This study was carried out by the author, María Celeste Wagner (University of Pennsylvania, USA), Eugenia Mitchelstein (Universidad de San Andrés, Argentina), and Pablo J. Boczkowski (Northwestern University, USA), acting as external consultant.

Do people believe the information they receive through messaging apps? Does the identity of the sender influence the credibility of that information? When do people feel more inclined to share content they have received? In the midst of the ongoing pandemic, when rampant misinformation has exploded on social media and closed messaging services, these questions are more pertinent than ever.

Evidence from a December 2019 online experiment in Argentina, where respondents read and then responded to the quality of news around vaccines and climate change, could contribute to answering some of these questions.

Contrary to narratives underscoring the persuasive power of some misinformation, evidence from our experiment suggests that Argentine audiences — at least — are good at differentiating facts from falsehoods and do not blindly accept information from personal contacts.

In other words, we observed that many people were highly critical when reading news about various scientific topics. This could be partly related to a generalized skepticism in Argentina and distrust of information that is thought to be sent by personal contacts.

Top findings:

- Contrary to widely held beliefs, participants were more distrustful of news they believed had been sent by a personal contact than of news where they lacked information about the sender.

- Participants were more distrustful of stories about vaccines and climate change which turned out to be false than they were of factually true stories on the same subject.

- It is unclear how effective fact-checking labels are in correcting for misinformation.

The study

In recent years, there has been growing scholarly and journalistic attention given to issues relating to mis- and disinformation. A large part of this work has focused on analyzing how false content flows online, mostly during political or electoral processes. It has also centered on how political disinformation could change opinions and, eventually, voting preferences. Although valuable, most of this work has focused primarily on the Global North, and on two platforms in particular — Facebook and Twitter.

We sought to counter this dominant trend by examining how people from a country in the Global South (in this case Argentina) consume misinformation on health and the environment on messaging apps.

To do this we conducted an online survey with 1,066 participants in December 2019. The survey was representative of the Argentine population in terms of socioeconomic status, age and gender.

During the online survey, participants were shown news stories about vaccines and global warming and asked to imagine a situation in which they had received these news stories on WhatsApp either from a relative, a colleague or a friend. Half of our participants read four real news stories about the effectiveness of flu and measles vaccines, the roles of human activity in climate change and of the role of carbon dioxide in global warming.

Factually correct stories ran with the following headlines:

- Vacunarse anualmente previene la gripe y sus complicaciones (Annual vaccination prevents the flu and its complications)

- Si bien el dióxido de carbono compone una parte pequeña de la atmósfera es una de las causas del calentamiento global (Although carbon dioxide makes up a small part of the atmosphere, it is one of the causes of global warming)

- El calentamiento global de los últimos 70 años se debe en gran medida a la actividad humana (Global warming over the past 70 years is largely due to human activity)

- El continente americano ya no es más una región libre de sarampión (The American continent is no longer a measles-free region)

The other half of the participants read false news that had been circulating online in Argentina about these same topics. In order to make everything as comparable as possible, we only changed minimal aspects of the false and real news stories.

False stories ran with the following headlines:

- Vacunarse anualmente no previene la gripe y sus complicaciones (Annual vaccination does not prevent the flu and its complications)

- El dióxido de carbono compone una parte muy pequeña de la atmósfera y por ende no puede ser una de las causas del calentamiento global (Carbon dioxide makes up a very small part of the atmosphere and therefore cannot be one of the causes of global warming)

- El calentamiento global de los últimos 70 años se debe en gran medida a causas naturales (Global warming of the past 70 years is largely due to natural causes)

- El continente americano sigue siendo una región libre de sarampión (The American continent remains a measles-free region)

The assignment of these two factors — the person who was sharing the news, and the veracity of the news — was random. All participants judged the veracity and credibility of each news story they had read and expressed how willing they would be to share each news item.

At the end of the study, those participants exposed to false stories were notified that they had been shown false content and the factually correct stories were then shared with them.

A forthcoming study from academics in Argentina reveals some interesting findings on how people consume information on WhatsApp. Source: Pixabay

