This study is part of a series on health misinformation.

Pakistan is one of just two countries where polio is still endemic (Afghanistan is the other). The global initiative to eradicate polio in Pakistan has experienced varying degrees of success, but has been complicated by ongoing distrust in the motives of global health authorities and recent spikes in polio-related misinformation on social media.

In recent years, there have been very positive developments in maximizing the number of children vaccinated against polio. The Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s recent efforts led to polio workers vaccinating over 37 million children across Pakistan, nearing its goal of vaccinating 39 million children under the age of five. However, the nationwide project was stalled on April 27, 2019, after false rumors about the safety of the polio vaccine started spreading on social media, heavily impacting polio eradication efforts on the ground.

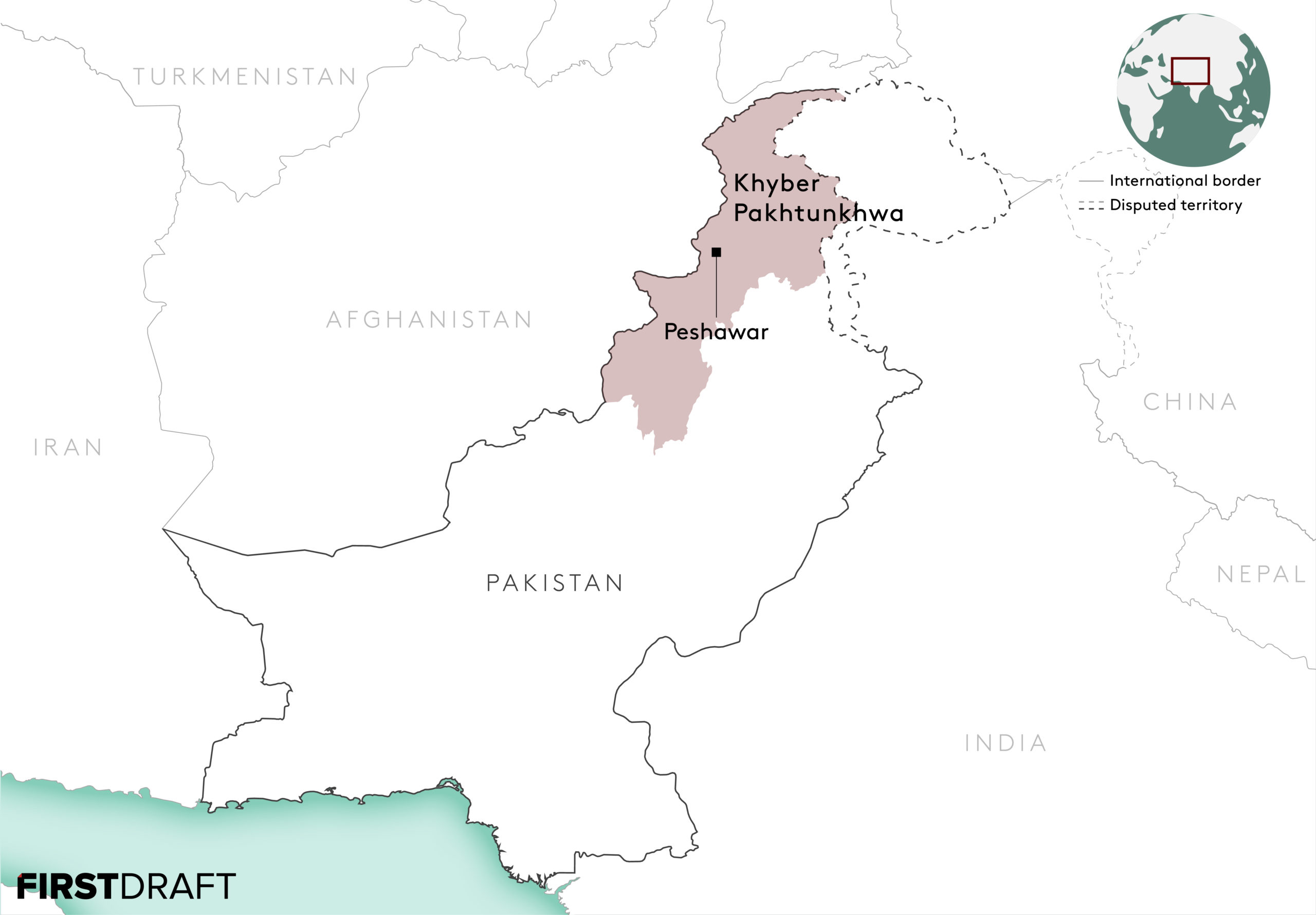

Figure 1: This map shows the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, in northwest Pakistan, where the videos were originated. The base for the map was taken from freevectormaps.com.

This case study focuses on the immediate impact and ongoing fallout from a set of fake videos claiming that children had fallen sick after being administered the polio vaccine. These videos originated in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in northwest Pakistan and spread on social media both within the province and outside of it on April 22, 2019. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has struggled with vaccine acceptance for years, ever since a failed vaccination campaign targeting the province was orchestrated by the CIA in 2011 to obtain Osama bin Laden’s family DNA. As a result, many Pakistanis in the region conflate the polio vaccination with illegitimate and dangerous Western influence in the country’s affairs. Additionally, false rumors that the polio vaccine either contains ingredients forbidden in Islam (such as pork), or toxic ingredients that induce sterilization or make children sick, have circulated for several years.

It was against this backdrop of vaccine hesitancy that a number of misleading videos claiming that children had fallen sick after being administered the polio vaccination went viral. While most of them have since been taken down, reshares of the rumor-related videos received 24,444 Twitter interactions (retweets and likes) within the first 24 hours of their initial posting. As the set of staged videos proliferated across social platforms, they catalyzed the spread of more misinformation. Chaos ensued, and thousands of parents brought their children to Peshawar’s three hospitals in anticipation that they might fall ill. Many other parents refused to vaccinate their children in the following days and weeks. Local mosques broadcasted warnings about the polio vaccine from their loudspeakers. Three people died in the hysteria, and Pakistani authorities suspended Pakistan’s polio eradication campaign five days after the outbreak of misinformation. Since then, over two million children have gone unvaccinated and 144 wild polio virus cases were reported in Pakistan in 2019, compared to a total of 12 cases in all of 2018.

Figure 2: The bar chart shows the total number of polio cases registered in Pakistan since 2015. Source: End Polio.

