We live in an age of information disorder.

The promise of the digital age encouraged us to believe that only positive changes would come when we lived in hyper-connected communities able to access any information we needed with a click or a swipe. But this idealized vision has been swiftly replaced by a recognition that our information ecosystem is now dangerously polluted and is dividing rather than connecting us.

Imposter websites, designed to look like professional outlets, are pumping out misleading hyper-partisan content. Sock puppet accounts post outrage memes to Instagram, and click farms manipulate the trending sections of social media platforms and their recommendation systems. Elsewhere, foreign agents pose as Americans to coordinate real-life protests between different communities, while the mass collection of personal data is used to micro-target voters with bespoke messages and advertisements. Over and above this, conspiracy communities on 4chan and Reddit are busy trying to fool reporters into covering rumors or hoaxes.

The term ‘‘fake news” doesn’t begin to cover all of this. Most of this content isn’t even fake; it’s often genuine, used out of context and weaponized by people who know that falsehoods based on a kernel of truth are more likely to be believed and shared. And most of this can’t be described as ‘‘news.” It’s good old-fashioned rumors, it’s memes, it’s manipulated videos, hyper-targeted ‘‘dark ads” and old photos re-shared as new.

The failure of the term ‘‘fake news” to capture our new reality is one reason not to use it. The other, more powerful reason is because of the way it has been used by politicians around the world to discredit and attack professional journalism. The term is now almost meaningless, with audiences increasingly connecting it to established news outlets such as CNN and the BBC. Words matter and for that reason, when journalists use the term ‘‘fake news” in their reporting, they give legitimacy to an unhelpful and increasingly dangerous phrase.

Agents of disinformation have learned that using genuine content — reframed in new and misleading ways — is less likely to get picked up by AI systems.

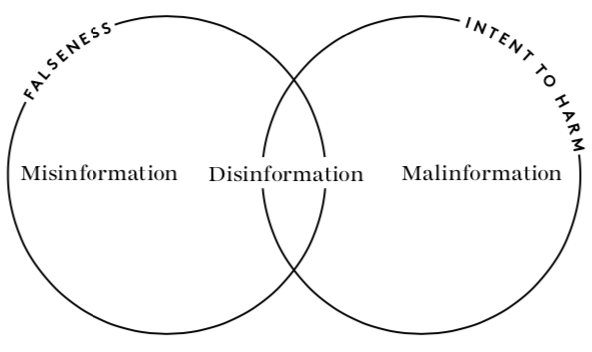

At First Draft, we advocate using the terms that are most appropriate for the type of content — propaganda, lies, conspiracies, rumors, hoaxes, hyper-partisan content, falsehoods or manipulated media. We also prefer to use the terms disinformation, misinformation or malinformation. Collectively, we call it information disorder.

Disinformation, misinformation and malinformation

Disinformation is content that is intentionally false and designed to cause harm. It is motivated by three factors: to make money; to have political influence, either foreign or domestic; or to cause trouble for the sake of it.

When disinformation is shared it often turns into misinformation. Misinformation also describes false content, but the person sharing doesn’t realize that it is false or misleading. Often a piece of disinformation is picked up by someone who doesn’t realize it’s false and that person shares it with their networks, believing that they are helping.

The sharing of misinformation is driven by socio-psychological factors. Online, people perform their identities. They want to feel connected to their ‘‘tribe,” whether that means members of the same political party, parents who don’t vaccinate their children, activists concerned about climate change, or those who belong to a certain religion, race or ethnic group.

The third category we use is malinformation. The term describes genuine information that is shared with an intent to cause harm. An example of this is when Russian agents hacked into emails from the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign and leaked certain details to the public to damage reputations.

We need to recognize that the techniques we saw in 2016 have evolved. We are increasingly seeing the weaponization of context and the use of genuine content — but content that is warped and reframed. As mentioned, anything with a kernel of truth is far more successful in terms of persuading and engaging people.

This evolution is also partly a response to search engines and social media companies becoming far tougher on attempts to manipulate their audiences. As they have tightened up their ability to shut down fake accounts and changed their policies to be far more aggressive against fake content (i.e., Facebook via its Third-Party Fact-Checking Program), agents of disinformation have learned that using genuine content — but reframed in new and misleading ways — is less likely to be picked up by AI systems. In some cases, such material is deemed ineligible for fact checking.

Therefore, much of the content we’re seeing would fall into this malinformation category — genuine information used to cause harm.

