The UK general election campaign has brought no shortage of mis- and disinformation, which has kept the First Draft newsroom busy. In between all the work monitoring, identifying, verifying and writing about disputed claims on various platforms, there’s another important piece of the process we wanted to highlight: the difficult task of making reporting decisions on the disinformation we’ve found.

The mere act of reporting on mis- and disinformation always carries the risk of amplification. Shining a spotlight on false or misleading information — even if it’s to call it out as false or misleading — can spread it to a wider audience, potentially resulting in more harm than good. In many cases, this extra publicity from established media outlets is exactly what disinformation agents want.

Deciding when and how we report on disinformation, so that we avoid or minimise amplification as much as possible, is crucial.

The tipping point

At First Draft we often refer to the ‘tipping point’, when the benefits of highlighting the background and details of a hoax outweigh the harms that may come from reporting it. This can vary — country to country and story to story – but a strong sign can be when a falsehood moves beyond the community it originated in.

Take, for example, the hoax about Liberal Democrat leader Jo Swinson shooting squirrels that spread earlier this month. First Draft first became aware of this on November 2, but waited over two weeks before publicly reporting on it.

First Draft added the overlay to the screenshot of a hoax about Jo Swinson

Though it felt counterintuitive to see blatant disinformation and not immediately sound the warning bells, we had to look carefully at the circumstances of the hoax and balance the public interest in the story against the potential consequences of amplification.

In the case of the squirrel hoax, getting the timing right was key.

On November 2, First Draft first noticed a tweet captioned “jo swinson: squirrel killer”. Under which the twitter user had attached fabricated images of a Daily Mirror article claiming there was footage of Swinson shooting squirrels with a slingshot.

This tweet was shared almost 1,000 times, with many of the shares coming from anonymous pro-Labour accounts, and some replies from confused users asking for the original source of the article, or complaining that the people cited in the alleged Mirror article were made up. We knew that this was definitely disinformation, but we decided it hadn’t reached the tipping point yet — spreading it would have exposed it to a much wider audience than the trolls who were populating the replies under the original tweet. We decided to keep an eye on this hoax, to see if it would travel.

Then, on November 5, a Medium post entitled “Swinson condemned for cruelty to squirrels”, written by “Miranda Joyce” of the “Milngavie Times”, was posted. This publication does not exist. “Miranda”’s photo was a stock photo of a “woman thinking”, which we discovered when we ran it through a reverse image search.

The Medium post was not widely shared until November 14, when a Brexit Party Twitter account with nearly 9,000 followers posted it. We noticed that Pro-Brexit Facebook groups also shared the post — nearly 4,000 times, racking up 20,000 interactions, according to social media monitoring tool CrowdTangle.

It was shared nearly 4,000 times on Facebook, largely by private accounts, but also by a lot of pro-Brexit pages and groups. It picked up more than 20,000 interactions, pic.twitter.com/KOqnkmrIcE

— First Draft (@firstdraftnews) November 19, 2019

The story was inching closer to the tipping point, as it had jumped platforms from Twitter to Medium to Facebook. But, after several conversations in the newsroom, we decided it still hadn’t quite reached it yet, since it was circulated on Facebook by mostly partisan groups. There were still some concerns that if we wrote about the story now, we’d be giving additional oxygen to the falsehood.

Then, on November 19, a day after a Facebook page called “Brexit News” shared the Medium post, Jo Swinson was asked about the claim on radio station LBC.

For First Draft, that was the push over the tipping point — the story had crossed over into establishment media, and the politician at the centre of the false claim had directly addressed its veracity and its spread. At that point, the hoax was no longer just the chatter of a small, niche audience. It was before a mainstream audience, and we felt that we could do more good in explaining what we knew about the hoax.

For every rumour or hoax First Draft discusses publicly, there are multiple others we monitor but ultimately choose not to write or tweet about.

Here are some questions which can help determine where the tipping point is, and whether or not to write about false or misleading content:

- Who is the audience for the story I would write about this disinformation? Is it likely they have seen the content in question already?

- Have I seen the false or misleading content across multiple platforms?

