As they start their careers, doctors swear to uphold the Hippocratic Oath. If people tackling misinformation were to establish an equivalent oath, we should make sure to borrow one of the original’s phrases: “Prevention is preferable to cure.”

As with medicine, so with misinformation: It is better to prevent misinformation from spreading at all than to try to debunk it once it’s spread.

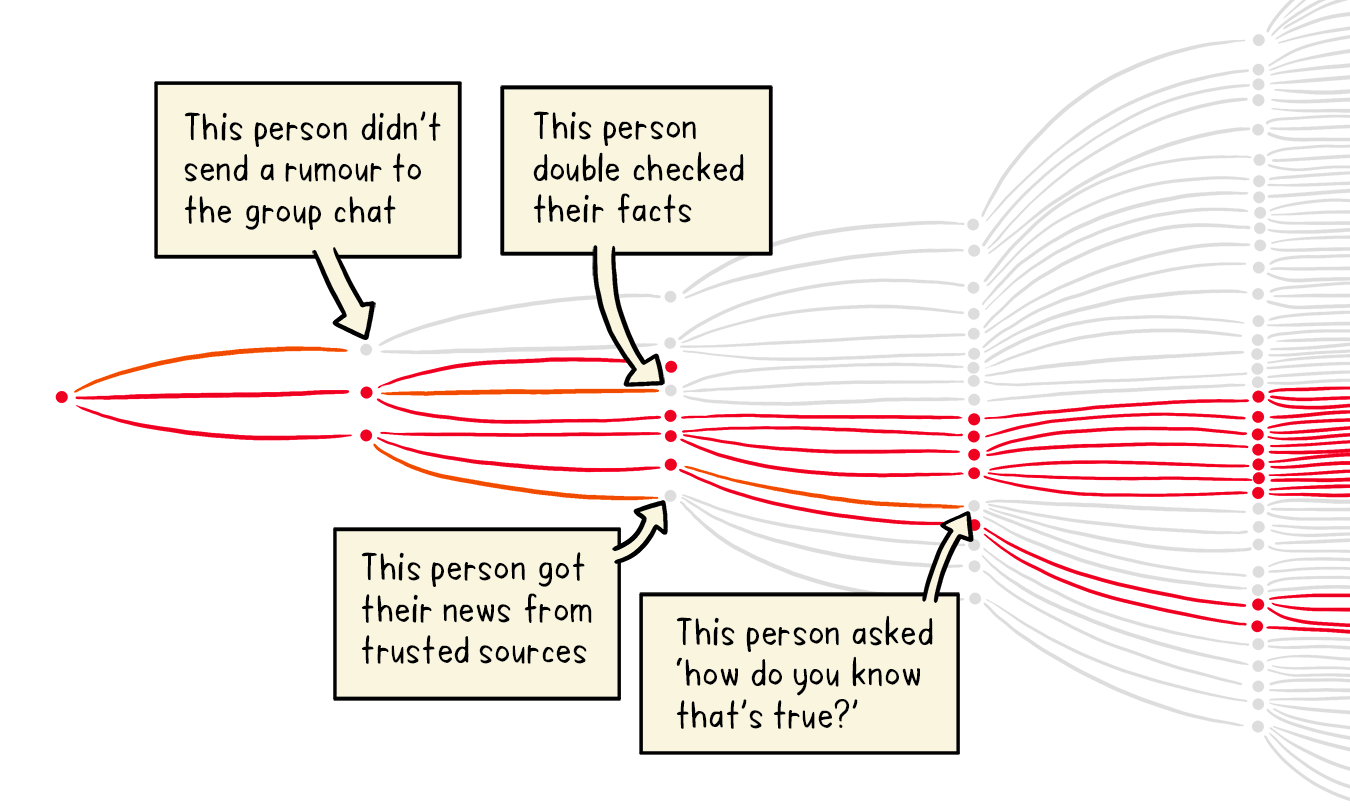

Here’s why. Debunks don’t reach as many people as misinformation, and they don’t spread nearly as quickly. If they do reach us, they generally struggle to erase the misinformation from our debates or our brains. Even when we’ve been told that the misinformation is false, research suggests it continues to influence our thinking.

So it helps to take a page from medicine: Prevention, not cure, may be a more effective way to combat misinformation.

Understanding how prebunks work (and how they don’t) is essential for reporters, fact checkers, policy makers and platforms.

The basics

The idea of inoculating people against false or misleading information is simple. If you show people examples of misinformation, they will be better equipped to spot it and question it. Much like vaccines train your immune response against a virus, knowing more about misinformation can help you dismiss it when you see it.