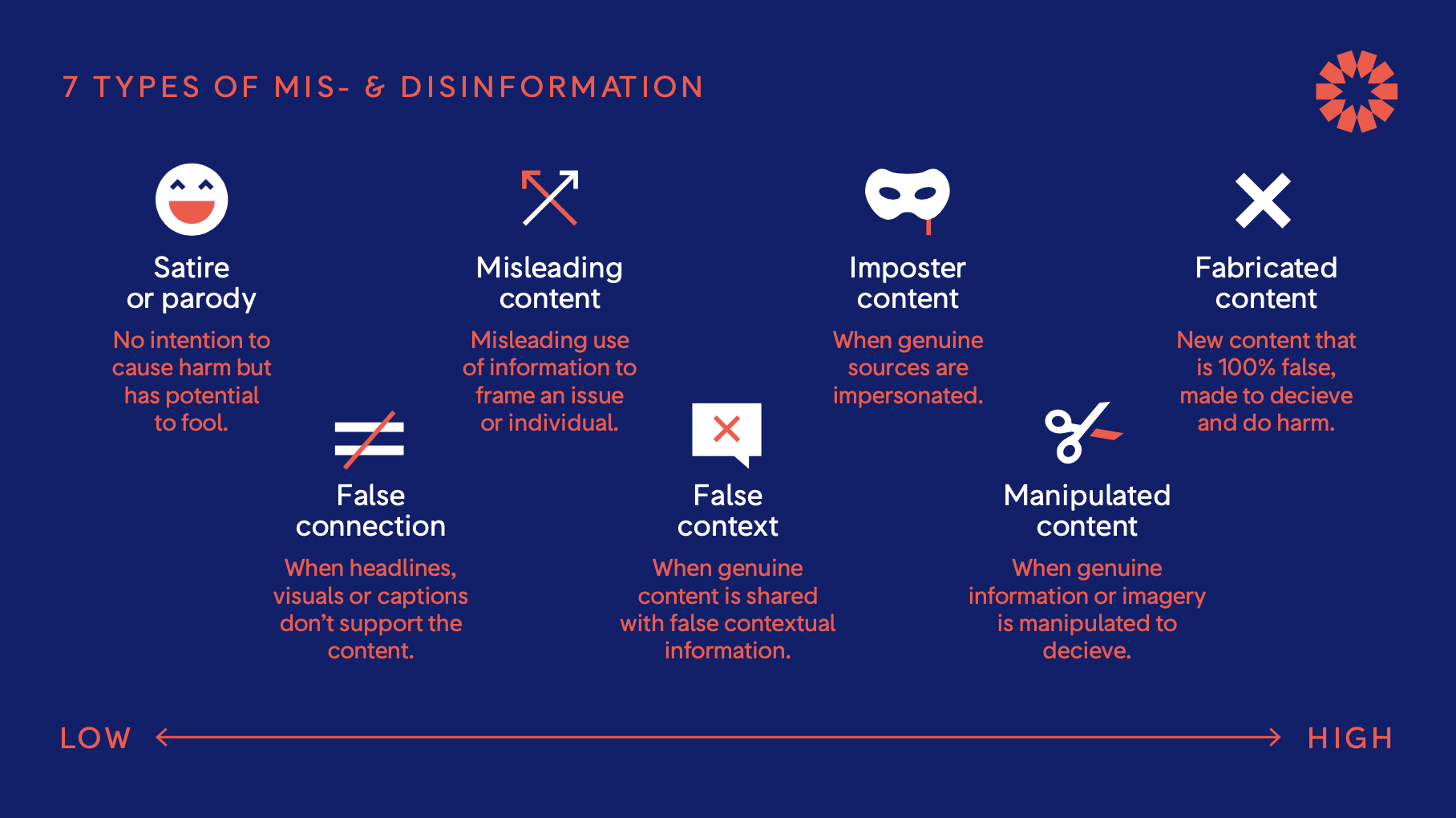

Seven types of mis- and disinformation

Within these three overarching types of information disorder, we also refer frequently to seven categories, as we find that it helps people to understand the complexity of this ecosystem.

They were first published by First Draft in February 2017 as a way of moving the conversation away from a reliance on the term ‘‘fake news.” It still acts as a useful way of thinking about different examples.

As the previous diagram shows, we consider this to be a spectrum, with satire at one end. This is a potentially controversial position and one of many issues we will discuss over the course of this report, through clickbait content, misleading content, genuine content reframed with a false context, imposter content when an organization’s logo or influential name is linked to false information, to manipulated and finally fabricated content. In the following chapters, I will explain each in detail and provide examples that underline how damaging information disorder has been in the context of elections and breaking news events around the world.

Satire or parody

When we first published these categories in early 2017, a number of people pushed back on the idea that satire could be included. Certainly, intelligent satire and effective parody should be considered forms of art. The challenge in this age of information disorder is that satire is used strategically to bypass fact checkers and to spread rumors and conspiracies, knowing that any pushback can be dismissed by stating that it was never meant to be taken seriously.

Increasingly, what is labeled as ‘‘satire” is hateful, polarizing and divisive.

The reason that satire used in this way is so powerful a tool is that often the first people to see the satire often understand it as such. But as it gets re-shared, more people lose the connection to the original messenger and fail to understand it as satire.

On social media, the heuristics (the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of the world) are missing. Unlike in a newspaper where you understand what section of the paper you are looking at and see visual cues that show you’re in the opinion section or the cartoons, this isn’t the case online.

In the US, for example, you might be aware of The Onion, a very popular satirical site. But how many others do you know? On the Wikipedia page for satirical sites, 60 are listed as of September 2020, with 21 of those in the US. If you see a post re-shared on Facebook or Instagram, there are few of these contextual cues. And often when these things are spread, they lose connection to the original messenger very quickly as they get turned into screenshots or memes.

In France, in the lead-up to the 2017 election, we saw this technique of labeling content as ‘‘satire” as a deliberate tactic. In one example, written up by Adrien Sénécat in Le Monde, it shows the step-by-step approach of those who want to use satire in this way.

PHASE 1: Le Gorafi, a satirical site, ‘‘reported” that French presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron feels dirty after touching poor people’s hands. This worked as an attack on Macron as he is regularly characterized as being out of touch and elitist.

PHASE 2: Hyper-partisan Facebook Pages used this ‘‘claim” and created new reports, including footage of Macron visiting a factory, and wiping his hands during the visit.

PHASE 3: The videos went viral, and a worker in another factory challenged Macron to shake his ‘‘dirty, working class hands.” The news cycle continued.

A similar situation transpired in Brazil, during the country’s election in October 2018. In fact, Ethel Rudnitzki wrote a piece examining the sharp spike in Twitter accounts in Brazil using puns related to news organizations and high-profile journalists. They described the accounts in their bios as parody, but as Rudnitzki demonstrated, these accounts were used to push out false and misleading content.