This case study contextualizes the reasons for vaccine hesitancy in Pakistan, details how the videos spread, and examines the impact they appeared to have on the population of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and other Pakistani provinces with ongoing polio cases. It uses a detailed mining of social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to demonstrate how vaccine misinformation spread. Though social media cannot account for each and every event that unfolded on April 22, and it does not tell the full story of anti-polio vaccine sentiment in Pakistan, it is a useful tool in understanding the messaging of the rumors that spread and the key demographic likely to reshare these rumors across social networks. The case study ends with recommendations for global and national health authorities, as well as for social and search companies.

Overview of events

As a result of the violence and chaos that ensued after April 22, Pakistan suspended its anti-polio campaign on April 27.

While it is impossible to make direct links between the proliferation of online misinformation and anti-polio hysteria on the ground, Figure 1 contains Google Trends data showing the relative popularity of particular search terms between April 19 and April 25, 2019. It reflects a notable spike in the relative frequency of searches for terms related to polio and vaccines in Pakistan on April 22. It would reasonably appear that more people searched for terms related to vaccines and polio immediately after misinformation began circulating.

Figure 3: Google Trends data on the relative search frequency of key terms related to polio and Pakistan between April 19 and April 26, the week of the outbreak of misinformation.

The suspension of the country’s anti-polio campaign was not without consequences. According to the Pakistan Polio Eradication Programme, a total of 144 wild polio virus (WPV) cases were documented in Pakistan in 2019. In contrast, only 12 cases were reported in the country in 2018. 12 cases have been documented thus far in 2020. Ninety-two of the 144 cases reported in 2019 came from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Additionally, over two million Pakistani children have gone unvaccinated in the aftermath of the panic. On July 9, Pakistan announced that it was launching an emergency polio campaign to both get its eradication efforts back on track and address the resurgence of the disease.

Vaccine refusal numbers have skyrocketed since the misinformation incident. In Nowshera, a city in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, vaccine refusals jumped from 256 instances in March to 88,000 in April, Waqar Ahmed Khan, district coordinator at the Youth Catalyst Pakistan (YCP), told Al Jazeera. According to Pakistan’s National Emergency Operations Center Dashboard, there were 990,000 vaccine refusals in all of Pakistan in the month of April.

Figure 4: This map shows the number of polio cases registered in Pakistani provinces in 2019. The highest number of cases appear in the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa where the misinformation campaign spread. Source: End Polio. The base for the map was taken from freevectormaps.com.

On July 9, 2019, Babar Atta, the prime minister’s former focal person for polio eradication, announced that to address the resurgence of the disease, an emergency vaccination campaign would resume from July 15 to July 18 in 12 districts in which polio cases had been discovered. This came after four new cases emerged in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, all of which were attributed to parents’ refusals to vaccinate their children.

On July 21, RFE/RL published an article about Pakistani parents’ latest tactic to refuse vaccines: utilizing fake marker pens. Hesitant parents were marking their children with the same pens used by health workers to indicate that a child has been vaccinated — to avoid actually getting their children vaccinated.

Babar Atta resigned from his position as the head of the polio eradication campaign in Pakistan on October 18, 2019, citing “personal reasons” for his departure in a tweet.

Background

In 2011, the CIA orchestrated a fake Hepatitis B vaccination campaign in the neighborhood in which it suspected Osama bin Laden was hiding: Abbottabad, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. The CIA’s goal in pursuing this drive was to obtain Osama bin Laden’s family DNA samples. According to The Guardian, the CIA’s efforts ultimately failed, and in the aftermath of the incident (especially after the arrest of the doctor who aided the CIA’s endeavor, Shakil Afridi), tensions between the United States and Pakistan worsened significantly. According to a 2015 feature in National Geographic, Afridi is regarded as a traitor in Pakistan, while being “hailed as a hero” in the United States.

The CIA’s botched fake vaccination drive, which was revealed to Pakistanis in 2011, deepened the existing distrust of the polio vaccination campaign among certain Pakistani people. In 2012, a resurgence of polio cases appeared in Peshawar, Karachi, and in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas along Pakistan’s border with Afghanistan, washing away the eradication progress of the early 2000s. In 2013, Leslie F. Roberts of Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health argued that the distrust caused by the CIA’s operation could postpone polio eradication for 20 years.

Ever since the CIA’s operation, the Taliban and other Islamist militant groups have reinforced growing distrust of vaccines with anti-Western rhetoric and utilized anti-vaccination sentiment as a tool in their anti-Western messaging. For example, in June 2012, CNN reported that a Taliban spokesman in northwest Pakistan had announced that health workers, including those distributing polio vaccinations, would be forbidden from operating in North Waziristan, a district in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan, until the United States ended its drone strikes in the region. According to WHO estimates, the June 2012 ban potentially impacted approximately 280,000 children in northwest Pakistan. Militants have also engaged in attacks against health workers distributing polio vaccinations. According to Reuters, militant groups have killed approximately 100 health workers since 2012 on the grounds that they could be “Western spies.”

It is important to note, however, that the Pakistani public is receiving conflicting messages. Certain religious leaders have expressed pro-vaccine sentiments to encourage vaccinations, including religious scholar and senator Maulana Samiul Haq through his issuing of a fatwa that praised the polio vaccination. Known as the father of the Taliban, he encouraged vaccinations in 2013. He died in November 2018.

A vaccinator with kit box, waits for her colleagues, to do an anti-polio campaign in a low-income neighbourhood in Karachi, Pakistan April 9, 2018. REUTERS/Akhtar Soomro

Launched in 1988, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) is an international institutional partnership that has led polio eradication efforts over the past four decades. The initiative is a partnership between the WHO, Rotary International, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, UNICEF, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Gavi, the vaccine alliance. Since its founding, international occurrences of polio have decreased by 99.9 percent. GPEI backs the government of Pakistan in the country’s ongoing battle against polio.

Pakistan’s Polio Eradication Programme is led by the government of Pakistan and is supported, both technically and financially, by GPEI members through the National Emergency Operations Center (NEOC).

Before the April incident, Pakistan’s national government and social media platforms had demonstrated an awareness of the threat posed by online misinformation to Pakistan’s polio eradication campaign. On March 7, 2019, Prime Minister Imran Khan posted a letter on Twitter entitled “Removal of Anti Vaccination Content from Facebook and YouTube.” In the letter, Prime Minister Khan encouraged the social platforms to curb misinformation about vaccinations on their platforms to assist Pakistan in pushing toward complete eradication of polio in the final stages of its vaccination drive.

