This research was supported by a grant from the Rita Allen Foundation.

By Kaylin Dodson (First Draft), Jacquelyn Mason (Media Democracy Fund) and Rory Smith (First Draft)

Executive Summary

Over 75 per cent of US adults have received at least one Covid-19 vaccination [1]. Yet vaccination rates vary widely across regions and demographics. Among those who have received at least one vaccine (percentages are relative to their total population), 68 per cent are Asian, 52 per cent are white, 48 per cent are Hispanic and 43 per cent are Black [2]. In most states where data is available, Black people are receiving a smaller percentage of vaccines relative to their overall population, despite them accounting for a much larger share of Covid-19 deaths [3][4].

Structural inequities, such as a lack of access to vaccines, have played a large role in limiting vaccine uptake among Black people [5]. While ongoing measures are being taken to increase access to vaccines, and vaccination rates gradually increasing among all populations, these efforts have so far failed to significantly increase vaccine uptake in Black communities [6].

A long history of medical racism and exploitation combined with ongoing discrimination in health care — unequal access to health care facilities, insurance and treatment — has left many Black people distrustful of the medical system and official institutions [7]. Widespread mistrust and lack of access to reliable information about Covid-19 vaccines — on social media platforms such as Facebook, it was found that official information reached far fewer Black people than other demographics — have created an environment under which misinformation can thrive [8][9].

Even where access needs are met, vaccine misinformation represents another obstacle to ensuring people get vaccinated [10]. Where “inequality-driven” mistrust is high, online misinformation can flourish [11][12].

Yet relatively little is known about the most prominent narratives related to Black people and vaccines on social media. And little is known about how these narratives emerge, are interpreted, and possibly amplified by influencers on social media. Understanding how vaccines are being framed online as well as their dynamics on social media is important to creating comprehensive strategies aimed at dispelling misleading vaccine information.

And as new potent and highly transmissible variants such as Delta emerge, it’s vital to close this vaccination gap; otherwise, Covid-19 caseloads will fall disproportionately on Black Americans [13].

With that in mind, First Draft’s research team collected and thematically analyzed the top- performing vaccine-related social media posts surrounding Black communities from November 9, 2020 to June 9, 2021. We looked specifically at posts from unverified Facebook Pages and Groups as well as Instagram and Twitter accounts. We also identified and closely monitored Black anti-vaccine influencers on these same platforms during that time period. The combined research is an attempt to assist journalists, researchers and public communications experts wishing to report and act on potentially problematic vaccine discourse as it relates to Black Americans.

The importance of understanding online narratives affecting Black Americans

Conversations concerning Black communities and health policy are incredibly nuanced, but at times journalists parachute into Black communities and conversations with little knowledge of the context. In doing so, journalists often offer reductionist explanations of complex phenomena and risk misrepresenting the issues. This report highlights the nuance and complexity of vaccine-related narratives surrounding Black communities on social media.

For example, there are indeed narratives and vaccine misinformation that start in non-Black spaces and travel into Black communities. But this doesn’t negate the fact that there are also anti-vaccine narratives that have organically grown from within Black communities. Vaccine shedding and its alleged effects on women’s reproductive health is a narrative that started in white anti-vaccine spaces and was amplified to Black online communities by Black anti-vaccine influencers. On the other hand, vaccine classism and the idea that Black people would receive an inferior vaccine is a narrative that our research shows originated in Black online conversations.

Narratives that seem easily generalizable across all populations become much more intricate and multilayered when looked at through the context of Black communities. For example, the idea that the vaccines are experimental, rushed and unsafe is common among anti-vaxxers of all communities. Yet the narrative becomes more complicated and potent when we consider the history of medical experimentation on Black people and how current concerns reflect this history.

Vaccine hesitancy in Black communities isn’t explained away by vaccine inequity. The reality is that there are Black people who are hesitant to take the vaccine and there are Black people who can’t get vaccinated because of a lack of resources in their communities. Both issues exist in the same space, but lower rates of vaccination among Black communities are often reduced to explanations of vaccine hesitancy or vaccine misinformation.

The idea that Black communities only experience vaccine hesitancy because of histories of medical mistrust and malpractice is another example of reducing complex issues to overly simple explanations. Not every Black person is anti-vaccine or vaccine-hesitant for historical reasons. And not every Black person is genuine in their invocation of Tuskegee, Henrietta Lacks or Jim Crow stories. These histories have not only been weaponized by anti-vaccine members of Black communities but also by non-Black anti-vaccine activists as ways to prey on or even coerce Black communities into rejecting the Covid-19 vaccines. For example, both Black and white conservative pundits have used Jim Crow language and references as a way to condemn the use of vaccine passports.

Because this research is based on social media data and conversations online, it may not accurately reflect the many conversations that Black people are having about vaccines offline. As complicated as the online narratives are, the conversations that are playing out in Black communities across the US are even more nuanced. For journalists and policymakers this is an important reminder to not only look at conversations happening online, but also to interact directly with these communities to better understand the issues that might be contributing to lower vaccination rates. As we have stated before, Black people are not monoliths and the same goes for the issues affecting Black communities. And we should never assume that the conversations occurring on social media represent the myriad conversations happening in real life.

Key Findings

Mistrust of Covid-19 vaccines and the motivations of official institutions pervade vaccine-related posts surrounding Black communities. Across the data analyzed, posts mistrustful of Covid-19 vaccines and the official institutions tasked with getting Black people vaccinated were dominant. Televised events aimed at winning Black people’s confidence in the vaccine were often met with mistrust and suspicion by Black voices on social media who saw them as attempts to coerce Black people into getting the vaccine.

Misleading vaccine posts are often multidimensional; anti-vaccine rhetoric feeds into existing anxieties that stem from systemic racism. Misleading vaccine claims aimed at Black audiences on social media are often based on past medical harms and examples of current institutional racism, such as the ongoing Black maternal health crisis. Where mistrust in institutions is already high, these posts, which are both emotive and appended with anti-vaccine claims, can be even more potent.

Many Black anti-vaccine influencers are still able to spread misleading vaccine content with relative impunity on social media. We identified many examples of misleading information and falsehoods among the posts we analyzed for this report. While some of these posts contained a kernel of truth, which may have complicated moderation efforts, many posts were clear examples of vaccine misinformation. These posts remain active on social media, specifically on Facebook and Instagram, where the majority of conspiracy theory-related posts appear. Many anti-vaccine posts on Instagram have only received a Covid-19 vaccine disclaimer over the content. The feature is indiscriminately applied to posts mentioning Covid-19 or vaccines, regardless of whether they contain misinformation. Multiple Black anti-vaccine influencers, including Chakabars Clarke, Imani Cohen, Brother King Cam and Dr. Wesley Muhammad, have had their anti-vaccine content stay up on Instagram with no repercussions or removal unless the account managers themselves deleted the content.

Anti-vaccine content proliferating in predominantly white wellness communities has seeped into Black spaces on social media. Popular false narratives coming from white wellness influencers and anti-vaccine spaces on social media, such as that vaccines are dangerous for women, cause infertility and result in “shedding,” have moved into Black spaces on social media. The mistrust by some Black people of healthcare institutions — the culmination of years of institutional racism, exploitation and medical experimentation — has fostered the spread and stickiness of these narratives.

Right-wing personalities and media outlets have co-opted Black vaccination concerns to further politicize Covid-19 vaccines. Campaigns to get Black people vaccinated, which caused suspicion in some online Black communities, have been appropriated by right-wing media outlets and social media users to erode trust in the Biden administration and stoke concerns about the legitimacy of Covid-19 vaccines. For example, legitimate concerns about how “vaccine passports” might unfairly affect Black people have been used to position the idea as a new flashpoint in the pandemic culture war.

Online narratives affecting Black communities are nuanced and multilayered. A failure to recognize this will result in reporting that misrepresents the depth of issues affecting Black communities. Our research and monitoring have shown that vaccine-related narratives surrounding Black communities are not monolithic, but evolving. Narratives that are seemingly opposed can exist in the same online spaces and have the same amount of explanatory impact. For example, it is a common belief that conversations about vaccine hesitancy in Black communities can be explained away by focusing on vaccine inequity facing Black communities. However, understanding both vaccine inequity and vaccine hesitancy is equally important when explaining low vaccination rates in Black communities. Importantly, high-engagement vaccine-related conversations online don’t necessarily represent conversations happening on the ground in Black communities.