Inoculating people can be achieved through a number of tools or approaches, such as First Draft’s text message course that texts you one lesson per day, games such as “Go Viral!” that put you in the shoes of a bad actor, or simply the ability to track down and share an article that prebunks key claims and techniques.

And research shows that these methods work. For example, five minutes of playing the game “Go Viral!” can reduce susceptibility to misinformation for up to three months.

The goal with prebunking. Source: WHO

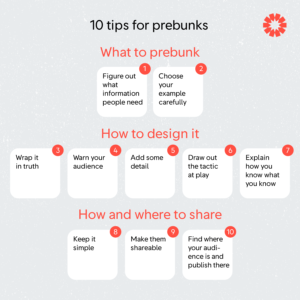

Prebunking: how to do it

The most accessible inoculation technique is prebunking — the process of debunking lies, tactics or sources before they strike. They can be quick and cheap for reporters, fact checkers, governments and others to make.

A good prebunk addresses people’s concerns, speaks to their lived experience and compels them to share that knowledge. Prebunks are empowering: The whole point is about building trust with your audience instead of simply correcting facts.

There are three main types of prebunks:

- fact-based: correcting a specific false claim or narrative

- logic-based: explaining tactics used to manipulate

- source-based: pointing out bad sources of information

Research has shown that the logic-based approach has far-reaching benefits. If you teach people to recognize tactics, they can spot them more often than individual claims.

John Cook, a research fellow at the Climate Change Communication Research Hub at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, has been exploring inoculation for years. He told First Draft that the ideal prebunk will combine “fact and logic so people can understand the facts but also be able to spot attempts to distort the facts.”

What to prebunk

1. Figure out what information people need

Anticipate your audience’s questions. Don’t assume that your questions are the same as your audience’s. Use tools such as Google Trends to figure out trending questions or issues, check in with community figures and think about creating a space where people can submit their questions.

What is it that people find confusing? What pre-existing narratives might bad actors exploit? Are there any events coming up, including elections or health campaigns, that people might need more information about? How can you help people identify these tactics and narratives so that they are less likely to fall for them?

2. Choose your example carefully

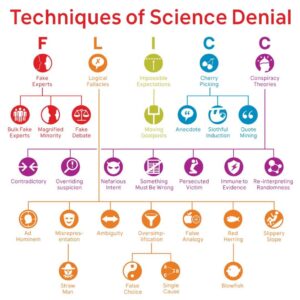

Examples of the disinformation tactics that a prebunk could warn about and explain. Source: skepticalscience.com

Some rumors crop up again and again, and will reliably resurface. Focus on them.

- Focus on a claim when there are likely to be key vulnerabilities, such as right before an election. A false claim might be that the date of an election has been changed.

- Focus on tactics if you want to build more generalized resilience to disinformation. A tactic might be the use of fake “experts” to bolster a lie, or the use of emotional language to manipulate you.

Cook has found this while researching inoculation against climate change misinformation. He showed participants examples of tactics used in tobacco misinformation. Afterward, they were all able to spot climate change misinformation regardless of their political beliefs.

“This tells us that regardless of where you sit on the political spectrum, nobody likes being misled,” says Cook.

How to design it

3. Wrap it in truth

Prioritize the truth. That means either leading with the facts or a very clear warning of how information is being manipulated. The “truth sandwich” — a factual wrapper — works for both prebunks and debunks.

Extract from the Vaccine Misinformation Guide showing the “factual wrapper” strategy for prebunks and debunks.

4. Warn your audience

Before you repeat the myth, warn your audience. Remind your audience that people are trying to manipulate us and why. This puts people’s guard up, increasing their mental resistance to misinformation. This could simply be a warning that some people will try to mislead others about the scientific consensus on climate change for political reasons, or a reminder that some individuals profit from selling fake cures.

“It is important to provide cues or warnings before you mention the myth, because you want to put people cognitively on guard when they are reading the myth,” explains Cook.

5. Add some detail

You don’t want to overwhelm your audience, but try to pack in a few reasons why something is false. This helps to increase belief, and arms people with counterarguments they can use to debunk the claim when they encounter it.

6. Draw out the tactic at play

If you’re correcting a false claim, remind your audience that this tactic is not exclusive to this example. Use false claims as teaching examples to help your audience recognize the tactics or strategies being used for manipulation. Sometimes an example from an issue that is less political with your audience can be just as effective as a teaching tool.

7. Explain how you know what you know (and what we don’t know yet)

Explaining how you know what you know helps to build trust. This helps people resolve the conflict between fact and myth and gives your audience the tools to reject the claim in the future. Explaining what we don’t know yet helps warn your audience that the facts might change as things develop.

