Online hoaxes often share the same characteristics and are created and deployed using the same tactics. If you spend enough time tracking and debunking hoaxes, your nose for sniffing them out gets more refined and you’re less likely to fall for them.

But not all of us can dedicate months or years to hunting and documenting hoaxes. So here are some of the things I’ve learned over the years.

1. Timelines don’t add up

People perpetrating a hoax often have to construct a backstory in order to build credibility. This may involve creating a history for a company, person, or other entity. The farther back they go to establish credibility, the more likely they are to make mistakes.

A really simple example of this is a hoax that claimed a research company had found proof that users of Internet Explorer had a lower IQ than those using other web browsers.

The company cited in the press release said it had been in business since 2006 but a quick Whois search on its domain name showed that it had only been registered weeks before. Their backstory fell apart with just a simple search. (Unfortunately, the story was written up far and wide before being debunked.)

2. Names and people are problematic

The names and people cited in hoaxes often have gaps in their history, and offer a very thin profile. This is because most of the time they simply don’t exist.

Take, for example, the lawyer who was cited as representing Jay Z and Beyonce in their quest to buy the rights to the Confederate flag. This hoax story relied on quotes from lawyer ‘Ralph Hammerstein’. Online searches for lawyers with that name come up empty, as would searches of licensing databases in the relevant states. There is no such lawyer, let alone one of the profile one would expect of someone who represents Jay Z and Beyonce.

Or think of Jude Finisterra. That was the name used by one of the Yes Men who pretended to be a spokesman fom Dow Chemical in the famous 2004 Bhopal hoax that fooled the BBC. An online search or call to Dow headquarters would have found that no one by that name worked for Dow. (The Yes Men also chose a name that had some significance built into it: Jude is the patron saint of the impossible and Finisterra means earth’s end. Sometimes hoaxsters also use names from literature.)

Finally, pay close attention to photos used as headshots or avatars for people. Hoaxsters often use photos from other events or from social media accounts to go with their fake characters. A reverse image search is a fast way to see if that really is a photo of the person they say.

3. It appeals to a specific group or ideology or is too perfect

Humans love to hear things that we already believe. It is immensely comforting for us to be told information that conforms to our existing beliefs and knowledge.

Hoaxes often appeal to pre-existing beliefs in order to make people more likely to willingly accept and propagate them. North Dakota named a landfill after President Obama? Obama haters might love that idea so much that they won’t bother to read it more closely.

In a similar vein, stories that fall into the too-good-to-check category are so irresistibly perfect/ironic/amusing that people feel compelled to pass them on. Case in point: Jay Z and Beyonce buying the rights to the confederate flag. Or the viral hoax that claimed Abraham Lincoln had invented his own, low-tech version of Facebook back in his day. Both are too perfect.

4. It has the trappings (and only the trappings) of authenticity

A hoax has to find ways to convey a sense of credibility. Fake news articles often cite other media reports to back up their claims, but they will not link to these (non-existent) articles or they’ll simply inset links that go to the homepage of the website they mention. Their bet is that most people won’t take the step of actually clicking through.

Hoaxsters will also often invent the name of police officers or others in positions of authority, and inset quotes from them. The North Dakota landfill story, for example, quoted two state senators that do not exist.

5. It falls apart when you focus on the details

Click all of the links, Google all of the names, reverse image search all of the images, run a Whois on the domains mentioned. This is how you’ll find the loose thread that untangles the whole thing. Every piece of information offered is a detail to be examined. Something that reads as real will quickly fall apart in the face of a few clicks and searches.

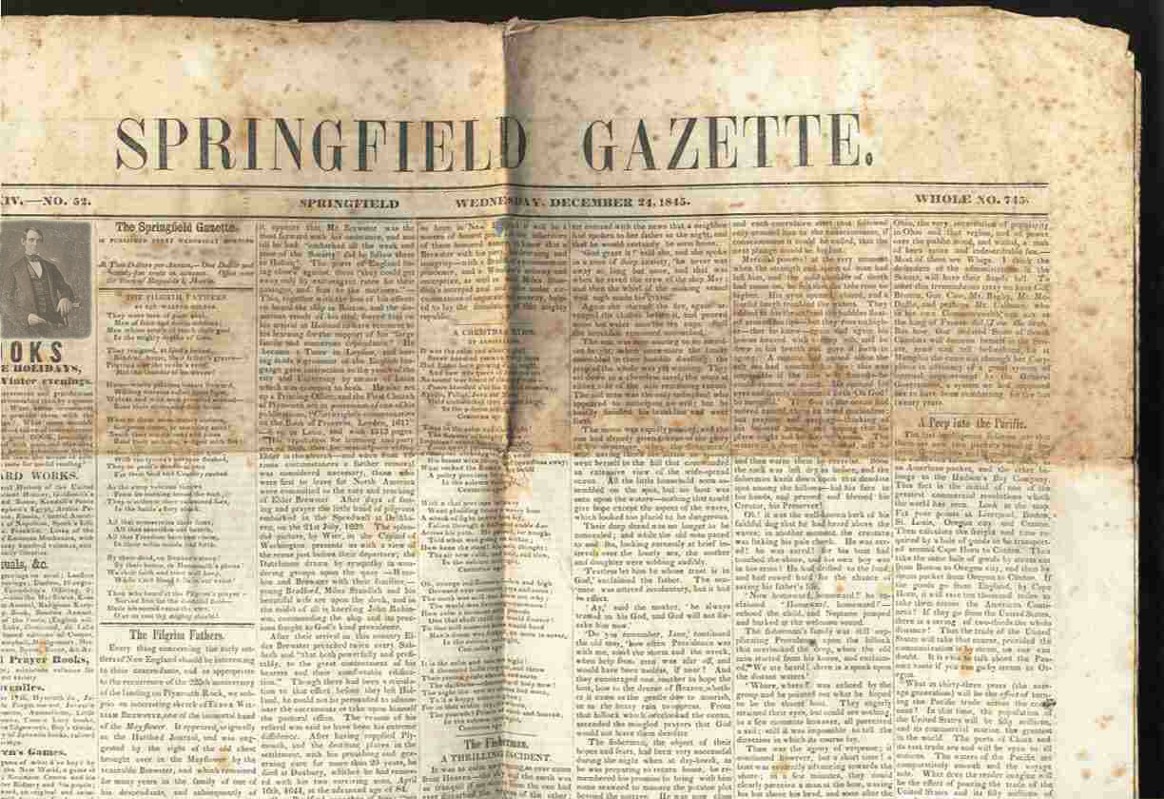

That Lincoln Facebook hoax I mentioned? The newspaper article that was used as a primary source included a telltale sign of fakery that was highlighted by a commenter on a post I did about the hoax:

The “newspaper” article in question:

From Hoaxes.org and widely circulated on Facebook