To have a year begin with blood in the streets, beamed around the world, and bookended with the living nightmare that beset Paris’s 10th arrondissement last Friday is a horror no city should have to endure. Too many do.

French news organisations, as can be expected, went in to overdrive to find the information their audiences demanded, meeting them on social media, where all the questions were asked, and debunking rumours as best they could. But the rise in power of social networks, where every user is a publisher in their own right, has led to a weakening of traditional news media.

Most news outlets make the merest splash in the newsfeeds of the wider population. For the more engaged readers it might be a stream. But news organisations are no longer the raging rivers to the ocean of public information they once were.

“We shouldn’t be naive with social networks,” said Samuel Laurent, editor ofLe Monde’s Decodeurs channel for debunks, fact checks, explainers and data journalism. “There is bullshit happening in social networks. On Sunday, people wanted to gather in Paris, they went to the Place de République and there there was a huge panic caused by some noise, a car breaking too fast or something.

“If you were on Twitter you could see it helped share the panic, saying there are gunshots. It was amplifying the panic. It’s important to understand that sharing isn’t virtual any more. It is real. It can have a real effect, in real life.”

Hundreds of people flee the Place de la République in Paris after false alarm caused panic https://t.co/N2jN48kTCD https://t.co/ehsBUhojeU

— Sky News (@SkyNews) November 15, 2015

The nature of the tragedy in Paris is not new, even if the scale was. To call the Charlie Hebdo massacre a trial run for 13/11, as it is already becoming known, may seem crude but among the many lessons learned was a renewed cynicism in online sources.

After all the rumours, hoaxes and lies surrounding January’s attacks — widely seen as an assault on journalism, press freedom and free speech — many French journalists were invited to schools. They explained the process of journalism to children and teenagers: the foundations of media literacy, the questioning of sources and checking of information.

“That was the turning point,” said Julien Pain, editor in chief of France 24’s Observers, which operates in French, English, Arabic and Farsi to debunk rumours and hoaxes. “Before that people were just checking political speech… Then after Charlie Hebdo and all the fake images that came out, and the impact they had, everybody realised we had to be working on that.”

Pain started Observers back in 2007 when he persuaded senior figures at broadcaster France24 that social media and UGC would be the next frontier in news, a year after the channel launched. The Twitter account for the French language version, @Observateurs, now stands at 142,000 followers, while Le Monde’s @Decodeurs, started by Laurent to fact check France’s 2011 election, has a following of nearly 44,000.

Along with Liberation’s @LibeDesintox and BuzzFeed France’s new @Verifie channel, French media are taking the debunks to the hoaxers where they are, meeting them head to head on social networks.

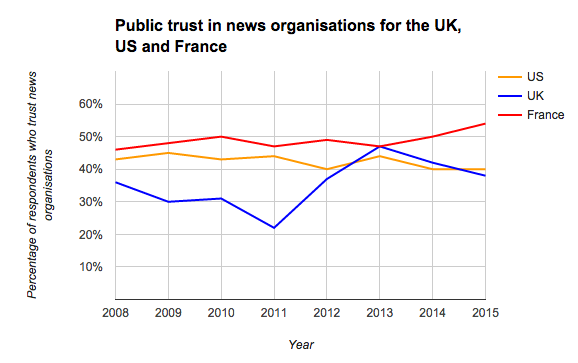

In the US, overall trust in the media has dropped to a historic low of 40 per cent, according to a recent Gallup Poll, a figure that slips further to 38 per cent in the UK.

UK trust in news took a heavy hit as a result of the phone-hacking scandal. Sources: Gallup (US), Edelman (UK), TNS(France). Explore an interactive version of this graph here

Partisan alternative news sites, which don’t have the same editorial standards, are becoming the outlets of choice for those disillusioned by the status quo and the establishment is largely not stepping in to stop the rot.

“There’s a real need to educate people about how to inform themselves and how not to be fooled,” said Laurent, “there’s a huge demand and it’s interesting for news organisations to be able to do that. We are expected to do this.

“[Audiences] don’t know when they see a website if it’s serious or not. You have lots and lots of websites that pretend to be serious and in France, maybe the same in the UK, we have Twitter accounts who are pretending to be news agencies but are just one person behind a screen watching TV and saying ‘this is breaking news’.

