This research was supported by a grant from the Rita Allen Foundation.

By Vanessa Chee

Overview

As of July 6, just over 182 million American adults had received at least one Covid-19 vaccine dose, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [1]. But vaccine uptake in the US still shows considerable disparities among demographics. Only 39 per cent of Hispanic people [2] have received a dose of Covid-19 vaccine [3]. Among Black people, 34 per cent have received a Covid-19 vaccine [4]. On the other hand, 47 per cent of white people have received a Covid-19 vaccine.

In the US, nearly all Covid-19 deaths occur among the unvaccinated [5]. As the more transmissible Delta variant spreads across the US, vaccination discrepancies are particularly concerning [6]. Vaccine hesitancy, driven in part by Covid-19 vaccine misinformation, has been theorized as one reason for lower vaccine uptake among Black and Hispanic communities [7][8] . Yet relatively little is known about the relationship between misinformation and levels of Covid-19 vaccine uptake among these communities.

Furthermore, few studies have examined the role of misinformation in relation to other factors that may deter vaccination in Black and Hispanic communities. For example, a lack of access to vaccines has been described as a major issue discouraging vaccine uptake in these communities. Community members also express concerns about the safety and side effects of Covid-19 vaccines — concerns exacerbated in large part by mistrust in official institutions and health authorities [10].

The factors influencing vaccine uptake are not static — they vary by context, time and disease. As new variants and vaccines emerge, and government policies change, so too do communities’ concerns about vaccines and reasons to get vaccinated [11]. Constant monitoring to understand the changing concerns of Black and Hispanic communities as well as the factors influencing their decision-making about vaccines will be critical to efforts to close the vaccine gap.

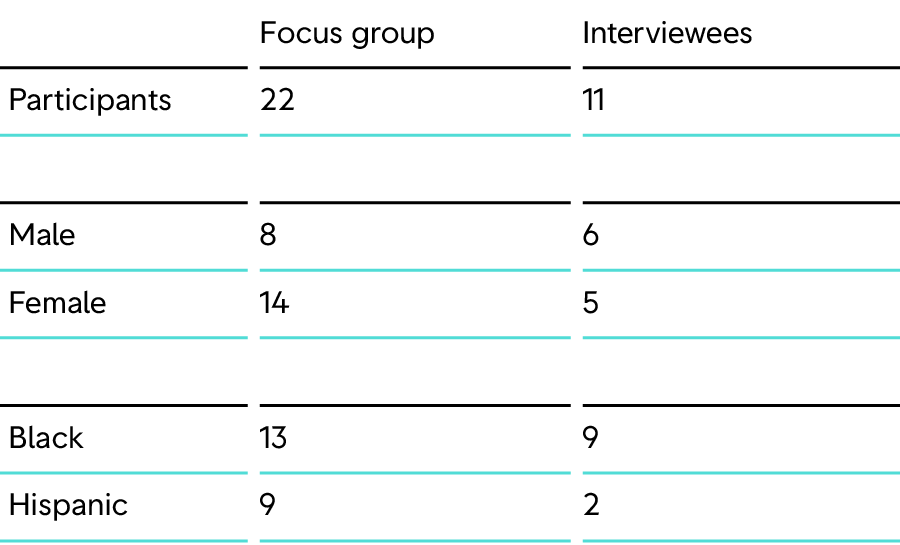

In order to address this knowledge gap, First Draft conducted a qualitative study using in-depth interviews (n=11) and focus groups (n=22) with a total of 33 people from Black and Hispanic communities from April to June 2021. Participants included healthcare professionals, community leaders and health advocates from these communities who were familiar with the issues Black and Hispanic people face in getting vaccinated. Other non-expert participants were also recruited to gain a better understanding of how individuals make decisions about getting a Covid-19 vaccine.

From the research, one central finding stood out: Trust permeates every aspect of the vaccination decision-making process. Getting vaccinated is ultimately an act of trust and a leap of faith, particularly for those who worry about the safety and long-term side effects of Covid-19 vaccines. This leap of faith is particularly large for Black and Hispanic people, given the history of medical exploitation and experimentation that these communities have suffered at the hands of some of the same institutions that are now distributing Covid-19 vaccines. Where trust can be built, higher rates of vaccination are likely. Where trust is low, people will distance themselves from the vaccines, likely adopting a “wait and see” approach. Low levels of institutional trust can also make people susceptible to misinformation, exacerbating concerns about the safety of vaccines and the motivations of the institutions implementing them [12].

Key Findings

Qualitative research is meant to understand people’s experience around a particular phenomenon through collecting and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. While helpful in gleaning insights around the decision-making of people in a particular context or community, for example, qualitative research findings are not easily generalizable. The findings reported here are based on interviews and focus groups conducted with a total of 33 participants from Black and Hispanic communities in the US.

Through this research several key findings stood out:

1) A long history of medical racism and exploitation has left many Black and Hispanic people distrustful of the medical system. For both communities, taking the Covid-19 vaccine represents taking two leaps of faith: 1) believing the vaccines to be safe despite the fact that they are available in the US under emergency use authorization pending full approval by the Food and Drug Administration and 2) trusting the government and the healthcare system have their best interests in mind despite a long history of structural racism, violence and medical exploitation that has shown the opposite.

2) Concerns about the safety and side effects of Covid-19 vaccines were cited as the main reason against vaccine uptake. These concerns were the most widely cited reasons from Black and Hispanic participants for why members of their community are reluctant to embrace Covid-19 vaccines. The belief that the vaccine was rushed, skepticism about the novel mRNA technology, and suspicion about former President Donald Trump’s attempted use of Covid-19 vaccines for political gains contributed to these concerns. These concerns were exacerbated by the underlying lack of trust in the government and the healthcare system.

3) Concerns about vaccine safety have led Black and Hispanic people to adopt a “wait and see” approach to getting vaccinated. Regardless of education, many Blacks and Hispanics are “vaccine deliberate” as opposed to “vaccine hesitant,” electing to wait for further data and evidence supporting the safety of Covid-19 vaccines before choosing to get vaccinated.

4) Young people from Black and Hispanic communities (roughly those ages 20-35) were perceived to be the least informed and most vaccine resistant. Participants described this age group as being the least informed about Covid-19 vaccines and the least likely to seek out credible health information. Instead, this age group preferred to get information from social media and “word of mouth” through friends and family.

5) Misinformation plays a tertiary role in influencing vaccine uptake in Black and Hispanic communities. While participants acknowledged the presence of vaccine misinformation in their families and communities as well as its role in influencing vaccine uptake, they cited vaccine safety concerns as well as structural barriers to vaccines as the main reasons discouraging people from getting vaccinated. However, the role of misinformation should not be overlooked, especially among younger members of Black and Hispanic communities. High levels of mistrust in official institutions can make people more susceptible to misinformation and discourage vaccine uptake.

6) Among those vaccinated, having access to a trusted “health advocate” within the family or community was key to building trust in Covid-19 vaccines. Influential and trusted figures in the community and within family networks who had been vaccinated played a key role in facilitating vaccine uptake among members of the community. The absence of these figures could slow down vaccination efforts.

