In the closing days and hours of any election, the information environment is particularly febrile. Monday December 9, days before voters in the UK head to the polls, was both a bad day for the ruling Conservatives and an even worse day for information integrity.

It all stemmed from a story in the Daily Mirror of a four-year-old boy, Jack Williment-Barr, who was photographed lying on a hospital floor due to a lack of beds. Labour seized upon the photo, using it to underscore their argument that the Conservatives cannot be trusted with the National Health Service.

The emotional force of the photograph was a potential PR disaster for Boris Johnson’s campaign. The issue was compounded when Johnson refused to a look at a photo of young Jack presented to him by ITV journalist Joe Pike. Instead, Johnson snatched and pocketed Pike’s phone.

Tried to show @BorisJohnson the picture of Jack Williment-Barr. The 4-year-old with suspected pneumonia forced to lie on a pile of coats on the floor of a Leeds hospital.

The PM grabbed my phone and put it in his pocket: @itvcalendar | #GE19 pic.twitter.com/hv9mk4xrNJ

— Joe Pike (@joepike) December 9, 2019

Footage of the incident was shared widely online but it was swiftly overtaken by two separate information campaigns, both of which appeared to benefit the Conservatives. These attempts to mitigate the damage of Johnson’s behaviour smacked of a co-ordinated influence and disinformation campaign.

Official sources

First, some of the UK’s most visible and high-profile journalists tweeted that a Labour activist at the Leeds hospital where Jack was admitted had punched an advisor to Health Secretary Matt Hancock in the face. Reporting heavyweights Robert Peston and Laura Kuenssberg, political editors at ITV News and BBC News respectively, were among them. Peston reported that the advisor had been ‘whacked’ and Kuenssberg that he had been ‘punched’.

A video soon emerged which showed the advisor had walked into the activist’s hand as he was gesticulating, both looking in opposite directions. Peston and Kuennsberg later deleted the tweets acknowledging their mistakes, both reporting they had been told by “senior Tories” that a punch was thrown but the damage had already been done.

It is completely clear from video footage that @MattHancock‘s adviser was not whacked by a protestor, as I was told by senior Tories, but that he inadvertently walked into a protestor’s hand. I apologise for getting this wrong.

— Robert Peston (@Peston) December 9, 2019

Have video from Hancock leaving Leeds General just come through so you can see for yourself – doesn’t look like punch thrown, rather, one of Tory team walks into protestor’s arm, pretty grim encounter pic.twitter.com/hD1KwA72gG

