By Alastair Reid

With the number of both smartphones and social media accounts outnumbering the global population, eyewitness media is only going to play an increasing role in journalism. True, cats and sarcasm are the internet’s stock in trade, but as modern technology reaches the more desperate regions of the Earth, so are the horrors of war beamed into cosy urban newsrooms, far removed from the physical reality of conflict.

A central societal function of a news organisation is in being a filter of such news for the public, balancing the need to supply important information about the world without turning them away with its full kaleidoscope of horrors.

“One of the major issues is the distance between management and people on the shop floor,” said Sam Dubberley of Eyewitness Media Hub (EMHub), presenting some preliminary findings from research into vicarious trauma at last week’s News Xchange conference in Berlin.

According to the research, 58 per cent of journalists who work with social media and user-generated content (UGC) see something traumatic at least once a week, a figure that drops to 46 per cent for editors and is significantly lower for senior managers.

“It’s important to recognise that the frontline has shifted to include the warzone and the newsroom,” said Dubberley. In the past, a cameraman might get to the scene of a bombing after the event had happened, shoot five minutes of footage with the professional discretion before sending it to an editor. That editor would then edit the footage for public consumption before it reached a wider audience.

The same type of footage is now being captured by members of public as the horror unfolds. They upload it to social media where it is intercepted by journalists, many of whom are young and inexperienced, placed on the social media desk for their digital skills.

Sam Dubberley/EMHub

Eleven per cent of journalists working with UGC saw traumatic images every day. For editors that figure is slightly higher, according to the research, at 13 per cent.

“The best thing to do is to conceive of this kind of traumatic imagery as radiation,” said the Dart Center’s Gavin Rees, speaking at the same event. “We have to work with this stuff, but what can we do to limit the exposure.

“We have to find work arounds that mean we’re putting this stuff in a place that is not generally available in the newsroom. So people have some kind of training and understanding of what this material is, how to look after themselves and how to manage others in situations.”

“You witness trauma a lot more with UGC,” said one senior editor in the course of the research. “You’re exposed to more intense visual material than a battle hardened war cameramen sitting in Sarajevo in the middle of the 1990s because it’s coming at you from everywhere.”

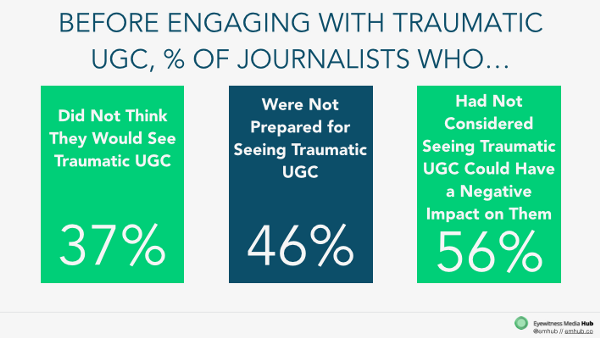

Surprise is one of the biggest contributing factors to distress from traumatic imagery, so it is important to recognise the dangers and allow journalists to ready themselves for what they might see — whether it is from Twitter, YouTube, Facebook or, increasingly, closed networks like WhatsApp.

“[Respondents] were able to deal with it better if they were ready for it,” said Dubberley. “If they are not ready for it, it’s a lot harder.”

The body’s defense mechanism’s react faster than the consciousness, explained Rees, giving the body an adrenaline rush before it can process what it is seeing. Without putting the psychological guards up to soften the blow of traumatic images, the impact of shock can be much stronger.

This is a universal reaction, continued Rees, so it does not mean that someone is “soft” or unable to do their job. The spectrum between bouncing happily into work and full blown post-traumatic stress disorder is wide and varied, and de-escalating distress may be as simple as taking a break.

What is important though, he said, is that newsrooms and managers are aware of the potential impact and de-stigmatise the effects. Letting distress grow without an outlet, without talking about it or stepping away from it, can lead to more serious consequences.

