In June, Reported.ly published an exclusive investigation showing that retirement funds and other investors are profiting from the bombing of Yemen. The investigation traced a shipment of bombs made in Italy to armed forces involved in the bombing campaign. Bombs with the specific manufacturer codes were photographed on the ground in Yemen. Read the full investigation here.

The two-week investigation wove several documents, logs, photo and video evidence together, as well as expert analysis, background research and a number of validation techniques. These are mostly outlined below.

One of Reported.ly’s remits is to reach audiences where they naturally reside. Atoms of the investigation were peppered across social networks and the entire report was published in five languages across nine publications. Some lessons and insights to the considerations behind this are provided below.

The Jolly Cobalto

A leaked letter from Burkan Munitions Systems asked UAE armed forces to provide a “transit permit” for Jeddah Port. The document, dated April 2015, said “bomb accessories” were packed in six containers aboard a ship called the Jolly Cobalto.

Working with researchers at our sister publication, The Intercept, we found records on Equasis.org showing the Jolly Cobalto is a new container vessel delivered in February 2015 and owned by Ignazio Messina and Company. Messina’s website said the Jolly Cobalto is still under construction.

However, Equasis.org records an inspection of the ship on 29 April 2015 in Castellon, Spain.

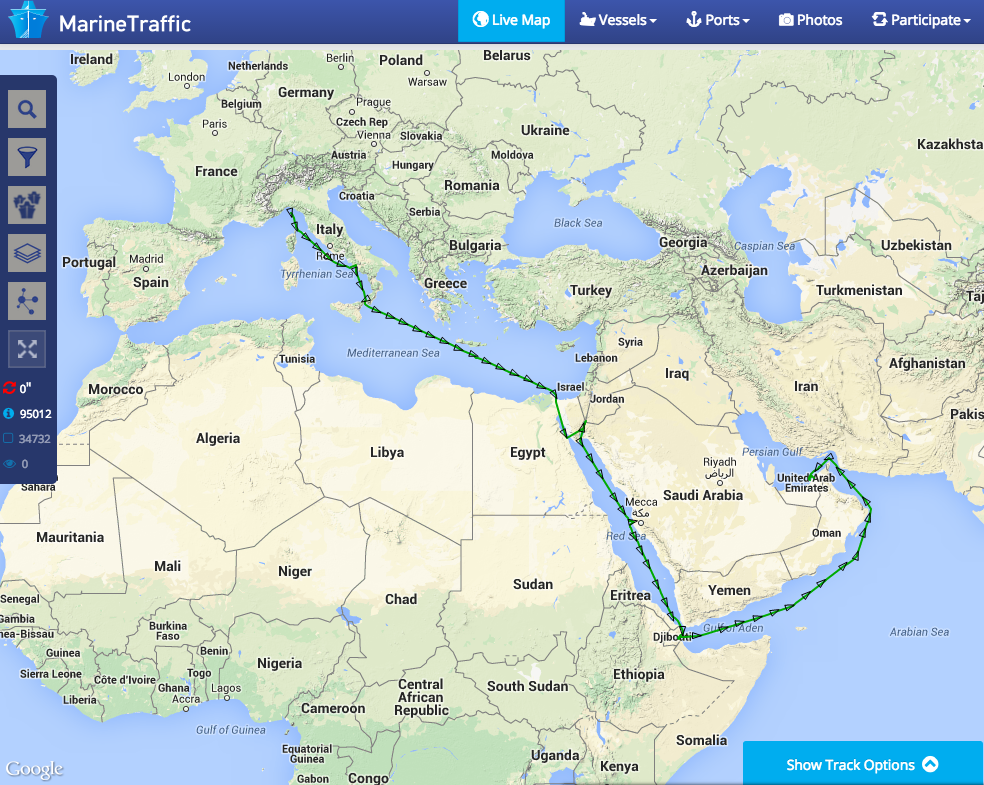

The route: Genoa — Suez Canal — Jeddah — Dubai — Abu Dhabi

The shipping document showed that the Jolly Cobalto was scheduled to depart Genoa and arrive at Abu Dhabi in May 2015. On the day the investigation started, June 12, 2015, MarineTraffic.com showed the Jolly Cobalto was sailing from Jebel Ali in Dubai to Iran. This confirmed it had passed from Castellon, where it was inspected, to the Middle East and that it was not under construction as the outdated Messina website suggested.