7) Vaccination sites are often perceived as “deportation traps” by Hispanics. Going to vaccination sites can be frightening for Hispanics. The vaccination booking system can be complex. At times it requires personal information, such as Social Security numbers. Some participants cited lingering fears over previous federal immigration policies. Consequently, requests for personal identification at vaccine sites can fuel fears of deportation, especially among undocumented immigrants.

8) Official public health terminology, such as “herd immunity,” dehumanizes Black communities and can erode efforts at building trust. Couched in the context of a history of medical racism and accentuated by the death of George Floyd, who “was killed like an animal” at the hands of police, said a Black doctor in the study, the term “herd immunity” is fueling further mistrust around vaccination efforts in certain Black communities. Black barbers and stylists in our study, who work to educate their communities about Covid-19 vaccines, adopted the term “community immunity” in discussing the value of herd immunity.

9) Both Black and Hispanic participants reported similar motivations to get vaccinated. Their main reasons included the ability to travel, the desire to protect their household from Covid-19 and the need for a “new normal.” Participants defined their need for a “new normal” as returning to some semblance of pre-pandemic life, where they could attend family gatherings, hug others and socialize.

10) The complexity of the vaccination appointment system threatens efforts by Black and Hispanic people to get vaccinated. Participants from both communities highlighted how an overly complicated appointment system hampered and in some cases deterred vaccine uptake. Many emphasized the number of people who need assistance to navigate the appointment system, particularly the elderly and those whose first language is not English.

This report is divided into five sections:

Background: In this section, we examine how the history of medical and institutional racism has affected Black and Hispanic communities. We also look at how Covid-19 has disproportionately affected these communities, as well as the role of misinformation in discouraging Covid-19 vaccine uptake.

Methods and limitations: In this section, we outline the research methods used to conduct this study, as well as their limitations.

Results: This section provides an in-depth review of study findings. These findings focus on the systemic inequalities experienced by participants, their vaccine concerns and attitudes, and their experience of misinformation as well as its impact.

Discussion: This section relates study findings to the bigger picture of other studies.

Conclusion: In this section, we summarize the key takeaways from the research.

Background

Black and Hispanic people have suffered disproportionately from Covid-19 compared with white populations throughout the pandemic. Reasons for this include structural inequalities, such as food deserts, that worsen pre-existing disparities related to chronic conditions (obesity, diabetes and hypertension) that dramatically affect Covid death rates. Other inequalities are related to income, employment and health insurance. As of June 14, Black people represented only 8.9 per cent of those fully vaccinated in the US. Hispanic people represent 14.1 per cent of the fully vaccinated [13]. Currently, Black and Hispanic people are twice as likely to die of Covid-19 and three times more likely to be hospitalized than their white counterparts. Failing to close the vaccine gap will exacerbate these health disparities and economic inequalities facing Black and Hispanic communities [14], worsening Covid outcomes among them.

Many obstacles remain in the way of closing this gap. As we detail in this report, chief among them are fear of vaccine side effects, along with fear of government and the medical system [15]. Black and Hispanic people have endured years of medical exploitation and racism. Documented exploitation and experimentation on Black communities stretches from the “medical apartheid” that allowed the Tuskegee experiments (1932-1972) [16] to using Henrietta Lacks’ cells (HeLa cells) (1951) [17] for research without her consent and without any remuneration until only recently.

Even before Tuskegee, Dr. James Marion Sims conducted brutal experiments from 1845-1849 on African American slave women without anesthesia to create the surgery repairing vesicovaginal fistula [18]. For years, Drs. Gregory Goodwin Pincus and John Rock tested birth control pills on poor and marginalized Puerto Rican women [19], using pills containing three times more hormones than modern-day pills. Not only were these women not told that they were part of an experiment, but the side effects they experienced were ignored [20].

Very little has been done to redress these historical injustices and rebuild trust among Black and Hispanic communities. These same communities continue to grapple with medical racism and structural inequalities, which only fuel institutional mistrust, a key determinant of vaccine hesitancy [21]. High levels of mistrust in official institutions can make people more susceptible to misinformation [22]. And exposure to misinformation, regardless of whether a person believes it or not, can reduce the likelihood of that person getting vaccinated [23]. A Kaiser Family Foundation survey in April found that nearly 55 per cent of adults either believe some popular bits of Covid-19 vaccine misinformation or are unable to discern whether this misinformation is true or false [24].

While mistrust and misinformation can discourage rates of vaccination intent, there are other factors that can thwart vaccine uptake [25]. For example, the low perceived risks of a vaccine-preventable disease may reduce vaccination rates [26]. Paradoxically, so too does the success of immunization campaigns; the perceived risk of a disease compared with the perceived risks of receiving a vaccine declines as more people get vaccinated [27]. Structural barriers, such as lack of access to vaccine clinics because of inconvenient and hard-to-reach locations, poor public transportation and loss of pay for skipping work to get a vaccine, contribute to lower rates of vaccination.

Mistrust, misinformation and lack of access to vaccines have all been cited as factors discouraging vaccine uptake in Black and Hispanic communities [28]. But the factors curbing vaccine uptake are not static — they vary by context, time and disease. As new variants and vaccines emerge, and government policies change, so too do people’s concerns about vaccines and reasons to get vaccinated. For policy makers, health experts and community leaders working on vaccination efforts for Black and Hispanic people, it’s important to continuously investigate concerns and obstacles in these communities in order to successfully encourage vaccine uptake.

Methods and Limitations

Study Design

For this research, several strands of data — in this case focus groups and interviews — were collected within the same time period (from April to June 2021) [29]. The results were then compiled during data analysis, or the manual analysis and extraction of themes using applied thematic analysis. In this study, focus group and interview findings were integrated and analyzed together using the same codebook in NVivo — a software package used to analyze qualitative data.

This study design was appropriate to this study purpose in that focus groups allowed us to gather insight about vaccine attitudes from the rich cross-talk discussions between Black and Hispanic people as they compared how vaccination was viewed in their respective networks. Interviews allowed key figures such as health professionals to give us insight regarding vaccination attitudes. Data acquired from interviews was different from focus groups; it allowed us to delve into the experience and insight of people who work with and among Black and Hispanic communities, whereas focus groups helped us to understand the perspective of people who identified as Black or Hispanic from a variety of walks of life. This exploratory convergent parallel design with two qualitative strands consisted of:

1) Five focus groups with individuals from different professional backgrounds.

2) Eleven semi-structured in-depth interviews with key figures.

Interviews and focus groups were transcribed, then analyzed in NVivo. We applied thematic analysis [30] to analyze the interviews and focus groups and extract emergent themes until we reached saturation — where no new themes emerged [31]. To analyze transcripts, an NVivo codebook was developed. This codebook was guided by using a priori topics (referred to as nodes in NVivo), in keeping with the method of applied thematic analysis. These a priori nodes were misinformation, vaccine concerns, obstacles to get a vaccine and factors that affected the decision to get a vaccine. Emergent, more granular themes were then added under these general nodes.

Study Sample and Recruitment

Snowball sampling was used to recruit Black and Hispanic participants who work as health professionals, community leaders and journalists. We chose these professions and participants because they have been working in Black and Hispanic communities throughout the pandemic and were familiar with the concerns and obstacles facing these populations. We conducted 11 interviews, with two Black nurses, two Black nursing researchers, one Black clergy member, two Hispanic journalists, one Black editor/nursing researcher, one Black disparities researcher and two Black doctors.