— Laura Kuenssberg (@bbclaurak) December 9, 2019

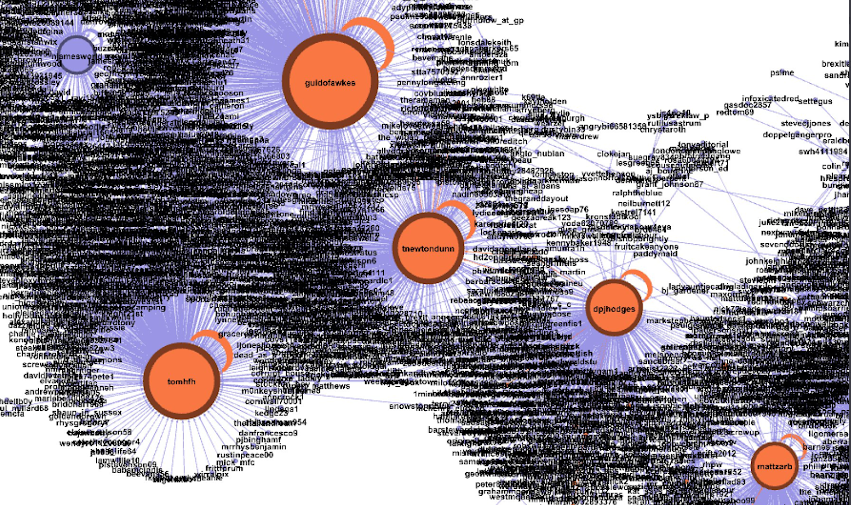

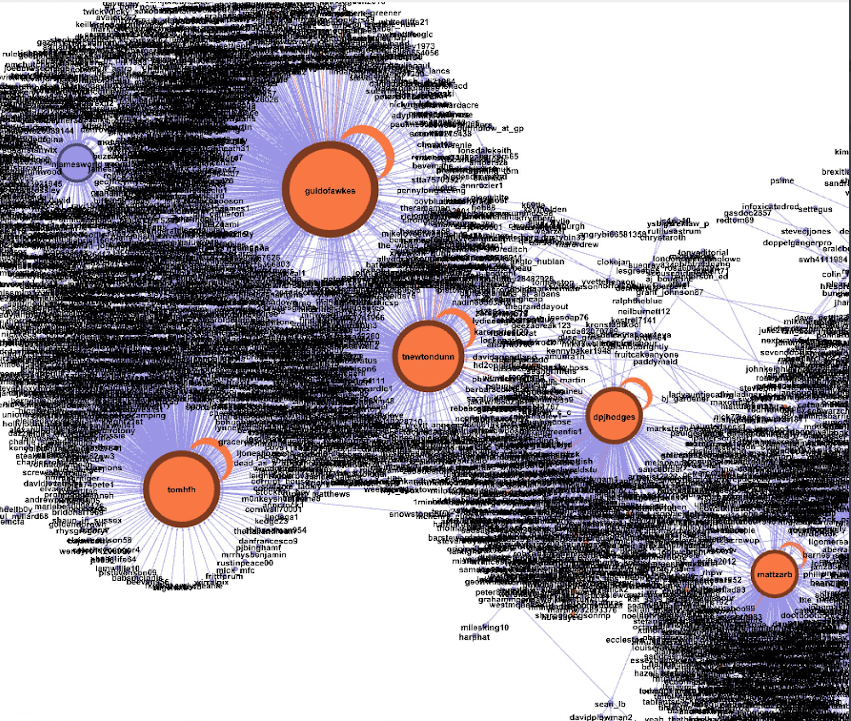

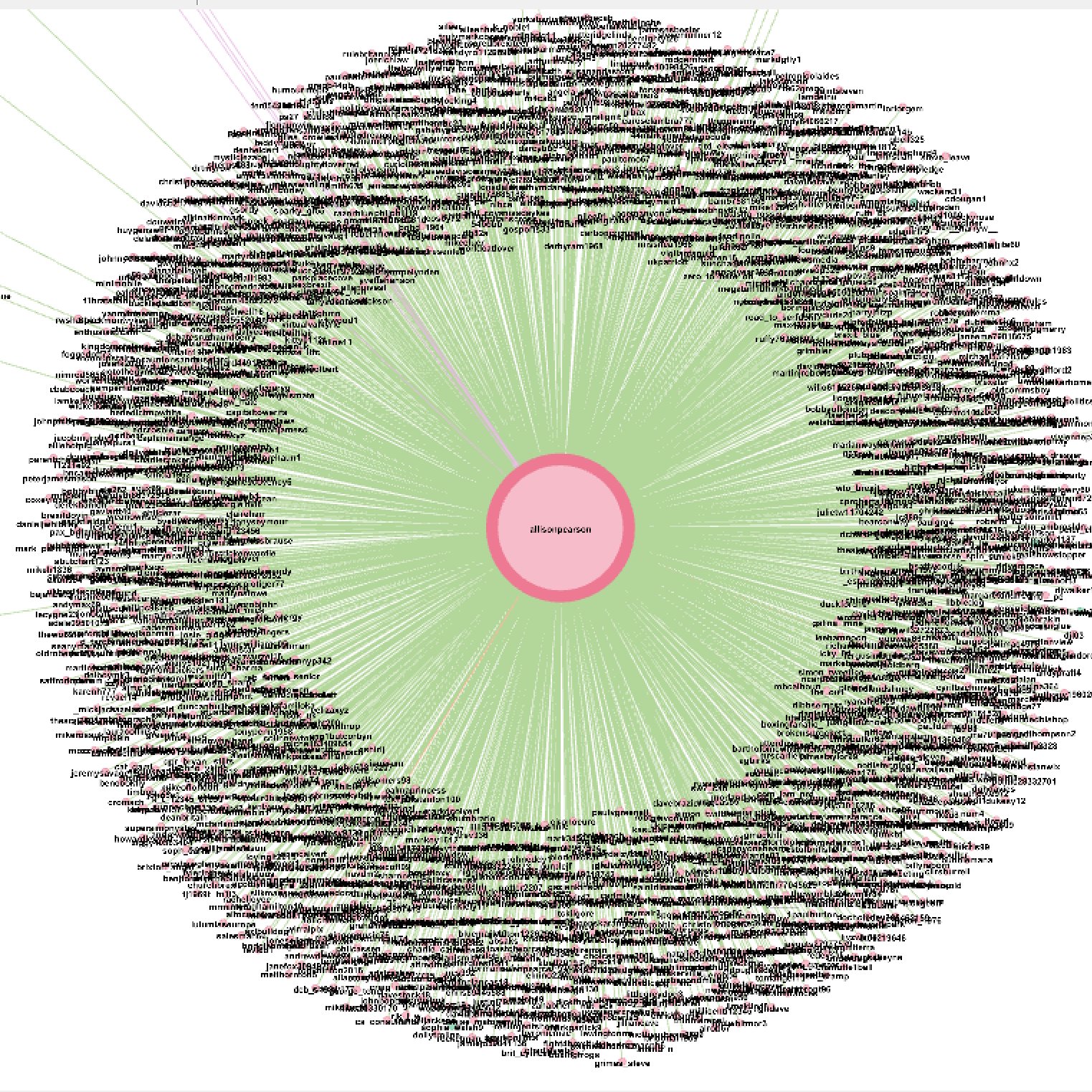

A network analysis highlights the speed at which the disinformation spread, and how long it took before it was effectively countered. A sample of 7,500 Twitter interactions involving around 5,500 unique accounts was taken from Twitter on December 9.

What we can see from the network graph below are the most influential accounts spreading the claim: the rightwing blog Guido Fawkes, its reporter Tom Harwood, and Dan Hodges of the Daily Mail.

A network graph shows the accounts which were central in spreading the ‘punch’ propaganda. Source: Marc Owen Jones.