Credibility, trust, and sharing

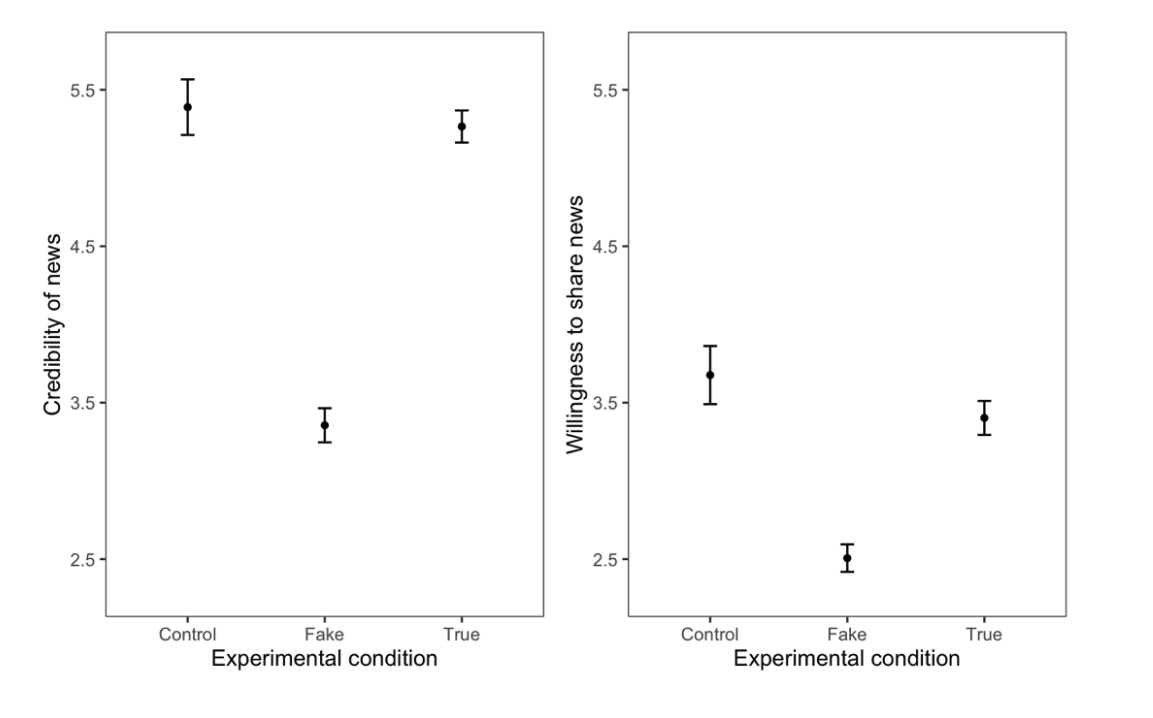

We found that people who had read false news stories about vaccines and global warming before being told they were false assessed them as less credible and less truthful than those who read real news stories about those same topics.

In other words, participants distrusted stories with misinformation about vaccines and climate change more than those comparable stories with true information. They also expressed less willingness to share stories with misinformation in comparison to the news stories that were true. These findings were especially positive given the current concern around the spread of Covid-related falsehoods and rumors.

Our study also showed that those reading stories containing misinformation were significantly less likely to believe that others would trust those stories than those reading accurate news. This suggests that participants extended their critical stance to others. In addition, people showed a general level of distrust towards their contacts. For example, having information about the person who forwarded a story significantly lowered both the credibility of the message and the receiver’s willingness to share it, compared to a control group that lacked information about the source. In other words, people were more distrustful of news they believed had been sent by a personal contact than from news where they lacked information about the sender.

Credibility of news and willingness to share news by experimental condition (true, false and control news). Note: Both credibility and willingness to share were measured on a scale from 1 to 7. The control group read the true news, but instead of being told that someone was messaging them the information, they were told to imagine they were finding this news in a newspaper. 95% CI. We used ANOVA tests for comparisons of means. For comparisons of means across different levels of one factor, Tukey tests were used. All reported findings are statistically significant at a p-value<0.05.

We found no significant gender differences. Receiving news from either a female or male relative, friend or colleague did not result in any significant differences among our measured outcomes of credibility and sharing. Furthermore, telling participants any information about a specific source that sent them the message — a relative, a colleague or a friend — increased their later perceptions that other friends, colleagues or relatives would get upset if the participant were to forward them the news. Overall this suggests that participants do not seem to blindly trust their personal contacts. On the contrary, they are distrustful of what people might send them regardless of the relation.