We also conducted five focus groups, which included a total of 22 participants (14 women and eight men). Four of the focus groups were mixed and consisted of nine Hispanic and ten Black participants. Within these four focus groups, four of the Hispanic participants were health professionals and researchers, while there was one Black doctor. The fifth focus group consisted of only Black participants — two barbers and one hair stylist — who were certified community health workers in Maryland and actively involved in the Health Advocates In Research (HAIR) initiative [32].

In an attempt to capture voices from outside the health and journalism professions, we also included several other participants in our focus groups. These lay people included Black community members such as a sports broadcaster, a customer service retail worker, a grocery clerk, a clergy member and a military nurse. There was also a Hispanic Realtor.

Limitations

1) This was a qualitative study that included only 33 participants, many of whom came from specialized backgrounds such as medicine and public health. Time constraints and recruiting challenges complicated efforts to gather a more diverse set of participants. It was also difficult to reach journalists from these communities — one of our original target populations. We therefore pivoted to focus on health experts and community leaders who work on vaccine-related issues in these populations. Furthermore, the ratio of Black to Hispanic participants was not even; there were 22 Black participants compared with 11 Hispanic participants. As a consequence, the results of this study are not generalizable to Black and Hispanic communities in the US.

2) We faced difficulties recruiting unvaccinated individuals. Most of the focus group participants had been vaccinated. Only three participants had elected not to get vaccinated. As a consequence, we relied heavily on the insights of medical professionals and health advocates working in these communities to understand the barriers, including misinformation, hampering vaccine efforts.

3) Most of the study participants had been vaccinated and many others were health professionals or health advocates. We relied on their perceptions as representatives of their respective communities regarding the influence of misinformation on vaccine decision-making. While the barbers and hair stylist we spoke with worked directly with individuals who had concerns about vaccines, some spawned by misinformation, understanding the overall scope of misinformation as well as its power in influencing decisions around vaccines among Black and Hispanic people was difficult to establish. The research would have benefited from having a focus group of only unvaccinated individuals.

Results

In this section we detail the salient themes that emerged from our interviews and focus groups. The themes we gleaned from talks with our participants shed light on the many barriers, both emotional and structural, hampering vaccine uptake among Black and Hispanic communities in the US. We have organized the themes under three categories:

- Mistrust in the medical system

- Media consumption and misinformation

- Vaccine concerns and barriers to vaccination

Mistrust in the medical system

Through our interviews and focus groups it became clear that trust, or lack thereof, is the top factor influencing the decision-making process for Black and Hispanic people about vaccines. Getting vaccinated is ultimately an act of trust and a leap of faith, particularly for those concerned about the safety and long-term side effects of Covid-19 vaccines. According to participants, mistrust in official institutions and the medical system in Black and Hispanic communities translates to skepticism about vaccines generally and lower rates of Covid-19 vaccine uptake by extension. There are many factors that have contributed to the prevalence of mistrust in Black and Hispanic communities in the US. In the following section, we detail some of the main reasons laid out by study participants.

The significance of the “Tuskegee experiments” and the long history of medical abuse within Black populations

The reasons for Black people distrusting Covid-19 vaccines are many, but one important factor contributing to mistrust is the “Tuskegee experiments” and what they have come to represent. Tuskegee was mentioned by every Black person we spoke to in interviews and focus groups.

A disparities researcher explained the legacy of the “Tuskegee experiments.” He suggested that the real harm wasn’t only that white doctors withheld life-saving treatment to study the progression of syphilis among hundreds of Black men and failed to get their informed consent, leaving these study participants unaware of the true nature of the experiment. Rather, the real harm was that this study took place over 40 years and required the ongoing complicity of multiple government bodies in order to withhold treatment.

“That’s the great migration of Black people moving out of the South and moving North that the public health service sent out a message to all the health departments in the country and said to them, ‘Here’s a list. Give them the names of the men in the Tuskegee study. And if any of these men show up, do not treat them.’ 1932 to 1972, guess what? World War II would happen. People were drafted into the Army. And as they came into the Army, they had to do what? They have to get a physical. And if they had flat feet, they didn’t get in. If they have an infectious disease, guess what? They got treated. But the draft boards received a list and said, ‘If any of these men show up, do not treat them. They are in the Tuskegee study.’”

The coordinated and systemic violence these men suffered didn’t happen in isolation. The Black community endured many historical examples of medical racism and exploitation. Participants highlighted other “historical wounds” such as Sims’ brutal experimentation on slaves without anesthesia and, most recently, the deaths of Dr. Susan Moore and George Floyd. Their deaths have disinterred these historical traumas and spotlighted how medical and structural racism continue today. The disparities expert, referencing the death of Moore, tied it together in these words:

“Front Page. New York Times. Black physician takes off her white coat. Removes the stethoscope from around her neck. Puts on a hospital gown. And who is she? She’s just another Black woman. And for her to feel that from her peers that she had to pull out [her phone] and Facebook to America what was happening to her. She used her phone like a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I couldn’t believe it. You know she died…the bottom line is, as a Black physician [Facebooking] the fact that she was being discriminated against and experiencing racism in the hospital, my point to you is that she had enough voice and agency to get her story on the front page of The New York Times. But the folk in the hood, folk in the barbershop, they see that. They see that’s happened to Uncle so-and-so or Auntie so-and-so, or my mother even to them, and they just suck it up. They’re not going to get in the newspaper. So they just avoid the experience if they can unless they have to. And we’re trying to reverse that… it contributes to skepticism of the entire medical enterprise and the clinical trial, biomedical enterprise, and vaccines are all part of that. Be mindful, the two vaccines that are out there of the three are all EUAs, Emergency Use Authorization. They are experimental.”

Throughout its history of exploiting the Black community, the medical system has proven itself to be untrustworthy, said one Black doctor. “That mistrust has been earned,” he said.

The “Tuskegee experiments” were one incident among many others. As participants described, the word “Tuskegee” is both a memory and a symbol; it’s a container that holds all the different acts of historical medical abuse by the government along with the potential of this same abuse happening again. Tuskegee represents the sum of these “historical wounds” as well as current medical abuse.

The “Tuskegee experiments” have become a filter through which health information and the medical system are framed among Black communities in the US and globally. According to participants, it will be difficult to redress these wrongs and establish trust without the government acknowledging its role in perpetuating these acts of medical abuse. “It takes a long time to earn back trust,” said one doctor. In the meantime, continued mistrust in the medical system is likely to continue discouraging vaccination uptake in the Black community.

Lower standards of care and disingenuous interest in Black and Hispanic communities

According to various participants, one factor hampering attempts at earning the trust of Black and Hispanic people in the medical system and Covid-19 vaccines is the unequal treatment and lower standards of care they experience when seeking out health authorities. As mentioned, the death of Susan Moore in December is still fresh in the minds of many and a reminder that health inequalities persist. Various Black and Hispanic participants said they felt that they would not be taken seriously if they experienced serious side effects from the vaccine.