However, it was Tom Newton Dunn, the political editor of The Sun, that first went public with the ‘punch’ story.

His tweet read: “Today is getting nasty. Matt Hancock’s special adviser has been allegedly punched by a flash mob of Labour supporting activists outside Leeds hospital. The Health Secretary had been dispatched there to deal with the fall out over 4 year-old Jack Willment-Barr.”

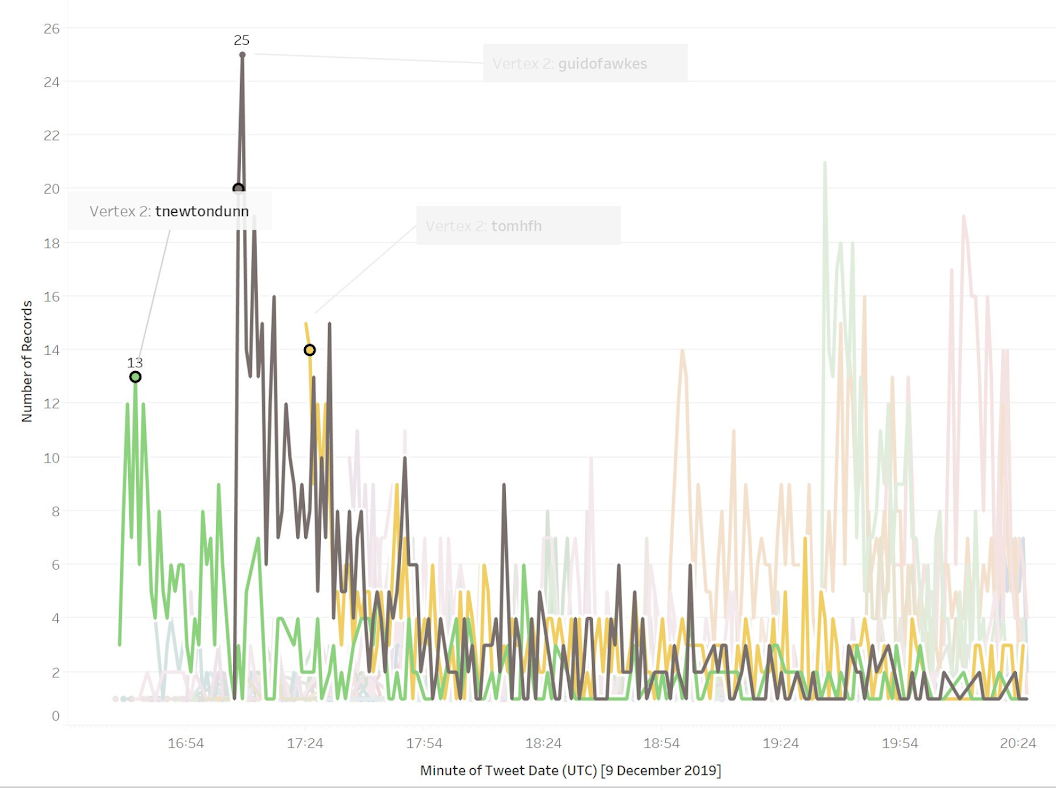

Newton Dunn’s tweet about the punch initially received the most traction. The green line on the time series graph below shows the amount of retweets of Newton Dunn’s tweet received, and how it started soon before the other picked up. Source: Marc Owen Jones.