- Has a prominent figure addressed or spread this content?

- Has the content been addressed in media outlets with a large audience?

- How much engagement does the content already have? How quickly is it picking up interactions on a platform, and how do these numbers compare to similar content on the platform?

Images

Another discussion that has come up quite frequently at First Draft this campaign season is the responsible use of images.

As part of our reporting, it’s best practice to include evidence of any false or misleading claims. We want to show our audience what we’ve found, where we found it and how we know it’s mis- or disinformation.

However, we also don’t want to confuse readers. We want to signal to our audience — including those who are quickly scrolling through a story or flipping through their social media feeds — what is genuine and what is not.

And we don’t want to repeat any misleading claims. If we think there is a chance that someone could copy or embed something we’ve identified as false and spread it around further — whether inadvertently or knowingly — we take pains to overlay images with colour and text clearly indicating the problem.

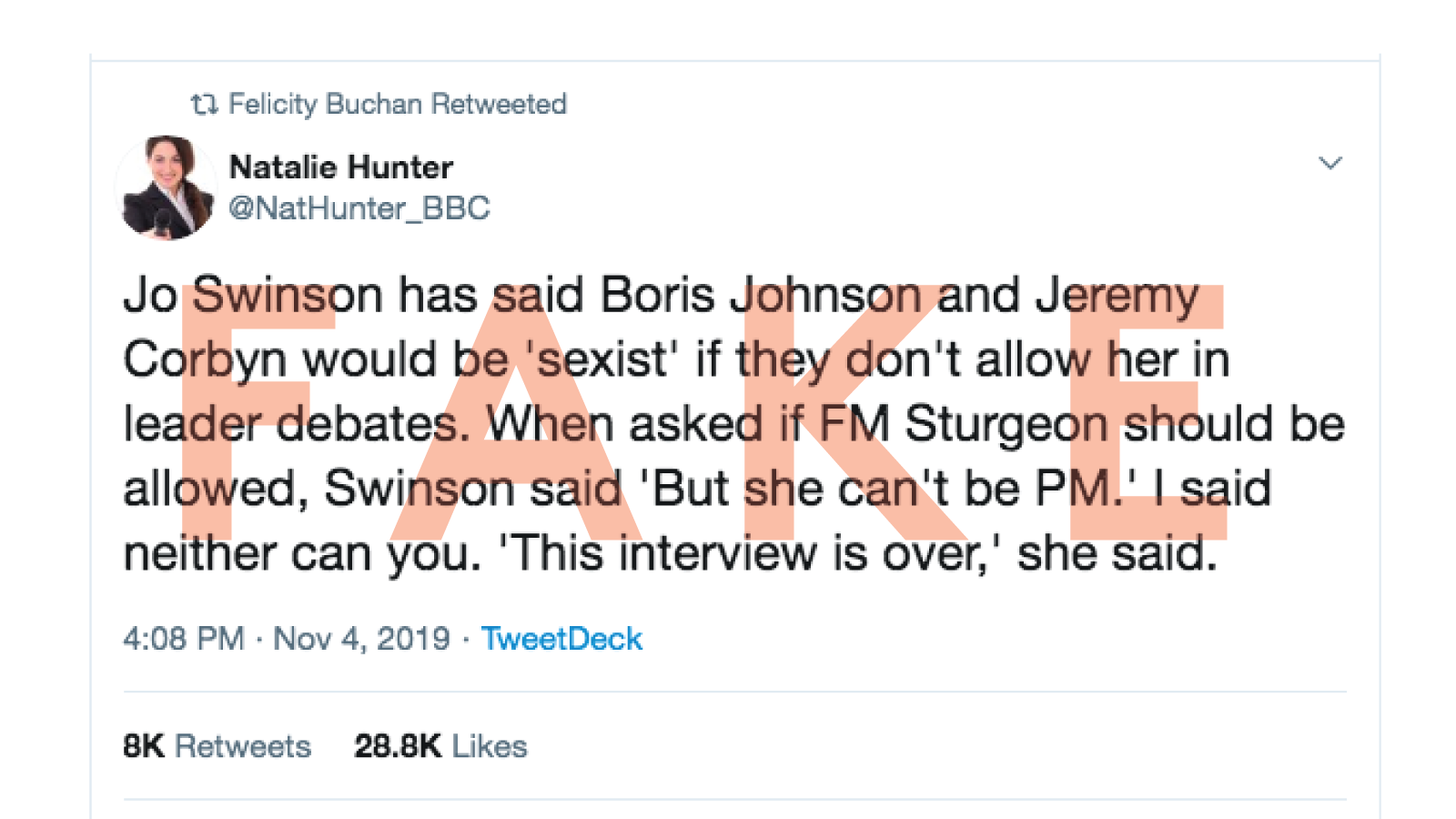

The November 5 piece about a fabricated quote from Jo Swinson, which was propagated by a Twitter user posing as a BBC reporter, is a prime example.