In focus groups, Black and Hispanic women perceived lower standards of care from white doctors as opposed to doctors who share their ethnic identity. They also said they felt less comfortable with white doctors and health professionals. Black and Hispanic women said they feel the need to earn the respect of medical professionals in order to get a standard of care equal to that of their white counterparts. According to participants, white women did not have to contend with this distressing aspect of the healthcare system when they seek medical care.

One Hispanic woman described how “exhausting” it is to deal with racism within the healthcare system and the lower standard of care she says she receives from white doctors:

“Well, yes, I agree because they think bodies are bodies, and bodies are bodies embedded in the culture. Our bodies might work the same way but our desire to get a vaccine or not will depend on that culture and what information is being given to us through that culture…We, as Latino women, we are very much aware that when you go out there, you need to dress it up, right? Because if you go like, we say in Puerto Rico, if you go looking like the maid, they’ll treat you like the maid, right? That is not something that a white woman has to worry about when she goes to her doctor, right? Or when she goes anywhere, she doesn’t have to worry about: Is she wearing sneakers, and a T-shirt, and no makeup?…I had to look for somebody who was Hispanic, who understood my culture. Yes, I had a thyroid problem but he would not even bother. He didn’t think I had anything so why should I? So, it’s just one of those things…”

Other focus group participants expressed concerns over standards of care. One public health professional explained her shock upon discovering that some resident doctors are still trained to believe that black women are immune to pain. Another woman, a layperson from Georgia, expanded on this and how it relates to the pandemic. She said doctors hesitate to prescribe pain medication to Black women, which contributes to the higher risk of traumatic birth experiences and disproportionate rates of infant mortality. She then talked about how this health disparity relates to the Covid vaccine:

“When I was giving birth to my daughter, we both ran into some complications. As far as our health is concerned, like I had a fever and I was in an extreme amount of pain. My doctor, who was not a person of color, brushed it off. If you research it, a lot of women of color die when giving birth, because the providers will ignore our levels of pain. They will think that we’re either faking or lying, or we’re not in as much pain as we say that we are. And something like that could really sway our trust in the healthcare system. Say, if we were to get this vaccine, and we say that we have these symptoms, and then we go to our provider, and our provider doesn’t believe us. So that could really mess with the trust in that sense.”

This same woman provides insight into the connection between quality of medical care and mistrust in the Covid vaccine. She was among the most vocal participants regarding her reasons for mistrusting vaccines in general:

“I would say within the Black community, we don’t really trust vaccines…I’ve seen so many videos of healthcare workers who will openly admit that they’ve been told to not put forth much effort when it comes to people of color, and saving our lives, and giving us the right vaccinations. So that’s why I think within our community, we’re really against getting it right now.”

Other participants mentioned that policymakers continue to neglect systemic health inequalities, such as food and pharmaceutical deserts [33], which contribute to chronic illnesses disproportionately affecting Black and Hispanic communities and aggravating Covid-19 outcomes. The perceived lack of political interest in addressing these inequalities led some participants to say they felt that Covid-19 vaccines were being pushed on their communities in a “jab and go” effort to protect white populations in order to facilitate “herd immunity.”

The continued absence of political will to address these long-term issues, which preceded Covid-19 but have continued throughout the pandemic, fuels mistrust in the motivations of the government to suddenly vaccinate Black communities.

The lack of diversity and representation within medicine

The disproportionately low number of Black and Hispanic healthcare professionals was another factor participants cited as a barrier to trusting the medical system tasked with promoting and administering Covid-19 vaccines.

One doctor, who hosts his own podcast, said:

“There is a representation issue. You need doctors who look like the population, talk like the population to come out and speak to the certain population that you’re trying to target in order for that message to be a little bit more credible. And I think that’s also a part of the problem is, do we have enough African Americans? Do we have enough Latinos? Do we have enough Asian American physicians, pharmacists, other health care professionals who are out there speaking about this issue…?”

This doctor explained how a lack of representation weakens trust in the medical system:

“…when you have individual physicians that actually look like the individuals that we’re trying to gain the trust of, that has helped. It definitely has been a difficult sort of path and journey….I think it’s been helped by Black physicians talking to their Black patients, and just really having an open and honest conversation.”

Official public health terminology, such as “herd immunity,” dehumanizes Black communities and is redolent of slavery

The scarcity of Black and Hispanic representation in the medical system means that much of today’s vaccine lexicon was created and is disseminated by white doctors, health experts and political authorities. Participants pointed out that the specific term “herd immunity” may actually erode efforts to establish trust with Black communities. As a disparities researcher explained, while “herd immunity” is a standard public health term, for many in the Black community, it is dehumanizing and redolent of the language used during slavery and the Jim Crow era.

According to the disparities expert, couched in the context of a long history of medical racism and accentuated by the death of George Floyd, who “was killed like an animal” at the hands of police, the term is fueling further mistrust around vaccination efforts in certain Black communities. For this reason, the Black barbers and stylists in our study who work to educate their communities about Covid-19 vaccines adopted the term “community immunity” in discussing the value of herd immunity. The doctor explained:

“I realized that we’ve got to adjust the language. We have tapped into our jargon, but we haven’t explained it. We don’t appreciate how it might resonate with a community that has truly been seen as less than human. And while it’s the 21st century and 400 years past slavery, the fact of the matter is, George Floyd was killed like an animal. And it was his humanity.”

Media consumption and misinformation

Where levels of mistrust in institutions are high, especially “inequality-driven” mistrust, individuals are not only more vulnerable to the effects of misinformation but also are more resistant to scientific evidence [34][35]. While none of the unvaccinated participants in our study said they had been influenced by misinformation, participants were quick to describe the presence of falsehoods and misinformation spreading both in their communities and within their own families.

While it’s difficult to measure the impact of misinformation using only qualitative data, the observations provided by study participants help us to better understand the role vaccine misinformation plays in Black and Hispanic communities.

In this section, we outline the information diets of different communities, how information is consumed and explain some of the most common misinformation narratives identified by participants.

Information diets

Black and Hispanic participants agreed that there are stark generational differences in how news and health information are consumed, which one Hispanic journalist referred to as “information diets.”

Several participants considered the younger generation (roughly ages 20-35) the most mistrustful and vaccine resistant. Participants said the younger generation relies on TikTok and Instagram for news and information as well as “word of mouth” from friends and other community members about Covid-19 vaccines, rather than credible sources. Another participant, a hair stylist who also works as a certified community health worker, described the information diets of the younger generation as a mixture of Facebook and “word of mouth.” Her task as a stylist and community health worker was to educate her clients with credible health information. One Hispanic participant, a young woman who worked in customer service online, was an exception to this because she had friends who were in medical school. This suggests that the quality of health information this age group gets is related to a connection to health professionals through friends and family.

Older populations, generally considered less resistant to getting vaccines, mostly relied on “legacy news,” such as that from television and radio.

A vaccine-hesitant Black woman who works in retail suggested that source and context are important factors in how people make sense of vaccine information. States that had fewer restrictions during the pandemic, or reopened earlier than other states, created the illusion that Covid-19 wasn’t serious and that vaccines are unnecessary.

