If you’re a user of a major social network, chances are you’ve been friended, followed or mentioned by a suspicious-looking account at some point. They probably tried to sell you something or get you to click a link, and you were probably able to spot the fake and avoid the trap. It’s not tough to avoid eggs on Twitter spitting out nonsense or bikini-clad strangers who add you out of the blue on Facebook.

While you have likely seen these kind of accounts before, what you may not know is the scale of the social media fakes: Facebook reportedly has around 170 million known fake accounts, and Twitter may have as many as 20 million fakes. Whole industries exist around creating and selling such accounts.

Even more interesting is that fake accounts aren’t just the domain of scammers and advertisers. Increasingly, governments and state actors are actively investing in online sockpuppets and spam bots to influence public opinion, stifle dissent, and spread misinformation.

In researching the topic, we found reports of social network manipulation in some form by governments all around the world, including the USA, Russia, China, Mexico, Syria, Egypt, Bahrain, Israel, and Saudi Arabia. This is by no means an exhaustive list (if readers have more suggestions, please add links as comments) and the extent and strategy of manipulation varies greatly.

To get an idea of what is possible, let’s look at two very different examples, observed in Mexico and Russia.

Mexico: El Ataque de los “Peñabots”

In Mexico, people have been using hashtags on Twitter to call attention to important political issues. Hashtags like #YaMeCanse and #SobrinaEBN quickly gather momentum and “trend” on Twitter, serving both as a high-profile space to draw attention to public figures’ misdeeds and as a space for social organization.

Not long after the hashtags trend, however, something strange happens:

Thousands of users flood the hashtag posting nonsense content or, in other cases, content that is suspiciously similar.

These are hashtags that have come under attack. While it’s difficult to say with certainty who or what is behind the attack, the intent and effect is clear: spamming hashtags en masse triggers Twitter’s anti-spam measures, dropping the hashtag from Trending Topics and making it very difficult for people to discover the hashtag or meaningfully participate in the conversation.

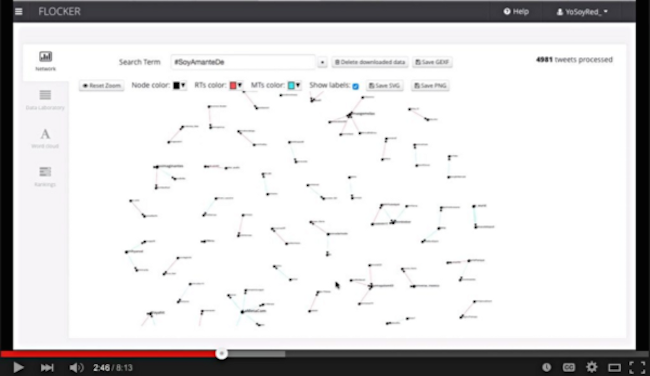

At the same time as real hashtags sink under the weight of spambots, other hashtags appear, pushing the critical hashtags further from public view. Researchers Alberto Escorcia and Erin Gallagher (who have both written extensively on this and other techniques observed on Mexican social networks) note that these new hashtags are fake, and are flooded with bot participants. Network analysis shows the clear difference between real hashtags (in this case #Acapulco) and fake hashtags (in this case #SoyAmanteDe, which appeared shortly after #Acapulco was attacked by bots).

A real hashtag (#Acapulco) — notice the number of connections between nodes. Images from Revolution-News.com

A bot hashtag (#SoyAmanteDe) — notice the lack of networked activity

These fake accounts that flood hashtags have become known as “Peñabots” — a popular reference that connects these spambot armies to Mexican president Enrique Peña-Nieto.

Russia: Social-savvy sockpuppets

Over the past 12 months or so, there have been numerous reports written about sockpuppets and bot armies with seemingly strong links to the Russian government.

From Lawrence Alexander’s excellent analysis and tracking of Russian botnets at Global Voices to Adrian Chen’s in-depth look at the activities of one so-called “troll factory” in St. Petersburg for the New York Times, it’s clear that there is much to be studied.