Machine learning classifiers trained on general vaccine-related social media content will miss important signals specific to Black communities and will likely misrepresent them. Different communities face specific issues whose historical and modern underpinnings are different from the general population. Applying machine learning models trained on general vaccine content to classify vaccine-related conversations in Black spaces on social media has the potential to miss important nuances and signals, hindering efforts to make sense of these conversations online. Models trained specifically on vaccine-related data from Black spaces online will be needed to avoid this. Even then, new issues will likely emerge, requiring the addition of topics and models.

Based on this report, we offer a series of recommendations for platforms, policymakers, communications professionals, journalists and researchers, all of whom play essential roles in ensuring that access to reliable information related to vaccines is equitable and reaches Black communities.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: Social media companies must more consistently act on policy violations by influencers with large followings, including Black influencers. Social media platforms must more consistently enforce their policies against Covid-19 and vaccine misinformation when anti-vaccine influencers with large followings violate those rules. Taking down smaller accounts that disseminate harmful misinformation to Black communities is inadequate when more prominent accounts — such as those of Summer Walker and Chakabars Clarke — share anti-vaccine information to millions of followers with seemingly minimal consequences. Adding content disclaimers to viral anti-vaccine posts — disclaimers that also appear on much generic vaccine-related content — is not likely to blunt the impact of these accounts’ huge and dedicated followings. Without consistent moderation for large accounts, vaccine misinformation will continue to infiltrate Black communities.

Recommendation 2: Facebook and Instagram must allow better data access to researchers and journalists investigating the kinds of information presented to Black communities on these platforms. Black communities in the US have suffered a long history of medical and institutional racism that has resulted in deep structural inequalities that continue to play out. Poor access to good information represents another structural inequity. Without access to more data, journalists and researchers will face difficulties investigating the full extent to which Black communities are exposed to dangerous health misinformation, and they will not see how moderation policies might differ among different demographics. Without better access to data, there is no way to ensure that mainstream platforms such as Facebook and Instagram are guaranteeing equitable access to reliable information.

Recommendation 3: Journalists and researchers investigating misinformation targeting Black people must pay greater attention to alternative social media platforms popular among Black communities. Black online spaces are expansive; vaccine content moves quickly across both mainstream and alternative platforms. Vaccine-related content that starts on audio-only apps such as Clubhouse can easily migrate either to fringe websites such as Lipstick Alley or to more mainstream platforms such as Twitter. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter remain important spaces to monitor for misinformation and to identify narratives relevant to Black communities. However, in order to identify misinformation narratives that affect Black people before they reach a wider audience, it’s important to monitor popular alternative platforms.

Recommendation 4: Journalists need to acknowledge the origins of Black mistrust around Covid-19 vaccines and be less reductionist in their reporting. A failure to do so can result in misleading and harmful narratives. A history of medical and institutional racism, much of which continues today, has resulted in widespread mistrust of official institutions in the US among Black people. While mistrust in official institutions can make populations more susceptible to misinformation, mistrust in itself does not directly equate to the production of or belief in vaccine misinformation or anti-vaccine narratives. Many Black people intend to get vaccinated but have adopted a “wait and see” stance. There are myriad reasons for lower rates of vaccination among Black populations. By using misinformation as a scapegoat instead of addressing widespread, inequality-driven mistrust and other obstacles, such as structural barriers to access, journalists and media outlets risk misleading the public and policymakers about the reasons for lower Covid-19 uptake in Black communities, complicating efforts to build trust in vaccines.

Recommendation 5: Greater emphasis should be put on considering vaccine narratives (both positive and negative) as a whole instead of separate entities. Journalists and researchers should consider vaccine narratives as a web of information that only makes sense within a larger context. Focusing on only one narrative, or only on misinformation, risks missing important signals that when considered together can help explain more profound phenomena (in this case mistrust in official institutions among Black communities). Furthermore, an overemphasis on one narrative risks sidelining other important and inchoate narratives that could potentially result in data deficits and misinformation [14].

Background

Black and Hispanic communities have been hit especially hard by the Covid-19 pandemic. Long-term structural and economic racism has meant that Black people are overrepresented among those working essential jobs [15]. These same factors have also resulted in Black people experiencing health conditions associated with a higher likelihood of dying from Covid-19, such as diabetes, hypertension, asthma and obesity, at much higher rates than white people [16]. Redlining policies and housing segregation mean that many Black people live in overcrowded housing, putting them at higher risk of being exposed to Covid-19 [17].

As Covid-19 continues to spread and more dangerous variants emerge, closing the vaccination gap will be critical to avoid spiking Covid-19 cases and deaths within Black communities as well as the economic setbacks that such an outcome would bring [18].

Yet there are obstacles to increasing vaccine uptake in Black communities. Structural barriers to access, such as work and family responsibilities and hard-to-reach vaccine sites for people without cars or who have poor access to public transportation, complicate efforts to get Black people vaccinated [19].

Black people have endured a long history of medical exploitation and racism. While the Tuskegee experiment is one example often mentioned on social media, it wasn’t the only such incident of medical racism, nor was it the first [20]. Dr. James Marion Sims conducted brutal experiments from 1845-1849 on enslaved African women without anesthesia to create a surgery that would repair vesico-vaginal fistulae [21]. And cancerous cervical cells were taken from Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman, without her consent; these cells have been widely used to advance science [22]. While these are only a few examples of the kinds of historical abuse to which Black people were subjected, the trauma of these events remains fresh in the minds of many and has eroded trust in the medical system.

Little has been done to mitigate this mistrust. Mistreatment and racism remain rife in today’s medical system. The Black maternal crisis — Black women are three times more likely to die as a result of pregnancy than white women — is only one example of how healthcare inequalities negatively affect Black communities [23]. The history of police killings of Black people, which captured the world’s attention in the wake of George Floyd’s murder last summer, has only emphasized the structural inequalities and racism facing Black communities in the US.

Pervasive mistrust resulting from these factors has made many Black people wary of Covid-19 vaccines, contributing in part to many people adopting a “wait and see” approach [24]. Rampant vaccine misinformation across social media, including in Black spaces, is compounding these issues. While misinformation can fuel mistrust, the relationship isn’t one-way; mistrust also makes people more receptive to misinformation [25].

Any effort to build trust and encourage vaccines among Black populations would benefit from understanding the key narratives and vaccine-related misinformation circulating online. While not on its own an adequate solution, used in conjunction with community outreach efforts the identification of key online narratives and misinformation can help to dispel misinformation, build trust and close the vaccination gap.

Methodology and Limitations

Identifying vaccine-related posts on social media is a fairly straightforward task, which in essence requires a detailed set of vaccine-related search terms. However, identifying vaccine-related posts as they pertain to a particular demographic is more challenging, given the lack of publicly available metadata that might provide this kind of robust information. Without access to this data, it’s nearly impossible to determine who is behind each social media account, which complicates efforts to isolate accounts or Pages operated by an individual who identifies as Black. While determining the identity of Instagram and Twitter accounts may be feasible in some instances, especially if you are monitoring an account’s day-to-day activity over a long period of time, ascertaining whether that person is 1) actually operating the account and 2) the only individual operating that account will always remain a challenge.

As a result, we were unable to identify posts emanating from only accounts operated by individuals identifying as Black people. The closeness that researchers glean from manual and daily analysis of social media allows for more confidence in determining whether the accounts engaging in vaccine conversations are primarily Black and their messages aimed at Black people. Nonetheless, because we examined public data and posts — posts that anyone, including any demographic, could access — and because we suffer from the same data limitations listed above, it’s difficult to say whether this content was aimed at and consumed exclusively by Black people.

To get as close as possible to posts relating to and affecting Black people on social media, we used a two-pronged qualitative mixed-methods approach (detailed below) which combined specific keywords and Boolean operators to gather posts that we believed were either created by, aimed at and/or consumed by Black people. In addition, we undertook manual daily monitoring of specific Black influencers on social media. At best, the data we analyzed and the social media activity we monitored approximate posts coming from, relating to and surrounding Black communities in the US. However, they are not all from individuals identifying as Black.