A 2019 case in the US involved a Republican political operative who created a parody site designed to look like Joe Biden’s official website as the former vice president was campaigning to be the Democratic nominee for the 2020 presidential election. With a URL of joebiden.info, the parody site was indexed by Google higher than Biden’s official site, joebiden.com, when he launched his campaign in April 2019. The operative, who previously had created content for Donald Trump, said he did not create the site for the Trump campaign directly.

The opening line on the parody site reads: “Uncle Joe is back and ready to take a hands-on approach to America’s problems!” It is full of images of Biden kissing and hugging young girls and women. At the bottom of the page a statement reads: “This site is political commentary and parody of Joe Biden’s Presidential campaign website. This is not Joe Biden’s actual website. It is intended for entertainment and political commentary only.”

Some of the complexities and tensions around satire and parody played out as part of a public online dispute between the Babylon Bee (whose tagline reads: “Your Trusted Source for Christian News Satire”) and Snopes (an established debunking site). Snopes has “fact checked” the Babylon Bee a few times — on the first occasion fact checking the story headlined, “CNN purchases industrial-sized washing machine to spin news before publication.”

More recently, Snopes fact checked a Babylon Bee story with the headline, “Georgia lawmaker claims that a Chick-fil-A employee told her to ‘go back’ to her country” — suggesting that in the context of a tweet by President Trump aimed at four new congresswomen to “go back home,” the satirical site may be twisting its jokes to deceive readers.

The genuine and parody Joe Biden websites are almost indistinguishable at first glance. Retrieved August 14, 2019. Screenshot and text overlay by First Draft.

In a November 2018 Washington Post profile of renowned hoaxer Christopher Blair, the complexities of these issues surrounding satire are explained.

Blair started his satirical Facebook Page in 2016 as a joke with his liberal friends to poke fun at the extremist ideas being shared by the far right. He was careful to make clear that it was a satirical site and it included no fewer than 14 disclaimers, including, “Nothing on this page is real.”

But it kept becoming more successful. As Blair wrote on his own Facebook Page: “No matter how racist, how bigoted, how offensive, how obviously fake we get, people keep coming back.” Increasingly, what is labeled as “satire” is hateful, polarizing and divisive.

As these examples show, while it might seem uncomfortable to include satire as a category, there are many ways that satire has become part of the conversation around the way information can be twisted and reframed and the potential impact on audiences.

False connection

As part of the debate on information disorder, it’s necessary for the news industry to recognize its own role in creating content that does not live up to the high standards demanded of an industry now attacked from many sides. It can — and does —lead to journalists being described as the ‘‘enemy of the people.”

I want to highlight practices by newsrooms that can add to the noise, lead to additional confusion and ultimately drive down trust in the Fourth Estate. One of these practices is ‘‘clickbait” content, which I call ‘‘false connection.” When news outlets use sensational language to drive clicks — language which then falls short for readers when they get to the site — this is a form of pollution.

“While it is possible to use these types of techniques to drive traffic in the short term, there will undoubtedly be a longer-term impact on people’s relationship with news.”

It could be argued that the harm is minimal when audiences are already familiar with the practice, but as a technique it should be considered a form of information disorder. Certainly, we’re living in an era of heightened competition for attention when newsrooms are struggling to survive. Often, the strength of a headline can make the difference between a handful of subscribers reading a post and it breaking through to a wider audience.

Back in 2014, Facebook changed its new feed algorithm, specifically down-ranking sites that used clickbait headlines. Another update in 2019 detailed how Facebook used survey results to prioritize posts that included links users had deemed more “worthwhile.” A study conducted by the Engaging News Project in 2016 demonstrated that “the type of headline and source of the headline can affect whether a person reacts more or less positively to a news project and intends to engage with that product in the future.”

The need for traffic and clicks means that it is unlikely clickbait techniques will ever disappear, but the use of polarizing, emotive language to drive traffic is connected to the wider issues laid out in these guides. While it is possible to use these types of techniques to drive traffic in the short term, there will undoubtedly be a longer-term impact on people’s relationship with news.

Misleading content

Misleading information is far from new and manifests itself in myriad ways. Reframing stories in headlines, using fragments of quotes to support a wider point, citing statistics in a way that aligns with a position or deciding not to cover something because it undermines an argument are all recognized — albeit underhanded — techniques. When making a point, everyone is prone to drawing out content that supports their overall argument.

A few years ago, an engineer at a major technology company asked me to define “misleading.” I was momentarily flummoxed because every time I tried to define the term I kept tripping over myself, saying, “Well, you just know, don’t you? It’s ‘misleading.’”

Misleading is hard to define exactly because it’s about context and nuance and how much of a quote is omitted. To what extent have statistics been massaged? Has the way a photo was cropped significantly changed the meaning of the image?

This complexity is why we’re such a long way from having artificial intelligence flag this type of content. It was why the engineer wanted a clear definition. Computers understand true and false, but misleading is full of gray. The computer has to understand the original piece of content (the quote, the statistic, the image), recognize the fragment and then decipher whether the fragment significantly changes the meaning of the original.