Response of social and search companies to online vaccine misinformation

In late 2016, primarily in response to the US presidential election, certain social and search companies began to acknowledge the need to counter misinformation on their platforms. They focused primarily on political disinformation and protecting elections. In March 2019, the platforms started addressing vaccine-related misinformation.

Facebook announced its new efforts to tackle vaccine misinformation globally on March 7, 2019, in a press release. In the statement, Facebook said that its strategy toward vaccine misinformation would primarily consist of reducing the ranking of Groups and Pages that spread vaccine misinformation, and rejecting ads that include vaccine misinformation. Facebook also insisted that it would refrain from showing Pages that contain vaccine-related misinformation in Instagram Explore results or hashtag pages. On March 21, Instagram announced that it would begin blocking anti-vaccine hashtags. YouTube also said that it would prevent the monetization of videos that contained vaccine-related misinformation. Earlier in the year, Pinterest purposefully disabled searches for vaccines, preventing users from accessing related information when they search for the term on its platform.

Despite an expressed commitment toward limiting vaccine misinformation content online from both the Pakistani government and social platforms, one of the most pernicious outbreaks of vaccine-related misinformation in Pakistan’s history occurred on April 22, 2019.

Incident

On April 22, 2019, a set of staged videos claiming that children had fallen sick after being administered their polio vaccinations began spreading on social media platforms. According to Dawn, a report published by senior health officials in Peshawar suggested that the videos were posted as part of a preplanned conspiracy against the polio eradication campaign. Much of the misinformation posted on platforms on April 22 has since been deleted, making it difficult to determine where the videos first appeared. (The videos currently still exist on Twitter and Facebook.) On April 22, the videos spread across social platforms, registering at least 24,444 interactions on Twitter within the first 24 hours of being posted. Local news media channels that picked up the story only amplified the rumors.

Figure 5 shows a screenshot from one video that gained a great degree of traction on social platforms and within professional media coverage. In the video, while standing in the Hayatabad Medical Complex, Nazar Muhammad, a private school teacher and resident of the Mashokel area in Peshawar, Khyber Pakthunkhwa, Pakistan, warns viewers that children had begun falling sick after being administered expired polio vaccinations. He then clearly instructs the children surrounding him to fall asleep. Muhammad was arrested on April 22 by Peshawar police for instigating chaos and impeding the vaccination campaign. At least 12 people in total were arrested on April 23 as part of what the provincial health department termed a “coordinated conspiracy to disrupt the polio immunisation drive.”

Figure 5: A screenshot taken from a video of Nazar Muhammad, a private school teacher and resident of the Mashokel neighborhood in Peshawar, Pakistan, who appears in a number of fake videos filmed in the region that proliferated on social platforms on April 22, 2019. The video was reposted in a Tweet from Iftikhar Firdous, a verified Twitter user with 32.2k followers who, according to his Twitter bio, works in Governance & Systems in Pakistan. Iftikhar Firdous attempted to falsify the video, writing: “#Polio vaccination and the kids fainting. Reality vs Agendas.”

Figure 6 is another screenshot from a different video featuring Nazar Muhammad in which he tells reporters in front of a Peshawar hospital that some children had died after being vaccinated.

Figure 6: A screenshot of a video of Nazar Muhammad, a private school teacher who had a major role in proliferating false information about the polio vaccine through staged videos. The video was reposted by @PTIOfficial, the verified Twitter account of Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan’s political party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, which has 4.4 million followers. @PTIOfficial retweeted the video in an effort to falsify it, including the caption: “EXPOSED: Watch carefully how someone was putting words into his mouth regarding the fake and baseless news of deaths due to #Polio vaccination…”.

The spread of misinformation about the polio vaccine caused mass hysteria in northwest Pakistan. On April 22 alone, concerned parents brought a total of 25,000 children to the three hospitals of Peshawar. By the end of the week, that number reached 45,000. Also on the same day, a mob of 500 people set fire to a health clinic in Peshawar.

Over the next week, three people — two police officers and one female health worker — were killed in Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, respectively. Additionally, militant groups and concerned parents all over Pakistan harassed and beat dozens of polio workers with stones throughout the week.

Dr. Shabeer Ahmad, who helps coordinate the polio eradication campaign at the provincial health department of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, told RFE/RL that the addition of Vitamin A to the polio vaccine may have contributed to the rise of the rumor. This is because Vitamin A, which was additionally added to polio vaccines to help malnourished children, can cause symptoms of stomach pain and/or nausea. This may have lent validity to the suggestion that the vaccine itself was making children sick.

On the night of April 22, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s health minister, Dr. Hisham Inamullah Khan, held a press conference in Peshawar in which he said that a preliminary investigation into the vaccines found no evidence that they were unsafe or expired. He pointed to panic as the one and only cause of hospital admittances that day.

Due to the outbreak of violence, Pakistan suspended its anti-polio campaign on April 27.

On May 3, the former head of Pakistan’s polio eradication efforts, Babar Atta, published a letter that urged Facebook to remove vaccine misinformation from its site. On May 10, the platforms — Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter — responded, collectively blocking 174 anti-vaccination links. Facebook blocked 130, Twitter blocked 14, and YouTube blocked 30 links. Additionally, on May 10, Twitter rolled out its vaccines advisory, which is designed to lead users to reputable sources on health information when they search for vaccine-related terms.

The interactive visualisation below shows tweets and Facebook posts which mention the word “polio” in English or Urdu posted between April 19 and April 26 2019. The size of each bubble corresponds to the amount of interactions the post received. Posts containing misleading videos are marked in red, although this does not mean the corresponding account intended to share misinformation. The visualisation does not include posts which have been removed from the platforms.