Looking at other ships in the Messina line, it was evident that several regular lines are routed from Castellon and Genoa to the Middle East.

A trial subscription with MarineTraffic.com gave me access to the 60-day history. This in turn confirmed that the ship did indeed travel from Genoa in May, through the Suez Canal to Jeddah. It docked in Dubai beside the iconic Palm Jebel Ali islands in early June.

This broadly tallied with the timing and route laid out in the document. And it established this as the maiden voyage of the Jolly Cobalto, which was important regarding the integrity of the documents.

The shipment

The Packing List detailed parts of MK82 and MK84 bombs made by RWM Italia. We confirmed that RWM Italia makes these parts by examining export licenses granted in 2012, 2013 and 2014 by Italy’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. We knew that RWM Italia has exported thousands of MK83 bombs in contracts over €100 million – this becomes relevant later on.

The shipment was bound for Burkan Munitions Systems in Abu Dhabi – this is the company that requested the transit permit through Jeddah port, therefore requiring sanction by Saudi Ministries. The shipment is required to fulfil a long-standing contract Burkan has with the UAE’s armed forces, one of the forces actively bombing Yemen.

Looking through Burkan’s slick promotional videos on YouTube, we know that the company manufactures US-designed MK80 series bombs.

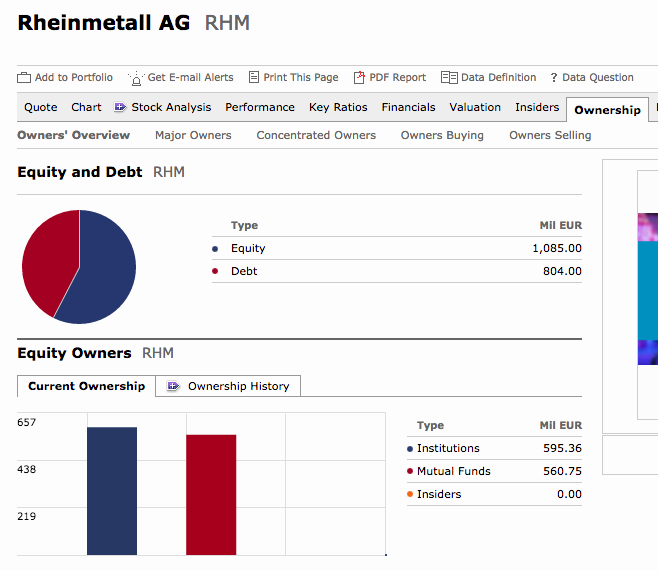

Burkan and RWM Italia were once owned by the same parent company, Rheinmetall Defence AG. An arms trade expert at Stockholm International Peace Research Institute told us the documents confirmed what he already knew – that Burkan remains largely dependent on European parts that are assembled at its plant in Abu Dhabi.

Shipment moves from Dubai -> Abu Dhabi -> arms manufacturer Burkan for the supply of bombs to UAE military. Watch: pic.twitter.com/cnilTkIUHt

