By Alastair Reid

It is no secret that foreign reporting in Western media is not what it once was. Many organisations are struggling just to maintain their domestic editorial staff numbers, and a combination of government crackdowns and hostile militia make some parts of the world no-go zones, even for local reporters.

“There are so many places around the world where the foreign correspondent can’t just walk in with their white flag any more,” said Trevor Snapp, chairing a panel on the importance of eyewitnesses and citizen journalists around the world at the Frontline Club in London this week.

Fixers, bloggers and so-called citizen journalists have often become a stop-gap for news in these areas. With sources and connections built over a lifetime and the digital means to spread their reports around the world, these local contacts are often the sources for stories that would otherwise be missed.

The term ‘citizen journalist’ was dismissed by Verifeye Media founder John D McHugh, however, stating “you’re either a journalist or you’re not” and anyone who reports on events worthy of news coverage should be recognised for what they do, the risks they take and in the compensation they deserve.

Many governments are seeking to repress the ability of their citizens to report stories, however.

A 2014 report by political freedom watchdog Freedom House detailed how more than half of the 65 countries assessed had shown a tightening of laws governing online communication between May 2013 and May 2014. Russia, Turkey and Ukraine had shown the steepest decline, while Iran, Syria and China were the “world’s worst abusers of internet freedom overall”. Social media users were identified as one of the main targets for arrest, particularly in the Middle East and North Arica. Online journalists and bloggers were arrested in more than a third of countries assessed, and in almost two thirds of Sub-Saharan African countries.

These countries and regions are among the highest on the international news agenda and the people who live these stories are more valuable than ever in being able to cover them. Getting access to areas and communities which journalists from other countries can only hope to reach is possible with digital communications and lightweight cameras, but it should not be taken for granted.

“If eyewitness media is not treated properly, if the people who create it are not treated properly, it will retreat behind closed walls,” said McHugh, “and I think that is a result of [eyewitnesses] being treated unfairly.”

McHugh launched Verifeye Media in 2015 as a visual news agency to help news organisations cover areas they otherwise may not, and to get eyewitnesses and freelance photographers paid for their work. When users of the Verifeye camera app capture images the footage is sent directly to the company’s online editorial hub, complete with metadata for verification purposes, before McHugh and his team license the material to news organisations.

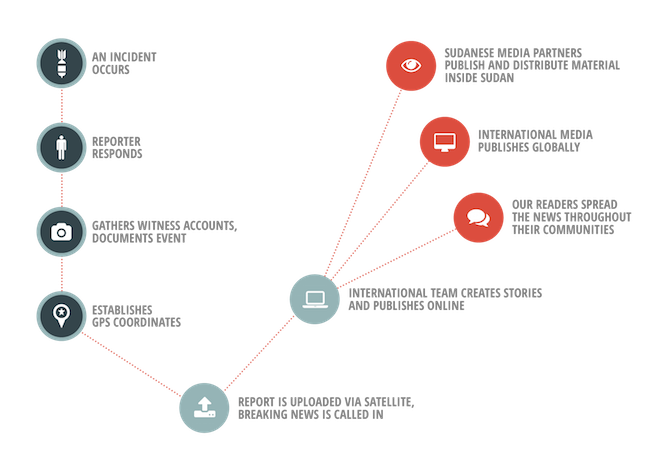

Snapp’s Nuba Reports organisation works in Southern Sudan, in an area compared to Darfur for the war crimes committed by regional and national forces. Four lead reporters head up teams of local ‘observers’ spread around the region to document bombings and tell the stories of persecuted communities.

How stories travel from the ground to international publication at Nuba Reports. Screenshot from Nuba Reports.

Although the lead reporters identities are public, their network of observers are not, and the stories of displacement and persecution have reached international news organisations around the world.

“People that are committing these kind of crimes and atrocities are getting smart to when Western media turn up,” said Jacqueline Geis, head of development and external communications at human rights charity Videre est Credere, making the need for eyewitness media in reporting such attacks all the more important. Videre gives communities the training and equipment necessary to document human rights violations in countries around the world, with a strong focus on security.

Freelance journalist Chavala Madlena has carried out similar work for the Guardian, spending nine months in Yemen building relationships and training individuals in the core concepts of journalism and filming. One such individual was 13-year old Mohammed Tuaiman, left to care for his 27 siblings after his father and brother were killed in a drone strike in 2011.

Mohammed filmed the day-to-day life of his family and village and the struggles they faced since the loss of the main breadwinners, how they “dream of drones” in an area caught between Houthi rebels, government forces and the local Al-Qaida cell. In January 2015 Mohammed, too, was killed in a drone strike.

Thirteen-year old Mohammed Tuaiman, filmed by one of his brothers, before he was killed in a drone strike. Screenshot from the Guardian.

This is the inherent risk of anyone reporting from dangerous areas, the “nightmare scenario”, said Madlena, and the reason why McHugh is so adamant about not just ensuring his contributors on Verifeye are safe, but that they also get paid.

Although he will not encourage “maniacs” who have no consideration for their own safety by licensing their work to news outlets, he insisted there are “young journalists or people who live in a story who want to tell that story and we don’t have the ability or the right to tell people what to do”.

“Journalism used to be a lecture,” he said, ” but now it’s a conversation and there are lots of conversations going on in areas that we don’t have access to.”

“It’s about working together now and not seeing each other as threats,” said Snapp. “Mainstream media organisations need these local networks” but have to conduct themselves in a respectful way to maintain the relationships.

Not every organisation has the resources to send trainers into the field, of course. But the nature of online communications, despite government crackdowns, means journalists can establish and grow networks of contacts in repressed countries in new ways. Journalists reaching out to users of the main social media networks is a regular but brief occurrence, essentially a form of digital parachute reporting, but without the requisite costs of the real thing. Without any costs attached, why not develop those relationships for future stories, or take the conversation onto private networks?

The BBC has worked hard at building sources in Iran through the encrypted chat app Telegram, for example, and many news organisations have been using WhatsApp to speak with sources directly in areas they would otherwise not be able to reach.

Building these relationships takes time, effort and a little digital nous, said McHugh, but relies on the same basic elements of trust and rapport that have underpinned journalism since its earliest years. Remote eyewitnesses providing images and information through digital means are just the latest iteration of the conversations that previously took place face to face, or on the phone. If journalists are not respectful in how they carry out these conversations, he said, they risk getting frozen out entirely.

“Eyewitness media is not the future of journalism, it’s the now,” said McHugh. “It’s happening every day on every major and minor story and we have to figure out how to utilise it to its full capacity.”

Giving eyewitnesses the same respect and consideration as other types of sources, or even other journalists, may be the only way to make sure news organisations can continue to cover the stories from around the world which matter the most.