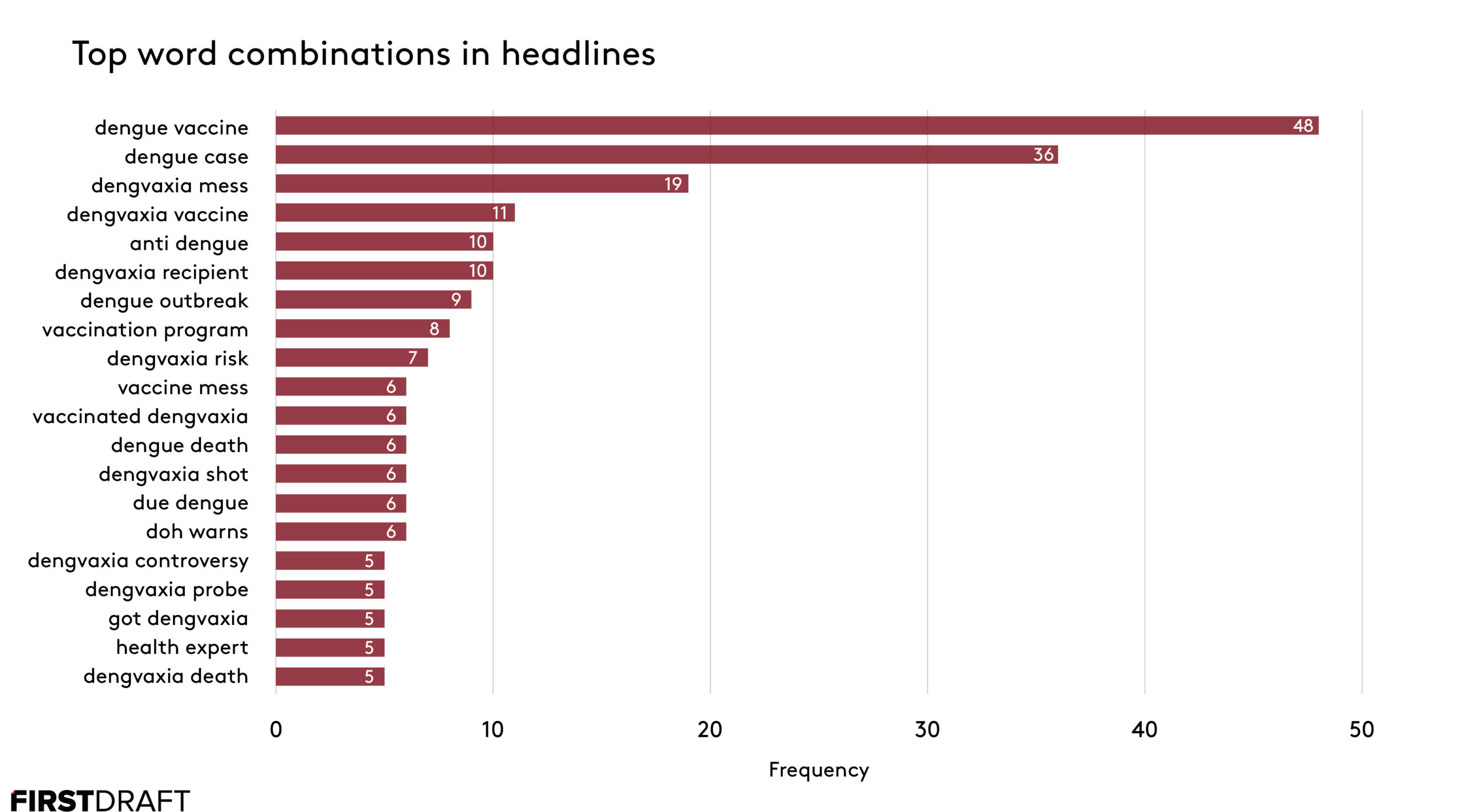

First Draft’s language analysis of 427 English language headlines published during the height of the panic around Dengvaxia supports the theory that the media fueled hysteria and conspiracy theories, with inflammatory phrases like “Dengvaxia mess,” “vaccine mess” and “dengue death” featuring prominently.

Word combinations in headlines promoted the idea that the government had bungled the vaccination programme.

Outlets also published emotive videos, including footage widely shared across social media of children allegedly dying because of the Dengvaxia vaccine.

As underlined by Washington Post reporter Valerie Strauss in a recent article, health misinformation has special potential for spreading through visual content, as images and videos of people suffering from medical conditions are some of the easiest to shift to false contexts.

Acosta’s campaign against Dengvaxia was supported by multiple Facebook Pages, such as Friends of the Public Attorney’s Office – PAO and United Dengvaxia Victims. The pages shared misleading and unverified content, including the hotly disputed forensic findings.

First Draft’s analysis found a series of memes amplifying the unsubstantiated death tolls and the qualitative research found a handful of popular Philippine bloggers were responsible for creating and sharing most of the conspiratorial content across both Facebook and Twitter.

Platforms’ responsibility

The widespread use of Facebook and Twitter to share misleading information about vaccines raises questions of the platforms’ roles in hosting this content. Considering the responsibility of platforms in monitoring vaccine misinformation, Silverman said:

“You can have a vaccine that has decades of the best possible medical evidence we have [and there’s still misinformation online about it]. If the platforms aren’t willing to act in these cases, then what are we going to do in other cases where there’s more of a grey area?

“The platforms are hesitant to really come in and set down some hard and fast rules, but I think it’s starting to change a bit.

“When children die because their parents won’t vaccinate them, there is a huge amount of outcry and pressure on platforms to do more to get rid of vaccine misinformation.”

Transparency

Alongside social media companies taking a more stringent approach to misinformation, Silverman stressed the importance of clear and honest information in countering vaccine hesitancy.

“You have to think about ways of communicating the relative and minor risk to the public in a way that seems very transparent and honest,” he said.

“You have to find really effective ways of painting the picture of how it compares to other things people do in their daily lives, for example, riding a motorcycle.

“It takes a big public health communication campaign to counter this stuff. And it takes demonstrative evidence, like having parents who have given their child a vaccine talk about it publicly.

“It’s not enough to just say that people are misrepresenting [vaccines]. You have to think about how you reinforce the positive aspects of it as well. Pure debunking isn’t going to be enough.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by subscribing to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.