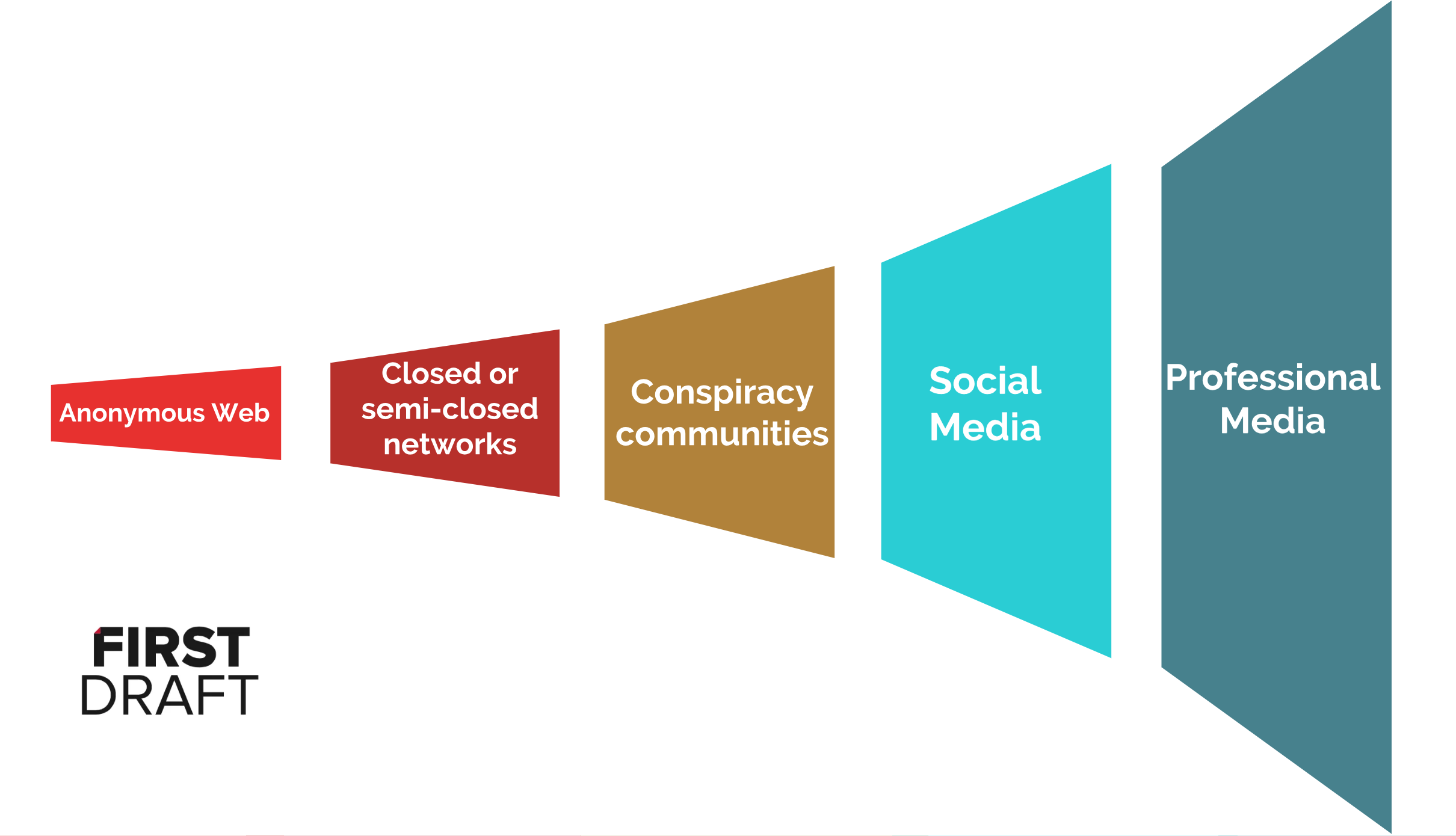

Amplification

To understand what happened in Pakistan, it is essential to recognize the process through which social media often amplifies misinformation [see Figure 7]. Typically, misinformation and rumors begin in closed channels of communication, such as private WhatsApp or Facebook groups. They then spread to conspiracy communities, wider social media platforms, and finally, the professional media. Pakistan’s outbreak of polio vaccine misinformation follows the general pattern of this model, as the misleading videos spread through social media, and then to local news media channels. Ultimately, they were broadcasted from the loudspeakers of mosques by people who urged caution against “poisonous” polio drops.

Figure 7: The Trumpet of Amplification, created by Claire Wardle. This is a useful visualization for understanding how misinformation is amplified as it spreads from closed channels of communication, to open networks and professional news media.

Methodology

Historical data on engagements and interactions from January to June 2019 was collected by automatically collecting posts that contained keywords and hashtags related to polio. Crowdtangle was used to collect Facebook, Instagram and Reddit posts, while the Python programming language was used to automatically collect tweets from the Twitter Search API. The sample was based on the CrowdTangle database. In our data analysis, we focused on calculating keyword frequency spikes over time and analyzing top retweeters and posts that gained high interactions. We defined interactions as the total number of likes, reactions, shares, and comments on a Facebook post; the total number of retweets and likes on a tweet; the total number of likes and comments on an Instagram post; and the total number of upvotes and comments on a Reddit thread.

The screenshots of popular posts and videos that appear in the case study were collected during qualitative data analysis using advanced search features on Twitter and Facebook, CrowdTangle impressions on tweets and Facebook posts (not accounting for posts made in private/closed groups), and through basic search functions on YouTube and Instagram. Our data collection focused primarily on Facebook and Twitter, but we also searched Instagram, YouTube, Google, and Reddit for misinformation. We also suspect that a significant amount of misinformation was disseminated through WhatsApp, from which we could not obtain data because the platform is encrypted.

Two important methodological points to note are as follows:

- Since so many of the posts that originally gained traction on social media and search platforms on April 22, 2019, have since been deleted by the platforms (notably, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter), it is impossible to get accurate numbers for engagement data or to locate the original source of the fake videos. Therefore, data on the posts that received the most interactions is based on the posts that are still active on social platforms. The posts that have been deleted by the platforms are not included in that aspect of data analysis. Additionally, posts made in private or closed Facebook groups are not included as part of the analysis. Thus, there may be more hidden Facebook posts that are still live, but untraceable.

- Many of the hashtags that appeared commonly in anti-polio vaccine posts on social platforms did not yield much data when our data analysis was done. Most of the data we collected was obtained by searching for content that featured the word “polio” and its Urdu translation, and then filtering the results using word combinations related to Pakistan to analyze them.

Data collection and analysis

This section will provide quantitative and qualitative data analysis on Twitter usage on April 22 in Pakistan.