“These accounts are followed by tens of thousands of people and they are dangerous in times of crisis like this because they say bullshit all the time and people share it. I think we have to make the audience understand that all information is not the same quality and not all information is good information.”

“We have to be more active because a rumour can spread widely long before journalists notice it,” agreed Adrien Sénécat, who runs BuzzFeed France’s Verifie account, via email. “So we don’t just have to wait for it: we have tolook for it and answer it precisely, while being careful not to help spread the rumour, but to answer it.”

The chaos of the attacks and their aftermath were a hellish situation to report from, and Sénécat has been working overtime since to set the record straight.

Le mec fait croire à une prophétie des attentats, mais c’est un fake. L’original est ici : https://t.co/bOw4rLZJAu pic.twitter.com/dPLinAtYg5

— Adrien Sénécat (@AdrienSnk) November 14, 2015

The concern for many English-language news outlets is that the demand for debunks just isn’t there among audiences.

Verified information about a story like Paris — with global interest and global repercussions — will always be popular but First Draft member Craig Silverman identified a lack of incentive for debunks in his report ‘Lies, Damn Lies and Viral Content’ in February. Some organisations prefer being first to harness the traffic a sensational story from social media can bring, he wrote, over wasting resources on disproving something clickable.

The result is a graveyard for debunks with many quality news outlets not touching false news or hoaxes, while the pictures, videos, stories and claims circulating on the social web are left to travel unimpeded. In such a landscape it’s no surprise trust in journalism is crashing.

But, when done right, “debunking is now a click machine”, said Pain.

“The articles you put out about debunking and fake information, they get thousands and thousands of hits,” he said. “As a journalist you know these articles work really well because people are interested in this kind of information.”

In the eight years since the launch of Observers Pain has honed the technique of communicating a debunk effectively without letting the original rumour spread further, and said the key is in identifying the audience interest in a debunk and being clear in its presentation.

“We have a big logo we put at the top of the image,” said Pain, “which is ‘debunked’ in English, ‘intox’ in French and the same in Arabic and Farsi.

“It’s a big logo that goes all across the image to make it very clear the image is fake. Then, even if people don’t circulate our article and only the image, it will be on the image. That’s one of the tricks.”

An image debunked by Observers claiming to show the Eagles of Death Metal concert at the Bataclan theatre, the site of one of the attacks in Paris. The photo was actually taken in Dublin.

@Verifie takes a similar approach, said Sénécat, as “mostly a distributed project, meaning it lives on the social web where it makes the most sense, because that’s also where a lot of the rumors or fake info live.

“So the essence of Verifie is to be able to answer the question ‘is it true of false’ the right way, whether in a tweet, an image or a post.”

Pain believes videos are a more effective way to reach younger readers as well, using the established techniques for popular videos on social media to grab people’s attention in their newsfeed.

And as with any story, the key to finding an audience for debunks is to find the human interest, covering topics people are passionate about where the audience already exists.

At Observers, that means finding “what’s really dangerous, really shared and what could have an effect on people’s mind,” said Pain, going beyond just the nature of the hoax or misinformation but also asking why it is being spread.

“What’s interesting with this kind of debunk story is you always find an audience. If you’re debunking propaganda by a Muslim website then you get all the far right coming to you and spreading the information.

“And then you put out something saying ‘oh the far right is bullshitting about this’ and you have the Islamic websites coming to you and suddenly circulating your news. They always find a large audience.

“People are really interested in being explained why the information is true and I find it fascinating. They want to know how you check, they don’t just want you to say ‘it’s checked’. They want to know how you know it and prove it, which is good.”

Pain’s guide to verifying false information was published days before the attacks and has been shared widely, as was Decodeurs’ ‘7 tips to thwart rumours’, published the day after the attacks.

“We just wrote a little thing saying ‘good tips not to be fooled by hoaxes’,” said Laurent. “Just simple things saying if you have something from an anonymous source maybe it’s not relevant, you can’t believe it because you don’t know the people, you don’t know where it’s from so don’t share it. Basic stuff. This little article was shared [almost] 20,000 times.”

Audiences largely understand the internet is full of rumour and misinformation. But, when turning to traditional outlets in the UK and US for guidance, too often find them indifferent at best and complicit at worst.

The situation would be immeasurably more tragic if a similar wake up call was the only thing to spur them into action.