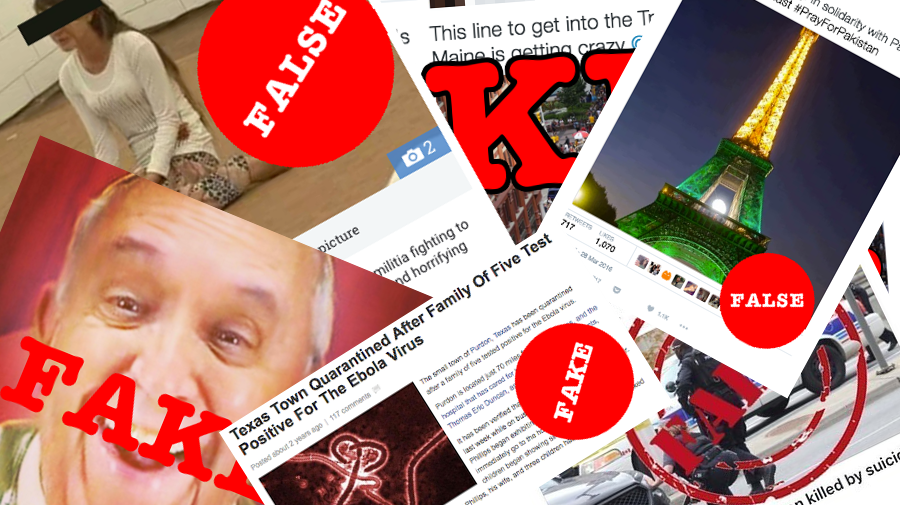

For some it is a prank, akin to a crank call for the digital age. For others, it’s a narcissistic effort to rack up likes and followers. Others see political opportunity and want to hijack people’s attention for their own political or commercial gain.

I’ve written before about those who originate misinformation and spread fake images during crises and disasters. But once the misinformation is out there, why do people share it? And how can understanding this question help us combat rumors and foster more trustworthy coverage and reporting during breaking news?

People want to help

People have never felt as close to breaking news as they do today. It shows up daily in our social media feeds, through graphic pictures and autoplay videos, unfiltered and raw. A series of tweets or a Facebook live video can bring us to the scene of a shooting, a bomb explosion, an earthquake. The result can be, as one author writes, a “burgeoning sense of helplessness.”

In the face of a tragedy unfolding in front of you a lot of people want to help. They want to tell their followers what is going on, to pass along important information, share dramatic photos that help add context to the chaos. Sometime these posts are even accompanied by warnings, safety advice, and specific calls out to friends and followers who might be affected. Matt Stempeck has studied how people mobilize online to support each other through “peer aid” in times of crisis.

Be careful of fake “victim” tweets around the #manhattan explosion story in Chelsea NYC. All these are fakes: pic.twitter.com/VKjJ3Cdgfm

— Alastair Reid (@ajreid) September 18, 2016

Scammers know this and take advantage of people’s desire to help on social media through likes and shares. However, a rush to share without verifying the legitimacy of the information can hurt much more than it can help.

People want to make sense of the world

In his research on the spread of misinformation, Craig Silverman cites Nicholas DiFonzo and Prashant Bordia’s definition of a rumor as “unverified and instrumentally relevant information statements in circulation that arise in contexts of ambiguity, danger, or potential threat and that function to help people make sense and manage risk.”

During breaking news, more is unknown than known. Rumors arise in that paucity of information as we grasp for meaning and understanding. “Rumors emerge to help us fill in gaps of knowledge and information,” Silverman writes. “They’re also something of a coping mechanism, a release valve, in situations of danger and ambiguity.”

Rumors are just stories, and stories are the engine through which we make sense of the world. Often, people are quick to share rumors during breaking news because the rumors give them something to hold on to, confirm some story in their minds, or resonate with their view of the world.

People want to feel part of the shared experience

On September 11, 2001 I watched the twin towers fall live on TV, all alone, surrounded by boxes. My wife and I had just moved into a new apartment, in a city where we didn’t know anyone. She was at her first day of work while I was home unpacking. As the enormity of what had happened sunk in I raced down the street to a pay phone and tried to call everyone I knew in New York, but didn’t get through to anyone.

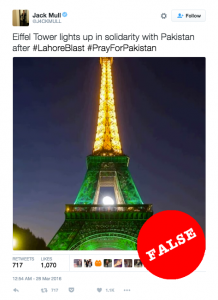

In the face of the uncertainty, sadness and fear that crisis and disaster inspire, it is no surprise that people seek out connection online. They gather in digital crowds around hashtags and livestreams. They long to be a part of this shared moment, to see their own pain reflected back at them. In those moments sharing can feel like an act of empathy.

In the face of the uncertainty, sadness and fear that crisis and disaster inspire, it is no surprise that people seek out connection online. They gather in digital crowds around hashtags and livestreams. They long to be a part of this shared moment, to see their own pain reflected back at them. In those moments sharing can feel like an act of empathy.

We see this with the rush to share images of memorials, like the often fake or recycled pictures of landmarks lit up to honor the dead. And we see it in the spread of images and hashtags of solidarity. In these cases, when misinformation spreads it is often shared more for the message it sends and the connection it creates. In that case, for the person sharing, it doesn’t need to be true, it just needs to feel true.

Emotional Networks versus Information Networks

It is easy to demonize those who share rumors and misinformation during breaking news, but in reality the impulse to share is driven by a complex web of motivations and emotions. In the wake of the Paris attacks in November of 2015, Kenyatta Cheese wrote on Twitter: “The spread of misinformation in a social network is a feature, not a bug.” When I asked him to clarify he said, “Maybe what people want to share isn’t the information but the emotional trigger. Maybe in a social context it’s no longer an information network but an emotional network.” This idea stuck with me, and the examples I highlight above bear that out.

During breaking news, the networks that connect us become as much about information as emotion, and that emotion drives sharing in ways that complicate the search for truth in the moment of crisis or disaster. On his blog, Cheese wrote, “When people share information that is wrong, they do it because they’re more interested in the emotion the information evokes. When news organizations do it, it’s bad journalism.”

The problem with the idea of social networks operating as both emotional and information networks is that what people share (emotion) and what people want to find (facts) are often in contradiction. And in moments of crisis, when first responders, government and the press are turning to social media to get critical, trustworthy and at times life saving information out, this contradiction can become dangerous.