In our data analysis, we scraped tweets containing the keyword “polio” in English and Urdu within a six-month time frame (from January 26 to June 26, 2019), and came up with 11,000 original tweets, excluding retweets. Almost half of these 11,000 tweets contain the word “Pakistan” as well.

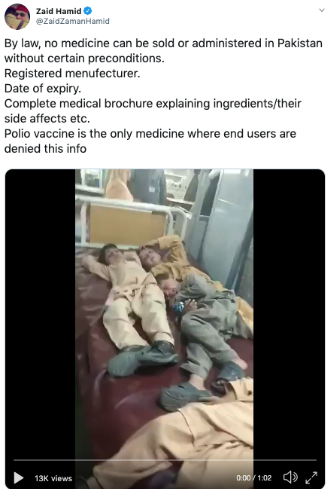

Figure 8: This tweet was posted by @ZaidZamanHamid, a verified Twitter user and a Pakistani political commentator with 300K followers on the platform at time of writing. The tweet received 460 retweets and 881 likes.

Since not everyone specifies a location when they tweet, and we were unable to collect tweets from a specific geotagged location ourselves, we may have missed some tweets from Pakistan that mentioned the term “polio” without also mentioning “Pakistan” or other keywords. Geolocated tweets account for only a small percentage of total tweets.

In the immediate 24 hours after the initial post, original tweets that shared the fake videos (either pushing the narrative that the vaccine was dangerous or debunking the claim) reached a total of 24,444 interactions between likes and retweets.

Based on CrowdTangle historical data, the first tweet posted on April 22 about the rumor appears in Figure 9. It was uploaded at 8:16 am UTC and authored by the local news organization Dunya News. The tweet had low engagement, only receiving three retweets and eight likes.

Figure 9: The tweet was uploaded by Dunya News, a verified Twitter account with 1.7 million followers. It links to this article, last updated by Dunya News at 5:01 p.m. on April 22, 2019.

The first tweets about the rumor that gained relatively high traction on the platform came from Iftikhar Firdous, a pro-vaccine user and former journalist who works in government, and ARY News, a prominent Pakistani news organization. They appear below in Figures 10 and 11 and were tweeted at 9:42 am UTC and 1 pm UTC, respectively.

Figure 10: This tweet was authored by Iftikhar Firdous, a verified Twitter user who works on the polio eradication effort in Pakistan with 32.2K followers. According to his Twitter bio, Firdous works in “Governance & Systems” in Pakistan. The Tweet received 266 retweets and 373 likes.

Figure 11: A tweet posted at 1pm UTC by @ARYNEWSOFFICIAL, a verified Twitter account with 2 million followers that belongs to ARY News, a Pakistani news channel.

By 1 pm UTC, professional news outlets in Pakistan were sharing misleading stories about the rumor.

One particularly influential Twitter user who was among the first to share the rumor about children falling sick is Zaid Hamid, a verified Twitter user and a Pakistani political commentator with 300K followers on the platform at time of writing.

Hamid tweeted numerous times about polio on April 22, 2019, and his most popular tweet appears below in Figures 12.

Figure 12: A tweet posted by Zaid Hamid, who has over 270K followers, at 8:31 am UTC on April 22, 2019, that shows pictures of an ARY News broadcast. The tweet received 648 retweets and 1.2K likes.

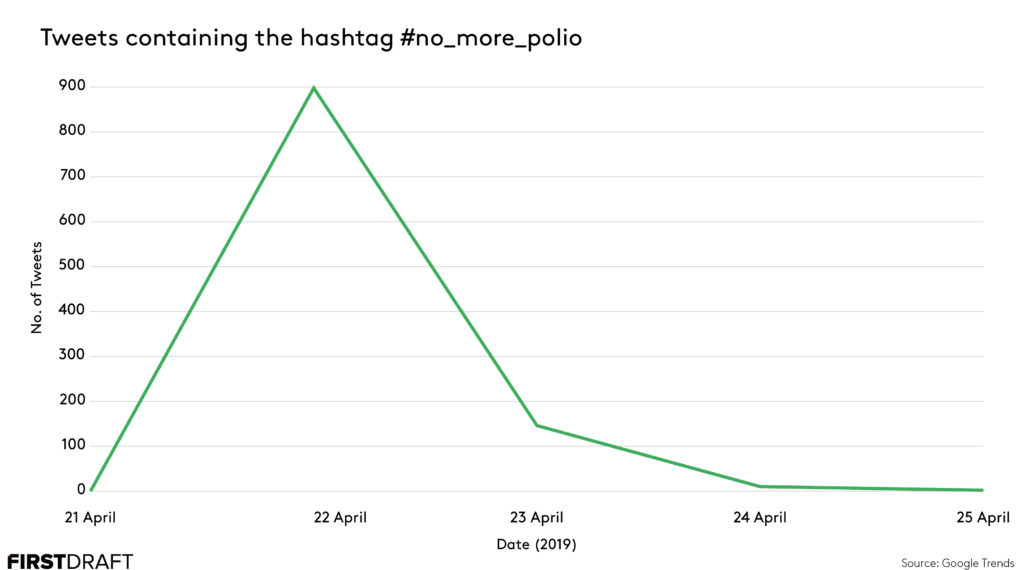

Our analysis of other hashtags on Twitter found there was a spike in the frequency of polio-related hashtags on the platform on April 22, but overall numbers remained relatively low. For example, we found 1,000 tweets containing the hashtag #no_more_polio between April 22 and 25, but the occurrence of the hashtag went down afterward.

Figure 13: Total number of tweets containing the hashtag #no_more_polio on each day between April 21 and April 25.

What’s interesting about Pakistan’s hashtag usage is that all four hashtags most commonly used to spread anti-polio vaccine messages appear to be pro-vaccine in nature. However, hashtags like #no_more_polio actually express resistance to the polio vaccine, not the disease of polio itself.

Based on the data we collected by scraping Twitter keywords and hashtag information, we do not believe that hashtags played a major role in amplifying the rumors. Rather, on Twitter, the sources amplifying the rumor appear to be Pakistani news organizations and pro-vaccine figures who gave an audience to the rumor by sharing articles and videos about it.

This section will provide quantitative and qualitative data on the usage of Facebook on April 22 in Pakistan, which amplified misinformation about the polio vaccine.

Using CrowdTangle historical data, we collected total mentions of “polio” on Facebook in a six-month time frame — from January 26 to July 26, 2019 — gathering 25,012 Facebook posts as a result. From these, we filtered posts directly mentioning “Pakistan” (5,813), “Peshawar” (1,077), “drop” (1,164 ), and the Urdu translation for polio ( پولیو ) (850).

