The challenge of monitoring, understanding, defining and responding to mis- and disinformation is exacerbated during election campaigns. This report outlines tactics used by agents of disinformation to undermine elections as observed by First Draft’s global monitoring since 2015. This is placed within a brief overview of the characteristics and vulnerabilities that bear consideration during elections in the Australian context. Campaign tactics have also furthered the spread of falsehoods and mis- and disinformation in Australia. This creates additional challenges (for which there are emerging solutions) when debunking political misperceptions that people may initially label as ‘misinformation’.

This report outlines why word choices matter. Consideration must be given ahead of an election to the level of understanding audiences and politicians alike have of definitions. Regardless of political leaning, they must be able to consider whether a claim that something is ‘misinformation’ could actually be political bias or misunderstanding of the definitions. As the Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation noted, concepts and definitions “mean different things to different people and can become politically charged when they are used by people to attack others who hold different opinions on value-laden political issues on which reasonable people may disagree.” The code also noted “understanding and effects of these concepts varies amongst individuals and is also under-researched.” First Draft recommends more research from an Australian perspective in this field.

The crucial role journalists play in countering political falsehoods and slowing down mis- and disinformation is explained. We encourage research, training and outreach that focus on this role and help prepare audiences for misinformation so they are better equipped to spot it and question it.This must be an ongoing pursuit, so that quality information is within easy reach of the public. This report also challenges politicians to consider their campaign responsibilities with regard to the role they may play in the spread of misleading information, and aims to help policy makers and legislators make informed decisions about supporting the information ecosystem.

Introduction

An election is an easy target (and opportunity) for the creation of misleading information. It can take many forms — memes, articles, audio messages, videos, screenshots and even comments on social media posts. Generally speaking, First Draft refers to misleading content as either misinformation or disinformation; the difference between the two is intent:

- Disinformation is when people deliberately spread false information to make money, influence politics or cause harm.

- Misinformation is when people do not realize they are sharing false information. It is important to understand that most people share misleading content out of genuine concern and desire to protect others.

In reality, it is rarely so neat. The lines between mis- and disinformation can blur, overlap and be repurposed. Often when disinformation is shared it turns into misinformation. Take, for example, false Covid-19 “remedies,” many of which have caused real-world harm. Conversely, something that starts as misinformation can be picked up by disinformation agents with an agenda. For example, a journalist misreporting the cause of an Australian bushfire season as an arson wave which is then picked up by conspiracy theorists with a climate denial agenda. A third category, called “malinformation,” exists when the information is true, but is shared maliciously, (e.g., leaked emails or revenge porn). First Draft co-founder Claire Wardle collectively referred to the different types and interplay of misleading content as information disorder.

Wardle noted that the “weaponization of context” — where genuine content has been warped and reframed — is a particularly effective tool for agents of disinformation and “far more successful in terms of persuading and engaging people.”

As noted above, definitions are complex and can mean different things to different people. First Draft has updated nuances and explanations as tactics in Information Disorder evolve. For example, socio-psychological factors are behind why people share misinformation, as has been particularly evident during the pandemic. As First Draft reported, online, people perform their identities. They want to feel connected to their ‘‘tribe,” be it members of the same political party, parents who don’t vaccinate their children, activists concerned about climate change, or those who are a certain religion, race or ethnic group.

The political ideology of an audience member can influence their perceptions of credibility and hence what they may consider to be ‘misinformation’. In what is known as the worldview backfire effect, a person rejects a correction because it is incompatible with their worldview, and can cause them to double-down on their views. If information is coming from a source they suspect disagrees with their beliefs, they may say it is ‘misinformation’ rather than realizing it is their opinion. Research suggests political ideology can also influence trust in the media. For example, in the case of anti-lockdown protests where much of the narrative was anti-government, mainstream media were also portrayed as untrustworthy for being the ‘source’ reporting on government messaging. In Australia, by May of 2020 protesters began to take their ‘offline’ disinformation comments into the real world in Melbourne. The seemingly disparate groups of anti-vaccination and anti-government contrarians adopted rhetoric from international conspiracy theories. This included false information about Bill Gates and the government trying to microchip citizens, as well as 5G mis – and disinformation and other health misinformation. These narratives continued as different protests evolved throughout the pandemic. More recently this worldview backfire effect was evident among the Convoy to Canberra protests.