It’s important to remember that the term “Black communities” doesn’t represent a monolithic and homogenous population. Like all populations, there are many different Black populations and communities with disparate concerns and experiences. However, because of the aforementioned data constraints, we were unable to rigorously disaggregate between these populations.

The aim of this research report was to both identify the top vaccine-related narratives on social media surrounding Black communities as well as better understand the dynamics of this particular information ecosystem — this includes, among other things, identifying influential figures pushing misleading vaccine information as well as how platforms respond to this content. As such, we opted for a qualitative-centric mixed-methods approach that combined 1) static analysis of the most engaged-with vaccine-related posts surrounding Black communities from November 9, 2020, to June 9, 2021, with 2) dynamic analysis of posts through our day-to-day monitoring of Black spaces on social media during that same time period.

Taking slices of data, such as the most engaged-with posts, is useful for determining the top themes and narratives during a particular time frame as it allows us to support what we find qualitatively with quantitative data (engagement metrics). However, because this approach is static — it isolates data during a particular time period — it misses much of the nuance and dynamics at play within a specific information ecosystem — in this case vaccine discussions on social media pertaining to Black communities in the US. Moreover, certain data constraints, such as the limited Instagram data accessible through the Facebook-owned social listening platform CrowdTangle as well as the removal and disappearance of tweets including all available data, means that we may have missed important posts in our data collection.

To counterbalance this imperfect methodology, we focused a portion of First Draft’s collective daily monitoring efforts on vaccine-related conversations pertaining to Black communities on social media. By tracking vaccine-related discussions in real-time (a dynamic approach), we were able to identify, among other things, the core accounts influencing vaccine-related conversations in Black spaces on social media, the different ways in which these narratives were interpreted, how they were spread and the consistency or lack thereof with which social media platforms moderated content in violation of their own policies.

The key findings in this report are based on this mixed-methods approach, where both the static and dynamic approaches fed off and supported each other. Because our research is based on online conversations, some things that are prominent online and in this data might not be as prominent or even have the same framing in conversations that are occurring on the ground within these communities. When designing policy or communications strategies, our findings should be paired with focus groups, surveys or other forms of qualitative research involving members from Black communities.

Below we offer more details on the methods used for both the static and dynamic approaches to our research.

Static data analysis:

We collected the top 100 most interacted-with posts from four separate entities: unverified Facebook Pages, Facebook Groups, Instagram accounts and Twitter accounts, between November 9, 2020, and June 9, 2021. The final dataset consisted of 400 total posts, 100 posts per entity. We chose to work with unverified accounts as we wanted to best capture the individual voices and conversations occurring under the surface. The most interacted-with posts from verified accounts are often from large media organizations and don’t necessarily reflect the voices and conversations happening on social media around vaccines. Posts from Facebook and Instagram were collected by querying CrowdTangle’s API for posts containing different combinations of keywords relating to vaccines and Black people. For Twitter data, we used Twitter’s Streaming API with the same combination of keywords. To avoid false positives, we conducted a secondary layer of filtering, using more specific keyword combinations to isolate vaccine-related posts surrounding Black communities. We then borrowed Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke’s methodology for thematic analysis to code and identify key narratives and topics that emerged from the dataset [26]. This consisted of:

- Familiarizing ourselves with the data

- Manually coding the data

- Generating initial narratives

- Reviewing the narratives

- Defining and naming the narratives

- Writing up the results

Dynamic data analysis:

We identified Black influencers who frequently produced anti-vaccine content and monitored and mapped anti-vaccine narratives emanating from these accounts. Influencers were found by conducting targeted Boolean searches on Tweetdeck and CrowdTangle. They were also sourced by following a news or popular culture topic around vaccines and identifying those accounts with significant followings that were perpetuating common misleading claims, such as the false narrative that Covid-19 vaccines are experimental, rushed and unsafe.

We identified other influencers in Rooms that had received significant attention on the audio-only discussion app Clubhouse. We traced users we found on Clubhouse spreading vaccine misinformation to their accounts on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter. Influencers were selected based on the frequency with which they produced anti-vaccine content, the number of followers they had, and the engagement that these accounts received for their posts.

Two researchers who consumed and monitored content in Black spaces each day employed different ethnographic techniques to analyze posts from the influencers and lists of accounts identified as being relevant to the vaccine discourse surrounding Black communities. The researchers cross-referenced their results with findings from the static analysis.

Topics, Narratives and Misinformation

To understand vaccine discourse on social media, it isn’t enough to monitor and verify individual pieces of content. We have to understand that individual pieces of content create larger attitude- shaping narratives. And these narratives fall into even larger, overarching topics that steer conversations and allow us to make sense of the superabundance of vaccine-related information on social media.

In a previous piece of First Draft research — Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation and data deficits on social media — we identified dominant vaccine narratives and topics on social media platforms in English-, French- and Spanish-speaking communities that could erode public trust in Covid-19 vaccines, and vaccines more generally [27].

The resulting taxonomy we created is useful in categorizing general vaccine-related posts and is currently being leveraged to build machine learning models to automatically classify vaccine content on social media. Yet it’s unclear how valuable that taxonomy is when making sense of demographic-specific vaccine-related conversations on social media. Different communities face specific issues whose historical and modern underpinnings are different from the general population. Implementing the current taxonomy for vaccine conversations in Black spaces on social media, for example, has the potential to miss important nuances and signals, hampering efforts to make sense of these conversations online.

To better understand the narratives we surfaced and their position not only in vaccine discourse but in the greater political discourse in the US, we made an initial attempt to classify these narratives under broader themes. It’s important to note that these themes are far from exhaustive. More research involving significantly more data will be needed to approximate anything akin to an exhaustive taxonomy. And even then, new issues will likely emerge, requiring the addition of topics.

It’s also important to note that while the narratives that emerged from our data can be categorized and framed under Class, Equity and Safety, the narratives that fall under these topics are not mutually exclusive. Black communities are not a demographic monolith; a narrative can signify very different things to different constituents of Black communities. For example, while we placed the narratives surrounding Dr. Kizzmekia Corbett under Class — these narratives emphasized Class concerns — some of the skepticism that emerged around these narratives was also rooted in concerns about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines.

Below we present the narratives and their topics, with an explainer for each topic.

Class

This section includes narratives that speak to the intersections of race and class that have been highlighted during the vaccines’ rollout and vaccination efforts. Because of histories of Black communities not having access to quality medical support, something that has been a concern is the risk of Black people with lower incomes not getting the same quality of vaccine that their richer white counterparts have received. Critically, there is also an element of mistrust aimed at the “Black elite” [28], or upper-class Black Americans who have high influence, who seemingly “teamed up” with white liberals almost to coerce Black communities into getting vaccinated. An example of this can be seen with the vaccination efforts of Tyler Perry, Hank Aaron and the Rev. Jesse Jackson being tied to various conspiracy theories and false narratives.

Below are the most prominent narratives that have emerged from our research on the topic of class.