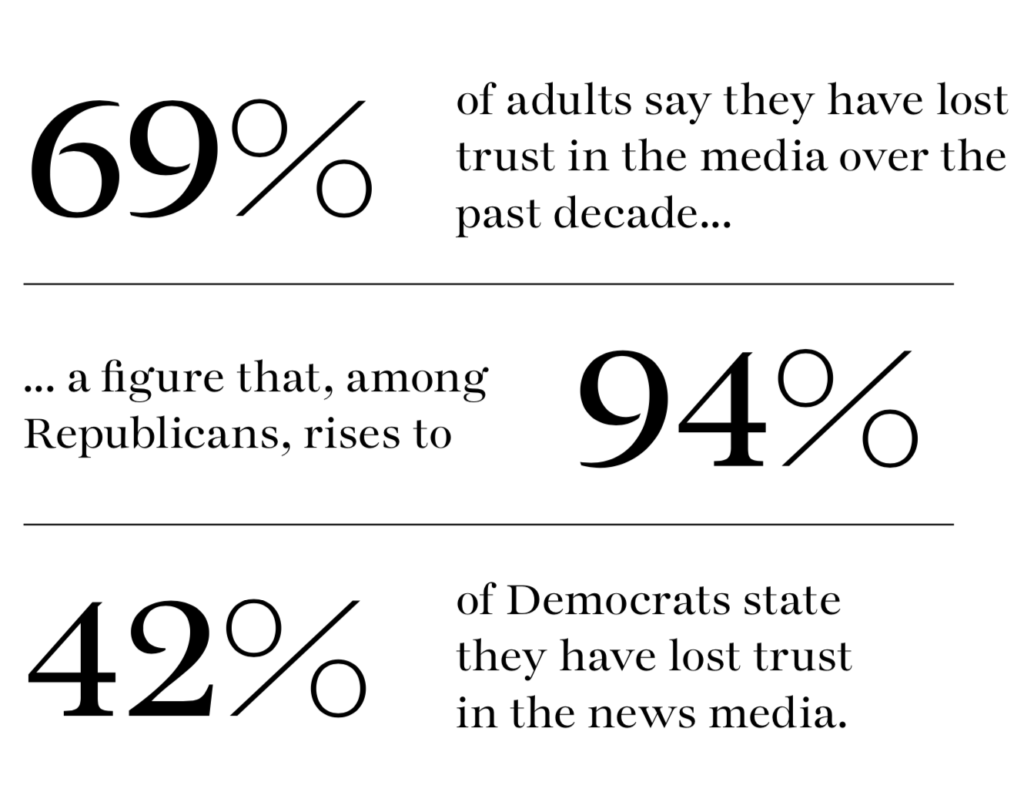

There is clearly a significant difference between sensational hyper-partisan content and slightly misleading captions that reframe an issue and affect the way someone might interpret an image. But trust in the media has plummeted. Misleading content that might previously have been viewed as harmless should be viewed differently.

A September 2018 study by the Knight Foundation and Gallup found that most Americans are losing faith in the media, and their reasons largely center on matters of accuracy or bias.

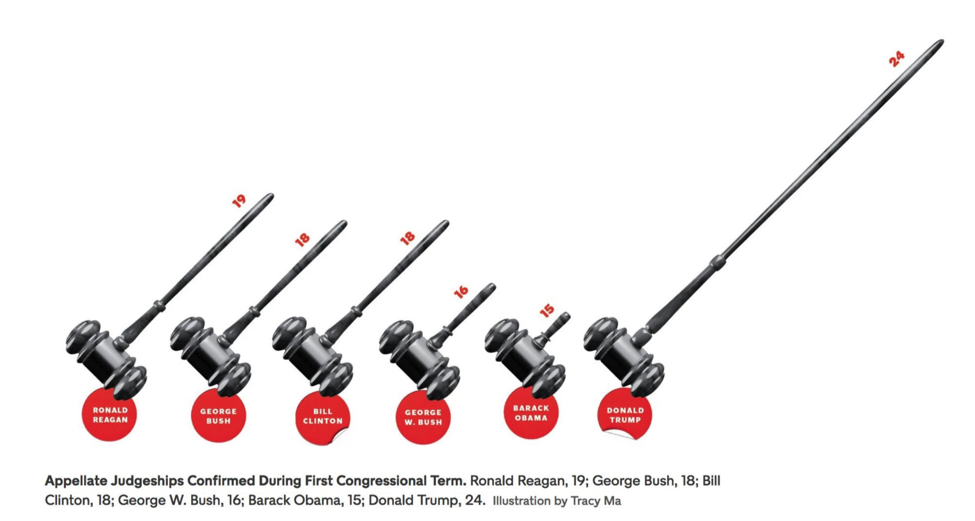

Misleading content can come in many forms, but this example from The New York Times demonstrates how visuals are also susceptible to charges of being misleading. When you look at the gavel that represents Barack Obama (15 appellate judgeships confirmed) and compare that with Donald Trump’s (24), the “scale” of the diagram is not aligned.

An illustration comparing presidential confirmations of appellate judgeships is misleading because the gavels are not drawn to scale. Trump’s gavel should be less than twice as big as Obama’s. Source: “How the Trump Administration Is Remaking the Courts,’’ The New York Times, August 22, 2018. Archived Sept 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

False context

This category is used to describe content that is genuine but has been reframed in dangerous ways. One of the most powerful examples of this technique was posted shortly after an Islamist-related terror attack on Westminster Bridge in London in 2017. A car mounted the curb and drove the length of the bridge, injuring at least 50 people and killing five, before crashing into the gates of the Houses of Parliament.

One tweet was circulated widely in the aftermath. This is a genuine image. Not fake. It was shared widely, using an Islamophobic framing with a number of hashtags including #banislam.

The woman in the photograph was interviewed afterward and explained she was traumatized, on the phone with a loved one and, out of respect, not looking at the victim. We now know that this account, Texas LoneStar, was part of a Russian disinformation campaign and has since been shut down.