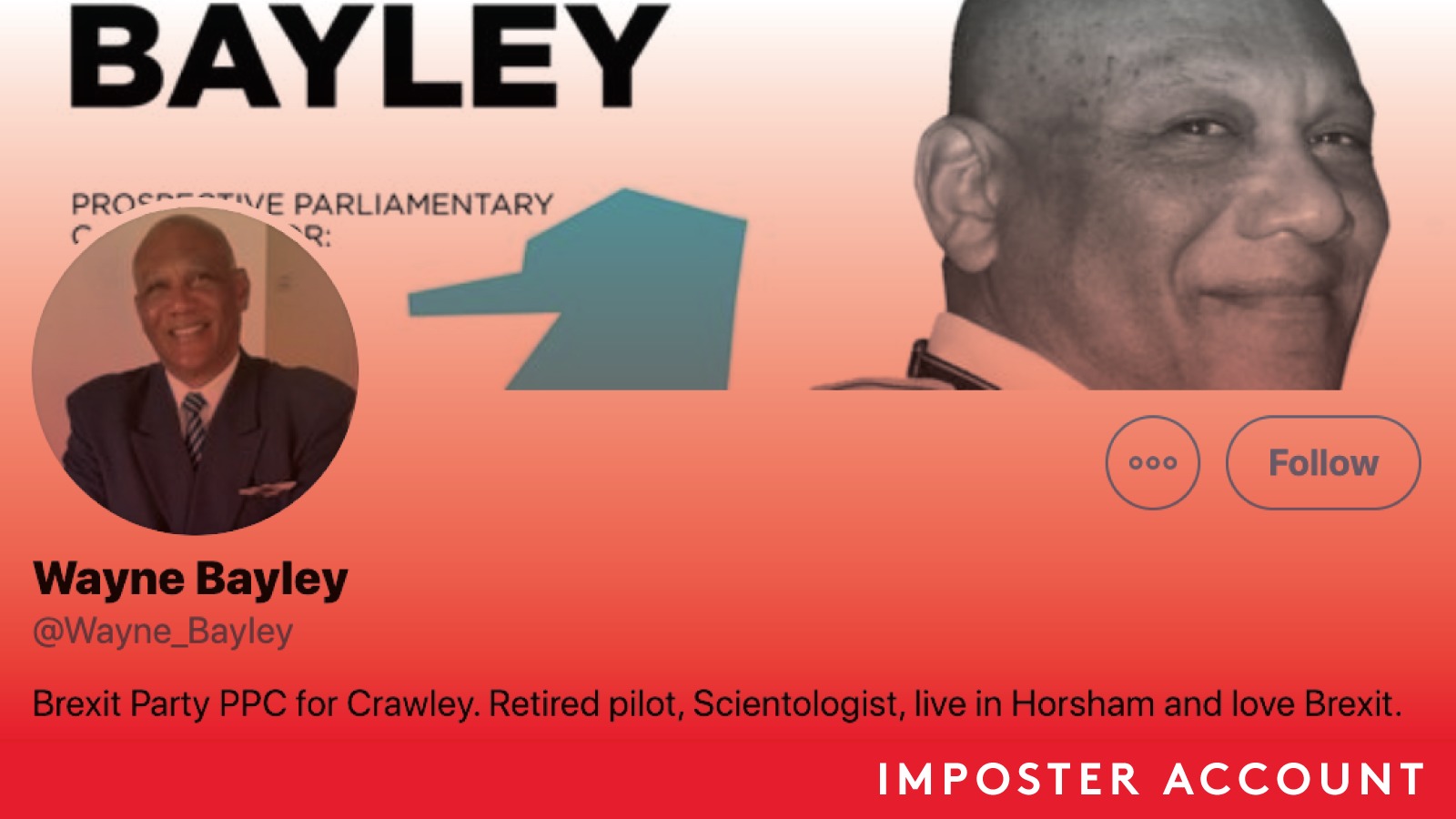

Similarly, our November 13 story about an imposter account that impersonated a prospective parliamentary candidate from the Brexit Party.

We contrasted this imposter account with the genuine account of the candidate by overlaying the image of the real account with the colour green and the word “trustworthy”.

And the November 21 write-up about fake newspapers that political parties were circulating in 13 constituencies.

‘Fake’ newspapers have been posted through voters’ letterboxes in the run-up to the UK general election on December 12. Image by First Draft

Even if our audience skims the text of the stories, a quick glance at the images with red text or overlay lets them know it is disinformation, and that they should not trust these accounts or materials if they encounter them in the future.

Similarly, instead of sharing plain screenshots or quote-tweeting misleading accounts on social media, the overlay ensures that the truth travels with the lie and gives readers and social media users the most accurate possible information while limiting the spread of the falsehood.

Links

Generally, our policy at First Draft is to include a link when we reference an external website, as a matter of transparency.

In some situations, however, we deliberately choose not to link to social media profiles or sites that could mislead readers, or which we know carry disinformation, in order to prevent the further spread of misleading or false information.

Returning to the November 5 analysis of fake persona “Natalie Hunter” and the fabricated Jo Swinson tweet, we elected not to link to the tweet, the Twitter account or the website for “BBC Scotlandshire” (where “Natalie Hunter” allegedly worked). Even though the site for “BBC Scotlandshire” contains a disclaimer in the footer characterising its content as “news items which are often ridiculous”, “generally fictitious” and “entirely ill-informed”, the site’s colours and layout bear significant similarities to the BBC News website. We decided the chances of misleading or confusing readers were high enough to justify foregoing the link.

Rather, we used screenshots of the fake persona’s tweet, along with an image overlay pointing out the fabrication.