We analyzed the level of user engagement, defined by CrowdTangle as the total number of likes, reactions, shares, and comments on posts, to polio-related posts on Facebook from January 2019 to July 2019. We noted a clear spike on April 22 and in the following days as shown above.

In the immediate 24 hours after the videos were created, public posts that shared the fake videos (either pushing the narrative that the vaccine was dangerous or debunking the claim) reached a total of 990,493 interactions between likes and shares.

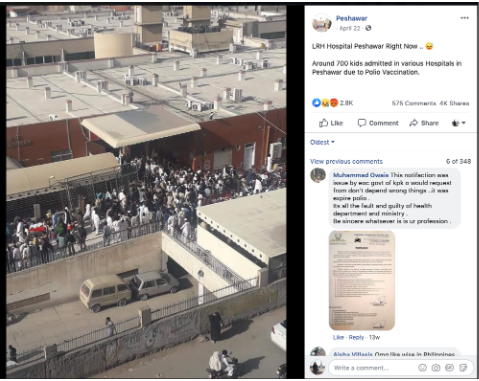

Figures 14 and 15 are the Facebook posts that received the most interactions, according to CrowdTangle data. Figure 15, the most-interacted-with post, was shared by a Peshawar community page, while Figure 16, the second-most-interacted-with post, was shared by ARY News, the same professional Pakistani news outlet that tweeted about the rumor at 1 pm UTC on April 22 (Figure 9). Figure 16 shows a screenshot from a reshared video that was published on YouTube on April 13th, 2017, about polio vaccinations in Pakistan.

Figure 14: The post mentioning both polio and Pakistan with the most total interactions on Facebook on April 22. The post was shared by Peshawar, a community page with over 780,000 likes on Facebook. The post was uploaded on April 22 and received 2,800 reactions, 4,000 shares, and 575 comments.

Figure 15: The post mentioning both polio and Pakistan with the second most interactions on April 22. It was shared by ARY News, a Pakistani news outlet with 15.9 million likes on Facebook. It received over 7,000 interactions. The video the post reshares comes from a 2017 televised report.

Figure 16 is a screenshot from a video shared on Facebook on April 22 which gained traction before being removed. It was viewed over 280,000 times, according to AFP Fact Check. The caption, translated from Urdu, reads: “Children are being given poison in the shape of polio vaccination. Today in Peshawar more than 70 children died and at least another 700 were affected.” AFP Fact Check debunked the claim, stating that the video in the post is from a 2017 television report in Pakistan News Room, a program broadcasted by BOL Network, about polio vaccinations in Pakistan.

Figure 16: A Facebook post containing an outdated video of a televised report from 2017. It has since been deleted, but was viewed over 280,000 when it was first posted.

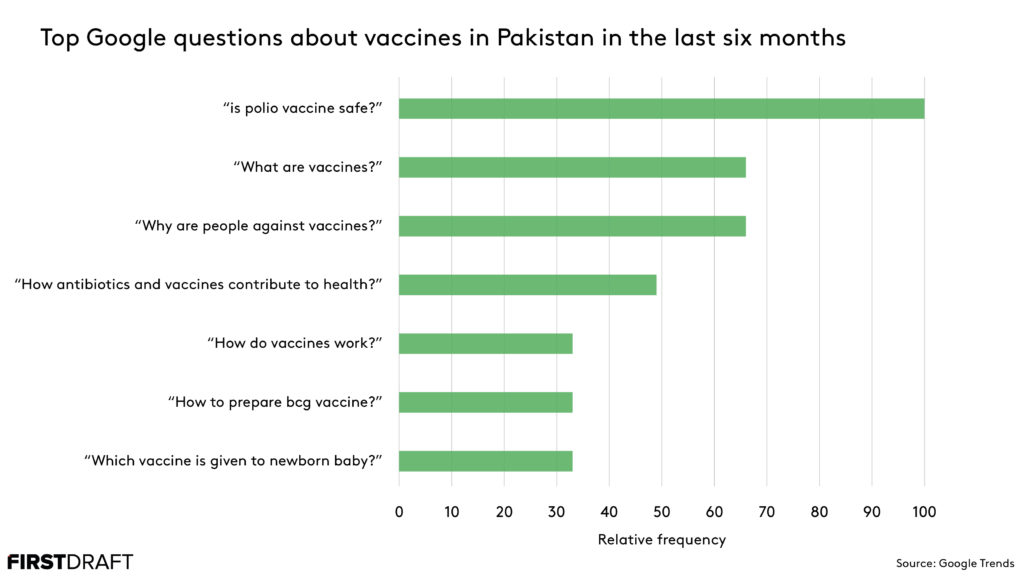

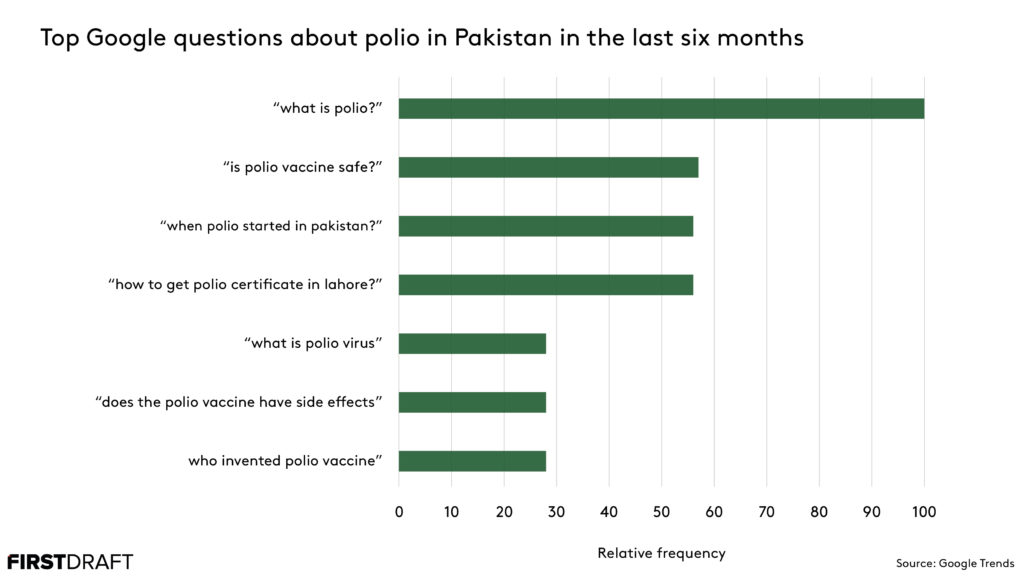

To aid our research, Google shared Indexed Search Interests for several search queries that originated in Pakistan relating to the terms “polio: and “vaccine” over the past six months.