Narratives about a Black female scientist’s key role in development of a Covid-19 vaccine

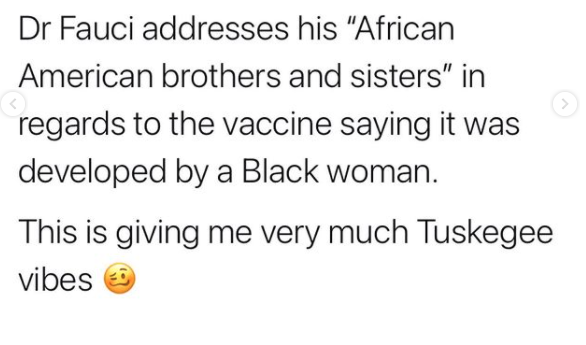

The most dominant narrative that appeared in our dataset concerned Dr. Kizzmekia (Kizzy) Corbett — the scientific lead of the Vaccine Research Center’s (VRC) Coronavirus Team — and the role she played in the development of Moderna’s Covid-19 vaccine. In December, shortly after Pfizer and Moderna had each announced the efficacy of their respective vaccines in preventing Covid-19, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, appeared in a forum hosted by the National Urban League and underlined Corbett’s critical role in creating a Covid-19 vaccine [29]. Shortly thereafter, social media was awash with posts and news stories with headlines such as, “Fauci wants people to know that one of [the] lead scientists who developed the Covid-19 vaccine is a Black woman” [30]. In many of the news stories, Fauci is quoted as saying: “So, the first thing you might want to say to my African American brothers and sisters is that the vaccine that you’re going to be taking was developed by an African American woman. And that is just a fact.” [31]

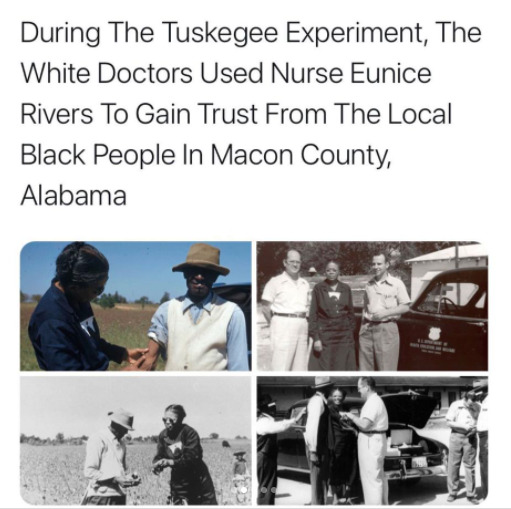

Yet other social posts were more skeptical of Fauci’s announcement, comparing Corbett to Eunice Rivers — the nurse who recruited 600 African American men to participate in the Tuskegee syphilis experiment.

Screenshot by the authors

It’s important to remember that while many posts reference the Tuskegee experiments, it’s not because the incident is the only example of medical racism. Rather, Tuskegee has come to represent numerous acts of abuse by the government and medical establishment — and the risk of this abuse being repeated.

Separately, right-wing outlets used Fauci’s comments and his praise for Corbett to attack and undermine people’s trust in him.

Screenshot by authors

That the narrative could take on multiple meanings is unsurprising. Fauci is derided by many on the right, while the legacy of racist and unequal medical treatment in the US — which continues to this day — has made many Black people distrust the medical establishment [32]. Black Americans’ trust in the media — similar to other demographics — is low [33]; communication strategies involving outsiders who fail to connect directly with Black communities are likely to be ineffective, according to experts [34] [35].

Most social media posts, however, framed the announcement in a positive and empowering light, portraying Corbett as a herald of positive change within the overwhelmingly white medical establishment [36] [37].

Narrative suggesting that white liberals and the “Black liberal elite” are trying to coerce Black communities into being vaccinated

Similar to the aforementioned narrative, the idea that white liberals and the “Black liberal elite” are trying to coerce Black communities to get the vaccine through heavy advertising was also prominent. Various accounts, some connected to Black conservatives such as Olivia Rondeau, framed announcements like Fauci’s as well as news coverage showing Black medical professionals and celebrities getting vaccinated as a vast marketing campaign to court Black participation in an “unsafe” vaccine.

Other Black conservative accounts, such as Charrise Lane, asserted that the long history of medical racism — for example, using Black people as “guinea pigs” in the Tuskegee experiments — makes Black people mistrustful of the government, especially as it only reaches out to Black people when it needs something from them.

Other accounts pointed to the heightened media attention on getting Black people vaccinated as opposed to other demographics, such as white Republican men, as a double standard and a harbinger of something more nefarious.

Screenshot by authors

Posts supporting this narrative underlined a deep sense of mistrust in the medical establishment. Yet the politicization of this narrative — pitting liberal whites and liberal Black people against others in Black communities — threatens to further divide those communities that have suffered disproportionately from Covid-19 as well as to sow more mistrust, not only of the medical establishment but also the Biden administration. The politicization of the Covid-19 vaccine among white male Republicans has contributed to making them one of the most vaccine-resistant populations in the US [38]. This same politicization could also increase skepticism about Covid-19 vaccines among conservative Black communities.

Narratives arguing Black people are getting an inferior vaccine

Ahead of and during the rollout of the Johnson & Johnson Covid-19 vaccine, there was outcry and skepticism on social media about the perception that a vaccine with a lower efficacy rate would be offered in poorer communities of color. Despite news outlets such as The Washington Post explaining that it is thought to be more practical to send the Johnson & Johnson vaccine to harder-to-reach communities because it is a single-shot vaccine and is easier to store than the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines [39], the distinction was perceived by many in Black communities as representing a “two-tiered vaccine system” where the vaccines’ distribution was divided among class and race lines [40].

Equity

The topic of equity includes narratives pertaining to accessibility and fairness in vaccination efforts targeted to Black communities. This section highlights some of the reasons vaccination rates in Black communities have been low or plateauing despite rigorous campaigning. It is also important to note that some real issues of vaccine accessibility and equity in Black communities have been co-opted and used as bad-faith comparisons to push anti-vaccine rhetoric.

Below are the most popular narratives that have emerged from our research under the topic of equity.

Narratives contrasting issues of access with hesitancy

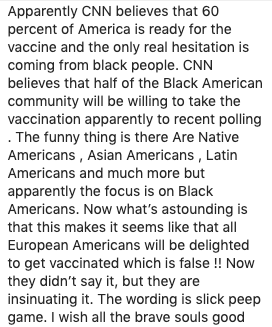

The idea that too much emphasis is being put on vaccine hesitancy among Black communities and not enough attention is being paid to structural racism, such as the lack of access to vaccines and vaccine clinics, was a core narrative in our data. Early in the vaccine rollout, it was common to see news headlines suggesting that hesitancy [41] — fueled in part by misinformation [42] — was the main factor hampering vaccination efforts.

While the reasons for vaccine hesitancy are complex, varying by context, time and vaccine [43], mistrust in institutions is a common element of hesitancy, along with the history of medical racism and perceptions of vaccines as unsafe [44]. However, the disproportionate amount of news coverage that focused on Black hesitancy — much of it centered on the Tuskegee experiments — obscured important issues related to access.

Despite the willingness to get vaccinated by many in the community, structural constraints, such as lack of transportation, inconvenient vaccine clinic operating hours and locations as well as the costs of missing work to get a vaccine, have frustrated efforts for many Black people to get vaccinated [45]. Access to reliable vaccine information for Black communities has also been a major roadblock. An investigation by The Markup showed that on social media platforms such as Facebook, official information about Covid-19 vaccines reached fewer Black people than other demographics [46].

Numerous posts highlighted this overemphasis on hesitancy, underlining how it was another example of “racecraft,” where focusing exclusively on “hesitancy implicitly blames Black communities for their undervaccination” while at the same time concealing opportunities to address roadblocks to vaccine uptake [47][48].

Screenshot by authors

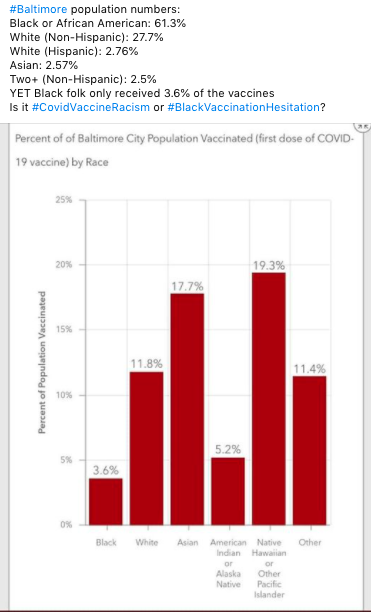

Other posts from Facebook Groups and Pages related to particular cities pointed out the stark inequalities in vaccine access — significantly more white people were initially able to access the vaccines despite Black people making up a majority of the population.

Screenshot by authors

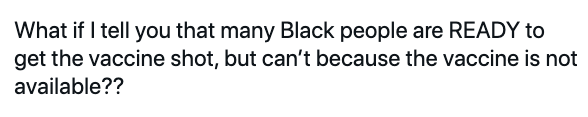

Various accounts stressed that Black people, in contrast to much reporting, were willing and ready to get vaccines but that access issues were limiting these efforts. This sentiment was echoed by polls at the time that showed most Black people intended to get the vaccine [49].