An account associated with a Russian disinformation campaign implies that the Muslim woman depicted was indifferent to the victim of an attack. In reality, she was not looking at the victim out of respect. The account has been deleted but was reported in The Guardian.

An account associated with a Russian disinformation campaign implies that the Muslim woman depicted was indifferent to the victim of an attack. In reality, she was not looking at the victim out of respect. Archived on September 6, 2019.

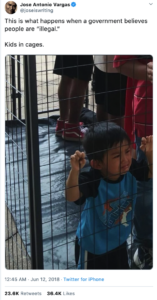

Another example that caused significant outrage was this image of a child inside a cage that circulated in the summer of 2018.

This photo depicting a child in a cage was staged as part of a protest against immigration policies. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

It received over 20,000 retweets. A similar post on Facebook received over 10,000 shares. The picture was actually staged as part of a protest two days earlier at Dallas City Hall against immigration policies — another example of a genuine image where the context got framed and warped. In this example, however, the author did not realize it was part of a protest when he shared the image. It was a case of misinformation, not disinformation.

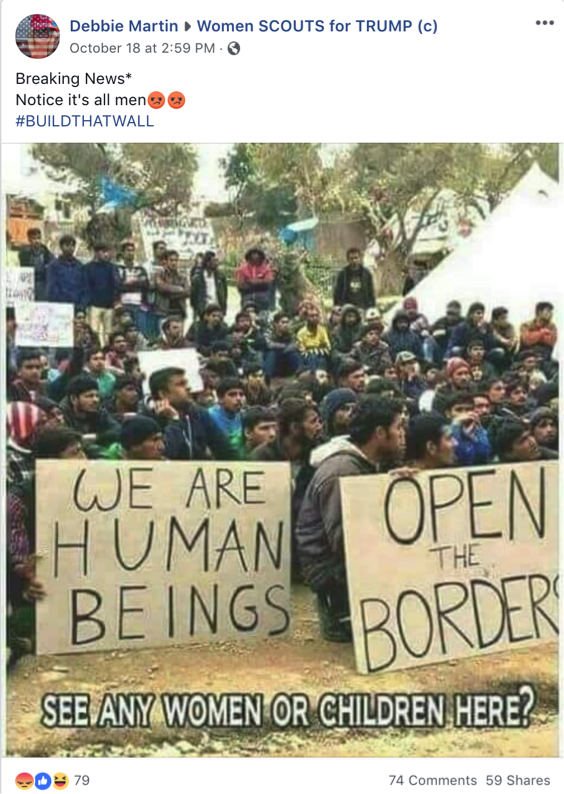

In a similar vein, during the lead-up to the US midterm election, there was a great deal of coverage around the “caravan” of immigrants traveling to the US from Central America. Genuine imagery was shared, but with misleading framing. One was this Facebook post, which was actually an image of Syrian refugees in Lesbos, Greece, from 2015.

This photo was posted in the context of the migrant “caravan” in the US, but is actually a photo of Syrian refugees in Lesbos, Greece, from 2015. The original image was shared on Twitter by the photographer. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

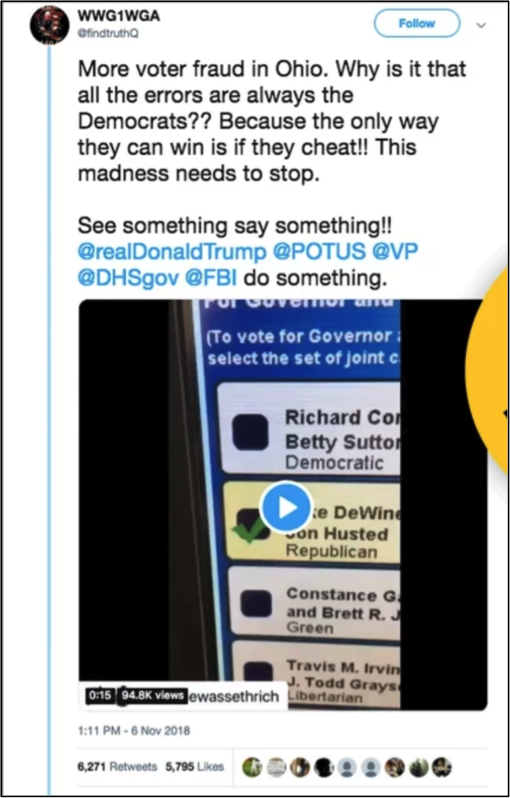

Another example of false context is this tweet that circulated on Election Day of the 2018 midterm elections. It was based on a genuine video of a broken voting machine that highlighted the wrong name when pressed. The machine was taken out of operation and the person was given the opportunity to vote on a machine that was working correctly. But this tweet, posted by someone with a username that referenced the QAnon conspiracy, used the video to push the idea that this was a more serious example of targeted voter fraud.

One user spread this image of a broken voting machine as evidence of widespread voter fraud. In reality, the machine was taken out of commission and the voter, who captured the image, was allowed to recast their vote. The tweet has been removed but was reported on by BuzzFeed. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by Jane Lytvynenko for BuzzFeed.

Imposter content

As discussed earlier, our brains are always looking for heuristics to understand things like credibility when it comes to information. Heuristics are mental shortcuts that help us make sense of the world. Seeing a brand that we already know is a very powerful heuristic. It is for this reason that we’re seeing an increase in imposter content — false or misleading content that uses well-known logos or the news from established figures or journalists.

I first came across imposter content designed to cause harm when I worked in 2014 for UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency. We were constantly battling Facebook posts where smugglers were creating pages with the UNHCR logo and posting images of beautiful yachts and telling refugees that they should “call this number to get a place on one of these boats that would take them safely across the Mediterranean.”