The tables that appear in Figures 17 and 18 contain the Indexed Search Interests that Google shared with us.

Figure 17: This bar graph shows indexed search data concerning the relative frequency of Google searches related to vaccines within Pakistan over the past six months. The most commonly searched question was: “Is polio vaccine safe?”

Figure 18: This bar graph shows indexed search data concerning the relative frequency of Google searches related to polio within Pakistan over the past six months. The most commonly searched question was: “What is polio?”

The second most popular question that appears in Figure 19 is particularly noteworthy in relation to the misinformation about the polio vaccine: “Is polio vaccine safe?”

Also interesting are the sixth and seventh most commonly searched questions related to polio: “Does the polio vaccine have side effects?” and “who invented polio vaccine?” The high frequency of searches of the seventh question in particular demonstrates a lack of understanding among Pakistani citizens about the origin of the polio vaccine.

Formats and messaging

Nazar Muhammad’s staged videos catalyzed the spread of other formats of misinformation on April 22 across social media platforms and professional news sites. From conducting this analysis, the key themes in messaging that emerged across all platforms include: a focus on the vaccines’ effects on children, anti-Western and “War on Islam” sentiments, a lack of faith in government systems, and gunpoint vaccinations.

Illustrating the effects on children

One of the most effective anti-vax strategies is to focus on the immediate effects of a vaccination on a child. Posting images of rashes or a child looking listless or ill utilizes the credibility of personal experience. In this context, reporting on the purported effects on children was common.

Figure 19 is a Facebook post that contains pictures of children who allegedly had reactions to the polio vaccine and were in “miserable conditions.” Officials in Peshawar reported that no child out of the 25,000 who had been brought to hospitals was kept overnight for observation. Though this particular post received relatively low levels of engagement, it is an example of the kind of messaging that allowed the false rumor that children had fallen sick after receiving the polio vaccine to proliferate.

Figure 19: The Facebook post was uploaded by The bkmcite, a Page with 110 likes and listed as a “medical school” that links to this official website. The post is tagged with Hayatabad Medical Complex Peshawar as its location. This particular post received one like and one comment.

Figure 20 shows a tweet (translated from Urdu to English) that links to a misleading report, which contains a video from a televised story posted initially on April 13, 2017, by the Pakistani professional news organizations ARY News. The tweet reiterates the rumor that 700 children had died or fallen ill after being vaccinated. Throughout the course of the day, varying numbers about the exact number of children who had allegedly fallen sick were shared in social media posts, pointing to clear confusion, chaos, and a lack of evidence to substantiate the claims.

Figure 20: A tweet posted by @viaEyes, a Twitter user with 2K followers, that was written originally in Urdu. The tweet reposts a video taken from an April 2017 televised report by ARY News with a misleading caption that does not correspond to the information in the report. Though this tweet received relatively low levels of engagement, with only 17 retweets and 18 likes, it is just one example of the kind of content that proliferated on social platforms on April 22.

Figure 21 is a screenshot from a YouTube video posted by HUM News, a professional news channel in Pakistan. The video had received more than 21,000 views at the time this report was published. Additionally, a common format of messaging throughout the day was to repost YouTube videos on Facebook.

Figure 21: HUM News is a verified content creator on YouTube with 180K subscribers that significantly contributed to amplifying the rumor that hundreds of children had fallen sick after being given the polio vaccine with this video posted on April 22, which received over 20K views on the site.

Figure 22 is an Instagram post with a screenshot of an article originally uploaded by New York Daily News. The post claims that 230-plus children were suffering from nausea following their vaccinations, though that statistic is never mentioned in the article.

Figure 22: An Instagram post authored by the user @i_am_a_soldiers_voice, whose account has approximately 4.8K followers on the site and contains numerous posts with anti-vaccine content.

Within this particular format of messaging, another prominent theme emerges: amplification of the rumor by professional media. Figures 19, 20, and 21 all contain references to reporting done by official Pakistani news outlets, whose credibility in the eyes of Pakistani people potentially lent validity to the false rumors.

Anti-Western sentiment, “War on Islam,” and lack of faith in government

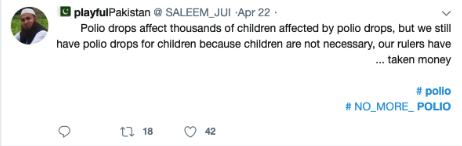

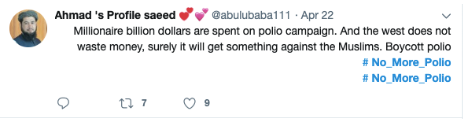

Figures 23, 24, and 25 show three tweets, all translated from Urdu, that were posted in Pakistan in the week following the April 22 incident. They discuss skepticism of the government’s ability to administer safe polio vaccines, as well as vaccinations in general as an attempt to “get something against the Muslims.”

Figure 23: A tweet posted by the user @SALEEM_JUI on April 22, 2019. The user, based in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, has 10K followers on Twitter and posted several tweets on April 22 about the polio crisis in Peshawar with #no_more_polio, a hashtag that received relatively high numbers of interactions in comparison to others.

Figure 24: A tweet posted by the user @abulubaba1111 on April 22 that has since been deleted.

Figure 25: A tweet posted on April 25 by @AMNPeshawar, a media organization with 2.6K followers on Twitter whose official website is linked here. The tweet appears to quote the video it includes.