The brown line represents retweets of Guido Fawkes, and the yellow line that of Tom Harwood. These accounts were tweeting a story about Labour activists being “taxied” in, yet the URL they were sharing still contained the phrase “hancock punched”, from a cached URL leading to the Guido Fawkes blog. Shortly after Newton Dunn’s original tweet, the tweets of Fawkes and Tom Harwood quickly started gaining popularity.

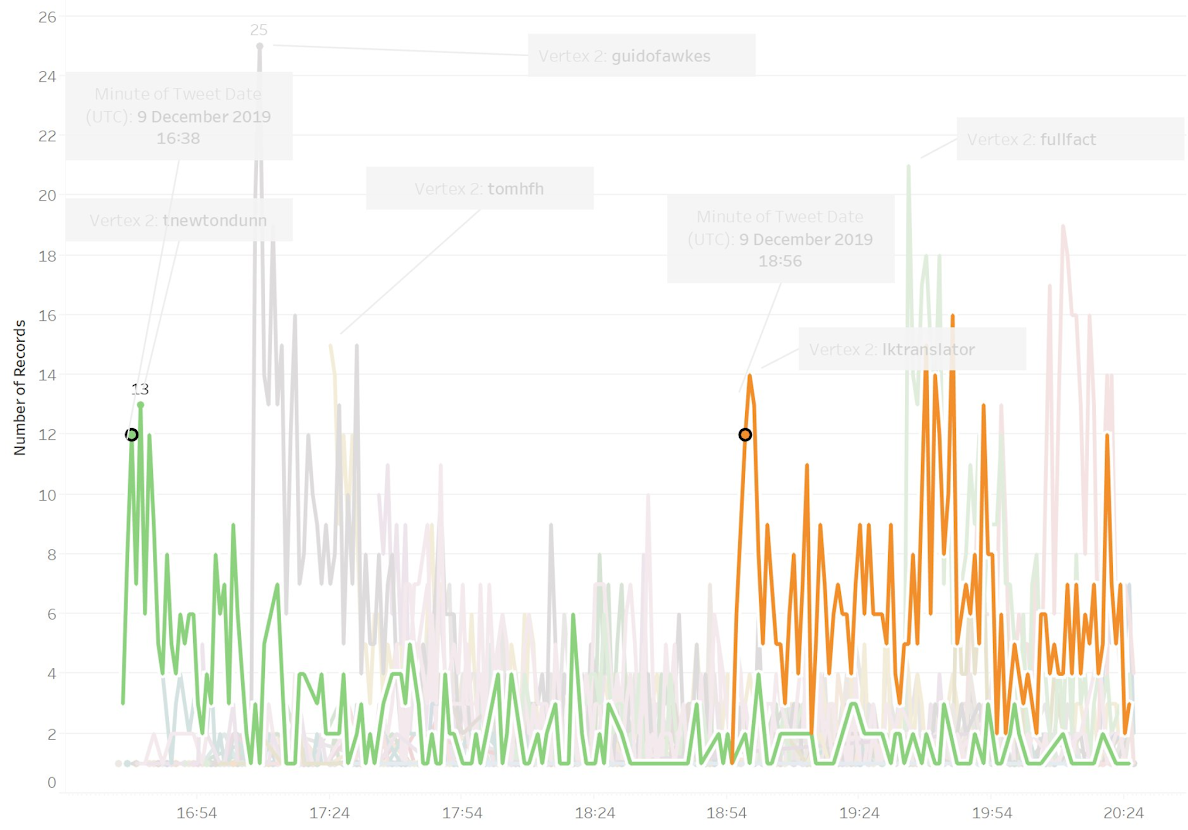

It was only when a popular parody account of the Laura Kuenssberg, called @lktranslator, debunked the original story, that the counter-narrative began to gain popularity. However, this only started gaining traction at 18:56, over two hours after the original tweet by Tom Newton Dunn.

The lag between the dissemination of the disinformation and the counter narrative was substantial, allowing the story to spread and permeate through multiple networks.