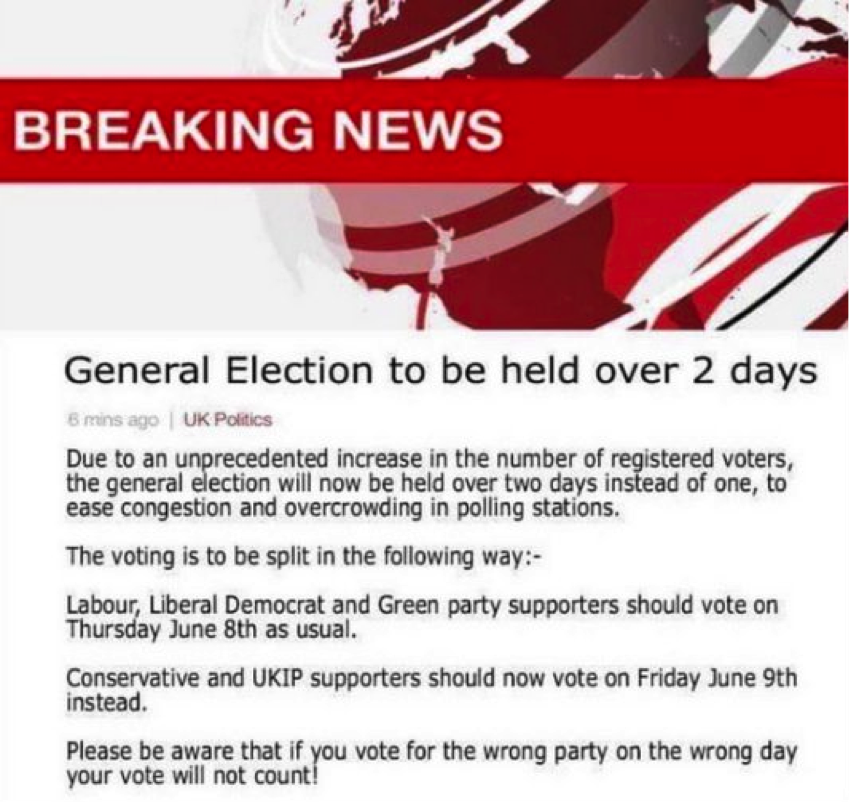

Since then, we continue to see examples of agents of disinformation using the logos of established news brands to peddle false and misleading content. Here are two examples of the BBC being used in this way. One circulated in the lead-up to the 2017 UK general election and was posted on social media. The image says that the election is over two days, and depending on your party affiliation, you need to vote on the correct day.

An imposter news site used the BBC logo to peddle misleading information about the UK election. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

The other circulated on WhatsApp in the lead-up to the 2017 Kenyan general election, prompting the BBC to put out a fact check stating that the video was not theirs, despite the clever use of BBC branding.

One video that circulated on WhatsApp used the BBC TV strap on its own content about the 2017 Kenya election. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

A more sinister example emerged during the 2016 US presidential election when NowThis was forced to issue a similar debunk because of a fabricated video that had been circulating with its logo.

An imposter video about the Clinton family posed as content produced by media company NowThis by using its branding. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

In 2017, a sophisticated imposter version of Le Soir in Belgium emerged claiming that Macron was being funded by Saudi Arabia. So sophisticated was it that all the hyperlinks in this version took you to the real Le Soir site.

An imposter site posing as Belgian newspaper Le Soir was particularly sophisticated because all of its links directed users to the real Le Soir site. The imposter site has been taken down but the original reporting on the site is available on the CrossCheck France website. Archived on September 6, 2019.

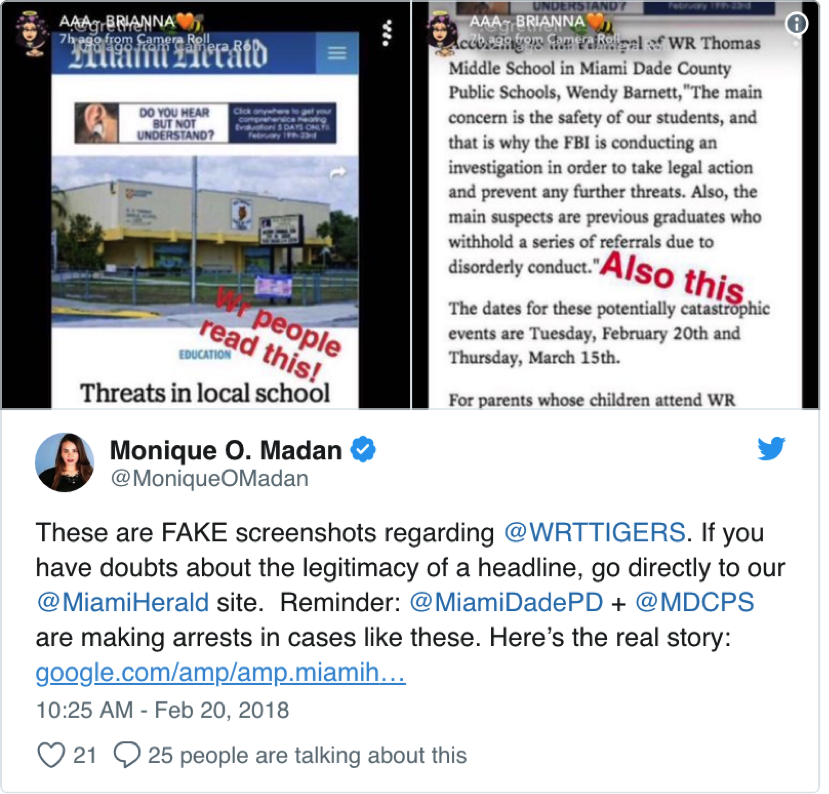

The Parkland, Florida, shooting on February 14, 2018 was the backdrop for two very worrying techniques emerging around this category of imposter content. The first involved someone taking a Miami Herald story and photoshopping in another paragraph (suggesting that another school had received threats of a similar shooting), screenshotting that and then circulating it on Snapchat.