Screenshot by authors

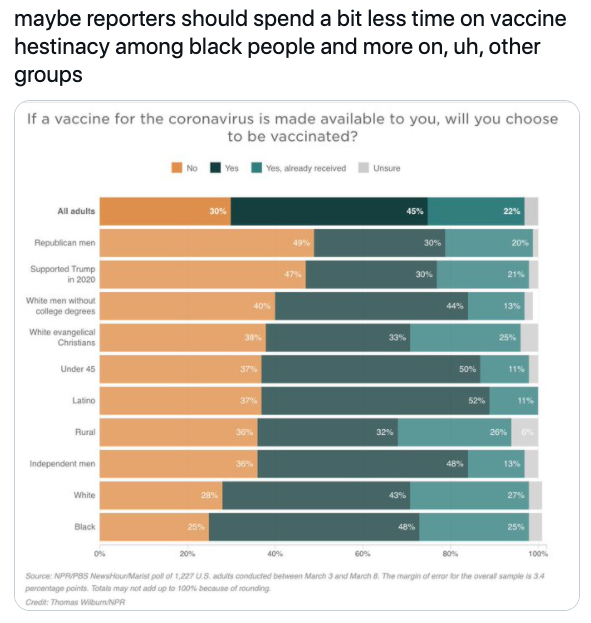

The media and journalists were also criticized in numerous posts for their tendency to focus so heavily on Black people at the expense of reporting on hesitancy in white, especially conservative, populations.

Screenshot by authors

And still more posts supporting this narrative shared a KQED article arguing that focusing on hesitancy and the role of Tuskegee in fostering Black hesitancy about a Covid-19 vaccine was a “scapegoat,” absolving people from digging in and learning about the many reasons, including structural racism and access issues, that have prevented Black people from getting vaccinated [50].

Narratives suggesting vaccine passports are discriminatory and an infringement on rights

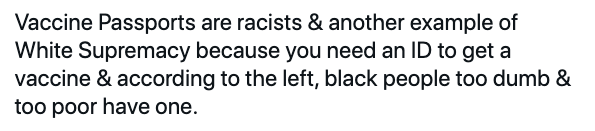

Objection to “vaccine passports,” or vaccine certificates, calling them unethical or an infringement on rights, is being promoted by conservative-leaning influencers whose posts we examined [51][52][53]. These are bad faith comparisons made by both Black and white influencers. These comparisons actively ignore the historical complexities as a way to justify anti-vaccine rhetoric. Other posts claim that vaccine passports are discriminatory.

Concern about the potentially discriminatory nature of vaccine certificates is real — it’s feared that minority communities and the poor would suffer disproportionately because they have been hindered from getting vaccines [54]. However, right-wing media outlets and influencers have begun to capitalize on these concerns about discrimination in an effort to position vaccine passports as a new flashpoint in the pandemic “culture war.” [55][56]

In an attempt to malign the left, other conservative Black influencers such as Melissa Tate have alleged that vaccine passports are racist and an example of white supremacy.

Screenshot by authors

This debate is likely to intensify as the Biden Administration mandates Covid-19 vaccines for up to 100 million Americans [57].

Safety

The topic of safety includes all narratives pertaining not only to concerns about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines but also to vaccine initiatives (government-led or otherwise) that are perceived as having more nefarious intent that could jeopardize the safety and health of those in Black communities. It’s important to remember that having concerns about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines doesn’t mean a person is an anti-vaccination activist. Being vaccine hesitant is very different from being “anti-vaxx” and conflating vaccine-hesitant individuals with “anti-vaxxers” can result in stigmatization [58]. Furthermore, safety concerns around Covid-19 vaccines in Black communities are real and often rooted in the long history of medical racism, experimentation and systemic exploitation experienced by these communities, much of which continues today [59].

Below we take a look at the most salient narratives that emerged from our data under the topic of safety.

Narrative that the Covid-19 vaccine is experimental, rushed and unsafe

This popular narrative, whose popularity predated the Covid-19 vaccines’ rollout [60], featured heavily among posts in our general dataset and among the Black influencer accounts we closely monitored. Various posts from the accounts of Tariq Nasheed (activist and founder of Foundational Black Americans) and the Facebook page of Samantha Morlote (an ambassador for the conservative group Lexit) pointed to the deaths of prominent African Americans shortly after receiving the Covid-19 vaccine, including Hank Aaron, Karen Hudson-Samuels and television contributor Midwin Charles, as evidence of the vaccines being unsafe. In one tweet referencing Charles’s death, Nasheed posted “… everyone seems suspiciously quiet on the potential cause of death. I wonder why?”

While the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that it “has not established a causal link” between reports of death and the Covid-19 vaccine, many posts expressed skepticism concerning the vaccines’ safety [61].

Various videos of a Black female nurse claiming to have developed Bell’s palsy were also used to support this narrative, despite there being no record of a registered nurse developing the condition [62].

Posts from various members of the Nation of Islam, such as the Facebook Page of Dr. Wesley Muhammad, also supported this narrative, putting forth more conspiracy theory-related messages. One post from Muhammad’s Page read, “As I said in ‘Beyond Tuskegee Part I,’ this fight against the Vaccine Mafia who are targeting Black People with their experimental military technology disguised as a vaccine, is THE fight of this generation.”

Screenshot by authors

Misleading narratives about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines have been circulating on social media since the beginning of the pandemic [63]. Since the rollout of Covid-19 vaccines in December 2020, misleading claims asserting the development of the vaccines was “rushed” and that they are “experimental” have spread widely across social media. These unsubstantiated claims are often used to support the false idea that Covid-19 vaccines are unsafe. Many people who still have not received the vaccine, regardless of race, have opted for a “wait and see” strategy, with many citing concerns about vaccine safety [64].

All of the posts we identified claiming Covid-19 vaccines are unsafe and experimental remain active on social media, despite their misleading nature.

Narrative contrasting the idea of Black people’s mistrust of vaccines with emphasis on history of medical racism against Black people

Another dominant narrative concerned the need for the media, medical establishment and government to first acknowledge the long and continued history of medical racism against Black communities before trying to explain away vaccine hesitancy in Black communities as a simple matter of mistrust.

Posts warned against being too quick to “chastise” Black people who were skeptical of the vaccines because they are justified in being reluctant after a long history of medical racism. Other posts underlined the need for science to “right a wrong,” pointing to the case of Henrietta Lacks as another example in which Black people have been exploited by the medical system [65].