“I think it definitely matters when and how you hear about the vaccine. If you hear about it on social media, honestly, I feel like that just adds a lot of confusion. It could intensify the situation more than necessary. When you hear about it, that could play an important role as well. I first heard about the vaccine while I was at work, and I work in a [job] where I have to encounter customers all the time. I come face to face with a lot of people. The people that I come in contact with, they’re very opinionated. So if I hear about it through those customers who are like, “Yeah, these vaccines are coming out,” but I feel like it’s just kind of pointless because we’ve all been that way. Georgia opened up. Because I’m in the state of Georgia. Georgia was one of the first states to open everything back up before anyone else. So it definitely matters how people have heard about it and when they’ve heard about it.”

In all cases, mistrust in the government and medical system seems to determine both the kinds of information people believed as well as the kinds of information they consumed. As a Hispanic journalist explained:

“Among communities of color, I would say that distrust is probably a little bit higher than the baseline, and a lot of that has to do with historical factors. Some of that is probably due to targeted mis- and disinformation as well, but I would argue that historical distrust of the medical community as well as a lack of access or interest in standards-based news or a distrust of standards-based news sources are all playing a role in what I would perceive and what I’ve seen anecdotally as a higher rate of distrust in, say, vaccines or interest in getting vaccines. But I will also say that like other groups when exposed to high-quality information, you begin to see a change when availability in vaccines increases. You do see a change in attitudes, you do see more people probably getting closer to what we would see the baseline of people saying I wanna get a vaccine or I have got the vaccine.”

The lack of Black and Hispanic representation within journalism is also hampering efforts to build back trust in the media and official health information, according to participants, and providing openings for misinformation to flourish. As a Hispanic journalist explained:

“If you’re a person of color, you’re not necessarily seeing yourself reflected in the coverage…your community is maybe not necessarily being targeted by coverage or doing outreach by media, so there becomes a historical distrust of what we would call standards-based news organizations as well. So you combine all of that and you get a very fertile opportunity for misinformation to ripen.”

Similar to how the lack of diversity in medicine hampers efforts to build trust in Covid-19 vaccines, the lack of diversity in journalism may be eroding trust in the media [37] — a key conduit through which many people get health information [38].

According to the clergy member from Florida, other ideas related to the questionable efficacy of the Covid vaccines also circulate within the Black community:

“There have been a lot of conspiracy theories that have emerged. As a result of being motivated out of fear, lack of information, not believing that the information about the vaccine is forthcoming, that they’re not well-informed. As a result of being motivated out of fear, lack of information, not believing that the information about the vaccine is forthcoming.”

Misinformation narratives

The following misinformation narratives were identified by focus group participants and interviewees as fueling suspicion and mistrust about Covid-19 vaccines in their communities.

Misinformation narrative #1: Covid-19 vaccines will be used to control the population and commit genocide

The involvement of Bill Gates and Dr. Anthony Fauci — both of whom are falsely framed as being involved in a global eugenics program — in the vaccine rollout has bred suspicion and mistrust around Covid-19 vaccines, especially within Caribbean Black populations in the US. Other participants expressed how individuals within their communities worry that Covid-19 vaccines will be used to control their population or commit genocide. One participant expressed this view within the Black community with these words: “So it’s an opportunity to cleanse the African-American race with this thing.”

Misinformation narrative #2: Covid-19 vaccines will be used to microchip and track you

Black and Hispanic people expressed that their communities fear that Covid-19 vaccines contain microchips and will be used by the government to control and track people. According to participants, these fears outweighed concerns about contracting Covid-19 for many in their communities. As one described, “I have seen among the Latinos a lot of not so much fear of the disease that they should have, but more fear of being opposed, fear of government trying, like you said, microchipping you.”

Misinformation narrative #3: Covid-19 isn’t dangerous, it’s just like the common cold

The false beliefs that Covid-19 isn’t dangerous or doesn’t exist were present in Black and Hispanic communities, according to participants. Those who believe that Covid-19 isn’t dangerous falsely equate it to other common viruses like the cold and believe that they should be able to live their lives freely: “There are other people who feel like it’s not that big of a deal. So, what’s the problem? I mean, if it’s part of the so-called viruses that come from the common cold, what’s the big deal?”

Misinformation narrative #4: Vaccines cause autism

The long-debunked claim that vaccines cause autism persists within segments of the Black community, participants said. A Black clergy member in the focus group also underlined how Robert F. Kennedy Jr. capitalized on mistrust in the Black community to further entrench this false narrative.

Misinformation narrative #5: A strong immune system will prevent you from contracting Covid-19

A Black doctor interviewee described the existence of the misleading narrative that a healthy immune system will protect you from Covid-19. This belief primarily pertains to the African diaspora of Black communities, explained the doctor, and is especially salient among followers of pseudoscientist Alfredo Darrington Bowman, also known as Dr. Sebi, and members of the wellness community. Sebi, who died in 2016, long championed veganism and natural remedies for a healthy life. The self-proclaimed “healer” maintained that meat compromises your immune system and that vaccines are unnatural and ineffective.

Misinformation narrative #6: “Big pharma” is only interested in profits, not your health

The unsubstantiated claim that pharmaceutical companies in the US are only interested in profit and care little about people’s health has taken root in Black and Hispanic communities. One participant claimed that the motivation of pharmaceutical companies for “rushing to create a vaccine for Covid” was to “make money quicker.” Both Hispanic and Black participants repeatedly described this as the “for-profit” nature of medicine in the US.

Misinformation narrative #7 :The Covid-19 vaccine will make women infertile

Both Hispanic and Black participants cited concerns that Covid-19 vaccines might affect fertility in women. One participant said that some of her family members were worried that the vaccines are “going to mess up your fertility like they did with Tuskegee and all of the prior research things.”

Vaccine concerns and barriers to vaccination

All study participants emphasized that fears about side effects, household risk to the elderly, access to help with navigating the vaccination system, and perceived ability to recover from Covid naturally influenced their decision-making process regarding Covid-19 vaccination. They enumerated specific concerns and barriers to getting a vaccine. In this section, we explore this list. Study participants also acknowledged the presence of misinformation in their communities, as well as its potential impact in discouraging vaccination among those who did not get high-quality, credible health information.

The vaccine concerns raised by participants in the study help us understand why members of these communities might be reluctant to get vaccinated. But participants also described a number of obstacles complicating efforts to get vaccinated.

It should be noted here that there are some differences between the barriers facing Black and Hispanic populations. Black participants talked a great deal about general mistrust in official institutions and the medical system resulting from historical trauma and the continued lack of access to quality healthcare. Mistrust is a barrier in itself, and its knock-on effects can exacerbate concerns about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines, the motivations of the institutions rolling them out and the spread of misinformation.

Hispanic people, on the other hand, appeared to experience more difficulties in accessing the information and institutional resources they needed in a way that made them and their families feel safe.

The safety and side effects of Covid-19 vaccines

According to focus group participants and interviewees, concerns about the safety and side effects of Covid-19 explain, in large part, why many people in Black and Hispanic communities have been slower to embrace Covid-19 vaccines compared with other demographics.

The perception that the development of Covid-19 vaccines was rushed and the mistaken belief that there haven’t been comprehensive clinical studies demonstrating the safety of Covid-19 vaccines have fueled these concerns. As one participant described:

“I actually lean more toward not trusting it because it’s something that was rushed…for them to come out within less than a year, I was like, ‘Wait for a second, either you’ll have already been sitting on a vaccine or this is extremely rushed and people will probably drop like flies.’”