Someone photoshopped a new paragraph into a Miami Herald story to make it appear as if additional schools were receiving threats of shootings when in reality they were not. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

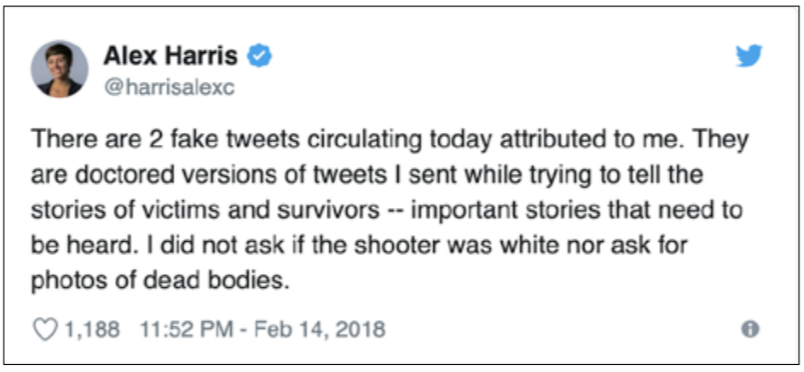

Another example also involved the Miami Herald, but this time an individual reporter, Alex Harris, was targeted. Using a fake tweet generator site that allows you to enter a user’s handle so it populates with the genuine photograph and bio, someone created two offensive tweets. They were circulated as screenshots. Anyone who went to Harris’s Twitter page would have seen that she had tweeted no such thing, but in an age where people screenshot controversial tweets before they are deleted, there was no immediate way for her to definitively prove she hadn’t posted the messages. It was a wake-up call about how reporters can be targeted in this way.

When someone photoshopped two offensive tweets and made them look as if they came from journalist Alex Harris, she alerted Twitter users on her own account, but had no way to definitively prove they weren’t true. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

Another famous example of imposter content surfaced during the lead-up to the 2016 US presidential election. Using the official Hillary Clinton logo, someone created the following image that was then used to micro-target certain communities of color in order to try to suppress the vote.

An ad that claims it was paid for by Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign makes it look as if her supporters had unfair voting advantages, but the ad is entirely fabricated. The account has since been deleted but original reporting and links are available at The Washington Post. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

Remember that the amount of information people take in on a daily basis just on their phones — emails, social media notifications and push alerts — means heuristics become even more impactful. Therefore logos, the accurate wording of disclaimers and bylines from known reporters are disproportionately impactful.

In addition to text, videos and images, we increasingly need to be aware of the power of audio to deceive. In the run-up to the Brazilian presidential election in October 2018, Jair Bolsonaro was stabbed during a campaign event. He spent the next 17 days in a hospital. During that time, an audio message circulated that purported to be Bolsonaro cursing at the nurses and stating “that the theater is over,” which led to conspiracies that his stabbing had been staged to increase sympathy — and therefore support — for the candidate. Forensic audio specialists were able to analyze the recording and confirm that the voice was not Bolsonaro’s, but instead a very authentic-sounding impersonator.

Finally, another technique that has been investigated by Snopes is the creation of sites that look and sound like professional local news sites, such as The Ohio Star or the Minnesota Sun. Republican consultants have set up a network of these, designed to look like reputable local news sites.

There are five of these sites as part of the Star News Digital Media network. They are partly funded by the Republican candidates these news sites are covering.

A site that poses as a local Ohio newspaper was actually set up by Republican consultants. Retrieved October 16, 2019. Screenshot by author.

Four websites that look like reputable local news are actually part of a network of sites set up by Republican consultants. Archived September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

Manipulated content

Manipulated media is when an aspect of genuine content is altered. This relates most often to photos or videos. Here is an example from the lead-up to the US presidential election in 2016, when two genuine images were stitched together. The location is Arizona, and the image of the people standing in line to vote came from the primary vote in March 2016. The image of the ICE officer making the arrest is a stock image that, at that time, was the first result on Google Images when searching for “ICE arrest.” The second image was cropped and layered on top of the first and disseminated widely ahead of the election.

These two images were overlaid to make it appear that ICE officers were present at a voting location. Archived on October 16, 2019.

Another example of a high-profile piece of manipulated content targeted high school student Emma González and three of her peers who survived the school shooting in Parkland, Florida. They were photographed to appear on the front cover of Teen Vogue and the magazine created a video, promoted on Twitter, of González ripping a gun target in half.

A genuine image of Parkland survivor Emma González before she tears apart a gun target on the cover of Teen Vogue. Archived on September 6, 2019.

This video was altered so it appeared González was ripping the US Constitution in half. It was shared by thousands of people, including actor Adam Baldwin and other celebrities.

A fabricated video of Parkland survivor Emma González tearing apart the US constitution. This tweet has been removed but was reported on by BuzzFeed. Archived on September 6, 2019.

Another infamous example features a video of Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, giving a speech in May 2019. The footage was slightly slowed down, and just that simple form of manipulation made Pelosi appear as if she were drunk and slurring her words.