It was hours before the truth started to receive widespread attention. Source: Marc Owen Jones.

A Virulent Disinformation Campaign

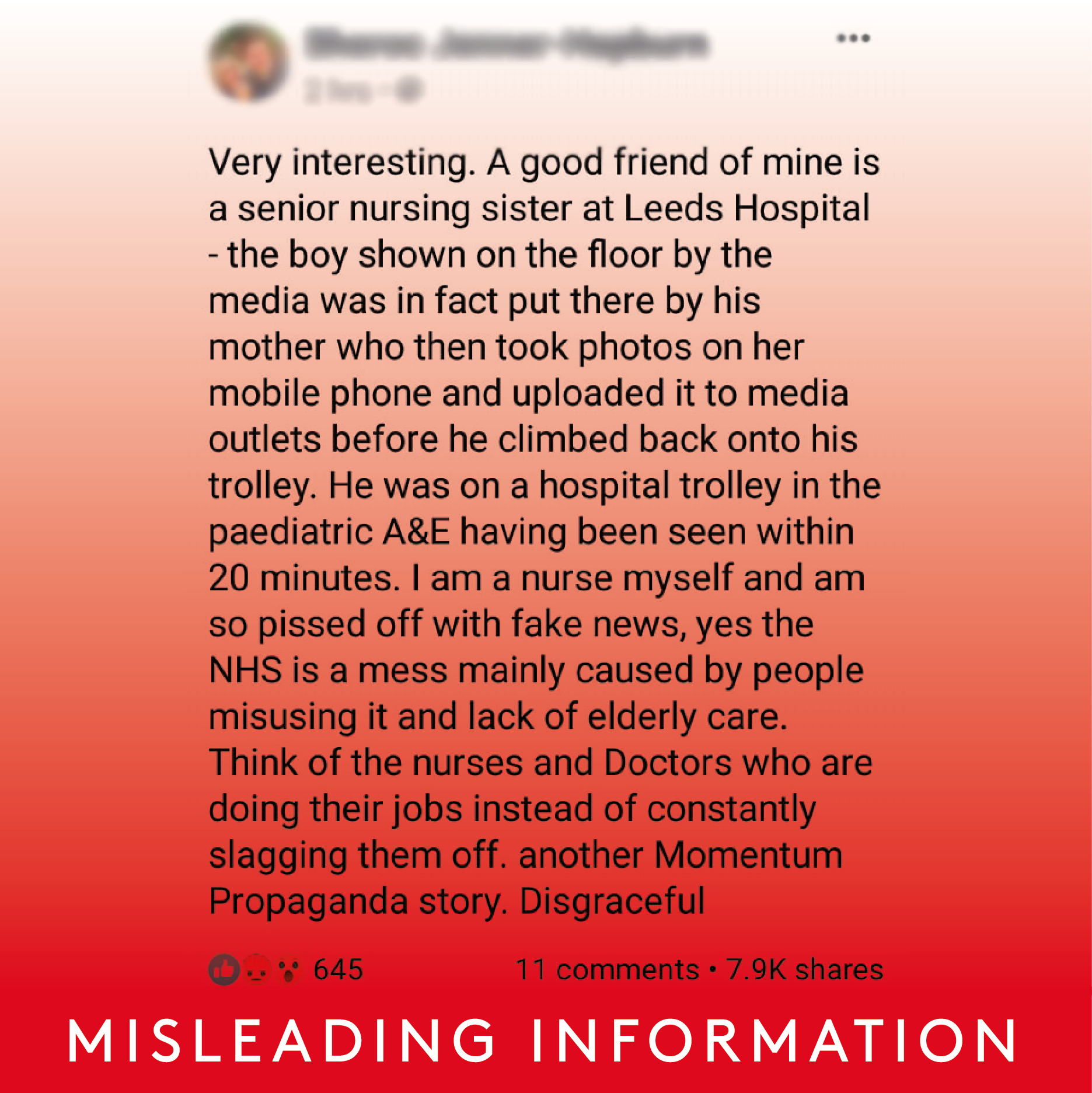

Just as the truth was emerging about the non-existent punch, another coordinated influence campaign was stirring. This time, mysterious accounts on Facebook and Twitter were posting identical text stating that the photo of Jack on the hospital floor had been staged. The message claimed the whole thing was a publicity stunt orchestrated by Labour grassroots movement Momentum.