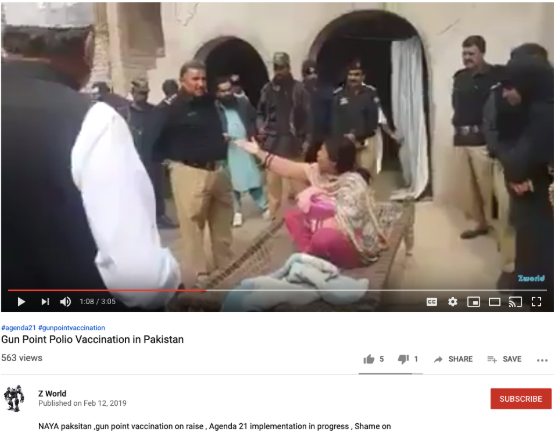

Gunpoint vaccinations

Many social media posts included images of polio vaccinators being assisted by armed police officers, whose jobs involve ensuring the vaccinators’ safety, especially given that attacks targeting polio vaccinators are fairly common in Pakistan. The posts inaccurately conflate the weapons in the photograph with the idea of government oppression, suggesting, without basis, that polio vaccinators force parents into vaccinating their children.

Figures 26 and 27 show examples of gunpoint vaccination messaging that gained traction on social platforms before, during, and after the April 22 outbreak of misinformation.

Figure 26: This tweet was posted on April 23 by user @IamOryaMaqbool, whose Twitter bio characterizes him as a columnist, anchor, Islamist, and scholar. His account is followed by 4,500 Twitter users, and this particular tweet received 25 retweets and 42 likes.

Figure 27: This YouTube video was posted by the user “Z World” on February 12, 2019. Though it was posted two months before the incident in April, it demonstrates anti-polio vaccine messaging about the forcefulness of health workers in distributing polio vaccinations. In the video, which received 572 views, the woman is never actually held at gunpoint. However, the misleading caption disseminates gunpoint vaccination messaging.

Responses from government figures

Given the speed with which the fake videos gained traction on social media platforms, key figures within the Pakistani government served as the “first responders” to the outbreak of the rumor. In certain instances, the content produced by these governmental officials generated relatively high levels of engagement at times.

For example, the tweet that appears in Figure 6 posted by @PTIOfficial, or Prime Minister Imran Khan’s political party, Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, attracted 1,400 retweets and 3,200 likes. The tweet reshared the initial fake video of Nazar Muhammad with the caption “EXPOSED: Watch how young innocent kids were made to lay down in hospital beds and pretend they’re suffering due to Polio vaccination, to give a wrong message to masses regarding the #Polio campaign; SHAME on such people who’re playing with the future of Pakistan ! #Peshawar.”

Two key figures in the Pakistani polio eradication initiative, Iftikhar Firdous and Babar Atta, also used Twitter to respond to the outbreak of the rumor.

Firdous, who is involved in the End Polio Now campaign in Pakistan, posted three tweets that attracted more than 500 interactions on April 22, 2019. Firdous is a verified Twitter user with a following of 32,300 users. In the most popular of the three tweets, Firdous reshared the original fake video of Nazar Muhammad with the caption “#Polio vaccination and the kids fainting. Reality vs Agendas.” Firdous’s message was retweeted 523 times and liked 815 times.

Babar Atta, the former head of Pakistan’s polio eradication initiative, also used Twitter as a rapid response tool on April 22 and in the week that followed. Atta has a Twitter following of 17,000 users. One of his tweets appears in Figure 28. The post contains a video of Nazar Muhammad in jail and sends a message that the Pakistani government would not tolerate deliberate hindrances to its polio eradication efforts.

Figure 28: A tweet posted by Babar Atta containing a video of Nazar Muhammad, the figure who appeared in the initial fake video, in jail. The post was retweeted 719 times and liked 1.9K times.

Pak Fights Polio, the official Twitter account of the Pakistan Polio Eradication Initiative, tweeted numerous times on April 22. Its post with the most interactions appears in Figure 29. It was retweeted 76 times and liked 216 times, but still failed to attract more than 500 interactions total.

Figure 29: The most-interacted-with tweet authored by Pak Fights Polio, the official Twitter account of the Pakistan Polio Eradication Initiative. The account has 5.7K followers.

It is important to note that these tweets were posted by key figures within the Pakistani government. Babar Atta served as a focal member of Prime Minister Imran Khan’s communications team during his election, and even now remains a close aide of the prime minister. Since many of the key figures involved in Pakistan’s polio eradication campaign are associated directly and indirectly with Prime Minister Imran Khan’s political party (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf), it is sometimes suggested that the goal of polio eradication has become politicized, being carried out almost exclusively by the prime minister’s party. For example, in an article published in The Diplomat, Dr. Rana Safdar, former national emergency operations coordinator of the Polio Eradication Program in Pakistan, explains how the polio eradication initiative seems as though it is PTI’s exclusive project, and is no longer a “collective effort.” In the same article, Farhad Jarral, a “social media expert and digital consultant,” alleges that the polio eradication campaign is focused on “promoting the personal gains” of Babar Atta.

Recommendations

The Pakistan incident should be seen as a critical event from which platforms, health authorities, and other actors can learn. Understanding what happened in Pakistan in April could potentially allow us to handle similar situations more effectively in the future.

We suggest that the platforms release the archive of posts and accounts that have been blocked, demoted, or removed to health authorities, researchers, and journalists after an outbreak of misinformation. Tracking the origin and the true spread of the misinformation was extremely challenging, since many of the posts that originally had the most interactions have since been deleted. However, for the purposes of understanding how to stem the growth of rumors, it is essential that health authorities and journalists have access to these materials.

We also suggest that local professional news outlets be trained in best practices for social media content management. Much of the amplification of the rumors that occurred happened because of professional media outlets sharing videos with misleading or underdeveloped captions and reporting. This can be avoided through training seminars in verification and responsible reporting.

In projects connected to monitoring and debunking rumors associated with elections, having coordinated responses from newsrooms, fact-checkers, and other expert groups can slow down the false or misleading content. See evaluations of these types of projects in France and Brazil.

A third takeaway is that images and videos seem to have had the most impact on eliciting emotion-driven action in Pakistan. To mitigate the spread of explosive visual content, we suggest monitoring visual misinformation more closely, perhaps using the AI capabilities of Google’s DeepMind.

Our final note is to suggest that platforms, specifically Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube, work together to combat the spread of cross-platform misinformation. In order to stem the spread of viral misinformation, platforms should develop a cohesive strategy that enables them to take down the same sources of misinformation as quickly as possible.

Research and analysis by Sarika Bhattacharjee and Carlotta Dotto

Graphics by Pedro Noel, Ali Abbas Ahmadi and Carlotta Dotto

Illustration by Rebecca Hendin

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by subscribing to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.