The novelty of both the disease and the mRNA technology used in Covid-19 vaccines has also left some members of the Black and Hispanic communities cautious of possible side effects. The perceived self-aggrandizing motivations of former US President Donald Trump made others distrustful of the safety of Covid-19 vaccines. As a Hispanic journalist explains:

“When the vaccine discussion first started happening in December, [former President Trump] was showing off how soon we will get the vaccine and stuff. Even my dad was like, ‘It’s happening too fast. I’m not sure I would get the vaccine,’ if it happens in the next couple of weeks — which it did. He ended up getting his first dose in December. We got to the hospital but the discussion was like, “It doesn’t seem safe because it happened too fast and Trump was too excited for it.” It’s the qualifications of it like, “Is it a political theater tool?” “Is it because they care about my health and safety?” “Is it because they care about businesses more, and they want people to go shopping again?” “How am I supposed to know the risks? Do I even have the information I need if something happens to me if I get vaccinated because it’s new?”

Unvaccinated participants in the study expressed that they wanted to see more data about the effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines as well as their short- and long-term side effects. This “wait and see” approach has been adopted by both Black and Hispanic people, including highly educated members of these communities. A Black surgeon described this approach as being “vaccine deliberate” as opposed to being “vaccine hesitant”:

“So they’re just being deliberate, they just want to see and know more, they just want to see the data. And they want to be very deliberate about this action that they’re going to do. About putting this novel sort of medicine in their arm, for this novel virus that no one has great experience with. And especially a virus in a pandemic, in which initially, when this virus and pandemic came out, we were told not to do certain things that just flew in the face of common sense, we were told, don’t go buy a mask, don’t go do this.”

Members of the Black community were wary of being “guinea pigs” in an emergency vaccine effort without full FDA approval.

Even among the vaccinated, concerns about side effects of the vaccine remained an unresolved concern. As a Black female participant explained:

“So we have people who believe in the vaccine, and we have people who don’t believe in the vaccine. Then the people who don’t believe in the vaccine are the ones who seem to believe that Covid isn’t real. So it’s just a mix…I did get the vaccine. Yes, absolutely. I had to get it, and I got it. There’s not enough information, there are not enough studies. There won’t be until it’s been around for a while, and that’s fine. That’s how we learn about vaccines, that’s how we get them to work. Unfortunately, everybody who’s getting it right now were, as my dad says, are “guinea pigs,” we don’t know and we won’t know for a while.”

Participants described how members of the medical community have sent mixed messages about the safety of vaccines. According to participants, there are doctors and nurses still refusing to take the vaccine because they believe it was developed too quickly [39] and there is a lack of convincing data about the vaccines’ side effects. The reluctance of some medical professionals to immediately get vaccinated is complicating efforts to build trust around vaccines in Black and Hispanic communities.

There are many reasons for Black and Hispanic concerns about the safety and side effects of Covid-19 vaccines. But surrounding and accentuating each reason is an overarching feeling of distrust in both the government and the medical system stemming from a long history of neglect, exploitation and racism.

As one Black participant described:

“As it relates to the COVID-19 vaccines, it was really a matter of trying to build that rapport of official faith and honesty within the system. And to be honest, within our community, there wasn’t that built-up trust within the medical community, or the medical system, in and of itself for a host of reasons.”

Religious beliefs and concerns

Different religious concerns and beliefs among Black and Hispanic people are also making people resistant to getting vaccinated. A Hispanic woman described that her “very Catholic” mother was reluctant to get a Covid-19 vaccine because she believes it is based on the use of fetal tissue. As she said, “You’re gonna find a lot more objection about getting anything that might have used any fetal tissue, and more of a preoccupation of moral implications regardless of what the Pope may have said.”

Religion also shapes how people understand Covid-19, and consequently how they perceive Covid-19 vaccines. For some, religion is the answer to treating the disease. An African-American woman described the current dialogue in her church.

“They’re [church members] probably viewing [Covid-19] like, ‘I’ll leave everything in God’s hands. If it’s my time to go, it’s my time to go. There’s no point in me wearing a mask or taking a vaccine when it’s something man-made.’”

This submission to the power of God to protect people from Covid-19 was expressed by both Black and Hispanic people. As a Hispanic real estate agent described:

“My younger brother…is extremely into his faith, and into the church. That’s why his decision is not to take the vaccine…I think it’s just he’s immersed in a lot of viewpoints in which they leave things up to God or a higher power to take care, from his perspective… He says if everything comes out OK and [there are] no issues over the next year or two, then he’ll probably go and take it and have his kids take it once they’re eligible. But right now his faith viewpoints are leading him to decide to not take the vaccine.”

Vaccination sites are seen as deportation traps among Hispanics

Going to vaccination sites can be frightening for many Hispanic people. The vaccination system can be complex, and in some instances, vaccine sites such as pharmacies request personal information, such as Social Security numbers or health insurance cards [40]. Two Hispanic participants living in Florida and California said they were asked for their Social Security numbers when booking their vaccine appointments. In California, according to the participant, they also requested health insurance information.

The previous presidential administration’s aggressive immigration policies are still fresh in the minds of many Hispanic people. As a result, requests for personal details for vaccine appointments are fueling fears of deportation and mistrust of Covid-19 vaccines.

As a Hispanic journalist described:

“It’s that the fear of the Covid vaccine is that clinics are just traps for people. If you were undocumented, you would maybe get reported on or something. We were going through Trump and that happened. Someone would go to do the things they’re supposed to do about their status or whatever. They weren’t a citizen but they were doing what they needed to do according to the lawyers or whatever, and then they got arrested or deported.”

Contradictory guidelines about providing documentation in order to get vaccinated have also left many Hispanics suspicious of the vaccine process. The Hispanic journalist went on to explain:

“Also, the other thing that caused mistrust or uncertainty around getting a vaccine is having your health insurance card. Even though [official health information sources] said that you don’t need it, all the forms to make an appointment ask for your info. My mom kept saying, ‘If they don’t care, why do they ask for it?’… I think that just yielded more mistrust or at least hesitancy. It took longer for people who eventually decided to get the vaccine.”

The absence of vaccination role models

Influential figures in the community and within family networks that had been vaccinated played a key role in facilitating vaccine uptake. The absence of these figures could potentially slow vaccination efforts.

Barbers have long occupied a seat of trust in Black communities. The barbers we spoke with exemplified this position of influence. They mentioned that they were therefore able to persuade many of their hesitant clients to get vaccinated. Other focus group participants mentioned that their choice to get vaccinated also encouraged family members to do the same. Within families, when one person got vaccinated, it set an example for others who trust them to follow.

Low health agency and lack of access to a health broker

Both Black and Hispanic participants explained that the inability to navigate the vaccine system was a critical health disparity that could affect vaccine uptake. Health brokers — trusted members of the family or community — connect people to health services that they need. Health agency refers to the ability to use one’s voice to ask questions of doctors, get second opinions and interact with the medical system’s complex world that includes insurance and appointments. Health agency was linked to a strong social network according to participants. This was especially needed by the elderly, who found it difficult to navigate the vaccination appointment system. Health agency was so crucial that both Black and Hispanic participants considered it a health disparity on its own.