A video of Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the US House of Representatives, was slowed down to make her appear drunk. This side-by-side video was created by The Washington Post. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

The same technique was used again in Argentina to target then-Security Minister Patricia Bullrich in the run-up to the October 2019 election there.

A video of Patricia Bullrich, Argentina’s former security minister, was also slowed down to make her appear drunk. Archived on September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

Fabricated content

Fabricated content is that which is 100 per cent false. For example, a false claim that Pope Francis had endorsed Donald Trump circulated ahead of the 2016 US presidential election, receiving a great deal of attention. The headline featured on a site called WTOE5, which peddled a number of false rumors in the lead-up to the election.

This article claims that Pope Francis endorsed Donald Trump for president, but it isn’t true. The site is no longer online but was debunked by Snopes. Archived September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

An oldie but goodie, from 2012, is the video of an eagle purportedly stealing a baby in a park. The video received over 40 million views before it was revealed that the video had been created as part of a class assignment to create content that might successfully fool viewers. The students used a computer-generated eagle; it was so believable that only a frame-by-frame analysis showed that the eagle’s wing detached from its body for a split second and its shadow later appeared out of nowhere in the background of the footage.

Another example of 100 per cent fabricated content is a video that emerged in 2014. It appeared to depict a gun battle in Syria and a boy saving a young girl. Stills from the video ran on the front cover of the New York Post. It transpired that the video was created by filmmakers, shot in Malta, and used the same film set as the Gladiator movie. They wanted to draw attention to the horrors taking place in Syria, but their actions were condemned by human rights activists who argued that this type of fabrication undermined their efforts to document real atrocities.

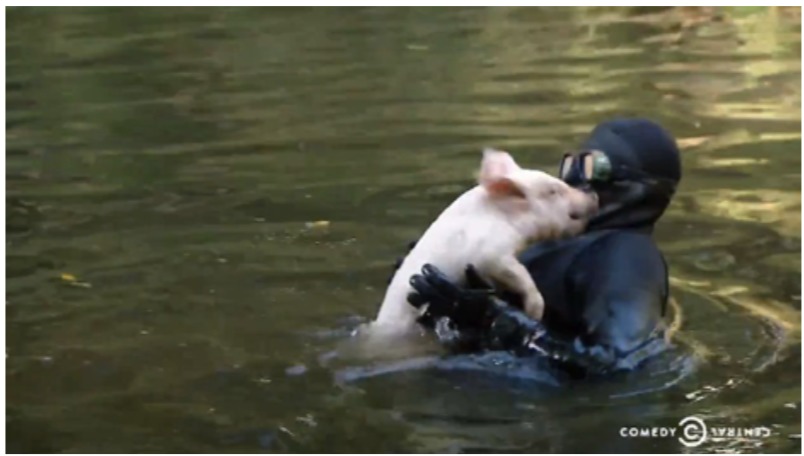

Another less tragic example stands as one of the most successful viral fabrications. Created by the Comedy Central show “Nathan for You,” it depicts a pig saving a drowning goat in a pond. The video was shared widely and featured in many “and finally” segments on television news shows. It took over six months before Comedy Central put out a video explaining the lengths it had gone to in order to create the clip. It included building a perspex “bowling alley” under the water and getting divers to guide the pig toward the goat!

Comedy Central created an elaborate underwater setup to make it look as if a pig had saved a drowning goat. People believed it was real and shared it widely. From the Comedy Central YouTube channel. Archived September 6, 2019. Screenshot by author.

As we end, it’s worth looking into the future and the next wave of fabricated content that will be powered by artificial intelligence, otherwise known as “deepfakes.” We’ve seen what will be possible via a Jordan Peele deepfake in which he created a version of former President Barack Obama.

And most recently, we saw documentarians creating a clip of Mark Zuckerberg as a test to see whether Instagram would take it down. Ironically, while Instagram said the video did not break its policies, CBS ended up flagging the content, arguing that it was imposter content because of the use of the CBS logo (see Chapter 4).

This fabricated clip of Mark Zuckerberg was not taken down by Facebook, but CBS flagged the content for using its logo. Archived on September 6, 2019.

Conclusion

Information disorder is complex. Some of it could be described as low-level information pollution — clickbait headlines, sloppy captions or satire that fools — but some of it is sophisticated and deeply deceptive.

In order to understand, explain and tackle these challenges, the language we use matters. Terminology and definitions matter.

As this guide has demonstrated, there are many examples of the different ways content can be used to frame, hoax and manipulate. Rather than seeing it all as one, breaking these techniques down can help your newsroom and give your audience a better understanding of the challenges we now face.

This HTML version of this Essential Guide is the most up-to-date.

Click here to download a PDF version of this guide – last updated October 2019

About the author

Claire Wardle currently leads the strategic direction and research for First Draft. In 2017 she co-authored the seminal report Information Disorder: An Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy for the Council of Europe. Prior to that she was a Fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, Research Director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and head of social media for the United Nations Refugee Agency. She was also the project lead for the BBC Academy in 2009, where she designed a comprehensive training program for social media verification for BBC News that was rolled out across the organization. She holds a PhD in Communication from the University of Pennsylvania.

Claire Wardle currently leads the strategic direction and research for First Draft. In 2017 she co-authored the seminal report Information Disorder: An Interdisciplinary Framework for Research and Policy for the Council of Europe. Prior to that she was a Fellow at the Shorenstein Center on Media, Politics and Public Policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School, Research Director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and head of social media for the United Nations Refugee Agency. She was also the project lead for the BBC Academy in 2009, where she designed a comprehensive training program for social media verification for BBC News that was rolled out across the organization. She holds a PhD in Communication from the University of Pennsylvania.