Australian context and political salience

The events of 2019 and 2020 were a watershed moment where ordinary Australians gained a heightened awareness of mis- and disinformation in their own country. This included higher exposure to and engagement with various forms of mis- and disinformation during the coronavirus pandemic, the summer of bushfires and the 2019 federal election. Many examples from these events show Australia’s current and future vulnerabilities to mis- and disinformation.

These issues were quickly politicized in Australia. Those at risk of being targeted by agents of disinformation included government agencies, e.g., through fabricated social media pages that contained anti-Asian sentiment. Racist narratives from the pandemic added to the challenges for diaspora communities; these narratives sprang from a 2019 federal election that consisted of extreme right-wing, white nationalist online disinformation campaigns and hyperpartisan campaigns pushing anti-immigration agendas.

Meanwhile, Chinese communities were targeted by misleading campaign material in the form of signs that resembled those used by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC), which supervises and organizes elections. The federal court found the signs, written in Chinese on how to vote, were misleading and deceptive. But the AEC also found there was “no real chance” the signs could have affected the results and ruled out referring the Liberal party’s former Victorian state director to the high court over his role in authorizing the signs. This was despite admissions that the signs were intended to look like the AEC’s material. Chinese communities was also targeted in “how to vote” scare campaigns in hidden chat rooms.

Australian politicians use negative campaigns and “attack ads” to target opposing candidates and policies. The 2019 vote also saw debunked information used as part of an online political scare campaign about inheritance tax. This “zombie rumour” about death taxes was repeated by mainstream politicians from the ruling Liberal party and hyperpartisan groups such as the nationalist party One Nation. They took a kernel of truth and adapted it for their purposes. Research by academics Andrea Carson, Andrew Gibbons and Justin B. Phillips used a content analysis of 100,000 media articles and 8 million Facebook posts to track the claim, and found “a number of actors circulating and co-opting the death tax story for political purposes.”

As First Draft reported at the time: Labor requested Facebook remove the posts, warning in a letter that there “seems to be an orchestrated message forwarding campaign about the issue.” Facebook Australia told First Draft that the original post was fact checked by third-party fact checkers and was rated as “False.” “Based on this rating, people who shared the post were notified. … As a result, the original post and thousands of similar posts received reduced distribution in News Feed,” a Facebook Australia spokesperson said.

The “death tax” claim tactics echoed Labor’s 2016 negative campaign, which included emotional television ads that suggested the Liberal-National Party coalition planned to privatize the nation’s public health care service, Medicare. Academic researchers Andrea Carson, Aaron J. Martin and Shaun Ratcliff found the so-called “Mediscare” campaign “significantly raised the issue salience of healthcare with voters, and it had an impact on vote choice, particularly in marginal electorates.” The researchers found the campaign slowed a decline in support for the Labor party “that was evident prior to the commencement of the negative campaign” and “this negative campaign was effective in shaping the 2016 electoral outcome,” which resulted in a narrow victory for the coalition, led by Malcolm Turnbull.

Sticking power and political persuasions

Research shows, perhaps unsurprisingly, that when it comes to fact checks on political content, people “take their cues from their preferred candidate” especially when the information challenges the political identity to which they feel they belong. That is not to say that fact checks don’t work; rather, the problem is in how they are delivered, and how regularly people stumble upon or are reminded of the fact-check content. As American political scientist Brendan Nyhan explained, “with the exception of a few high-profile controversies, people rarely receive ongoing exposure to fact checks or news reports that debunk false claims.”

As a solution, Nyhan suggests the communication style of scientists, journalists and educators should “minimize false claims and partisan and ideological cues in discussion of factual disputes” and instead highlight “corrective information that is hard for people to avoid or deny.” For example, “opinion” TV shows or columns that invite guests with alternative viewpoints for the sake of “balance,” such as climate denial, do not follow the proven science, and allow for a false equivalence in discussions.