James Mitchinson, editor of the Yorkshire Evening Post, where the photo of Jack first appeared, issued a long explanation of the lengths he went had gone to ensure the story’s veracity. Crucially, hospital officials had accepted the events as fact and issued an apology. But this came some hours after the claim gained traction online.

I have responded in good faith to Margaret. I do hope we are not too late to help people like her, so unfairly manipluated and discombobulated by cynical social media messaging driven by dark forces. pic.twitter.com/VNhe89dZxz

— James Mitchinson (@JayMitchinson) December 10, 2019

Yet accounts with relatively unknown provenance on Twitter started pasting the text and tweeting it at influencers. Allison Pearson, a columnist for The Telegraph with over 47,000 followers, indulged the story and retweeted a screenshot of the text.

She tweeted the screenshot and received dozens of retweets as a result. The diagram below shows the number of people interacting with Allison over that particular tweet.

This graph shows the accounts which interacted with Telegraph journalists Allison Pearson’s tweet about the hoax claim. Source: Marc Owen Jones.

The screenshot was also tweeted by former England Cricket Team Captain Kevin Pietersen to his 3.4 million followers. Pietersen later deleted the tweet after pressure from other users.

On Facebook, dozens of accounts were posting the same content, verbatim, as either status updates or posts in Facebook groups. Many of the groups were for regional UK communities, such as “Warrington 4 Brexit” or “Seaham of your say” . The posts were then commented on, often by people who believed the narrative. There were also plenty who didn’t.

<

4/ In one example, Jason Crosby pastes the tweet on the FB group for “Seaham Have Your Say”. Seaham have your say is a page with 24k followers serving the North Eastern coastal town of Seaham. His post gets 91 comments and 26 shares. pic.twitter.com/kgW3x31a57

— Marc Owen Jones (@marcowenjones) December 9, 2019

These groups often had tens of thousands of followers. Many of the posts were then commented on, often by people who believed the narrative, and shared hundreds more times.

In a group called “March Cambridgeshire Free Discussion” with 37,000 members, the post attracted 235 comments and 28 shares. The original screenshot taken garnered over 7,000 shares.

Yet the story did not end here. A network of possible sock puppet or hijacked Facebook accounts started posting a second story, in which they claimed to be a former paediatric nurse. They then added their ‘expert’ testimony to debunking the claim.

The same text appeared again on Twitter. However this time they seemed to largely focus their influence efforts on Allison Pearson, who had proved receptive to the initial message. Clearly the co-ordinated influence campaign decided to strike in more inviting waters the second time round. Indeed, if such a disinformation campaign can find a receptive host in a mainstream journalist, the disinformation has a better chance of spreading.

Damning stuff for the tories. I can only assume they really did a number on staffing levels of paediatric A&E and PICU nurses given how many on twitter today apparently left the profession. pic.twitter.com/oJOhnnsZOh

— jingle belle (@pylonfan) December 10, 2019

A third mocked up story was also spread on December 10, again perpetuating the narrative that the Jack story was staged. Like its predecessors, multiple accounts posted the story across Facebook. By this stage, it was unclear whether the accounts posting it were real people who believed the story, or malicious accounts attempting to seed disinformation.

It remains unclear who was behind what was clearly a co-ordinated disinformation operation. A number of outlets reported talking to the woman behind an account where the claim had been screenshotted and shared so widely.

She initially told reporters her Facebook profile had been hacked in order to post the fake story and she had subsequently received death threats. She later admitted she had copied the post from another account and reposted it herself.

The above two cases, on the same day and related to the same event, highlight the dangers of both disinformation and misinformation. In the case of the fake punch, a combination of poor fact checking combined with a volatile partisan atmosphere on Twitter to repeat the story.

With the Jack Williment-Barr story, something more sinister is clearly at play. Nonetheless, both had one common trope. Seasoned journalists and reporters perpetuated unverified and erroneous information far too quickly, increasing the reach and legitimacy of disinformation. On Facebook, malicious actors targeted community groups to make sure their claims reached as wide and receptive an audience as possible to share it further.

The spread of disinformation combines the efforts of malicious actors with the actions of influencers, such as a journalists, who may be unwary or simply caught off guard. These incidents, in the closing stages of a crucial general election, lifted the lid on the machinery of propaganda, in all its gruesome complexity.

Marc Owen Jones is an assistant professor in Middle East Studies and Digital Humanities at Hamad bin Khalifa University in Doha, Qatar.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.