In our November 13 piece on the imposter Wayne Bayley Twitter account, we did not link to the account, but used a screenshot (with an image overlay) and linked to a web-archived version of a profanity-laced tweet that the fake “Wayne Bayley” had posted.

In our November 26 roundup of misleading websites purporting to be from political parties, we used no-follow links. No-follow links involve adding a “nofollow” attribute to the HTML of a link.

In the article, no-follows will look and function like regular links, allowing readers to click through to the website carrying the false or misleading information. However, search engines do not take account of these links when assessing the search ranking of the destination page.

So, using no-follows helps prevent misleading sites from climbing up the results page and appearing near the top of searches for genuine information on the subject.

We decided to include screenshots from the sites in our article and to use no-follow links — as opposed to not linking to the sites at all — after discussing the sites’ likely appeal to our audience. Would our average reader be interested in seeing these sites for themselves? Even if we did not provide a link, how likely would readers be to then search for the sites, which would boost the sites up in the search results?

Our calculation was that readers would be interested in seeing the sites, given their newsworthiness and the fact that they were the focal point of the article. We set up the no-follow links in the HTML version of the post, and made sure the published post included a couple of sentences explaining no-follows and why we were using them. We wanted readers to understand what they were looking at and the consequences (or, non-consequences) of clicking through.

There are few easy answers for the “when” and “how” of reporting on disinformation, particularly when we factor in the breakneck speed at which the UK election campaign cycle has unfolded. Every responsible reporting decision over the course of the CrossCheck UK project thus far has involved a balancing act between timeliness, clarity, transparency and the need to avoid amplifying those who are trying to get their mistruths in front of a large an audience as possible.

Interested in becoming a CrossCheck partner? Get in touch.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.