Research has borne out the importance of getting reporting that fully explains context and events, rather than just “he said/she said,” in front of people. More continuous targeting with quality information is also essential. As Carson et al noted, “when journalists adjudicate claims (i.e., refute false claims within stories rather than simply providing competing “he said/she said” accounts) it can be beneficial to both the audience and media source.”

As noted below, a patchwork of laws and a laissez-faire approach to political advertising have resulted in a lack of accountability in political campaigns, and the spread of falsehoods, mis- and disinformation. The research above shows the need to include debunks throughout stories, as it sets challenges for journalists attempting to cover politics particularly stuck in the daily “horse race” and “he said/she said” reporting cycle.

The oldest, and newest, tricks in the election playbook

First Draft has covered elections around the world since 2015 — from France to the UK, EU, Brazil, Nigeria, US, New Zealand and Australia. From this, we have come across numerous election tropes and online election interference tracks. An awareness of these helps prepare the public for similar narratives, and journalists to counter them as they happen. Election interference around the globe observed by First Draft has taken three main tracks. This is supported by academic research by Allison Berke, executive director of the Stanford Cyber Initiative, beginning with “the spread of disinformation intended to discredit political candidates and the political process, discourage and confuse voters from participating in elections, and influence the online discussion of political topics”.

1. Disinformation intended to discredit candidates and confuse the public:

The above example from First Draft’s CrossCheck Nigeria shows how journalists countered misleading claims designed to confuse voters about the fingerprint they could use in Nigeria’s February 2019 general election.

This is a genuine image (above) from Brazil of an intact ballot box on the back of a truck. It was circulated widely in WhatsApp along with a false rumor that ballots had been “pre-stamped” with a vote for Fernando Haddad in the 2018 election (it had NOT been tampered with).

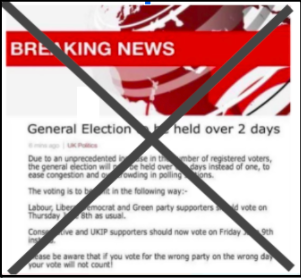

An example (above) of a fabricated BBC news site used to spread false information during the 2017 UK general election.

2. The second track covers the use of information operations to disrupt election infrastructure, including:

- changing vote records and tallies;

- interfering with the operation of voting machines;

- impeding communications between precincts and election operations centers;

- providing disinformation directing voters to the wrong polling place or suggesting long wait times;

- incorrect ID requirements, or “closures” of precincts that do not exist.

3. This is followed by the undermining of public confidence in electoral processes after an election has taken place.

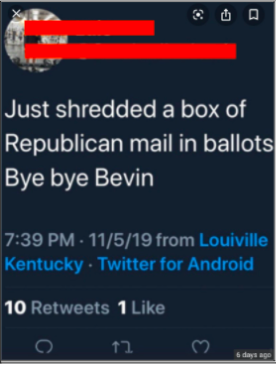

An example (above) of the false and fabricated claims perpetuated the US stolen-election myth throughout social media.

Many of these tracks to undermine results were most notable in US elections and the January 6 US Capitol riot. The 2020 US election was mired in stolen-election myths online. These included false claims that the use of Sharpie pens had invalidated ballots, and other discredited claims about voting systems, “deleted databases” and “missing boxes.”

While this may seem a world away from Australia, First Draft monitoring at the end of 2021 had already picked up attempts to introduce similar false narratives here. For example, in October 2021, former Senator Rod Culleton tweeted that the “AEC proposes to acquire ‘Dominion Voting Systems’ machines / The AEC is proposing the use of the same Dominion Voting Systems machines to count votes that are being used in America. You know the voting machines where the integrity of these machines is being questioned.” The Australian Election Commission replied that Dominion was “not a provider and won’t be one for the next federal election / electronic voting seems a long way off, let alone a provider for such a thing / Regardless of what was proven or not in US, Aus system so different that comparisons are not useful.”

