By Josh Stearns

People intentionally spread misinformation and fake eyewitness media online during breaking news for an array of reasons. For some it is an experiment, to see how far and fast their lies can spread. For some it is an act of propaganda, using the moment to draw attention to an issue they care about, or to make a political point. For others it is a joke, the digital age equivalent of prank phone calls.

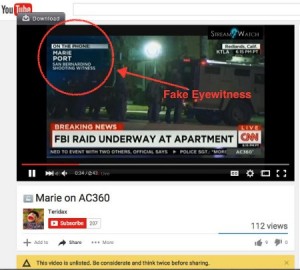

But increasingly, we have seen targeted misinformation used as a form of media criticism and antagonism. That was the case during the San Bernardino shooting, when a fake eyewitness — who goes by Marie Christmas on Twitter — ended up in major stories from CNN, International Business Times and even an Associated Press piece that ran online at the New York Times.

After appearing in numerous media reports Marie Christmas tweeted “IT WAS A PRANK BRO” and “I EXPOSED the media smh.”

Screengrab by Steve Buttry

Industry veteran and director of student media at LSU’s Manship School of Communicaiton Steve Buttry has chronicled this story better than any other. His very long post on issues surrounding Marie Christmas is well worth your time. It reads like a tick-tock of how Marie Christmas and other fake Twitter accounts took advantage of a tragedy to advance their own agenda.

Interspersed within that post is a lot of wisdom about how to assess and verify eyewitnesses during breaking news. I asked Buttry if I could highlight some of the best lessons from his post. As more people are intentionally seeking to insert themselves into breaking news coverage, journalists reporting via social media have to hone their skepticism and take the time needed to fully vet online sources.

In this case, as Buttry notes, while a few big media outlets took the bait many were skeptical. We can learn from both.

Here are five ways to avoid getting duped during breaking news.

Buttry quotes Brian Ries of Mashable, who raised early concerns about the past tweets from “Marie Christmas,” calling them “troll-y.” Past tweets can give you a lot of information about a person. You can dive into this info both by simply scrolling backward through their timeline but also by doing some targeted Twitter searches for keywords.

Often Twitter bios are mundane and provide little insight, but sometimes they can raise red flags or lead you to more information. Google the person and some of the things they discuss in their tweets prior to the event:

Cross reference what eyewitnesses are saying publicly on Twitter and in follow up conversations with you with what you know about the site of the breaking news. Use Google maps and publicly available images of the surrounding area and see if they match the description of the place and events on the ground. There were two discrepancies noted in Buttry’s piece.

First Buttry himself noted that “The International Business Times, quoted “Marie Christmas,” saying she lived in ‘La Puerta, Calif.’ […] Google Maps shows a couple California businesses in the San Diego area named La Puerta, but not a community by that name. La Puente, Calif., is about 50 miles west of San Bernardino.”

Andrew Seaman, chair of the Society of Professional Journalists Ethics Committee, questioned Marie Christmas’s description of events, saying to Buttry “The area doesn’t lend itself to simply being across the street.”

Buttry talks a lot in his piece about the ethics and etiquette of reaching out to eyewitnesses during breaking news, and he includes a lot of tweets from journalists who reached out to Marie Christmas. Most wanted a phone call, and that’s a good start. As Buttry notes, “You can vet a source better and more politely over the phone.”

However, Marie Christmas said she didn’t have a phone. That was a red flag for some journalists — how was she tweeting from the scene without a phone? She said she was on wifi but wouldn’t she be moving? When CNN did get her on the phone, Seaman pointed out that she gave very little detail and talked about the gunman entering a “hospital”.

Getting on the phone isn’t always possible, but if you can’t get on the phone with someone it is all the more reason to double and triple check their story before using them as a source. Push for clarity via direct message, ask for contacts of people who can corroborate, request pictures of the scene, etc.

If this is all too much to ask of the person amidst breaking news, then it may be worth shelving that witness for the time being and following up with them when they are home later and when you can treat them with the care and empathy they deserve (assuming they really were there).

Throughout Buttry’s post many of the journalists he talked to expressed doubts and skepticism about Marie Christmas. This is a reminder that so much of verification — whether online via social media or in person around our neighborhoods — is a matter of following your gut.