While a counselling hotline is a good first step, the goal is to not let journalists feel the need to make the call in the first place, and a lot of the time that comes down to the newsroom culture, said Dubberley.

“Of all the psychological things you can have wrong with you, PTSD is about the easiest thing to treat,” said Rees. “The problem we have treating journalism organisations is that people don’t know that and they are scared of seeking help.”

“Some organisations are really good with scheduling and how they put producers on rotation,” said Dubberley. “In a newsroom with two social media editors, the standard pattern is one week of hard news and one week of soft news. And that really helps.”

Again, the point is in having managers or editors aware of what their staff may be putting themselves through to report the news, and limiting the possible negative affects as much as possible.

“People who develop trauma trouble often get very angry and feel that no one understands,” said Rees. “They get intensely irritated and have memory lapses. You can see how that’s a career threatening thing. Not having a proper trauma management policy in place can cost a lot of money.”

Quote from a respondent in the EMHub study on vicarious trauma. Sam Dubberley/EMHub

With a far greater body of traumatic evidence to support the news than in previous years, the imagery needs to be archived in a way that is not going to impact journalists in the future, said Dubberley.

“When you’re putting content in your server, think about the whole workflow in the newsroom chain,” he said. “Not just the journalist or producer, make sure it’s labelled as graphic with a warning to not look at it unless you really have to.

“Think about how it goes on your server and how it travels around the newsroom, don’t just put it in there.”

Doing so could expose colleagues to a shock dose of horror that could ruin their day, and their productivity as a result.

A stressful or toxic working environment can compound the issue of trauma, said Rees, because it feels like the social fabric, so important in helping people feel settled and safe, is broken everywhere.

So being supportive of colleagues working with traumatic imagery, and a management looking to maintain a positive culture in the newsroom, can go a long way in limiting the impact of traumatic footage.

“It has to be owned by the newsroom,” said Rees. “We are strong through our understanding of each other. A tap on the shoulder of someone who seems a bit spaced out, more in Iraq than in London, to say ‘I’m having a break do you want a copy? Want to get some air?’ [can be really helpful.

“The sense that people are being helped is the most protective thing.”

When thinking about traumatic images like a dose of radiation, it makes sense to limit the exposure as much as is practical. This can come in the form of schedules which are more aware of the issues or just managing your own time properly.

One respondent to the EMHub survey cited dog Tumblrs and Taylor Swift’s Instagram as places they go online to de-stress in between checking pictures from Iraq or Syria.

It is important for editors and managers to be aware of this habit as well, and to be open with superiors if this is a chosen practice. Most reporters shouldn’t really be playing BuzzFeed quizzes at work, for example, but it is more understandable if they spent the last 50 minutes looking at body parts and the after effects of a barrel bomb explosion.

The audio accompanying a horrific video can double down on the traumatic impact, but it sometimes it is not necessary to verify a video.

“If I have to listen to someone begging for their life, that I can’t cope with,” said one delegate to the session. “If it’s just the images, then I can deal with the editing process. That’s one of my little ways of coping with the horror of what is out there.”

Sometimes it is necessary to check the audio for languages or local dialects to help in verification, but that doesn’t mean the sound is necessary all the time. Screams and gunshots are regularly cited as some of the most traumatic aspects of conflict footage, especially when the rest of the newsroom is getting on with their day unaware.

Just as limiting the sound can help, as can limiting the images. Making the browser or video window smaller is one method, but if looking at an image in detail, to check road signs or landmarks for example, distressing parts of the image can be covered with a sticky note or piece of paper.

If graphic images become a regular part of the week, it can be important not to have repeat exposes of similar imagery outside of work. Many delegates and respondents noted that they didn’t feel able to watch violent television shows or films after experiencing trauma but only after making the mistake of doing so in the first place.

Psycholgical preparation can be one of the biggest protectors against lasting impact of trauma, said Rees, and every journalist working with eyewitness media should develop a self-care plan to make sure they are aware of the dangers and how they will cope.

The Dart Center has more advice for journalists working with graphic images and the central points for self care.