An unproven claim that has appeared several times in the comment sections of social media monitored by First Draft questioned the provision of pencils in polling booths, and said votes marked in pencil could be tampered with. The AEC explained that pens are accepted alongside the pencils provided in polling stations: “The provision of pencils in polling booths is a requirement of section 206 of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918. There is, however, nothing to prevent an elector from marking his or her ballot paper with a pen if they so wish. The AEC has found from experience that pencils are the most reliable implements for marking ballot papers. Pencils are practical because they don’t run out and the polling staff check and sharpen pencils as necessary throughout election day. Pencils can be stored between elections and they work better in tropical areas.”

There are also comments that contain inaccurate information about voting methods, such as “you should vote from your computer using your medicare card as id.” However, the AEC website shows that online voting is not an option.

Embracing the fringe to gain status

First Draft has reported on how fringe candidates use misinformation to gain outsized online influence, a reach they wouldn’t otherwise have. Their misleading, attention-grabbing campaign videos and posts are viewed by thousands, their campaign messages are plastered on roadside billboards, in letter box drops and even in traditional media advertisements. When they are banned or “deplatformed” from mainstream social media and technology platforms, they simply encourage their followers to move with them to unregulated or anonymous sites, where they regroup. Researchers for The Conversation note the concerns this raises, as “complete online anonymity is associated with increased harmful behavior online.”

Australia has also seen several candidates criticized for using misinformation to gain status online, often tapping into conspiracy theory communities and challenging the existence of Covid-19 or questioning the efficacy of vaccines.The Covid-19 pandemic has provided fringe candidates additional space, attention and audience. They are able to tap into the concerns and anti-establishment sentiment shared by anti-maskers, anti-lockdown supporters and anti-vaccine activists. These voices have turned these messages from the pandemic into political campaigns.

Careful reporting about these candidates is required in order to help reduce information disorder; however, journalists must be aware that covering these stories can have the undesired effect of amplifying misinformation. Therefore, responsible reporting (rather than simply giving media attention and catchy headlines to often-outrageous claims) is key. First Draft provides resources on how to approach reporting on these topics.

Deepfakes, shallowfakes and the power of satire

Hours after a June 2021 leadership spill saw Barnaby Joyce voted in as the new leader of Australia’s National Party and deputy prime minister, an old video in which he appeared drunk was gaining traction on social media. Fortunately, the video was debunked just as quickly as a “shallowfake.”

The 39-second video purported to show Joyce’s slurred rant against the government, but it had been deliberately slowed down to make him sound drunk. Extracting keyframes from the video and conducting a reverse image search, First Draft found the original video. It was posted to Joyce’s verified Twitter account in December 2019 and has been viewed more than 800,000 times since.

The doctored video, meanwhile, had been viewed more than 2,000 times within an hour before it was deleted. First Draft contacted the uploader and was told that the clip was meant to be a work of satire, but having noticed people’s confusion, the uploader would take it down.

As Wardle said, “Satire is used strategically to bypass fact checkers and to distribute rumors and conspiracies, knowing that any pushback can be dismissed by stating that it was never meant to be taken seriously.” Even when it is purely a work of art, satire can be a powerful tool that has potential to do harm, because not everyone in the community might realize it’s meant to be a joke. The more it gets reshared, the more people lose the connection to the original post and fail to understand it as satire. On the other hand, satire can also be an effective means to educate the public on politics – as research into popular comedy shows such as the Daily Show has found. Research into the effect and the ability of the public to understand what is mis- and disinformation via Australian satirical sites is warranted.

In the disinformation field, a video that has had its speed or volume altered to paint someone in a negative light is considered a “shallowfake.” As opposed to “deepfakes” — fake visual or audio materials created by artificial intelligence — “shallowfakes” are products of relatively simple methods, such as tampering with the audio or cutting out several frames, often with malicious intent, as Sam Gregory, program director of human rights nonprofit WITNESS, noted.