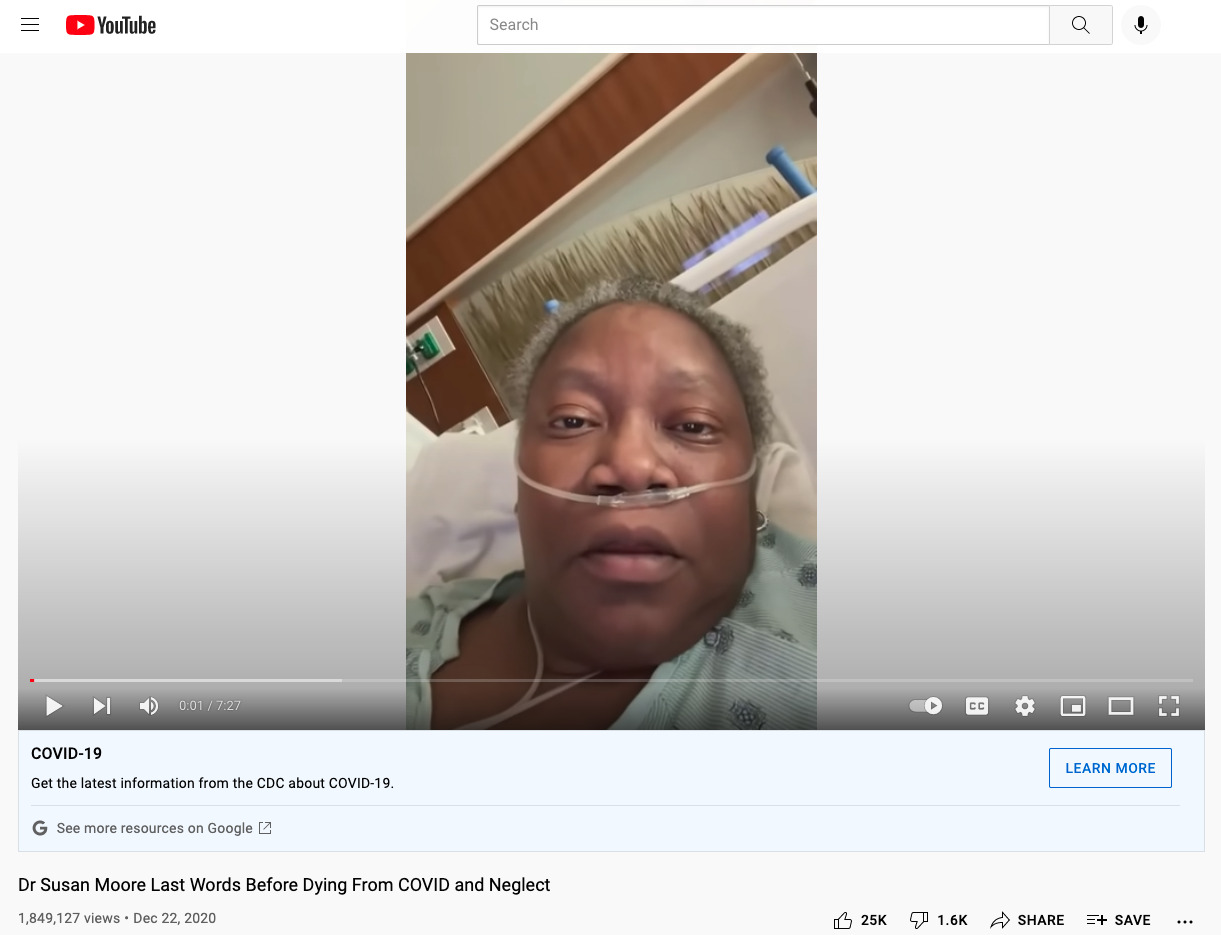

Still more posts supporting this narrative pointed to current racism in the medical system, using the death of Dr. Susan Moore as the latest example of the unequal treatment Black people receive.

Screenshot by authors

Ultimately, the narrative underlines how after years of medical racism and violence it is the responsibility of the medical establishment to gain back the trust of Black people [66]. Given this, it’s unsurprising that many Black people, like other demographics, adopted a “wait and see” approach to Covid-19 vaccines early on — although there are signs this is changing [67] [68]. Many of the most successful efforts at winning the trust of Black communities have come from grassroots campaigns organized by Black activists, community leaders, church groups and health professionals who understand the factors that contribute to decision making around vaccines and the obstacles people in their communities face in getting vaccinated [69]. Yet government and medical institutions have struggled to make vaccines readily available in Black communities [70] [71].

Narrative suggesting the vaccine will be used to depopulate Black communities

Black social media influencers and members of the Nation of Islam have used their platforms to drive the narrative that vaccines are the “white man’s death plan” and that Black people are “guinea pigs” for the Covid-19 vaccine [72].

Misleading narratives claiming the Covid-19 vaccines result in infertility have spread rapidly online, reaching a range of demographics [73]. Accounts linked to members of the Nation of Islam have fed into this; posts from these accounts have claimed, among other things, that the US government under the leadership of then-President Richard Nixon “chemically castrated [Black] males through a vaccine” so that Black men “neither fights nor mates and reproduces.” Those same vaccines, the posts claim, also rendered Black women infertile.

Other posts included videos of Louis Farrakhan — the head of the Nation of Islam — saying that Bill Gates is a “wise satan” who wants to depopulate Blacks around the world.

Screenshot by authors

Narratives claiming government is experimenting on Black people with the Covid-19 vaccine

This narrative seemingly evolved from the many examples of medical malpractice and racism that have affected Black communities historically. The idea that the government was testing the Covid-19 vaccine on Black people was framed as a modern-day version of the Tuskegee experiments — “Tuskegee 2.0.” Testimonials where people claimed to experience extreme adverse side effects after receiving a vaccine, combined with posts questioning why there is such an emphasis on Black people, played into this narrative.

Screenshot by authors

Other well-known white purveyors of vaccine misinformation, such as Simone Gold and Robert F. Kennedy Jr., have taken advantage of Black people’s historical experience of medical racism and fears to sow more distrust around the Covid-19 vaccines in Black communities. In one video shared across social media, Gold suggests that government agencies are running a “covert operation” to test vaccines on Black people.

Screenshot by authors

And in a recent film, Kennedy used historical examples of medical racism to push his own anti-vaccination agenda onto the Black population. Because the history of medical racism and experimentation is still fresh and gross inequalities in healthcare outcomes continue, this narrative remains potent and persistent on social media [74].

Narratives that vaccines are especially dangerous to Black women

Vaccine shedding, according to the CDC, is the “release or discharge of any of the vaccine components in or outside of the body,” and “can only occur when a vaccine contains a weakened version of the virus,” which none of the Covid-19 vaccines administered in the United States do [75].

A report from The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists states that “claims linking COVID-19 vaccines to infertility are unfounded and have no scientific evidence supporting them” and “[that] while environmental stresses can temporarily impact menses, vaccines have not been previously associated with menstrual disturbances” [76].

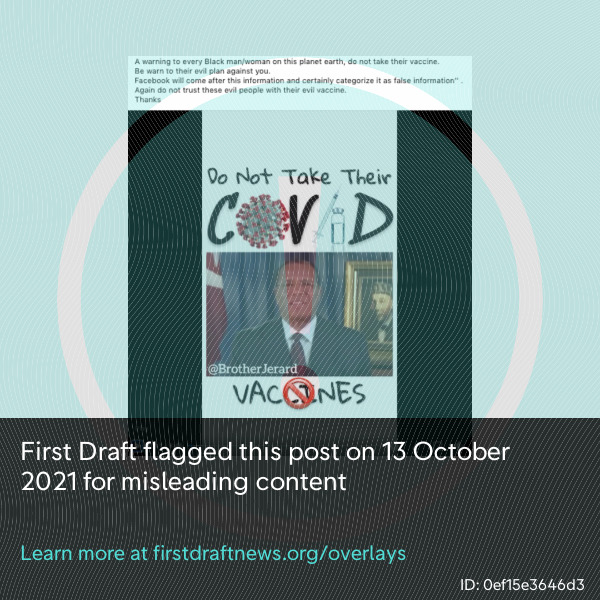

The idea of vaccine shedding and the idea that vaccines can cause reproductive effects on unvaccinated people proliferated among white influencers before the claims migrated into Black communities. Posts made in April from astrological influencer Imani Cohen and singer Summer Walker about vaccine shedding helped spread these claims to majority Black audiences.

Walker and Cohen reshared posts about alleged menstrual irregularities from white anti-vaccine influencers in their Instagram Stories. One post shared by Walker said, “[s]tay the f*ck away from people who are vaccinated. People are reporting: bleeding, bruising, spontaneous periods and miscarriages from being in close proximatey [sic] to a recently vaccinated person.” They also continued to share screenshots on their Stories from people claiming that they had experienced side effects, some from being around vaccinated people.

Screenshot by authors

“[P]pl kill with that ‘stop spreading harmful misinformation.’ Just cause a white man on cnn didn’t say it don’t mean it’s misinformation,” Walker posted.

Johnson & Johnson’s problematic history of marketing its “possibly carcinogenic” baby powder to Black women was also used to advance the idea that vaccines could be more dangerous for Black women [77].

Screenshot by authors

Conclusion

As rates of Covid-19 increase in many areas of the US, closing the vaccination gap within Black communities will be critical to protecting Black lives and preventing the spread of health and economic disparities among the Black population. As more initiatives are launched to reach Black people, understanding the predominant vaccine narratives within Black spaces online will be vital to guiding effective communications strategies aimed at building trust in the available vaccines.