As one Hispanic journalist explained, those who lack help accessing health information or making appointments remain at the highest risk of choosing not to vaccinate. Other Hispanic women in focus groups echoed this idea by delineating the importance of their role in making vaccine appointments for elderly parents, many of whom did not speak English. One Hispanic participant suggested that the lack of a health broker who could act as a bridge between Spanish speakers and the appointment system could deter vaccine uptake in vulnerable populations, such as undocumented immigrants and essential workers.

“I think people who just don’t have access to someone who understands their fear and obstacles…I guess sympathizing with whoever wasn’t able to have an advocate to kind of either translate stuff or do something online for them or keep asking questions until they got an answer to help somebody. It does seem for the farmworkers, who have struggled, it’s getting their voices centered about what they actually need…do they ever feel safe to say what they actually need without feeling like they could put their own livelihoods in danger… I think it’s just, ultimately, someone who wasn’t able to advocate for them either to find the answers they needed or be able to go and fill out the forms of the vaccine appointment required to do that. Even at the vaccination sites, I don’t remember at any single point anyone asking, ‘Would you like someone to talk to you in Spanish?’ to my mom.”

Transportation and inconveniently located vaccine sites

Distant vaccination sites and a lack of transportation continue to hamper efforts to encourage vaccine uptake in Black and Hispanic communities. “Instead of having the people come to the vaccination site, there should be pop-ups in every neighborhood. You literally should not have to travel far in order to be vaccinated,” a Black nursing researcher said.

A Hispanic participant said, “I would say you’re not making it easy for me and you should make it easy for me because you know, I can’t take three hours round trip to go get a vaccine…I don’t have that time in my day.”

A stylist went so far as to offer a ride to her clients who wanted to get a vaccine. “A lot of times, people don’t have transportation, especially my clients,” she said.

Another Black nurse described the structural barriers this way: “Why do I have literally a barrier to access as far as transportation to get medical services? …I literally don’t have [a] copay to get there or I don’t have the money to do the copay for the office visit and the medication and I work.”

The lack of paid time off work and childcare

Among Black and Hispanic populations, the lack of paid time off work was another barrier to vaccination efforts. Long travel times to vaccine sites represent significant losses in earned income for many essential workers.

One Hispanic participant described what essential workers, such as farm workers, ask themselves when they consider getting the vaccine: “Can I take off two times from work to go and get this vaccine? Or would it just be better for me to take the one dose? Can I afford that versus those who have more money?”

A lack of access to childcare was another issue participants cited as discouraging efforts by Black and Hispanic women with children to get vaccinated.

Language barriers to accessing health information

All Hispanic participants indicated that language was a formidable hurdle to accessing health information, understanding public health announcements, and getting a vaccine appointment, especially among older people. This was identified as a critical health disparity. The language barrier worked in two ways, according to Hispanic participants: Health announcements were made in English by public officials with a time lag in translation to Spanish, and the vaccine appointment system had few provisions for Spanish speakers. Even one’s non-native English accent was described as a barrier to navigating the vaccination appointment system. As a Hispanic participant explained:

“When you feel equipped to…ask the right questions [about Covid-19 vaccines], is someone there to ask? That interaction is like, am I going to speak to someone who speaks Spanish? Or am I going to speak to someone who’s going to be frustrated with my accent?”

Conclusion

Despite recent trends hinting at an improvement in the equity of Covid-19 vaccine distribution as well as a narrowing of the vaccine gap between Hispanic and white populations, significant disparities still exist [41]. Less than 50 per cent of Black and Hispanic people have received at least one dose of the Covid-19 vaccine in almost all states that are tracking and reporting this data [42]. According to some analyses, these disparities will exist moving forward [43]. As the highly transmissible Delta variant continues to spread across the US, ongoing disparities in vaccine uptake among Black and Hispanic populations means that these populations are at heightened risk of getting Covid-19.

In order to address these gaps with effective policy interventions, it’s necessary to have up-to-date quantitative and qualitative data detailing the concerns and barriers to vaccination. This is especially important given that the reasons for not vaccinating as well as the barriers to vaccination are not static. While this research cannot be generalized across all Black and Hispanic populations in the US — a sample size of 33 participants doesn’t allow for that — we hope that it can offer some insights into the concerns and barriers influencing vaccine uptake within these populations.

The results of this research suggest that trust among Black and Hispanic populations toward official institutions and the medical system remains broken. A general feeling of mistrust, resulting from a long history of racism and medical exploitation that has continued into the present, surrounds Covid-19 vaccines and shapes people’s decision-making about getting vaccinated. Mistrust is also fueled by continued health disparities related to chronic disease in Black and Hispanic communities, who, as a result, suffer worse Covid-19 outcomes.

Mistrust also exacerbates fears regarding the safety and possible side effects of Covid-19 vaccines — a major concern for both Blacks and Hispanics. Ongoing structural barriers to vaccination, such as hard-to-reach vaccination sites, language obstacles and poor interactions with healthcare authorities when help is sought, fuel more mistrust, which in turn aggravates vaccine concerns and further erodes confidence in vaccines.

Trust takes a long time to build, especially in communities where a long history of medical trauma has done little to assuage these fears. The presence of health brokers — individuals who are trusted in their respective networks and who are able to facilitate the flow of quality health information and health services — can contribute to rebuilding trust in the medical system and Covid-19 vaccines. By acknowledging their historical role in previous acts of exploitation as well as by addressing the ongoing inequalities in the medical system, official institutions can more sustainably build back trust among Black and Hispanic communities.

While vaccine misinformation wasn’t deemed a major concern or reason discouraging vaccination, according to participants, they acknowledged the presence of various false and misleading narratives in their families and communities. We should be careful not to use misinformation as a scapegoat and consequently ignore the historical and structural issues that must be addressed in order to establish trust in Black and Hispanic communities and the system that promotes Covid-19 vaccines.

Nonetheless, we can’t ignore the existence of misinformation and the role it may be playing in further eroding trust in Covid-19 vaccines in these communities, especially among the younger cohort, who seek much of their information from social media and their friends. High levels of mistrust, especially when driven by structural inequalities and continued health disparities, can make communities more susceptible to misinformation. Even exposure to misinformation, regardless of whether an individual believes it or not, can reduce the intent to get vaccinated [44].

For Black and Hispanic people, getting a Covid-19 vaccine is a huge leap of faith. It represents a leap of faith not only in the safety of the vaccines, but also in the institutions and administration tasked with developing, administering and promoting them. Where trust remains low, so too will the number of people willing to take that leap.

Endnotes

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021). Covid Data Tracker — COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccinations

[2] According to the Pew Research Center, “In more than 15 years of polling by Pew Research Center, half of Americans who trace their roots to Spanish-speaking Latin America and Spain have consistently said they have no preference for either Hispanic or Latino as a term to describe the group. And when one term is chosen over another, the term Hispanic has been preferred to Latino.” Survey data from the Kaiser Family Foundation we use in the report as well as survey data from the US Census Bureau refer to Hispanic and Latino interchangeably. We acknowledge the distinction between the words Hispanic and Latino/a. We also acknowledge that many Hispanics relate to national origin (Mexican-American, Colombian-American) instead of the broader category of Hispanic/Latino. However, for the sake of consistency in the report we have elected to use only the word Hispanic to represent both Latino and Hispanic people.