Back in 2019, First Draft was already formulating best practices about reporting on shallowfakes and other types of disinformation to avoid further amplification and confusion. While deepfakes like the fabricated “Obama video” were much feared, shallowfakes such as the series of distorted videos of US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi can be more destructive, as they are easy and fast to create.

The visual nature of a deepfake is problematic, because people are less critical of visual misinformation. Compared to memes, misinformation in deepfakes can be even more damaging, as videos can be more believable and subversive. Our advice for those who may be targets of AI-enabled disinformation, particularly during an election — and for those reporting on it — is to have a library of videos ready to show the original where possible.

A patchwork of accountability

The Australian public’s ability to identify mis- and disinformation is further compromised during an election season because of a lack of “catch-all federal laws to prevent lies” in political advertising. Other laws and regulations, such as consumer laws, focus on false or misleading behavior in the promotion of goods and services and do not extend to political ads. The Australian Communications and Media Authority, which regulates broadcasting and telecommunications, has oversight of rules such as the amount of airtime allowed for political advertising, but this does not cover the content of these ads. Australia’s self-regulatory system for commercial advertising includes a complaints process administered by Ad Standards. As ABC FactCheck reported, while Ad Standards hears complaints about misleading ads, these are “only where they target children or relate to food and beverages or the environment.”

The Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation, which aims to reduce the risk of online misinformation causing harm to Australians, was finalized and adopted during the pandemic by Adobe, Apple, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Redbubble, TikTok and Twitter. The code acknowledges the primacy of Australian laws, including for electoral advertising, but otherwise largely exempts “political advertising or content authorized by a political party.” This is perhaps no surprise given the lack of accountability from the patchwork of laws that do not directly target political advertising. First Draft research from monitoring the Facebook Ad Library during the 2020 New Zealand election and referendums was a useful exercise in cataloging the way politicians and activists make use of this space to propagate their agenda and publish their “attack ads.”

The Discussion Paper released with The Australian Code of Practice on Disinformation and Misinformation noted the need in a democracy for any rules or laws in relation to online content to “avoid imposing unnecessary restraints on freedom of speech and expression.” The Discussion Paper made note of further complexities: “People may also simply disagree with opposing political statements and attempt (incorrectly) to label this as misinformation. It is important also to recognize that information is never ‘perfect’ and that factual assertions are sometimes difficult to verify.” To this, First Draft would add that some facts take time, and pressure on journalists to produce quick headlines is at odds with the scientific world’s more measured approach.

Advice for stakeholders

A multi-pronged approach to tackling mis- and disinformation has been in full swing throughout the pandemic — labeling and fact checking, supporting journalists, grassroots campaigns. This showed the developments that can be made by the media and technology companies. As noted in the opening, the crucial role journalists play in countering policial falsehoods as well as slowing down mis- and disinformation should be further developed and supported, rather than the current “he said/she said” and traditional “horse race” reporting during elections. We encourage future outreach programs (from training to research to public media literacy) to help prepare audiences for misinformation.

This report also challenges politicians to consider their roles in the possible spread of falsehoods, blurring of lines and instigating misinformation during campaigns. Also encouraged is further discussion with policy makers and legislators to consider the mis- and disinformation vulnerabilities that arise from the lack of political advertising accountability in Australia.

Further research into Australians’ understanding of definitions and the effect this has is required. As noted above, there is a risk that claims of something as ‘misinformation’ may be a political bias or misunderstanding of the definitions. Yet these same audiences must also have easy access to full context and quality information.

First Draft also recommends more time and resources in newsrooms and media literacy programs be placed on prebunking and misinformation ‘inoculation’. We have an extensive guide available here.

This Australian misinformation election playbook was conducted with support from Meta Australia.

Reference

Allison Berke. Forum Response. Preventing Foreign Interference Is Paramount: The threat of election interference by foreign actors is fundamentally different — and more distressing — than the threat of domestic misinformation. Boston Review https://bostonreview.net/forum_response/allison-berke-preventing-foreign-interference-paramount/