Fact checking

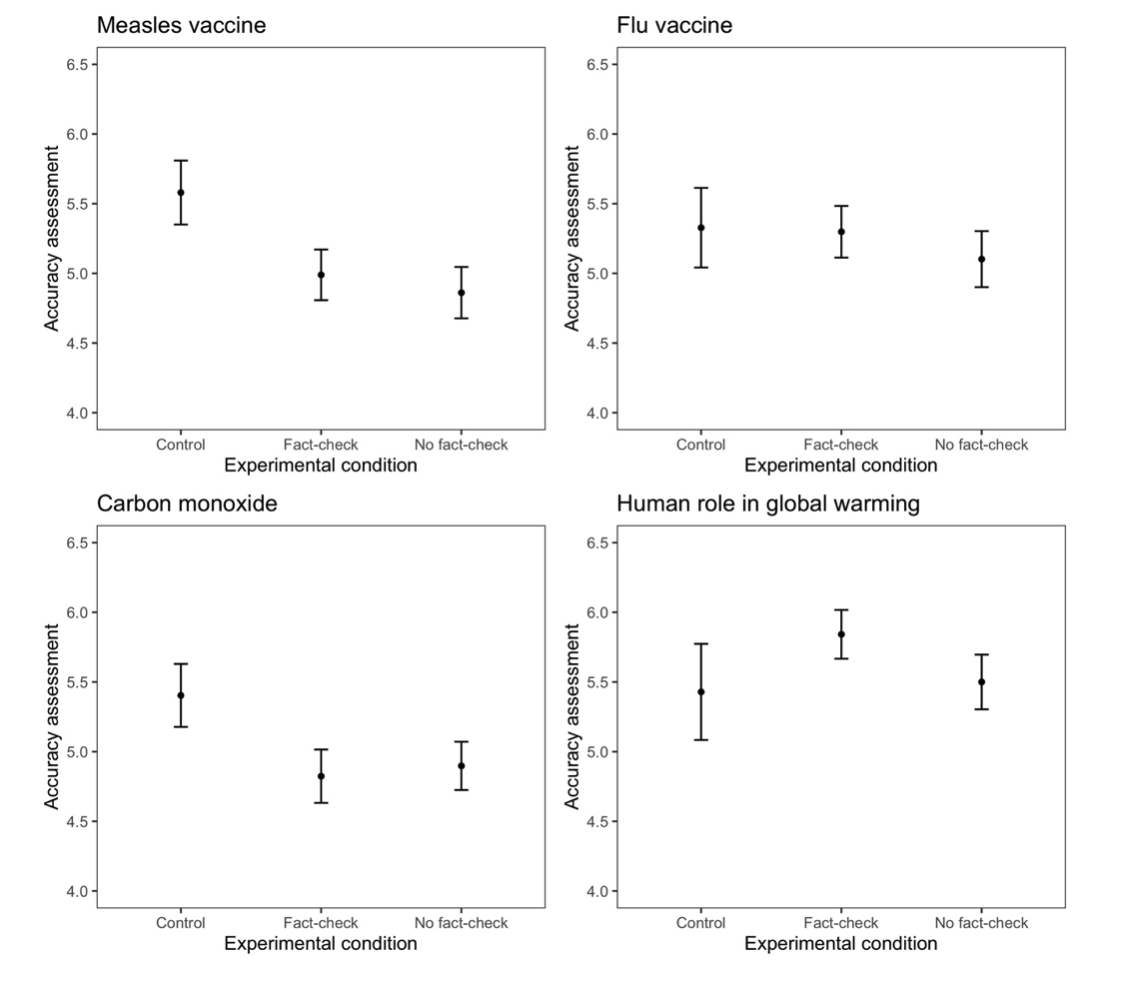

We also tested the effect of fact-checking labels on evaluating the accuracy of information. After reading false content on global warming and vaccines, half of the participants who had been exposed to and had evaluated these false stories were told that fact checkers had determined the content to be false. At the end of the survey, after a series of distracting measures, all participants were asked to assess the veracity of a number of statements, some of which related to the vaccine and global warming topics they had read about earlier.

We found evidence suggesting that reading false news does have negative effects on participants’ ability to accurately assess information in those stories. Those who read factually correct news about measles vaccines and the role of carbon monoxide in global warming were able to more accurately assess the validity of statements related to those topics than those who had been exposed to false stories. This suggests that reading false news seems to have a negative effect on how people assess information. We did not find significant effects of this in the other two stories: those related to the flu vaccine and the human role in global warming.

Accuracy assessment of statements related to the four scientific topics covered in the news by experimental condition (control, fact-checked, not fact-checked news). Note: All accuracy assessments were measured on a scale from 1 to 7. Higher values mean more accuracy. Accuracy assessments of information about these four topics were measured at the end of the study, after participants read true or false (with fact-checking labels or not) information. The control group read true news about these topics, but instead of being told that someone was messaging them the information, they were told to imagine they were finding this news in a newspaper. Both the “fact-check” and “no fact-check” groups read false news. 95% CI. We used ANOVA tests for comparisons of means. For comparisons of means across different levels of one factor, Tukey tests were used. All reported findings are statistically significant at a p-value<0.05.

We also found discouraging results around the efficiency of fact-checking labels. A fact-checking label would be efficient if someone reading a false story is then told the story they read was deemed false by fact checkers and they then adjusted their position over time by remembering that the information they had read was inaccurate.

However, we found this to be the case only for the news story about the impact of humans on global warming. Those participants who read a fact-checking label were later able to more accurately assess information related to that issue than those people who had been exposed to a false story without the fact-checking label.

When it came to stories about measles vaccines, flu vaccines and carbon monoxide, we found no significant difference on later accuracy assessment between those participants who read a story labeled false and those who read a story without a label. These findings might be due to features that are specific to our study design. It could also be the case that fact-checking labels which do not correct misinformation with accurate information are less reliable, or that receiving a fact-checking label confuses participants in a way that makes it harder to cognitively correct for misinformation later on.

Conclusions

In summary, the Argentine public rated false content on vaccines and the environment as significantly less credible, and was less likely to share false information than true information. Including data on the identity of the sender — friend, family member, colleague — decreased both the credibility and willingness to share the stories.

Despite narratives on the destabilizing power of misinformation on social media during democratic political processes and global events, such as the current Covid-19 pandemic, our findings contribute to the current debate by showing that in a Global South context, even when false news seems to have some negative impact in subsequent opinion-formation, Argentines are good at identifying false information and are wary of the information their personal contacts share with them on messaging apps.

This research was independently designed by the research team, but was supported by a grant from WhatsApp.