[3] Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill L. & Artiga, S. (2021): Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

[4] Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill L. & Artiga, S. (2021): Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

[5] Johnson, C., & Stobbe, M. (2021). Nearly all COVID deaths in US are now among unvaccinated. Associated Press News (AP News). https://apnews.com/article/coronavirus-pandemic-health-941fcf43d9731c76c16e7354f5d5e187

[6] Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill L. & Artiga, S. (2021): Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

[7] Khan, M., Ali, S., Adelaine, A., & Karan, A. (2021). Rethinking vaccine hesitancy among minority groups. The Lancet, 397(10288), 1863-1865. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00938-7

[8] Laurencin, C. (2021). Addressing Justified Vaccine Hesitancy in the Black Community. Journal Of Racial And Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(3), 543-546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01025-4

[9] Feldman, N. (2021). Why Black And Latino People Still Lag On COVID Vaccines — And How To Fix It. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/04/26/989962041/why-black-and-latino-people-still-lag-on-covid-vaccines-and-how-to-fix-it

[10] Sanchez, G. & Peña, J. (2021). Skepticism and mistrust challenge COVID vaccine uptake for Latinos.

[11] Larson, H., & Broniatowski, D. (2021). Volatility of vaccine confidence. Science, 371(6536), 1289-1289. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abi6488

[12] Vidgen, B., Taylor, H., Pantazi, M., Anastasiou, Z., Inkster, B., & Margetts, H. (2021). Understanding vulnerability to online misinformation [PDF]. The Alan Turing Institute. https://www.turing.ac.uk/sites/default/files/2021-02/misinformation_report_final1_0.pdf

[13] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021). Covid Data Tracker — Demographic Characteristics of People Receiving COVID-19 Vaccinations in the United States. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographic

[14] Shippee, T., Akosionu, O., Ng, W., Woodhouse, M., Duan, Y., Thao, M., & Bowblis, J. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic: Exacerbating Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Long-Term Services and Supports. Journal Of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4-5), 323-333. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1772004

[15] Kim, D. (2021). Associations of Race/Ethnicity and Other Demographic and Socioeconomic Factors with Vaccine Initiation and Intention During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.02.16.21251769

[16] Washington, H. (2008). Medical Apartheid The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Penguin Random House.

[17] Skloot, R. (2011). The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Crown.

[18] Ojanuga, D. (1993). The medical ethics of the ‘father of gynaecology’, Dr. J. Marion Sims. Journal Of Medical Ethics, 19(1), 28-31. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.19.1.28

[19] Eig J. (2014). The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution. W. W. Norton & Company

[20] Vargas, T. (2017). Guinea pigs or pioneers? How Puerto Rican women were used to test the birth control pill. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/05/09/guinea-pigs-or-pioneers-how-puerto-rican-women-were-used-to-test-the-birth-control-pill/

[21] Maystadt, J., Hirvonen, K. & Stoop, N. (2021). Low trust in authorities affects vaccine uptake: evidence from 22 African countries. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/low-trust-in-authorities-affects-vaccine-uptake-evidence-from-22-african-countries-161045

[22] Pierre, J. (2020). Mistrust and misinformation: A two-component, socio-epistemic model of belief in conspiracy theories. Journal Of Social And Political Psychology, 8(2), 617-641. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v8i2.1362

[23] University of South Florida (2021). USF researchers release findings from statewide COVID-19 opinion survey regarding vaccine hesitancy and policy. University of South Florida. https://www.usf.edu/arts-sciences/departments/public-affairs/documents/news-items/spa-covid-vaccine-survey-results-2021.pdf

[24] Hamel, L., Lopes, L., Sparks, G., Stokes, M. & Brodie, M. (2021). KFF COVID-19 Vaccine Monitor – April 2021. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-april-2021/

[25] Thomson, A., Robinson, K., & Vallée-Tourangeau, G. (2016). The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine, 34(8), 1018-1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065

[26] MacDonald, N. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161-4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

[27] MacDonald, N. (2015). Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine, 33(34), 4161-4164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036

[28] Oladipo, G. (2021). Black and Latino communities are left behind in Covid-19 vaccination efforts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/12/black-latino-left-behind-covid-19-vaccines

[29] Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. (2007). Editorial: The New Era of Mixed Methods. Journal Of Mixed Methods Research, 1(1), 3-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/2345678906293042

[30] Guest, G., MacQueen, K., & Namey, E. (2011). Applied Thematic Analysis. Sage Publications.

[31] Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

[32] University of Maryland (2021). The Health Advocates In-Reach and Research Campaign (HAIR): Maryland Center for Health Equity. University of Maryland, School of Public Health. https://sph.umd.edu/hair

[33] Pharmaceutical deserts refer to areas that do not have a pharmacy so that it becomes difficult for residents to access the medicines they need. Food deserts refer to communities where affordable fruits and vegetables are hard to access; instead there is a preponderance of fast-food chains, which in turn increases the risk of lifestyle diseases like obesity, diabetes and hypertension in those areas.

[34] Roozenbeek, J., Schneider, C., Dryhurst, S., Kerr, J., Freeman, A., & Recchia, G. et al. (2020). Susceptibility to misinformation about COVID-19 around the world. Royal Society Open Science, 7(10), 201199. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.201199

[35] Jaiswal, J., LoSchiavo, C., & Perlman, D. (2020). Disinformation, Misinformation and Inequality-Driven Mistrust in the Time of COVID-19: Lessons Unlearned from AIDS Denialism. AIDS And Behavior, 24(10), 2776-2780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02925-y

[36] This may be true, but it might also be an example of the third-person effect — where people think misinformation affects other people more than themselves.

[37] Masullo, G., Kilgo, D. & Bennet, L. (2020). News Distrust Among Black Americans is a Fixable Problem. The University of Texas at Austin Center for Media Engagement.

[38] Weber Shandwick (2018). The Great American Search for Healthcare Information. Weber Shandwick & KRC Research. https://www.webershandwick.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Healthcare-Info-Search-Report.pdf

[39] It should be noted that “vaccine developers did not cut corners. Rather, a true global emergency paired with early application of substantial resources made it possible.” The idea that the vaccine was rushed is misleading.

[40] Chen, C. & Jameel, M. (2021). False Barriers: These Things Should Not Prevent You From Getting a COVID Vaccine. ProPublica. https://www.propublica.org/article/false-barriers-these-things-should-not-prevent-you-from-getting-a-covid-vaccine

[41] Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill L. & Artiga, S. (2021): Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

[42] Ndugga, N., Pham, O., Hill L. & Artiga, S. (2021): Latest Data on COVID-19 Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity. Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

[43] Reitsma, M., Artiga, S., Goldhaber-Fiebert, J., Joseph, N., Kates, J., Levitt, L., Rouw, A. & Salomon, J. (2021). Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF). https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/disparities-in-reaching-covid-19-vaccination-benchmarks-projected-vaccination-rates-by-race-ethnicity-as-of-july-4/

[44] Snyder, A. & Fischer, S. (2021). Misinformation is just one part of a vaccine trust problem. Axios. https://www.axios.com/vaccine-hesitancy-misinformation-cba20e80-6871-4ddb-9405-feaa21be77d3.html