As our research into social media posts from November 9, 2020, to June 9, 2021, showed, sentiments of mistrust of Covid-19 vaccines, of institutions and of the effort to vaccinate Black people were widespread. Mistrust in institutions, driven by inequality, can make populations more susceptible to misleading information and more resistant to reliable information about vaccines. This is particularly problematic where vaccine misinformation is allowed room to spread.

As we show, numerous influencers, many of them Black influencers, have been able to spread anti-vaccination claims with relative impunity over the past seven months. And among the most engaged-with posts we analyzed, we were able to identify myriad misleading and conspiracy theory-related posts that have evaded moderation and remain visible on social media. As social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook provide little in the way of access to aggregate data on moderation, it’s unclear whether the moderation of misleading posts is actioned evenly across demographics. Nonetheless, the continued interaction of mistrust and misinformation will complicate any efforts to increase rates of vaccination.

Yet it’s important to note that identifying the core narratives on social media that may be influencing how Black people perceive Covid-19 vaccines is only one part of a larger toolkit that communications specialists and policymakers should use to redress widespread mistrust among Black communities and close the vaccination gap.

Endnotes

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2021). COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations

2. Ndugga, N., Hill, L. & Artiga, S. (2021). Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

3. Bloomberg. (2021). U.S. Racial Vaccine Gaps Are Bigger Than We Thought: Covid-19 Tracker. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/covid-vaccine-tracker-global-distribution/us-vaccine-demographics.html

4. Ndugga, N., Hill, L. & Artiga, S. (2021). Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

5. Oladipo, G. (2021). Black and Latino communities are left behind in Covid-19 vaccination efforts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/12/black-latino-left-behind-covid-19-vaccines

6. Cancryn, A. (2021). Biden’s vaccine push fails to gain traction with African Americans. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2021/06/07/vaccine-equity-black-americans-biden-491973

7. Hoststetter, M. & Klein, S. (2021). Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust Among Black Americans. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans

8. Faife, C. & Kerr, D. (2021). Official Information About COVID-19 Is Reaching Fewer Black People on Facebook. The Markup. https://themarkup.org/citizen-browser/2021/03/04/official-information-about-covid-19-is-reaching-fewer-black-people-on-facebook

9. Cubbon, S. (2020). Identifying ‘data deficits’ can pre-empt the spread of disinformation. First Draft. https://medium.com/1st-draft/identifying-data-deficits-can-pre-empt-the-spread-of-disinformation-93bd6f680a4e

10. Loomba, S., de Figueiredo, A., Piatek, S., de Graaf, K. & Larson, H. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nature Human Behaviour volume 5, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01172-y

11. Jaiswal, J., LoSchiavo, C. & Perlman, D.C. (2020). Disinformation, Misinformation and Inequality-Driven Mistrust in the Time of COVID-19: Lessons Unlearned from AIDS Denialism. AIDS and Behavior, 24, 2776–2780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02925-y

12. Pierre, J. (2020). Mistrust and Misinformation: A Two-Component, Socio-Epistemic Model of Belief in Conspiracy Theories. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 8(2), 617–641. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v8i2.1362

13. Mendez, R. (2021). Fauci says U.S. must vaccinate more people before Delta becomes dominant Covid variant in America. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/06/08/fauci-says-us-must-vaccinate-more-people-before-delta-becomes-dominant-covid-variant-in-america.html

14. Cubbon, S. (2020). Identifying ‘data deficits’ can pre-empt the spread of disinformation. First Draft. https://medium.com/1st-draft/identifying-data-deficits-can-pre-empt-the-spread-of-disinformation-93bd6f680a4e

15. Loomba, S., de Figueiredo, A., Piatek, S., de Graaf, K. & Larson, H. Measuring the impact of COVID-19 vaccine misinformation on vaccination intent in the UK and USA. Nature Human Behaviour volume 5, 337–348. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01172-y

16. Gould, E. & Wilson, V. (2020). Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus—racism and economic inequality. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/black-workers-covid/

17. Golden, S. (2020). Coronavirus in African Americans and Other People of Color. Johns Hopkins Medicine. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/coronavirus/covid19-racial-disparities

18. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2021). Tracking the COVID-19 Economy’s Effects on Food, Housing, and Employment Hardships. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/tracking-the-covid-19-economys-effects-on-food-housing-and

19. Livingston, C. (2021). Black Americans’ Vaccine Hesitancy is Grounded in More Than Mistrust. Duke Research Blog. https://researchblog.duke.edu/2021/04/08/black-americans-vaccine-hesitancy-is-grounded-by-more-than-mistrust/

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). The U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm

21. Downes, H. (2020). Honouring the slaves experimented on by the ‘father of gynaecology’. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/honouring-the-slaves-experimented-on-by-the-father-of-gynaecology-148273

22. Summers, K. (2021). Systemic Racism & Health Care: Building Black Confidence in the COVID-19 Vaccine. University of Nevada, Las Vegas. https://unlv.edu/news/release/systemic-racism-health-care-building-black-confidence-covid-19-vaccine

23. Bailey, S. (2021). Our Black maternal health crisis is an American tragedy. American Medical Association. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/our-black-maternal-health-crisis-american-tragedy

24. Jimenez, M., Rivera-Nuñéz, Z. & Crabtree, B. (2021). Black and Latinx Community Perspectives on COVID-19 Mitigation Behaviors, Testing, and Vaccines. JAMA Network Open. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17074

25. Roozenbeek, J., Schneider, C., Dryhurst, S., Kerr, J., Freeman, A., Recchia, G., van der Bles, A. & van der Linden, S. (2020). Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. Royal Society Open Science, 7(10). https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201199

26. The University of Auckland. (2021). Thematic analysis | a reflexive approach. The University of Auckland. https://www.psych.auckland.ac.nz/en/about/thematic-analysis.html

27. Smith, R., Cubbon, S. & Wardle, C. (2020). Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation & data deficits on social media. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/vaccinenarratives-report-summarynovember-2020

28. The Economist. (2020). America’s black upper class and Black Lives Matter. The Economist. https://www.economist.com/united-states/2020/08/22/americas-black-upper-class-and-black-lives-matter

29. Romero, L, Salzman, S. & Folmer, K. Kizzmekia Corbett, an African American woman, is praised as key scientist behind COVID-19 vaccine. ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/kizzmekia-corbett-african-american-woman-praised-key-scientist/story?id=74679965

30. Kaur, H. (2020). Fauci wants people to know that one of lead scientists who developed the Covid-19 vaccine is a Black woman. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/12/09/us/african-american-scientists-vaccine-development-trnd/index.html

31. Jones, Z. (2020). Fauci urges Black community to be confident in COVID-19 vaccine: “The time is now to put skepticism aside.” CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/fauci-black-community-covid-19-vaccine/

32. Nuriddin, A., Mooney, G. & White, A. (2020). Reckoning with histories of medical racism and violence in the USA. The Lancet, 396, 949-951. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32032-8

33. Masullo, G., Kilgo, D. & Bennet, L. (2020). News Distrust Among Black Americans is a Fixable Problem. The University of Texas Center for Media Engagement. https://mediaengagement.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/CME-Report-News-Distrust-Among-Black-Americans-is-a-Fixable-Problem.pdf

34. Hyland-Wood, B., Gardner, J., Leask, J. & Ecker, U. (2021). Toward effective government communication strategies in the era of COVID-19. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 8 (30), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00701-w

35. Brunson, E., Buttenheim, A., Omer, S. & Quinn, S. (2021). Strategies for Building Confidence in the Covid-19 Vaccines. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering Medicine. https://www.nap.edu/read/26068/

36. Dan, P. (2021). Historical Trends in the Representativeness and Incomes of Black Physicians, 1900–2018. Journal of General Internal Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06745-1

37. Arthur, R. (2017). Medicine Is Getting More Precise … For White People. FiveThirtyEight. https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/medicine-is-getting-more-precise-for-white-people/

38. Write, A. (2021). Republican Men Are Vaccine-Hesitant, But There’s Little Focus on Them. The Pew Charitable Trusts. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2021/04/23/republican-men-are-vaccine-hesitant-but-theres-little-focus-on-them