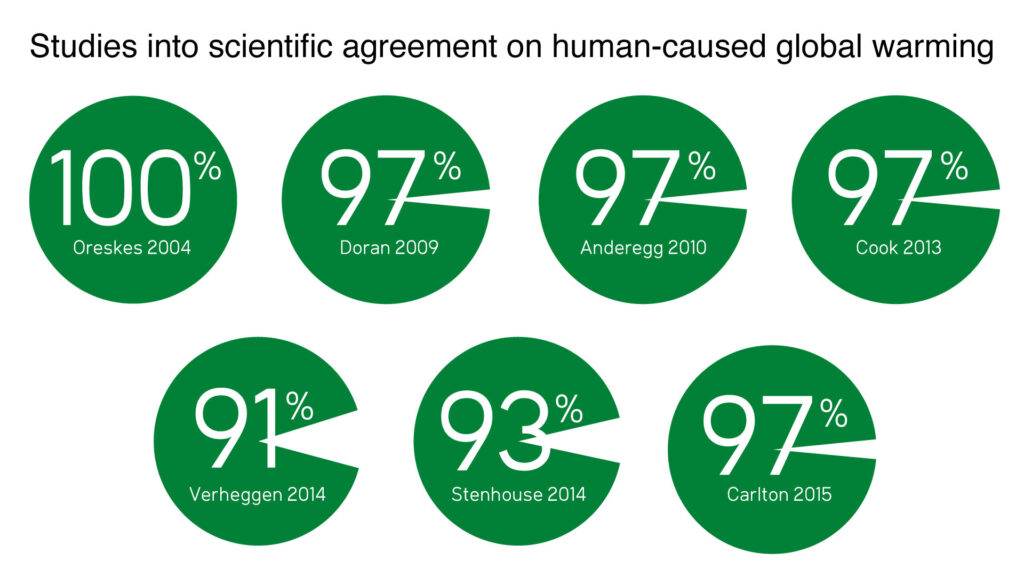

Expert consensus results on the question of human-caused global warming among the previous studies published by the co-authors of Cook et al. (2016). Illustration: John Cook.

One way to do this is to focus on consensus: Remind people of what experts agree on and why. This is common when talking about climate change, where there is almost unanimous agreement among scientists, and can help to target the disinformation tactic of false debate.

How and where to share

8. Keep it simple

Break it down into the simplest version of the idea so it’s easier to remember and spot afterward. Infographics, especially those that build on ideas that are already widely shared, are a great way to prebunk. Five debunks that each contain an idea are better than one debunk that contains five ideas but is confusing. Don’t get lost in the weeds.

9. Make them shareable

Whether it’s online or offline, in the end we’re talking about people. People spread misinformation because they’re searching for answers, and they share what they find. If you want your prebunk to go far, design it so it’s shareable. Think about the strategies that bad actors use to spread disinformation: The idea is to use those same time-proven techniques, but for good. Design your prebunks with mobile phones in mind. For many people, mobile phones are their sole access to the internet and much of their lives happen on closed messaging apps, including WhatsApp or Facebook Messenger, which don’t use up as much data.

10. Find where your audience is and publish there

Successful prebunks will join and be integrated in online spaces and platforms where your audience is already spending time. Think of it like a party: If you’re in a room alone providing good information while everybody else is outside in the garden having a drink, your prebunk won’t go far. Use social listening and monitoring tools to figure out the digital spaces where “the party” is happening and join in.

As with parties, you’ve got to read the room before you jump into the conversation. Think about the culture of the specific online space or platform you have identified. What does engaging content look like? What are the trends or styles that people use to communicate? How can you use those in a way that effectively communicates the information you want people to have?

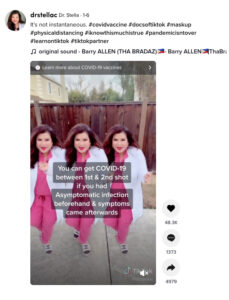

Dr. Stellac regularly publishes prebunks on TikTok using dance trends to provide information that anticipates people’s questions.

Want to dive deeper?

The theory and evidence around inoculation have been pioneered by researchers such as Cook, Dr. Sander van der Linden and many others. New research is being published all the time, and it is worth keeping track of if you’re implementing an inoculation-based campaign, game or project.

Here are some readings to get you started:

- Can you outsmart a troll (by thinking like one)?

- Countering Misinformation and Fake News Through Inoculation and Prebunking

- Can “Inoculation” Build Broad-Based Resistance to Misinformation?

If all this sounds a bit boring, try out one of these games so you can inoculate yourself:

- Bad News

- GO VIRAL! | Stop Covid-19 misinformation spreading

- Cranky Uncle

- Troll Factory

- Harmony Square

- Fake It To Make It

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.