An interesting counterpoint to the bot-driven hashtag attacks observed in Mexico (as well as in Russia and elsewhere) emerges from Chen’s work: elaborate misinformation campaigns that require significant human time and effort.

Chen tells of the panic and confusion in the Louisiana town of St. Mary Parish when, on September 11, 2014, a local official receives a text message informing him of an explosion at one of the town’s chemical processing plants, Columbian Chemicals, and the leaking of toxic fumes. On Twitter, word of the explosion was already spreading:

“A powerful explosion heard from miles away happened at a chemical plant in Centerville, Louisiana #ColumbianChemicals,” a man named Jon Merritt tweeted. The #ColumbianChemicals hashtag was full of eyewitness accounts of the horror in Centerville. @AnnRussela shared an image of flames engulfing the plant. @Ksarah12 posted a video of surveillance footage from a local gas station, capturing the flash of the explosion. Others shared a video in which thick black smoke rose in the distance. Dozens of journalists, media outlets and politicians, from Louisiana to New York City, found their Twitter accounts inundated with messages about the disaster.”

In addition to screenshots of the news on CNN — reporting a possible attack by ISIS — shaky video emerged of an Arabic-language TV channel broadcasting an apparent claim of responsibility.

Spot the dodgy accent and, if you look closely, the disjointed Arabic on the screen: a poorly rendered fake.

“The Columbian Chemicals hoax was not some simple prank by a bored sadist,” writes Chen. “It was a highly coordinated disinformation campaign, involving dozens of fake accounts that posted hundreds of tweets for hours, targeting a list of figures precisely chosen to generate maximum attention.

“The perpetrators didn’t just doctor screenshots from CNN; they also created fully functional clones of the websites of Louisiana TV stations and newspapers. The YouTube video of the man watching TV had been tailor-made for the project. A Wikipedia page was even created for the Columbian Chemicals disaster, which cited the fake YouTube video.

“As the virtual assault unfolded, it was complemented by text messages to actual residents in St. Mary Parish. It must have taken a team of programmers and content producers to pull off.”

Sockpuppets, censorship and source verification

Beyond understanding how networks can be manipulated in the ways presented in the examples, it’s important to think about the wider impact of such interventions and what we can do to challenge them.

Reading through the example of network manipulation in the Mexican context, answering the question “why” is simple: hashtags are attacked to limit the public’s ability to hold public figures to account. This is censorship. Other bot hashtags are created to smear individuals and movements. This is disinformation.

Asking the same question of the Russian-context example, however, is less straightforward. Why go to such great lengths to create, coordinate and promote this kind of fake news? Ethan Zuckerman, Director of the Center for Civic Media at MIT, frames these manipulations as “a new chapter in an ongoing inforwar,” the latest in a long line of efforts by states to produce news that reflects their viewpoint and strategic priorities.

“Who benefits from doubt?” he writes. “Ask instead who benefits from stasis… It’s expensive to persuade someone to believe something that isn’t true. Persuading someone that nothing is true, that every ‘fact’ represents a hidden agenda, is a far more efficient way to paralyze citizens and keep them from acting.”

Elaborate disinformation campaigns, then, seek to undermine the credibility of social networks themselves — the very spaces where criticism of a government or public figure happens become the target of suspicion and doubt.

It’s worth noting that this skeptical mindset is something that groups working in verification have advocated for a long time, and it is perhaps the nurturing of this mindset and digital media literacy that holds the key to derailing disinformation campaigns. Any of the Checkdesk partner network or First Draft Coalition would quickly have found flaws in the Columbian Chemicals charade, through analysing the sources of the disinformation and problematic content.

In the coming weeks and months, we’ll be conducting ongoing research into this topic area at Meedan, looking specifically at what tools and techniques can be used to conduct source-level verification and tell the bots from the nots and the sockpuppets from the genuine accounts.

This is an edited version of an article which first appeared on the Meedan Medium publication, republished with permission.