39. Stanley-Becker, I. (2021). Johnson & Johnson vaccine deepens concerns over racial and geographic inequities. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/03/01/johnson-and-johnson-vaccine-distribution-disparities/

40. Johnson, A. (2021). Lack of health services and transportation impede access to vaccine in communities of color. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/02/13/covid-racial-ethnic-disparities/

41. Huang, P. (2021). ‘You Can’t Treat If You Can’t Empathize’: Black Doctors Tackle Vaccine Hesitancy. National Public Radio (NPR). https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/01/19/956015308/you-cant-treat-if-you-cant-empathize-black-doctors-tackle-vaccine-hesitancy

42. Frenkel, S. (2021). Black and Hispanic Communities Grapple With Vaccine Misinformation. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/10/technology/vaccine-misinformation.html

43. Larson, H., Jarrett, C., Eckersberger, E., Smith, D. & Paterson, P. (2014). Understanding vaccine hesitancy around vaccines and vaccination from a global perspective: A systematic review of published literature, 2007–2012. Vaccine, 32(19), 2150-2159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.01.081

44. Larson, H., Jarrett, C., Schulz, W., Chaudhuri, M., Zhou, Y., Dube, E., Schuster, M., MacDonald, N., Wilson, R. & the Sage Working Group On Vaccine Hesitancy. (2015). Vaccine, 33(34), 4165-4175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037

45. Lewis, T. (2021). The Biggest Barriers to COVID Vaccination for Black and Latinx People. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-biggest-barriers-to-covid-vaccination-for-black-and-latinx-people1/

46. Faife, C. & Kerr, D. (2021). Official Information About COVID-19 Is Reaching Fewer Black People on Facebook. The Markup. https://themarkup.org/citizen-browser/2021/03/04/official-information-about-covid-19-is-reaching-fewer-black-people-on-facebook

47. Mo. [@motorresx]. (2021). Another example of racecraft: here we see racism (access to resources, in this case the Covid vaccine) conceal itself, then reappear as race (the attitudes that individual Black people have about the vaccine). Twitter. https://web.archive.org/web/20210306145428/https://twitter.com/motorresx/status/1368212939598041100

48. Boyd, R. (2021). Black People Need Better Vaccine Access, Not Better Vaccine Attitudes. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/05/opinion/us-covid-black-people.html?action=click&module=Opinion&pgtype=Homepage

49. Funk, C. & Tyson, A. (2021). Growing Share of Americans Say They Plan To Get a COVID-19 Vaccine – or Already Have. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/science/2021/03/05/growing-share-of-americans-say-they-plan-to-get-a-covid-19-vaccine-or-already-have/

50. Dembosky, A. (2021). No, the Tuskegee Study Is Not the Top Reason Some Black Americans Question the COVID-19 Vaccine. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/news/11861810/no-the-tuskegee-study-is-not-the-top-reason-some-black-americans-question-the-covid-19-vaccine?fbclid=IwAR2amJ7mUWrAt27sZ7v8Uj4gveEX0VrDuMX_v1I5q190pHnJb_kNkVOe2oI

51. Borelli, D. [@deneenborelli]. (2021). So is Mayor de Blasio ushering in a new Jim Crow law in NYC by banning blacks from restaurants via vaccine passports? Twitter. https://web.archive.org/web/20210803152718/https://twitter.com/deneenborelli/status/1422574642619895813

52. Suburban Black Man. [@goodblackdude]. (2021). Vaccine passports are where we draw the line, folks. You can bow out of this fight and submit to tyranny right now if you plan on complying. Twitter. https://web.archive.org/web/20210328194112/https://twitter.com/goodblackdude/status/1376257983726809091

53. Trump Jr., D. [Donald Trump Jr.]. (2021). 1984 Is Here: Vaccine Segregation In New York City. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/DonaldJTrumpJr/videos/362288625501112/

54. Barlow, R. (2021). “Vaccine Passports”: COVID-19 Protection or Discrimination against BIPOC and the Poor? BU Today. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2021/vaccine-passports-covid-19-protection-or-discrimination/

55. First Draft. (2021). Vaccine Misinformation Insights Report: April. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/vaccine-insights-report-one/

56. Johnson, B. (2021). Chris Cuomo Urges Fauci: ‘You Have To Have A Vaccine Passport’. The Daily Wire. https://www.dailywire.com/news/chris-cuomo-you-have-to-have-a-vaccine-passport

57. Mendez, R. (2021). What you need to know about President Joe Biden’s new Covid vaccine mandates. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/10/what-you-need-to-know-about-president-joe-bidens-new-vaccine-mandates.html

58. Larsson, H. & Broniatowski, D. (2021). Volatility of vaccine confidence. Science, 371(6536) 1289. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi6488

59. Chee, V. (2021). Covid-19 vaccines: A leap of faith and the power of trust among Black and Hispanic communities. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/covid-19-vaccines-black-hispanic-communities/

60. Smith, R., Cubbon, S. & Wardle, C. (2020). Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation & data deficits on social media. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/vaccinenarratives-report-summarynovember-2020

61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Selected Adverse Events Reported after COVID-19 Vaccination. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/safety/adverse-events.html

62. Lajka, A. (2020). No record of registered nurse who claims Bell’s palsy after vaccine. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/fact-checking-afs:Content:9915802202

63. Smith, R., Cubbon, S. & Wardle, C. (2020). Under the surface: Covid-19 vaccine narratives, misinformation & data deficits on social media. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/vaccinenarratives-report-summarynovember-2020

64. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2021). KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor: July 2021. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-july-2021/

65. Nature. (2020). Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02494-z

66. Dembosky, A. (2021). No, the Tuskegee Study Is Not the Top Reason Some Black Americans Question the COVID-19 Vaccine. KQED. https://www.kqed.org/news/11861810/no-the-tuskegee-study-is-not-the-top-reason-some-black-americans-question-the-covid-19-vaccine?fbclid=IwAR2amJ7mUWrAt27sZ7v8Uj4gveEX0VrDuMX_v1I5q190pHnJb_kNkVOe2oI

67. Bunn, C. (2021). ‘Getting a clearer picture’: Black Americans on the factors that overcame their vaccine hesitancy. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/getting-clearer-picture-black-americans-factors-overcame-their-vaccine-hesitancy-n1263787

68. Ndugga, N., Hill, L. & Artiga, S. (2021). Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

69. Sun, H. (2021). A new national model? Barbershop offers coronavirus shots in addition to cuts and shaves. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/05/30/barbershop-coronavirus-vaccines/

70. Diamond, D., Keating, D. & Moody, C. (2021). Vaccination rates fall off, imperiling Biden’s July Fourth goal. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/06/06/vaccination-rates-decline-us/

71. Feldman, N. (2021). Why Black And Latino People Still Lag On COVID Vaccines — And How To Fix It. National Public Radio (NPR). https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/04/26/989962041/why-black-and-latino-people-still-lag-on-covid-vaccines-and-how-to-fix-it

72. Mason, J. (2021). The Nation of Islam and anti-vaccine rhetoric. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/articles/the-nation-of-islam-and-anti-vaccine-rhetoric/

73. First Draft. (2021). Vaccine Misinformation Insights Report: May. First Draft. https://firstdraftnews.org/long-form-article/vaccine-misinformation-insights-report-may/

74. Zadrozny, B. & Adams, C. (2021). Covid’s devastation of Black community used as ‘marketing’ in new anti-vaccine film. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/nbcblk/covid-s-devastation-black-community-used-marketing-new-anti-vaxxer-n1260724

75. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Myths and Facts about COVID-19 Vaccines. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/facts.html

76. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccination Considerations for Obstetric–Gynecologic Care. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/covid-19-vaccination-considerations-for-obstetric-gynecologic-care

77. Kirkham, C. & Girion, L. (2021). Special Report: As Baby Powder concerns mounted, J&J focused marketing on minority, overweight women. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-johnson-johnson-marketing-specialrepo/special-report-as-baby-powder-concerns-mounted-jj-focused-marketing-on-minority-overweight-women-idUSKCN1RL1JZ