— reported.ly (@reportedly) junio 25, 2015

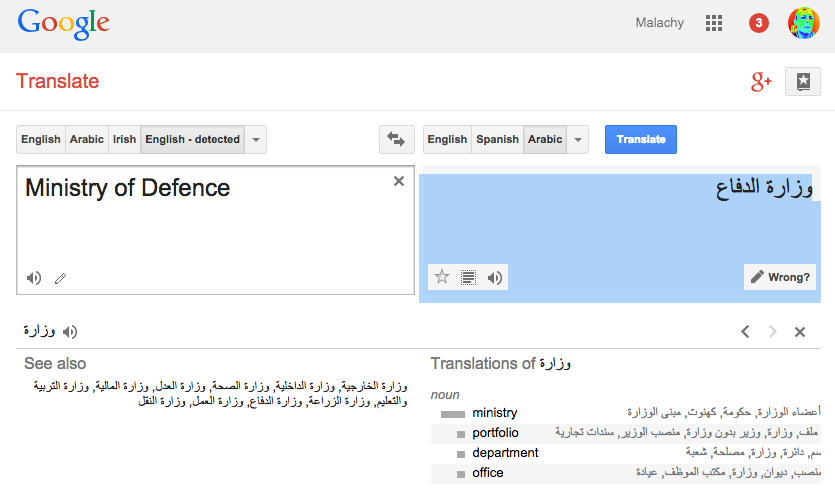

The integrity of the cable

The cable is one of thousands hacked from Saudi ministries by an unknown group naming itself the Yemen Cyber Army. Tens of thousands of leaks have since been published by Wikileaks; we are confident the documents are part of the same hack. Read more about this in the main story. We translated the Arabic cover letter of the documents with help from a trusted English-speaking journalist whose mother tongue is Arabic. Because of differences in Arabic script, we had this translation validated by Amnesty International’s Gulf section. The translation showed that the communiqué was being passed by Saudi’s Minister for Foreign Affairs to several other ministries, including Defence, Transport and the Deputy Prime Minister’s office. The cover letter is marked “extremely urgent” and signed by Adel Al Jubeir, who is the sitting Minister of Foreign Affairs. Several phone numbers listed on the documents also check out. The Hijiri date written on the cover letter in Arabic numerals is 14 7 (Rajab), 1436, which matches the Gregorian date of May 3, 2015 — the date on the telex. The telex header shows the sender as MOFA on each cover letter. One receiver is listed as WAZIR ALDIFA. For a non-Arabic speaker, type Ministry of Defence into Google Translate and listen to the Arabic translation — it’s Wazir Al Difa. Other recipients include the Saudi Port Authority, which tally with other addressees in the minister’s cover letter.  One of the cover letters may have an incorrect date matching 2014, but given the Jolly Cobalto did not exist in 2014, this is likely explained by a typographical error made in the rush of sending a “very urgent” telex.

One of the cover letters may have an incorrect date matching 2014, but given the Jolly Cobalto did not exist in 2014, this is likely explained by a typographical error made in the rush of sending a “very urgent” telex.

Bombs in Yemen

So far, the chain of evidence linked the active sale and supply of bombs to forces involved in bombing Yemen. And when I spoke with weapons experts at Human Rights Watch (HRW), we traced bombs made by this Italian company to the ground in Yemen. Ole Solvang, an experienced HRW researcher who features in the Netflix film E-Team (watch it!), photographed MK83 bombs with RWM Italia manufacturer codes in Sada’a, northern Yemen. Ole and his colleagues documented the illegal use of weapons with horrendous civilian fallout during their time there in May.

Additionally, @OleSolvang photographed these MK83s with RWM Italia labels at a government compound in Sa’dah, #Yemen pic.twitter.com/44vv1Dx3nn

— reported.ly (@reportedly) junio 24, 2015

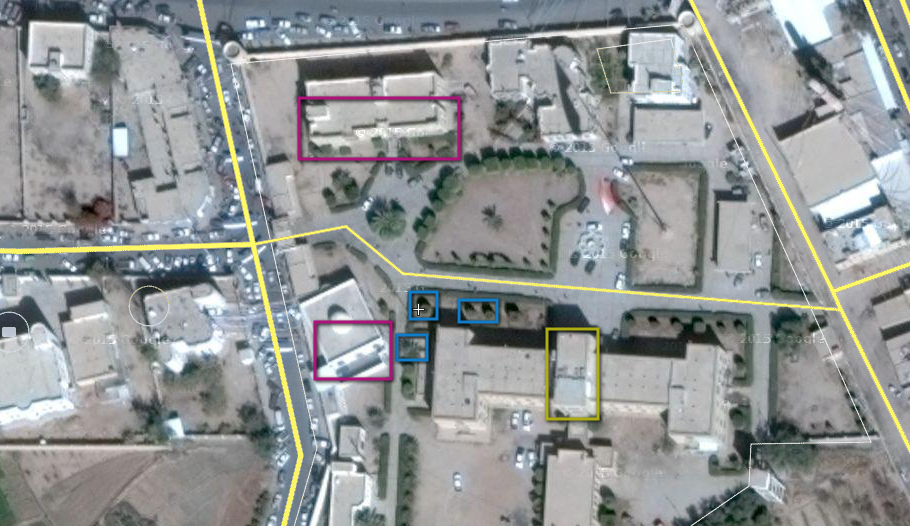

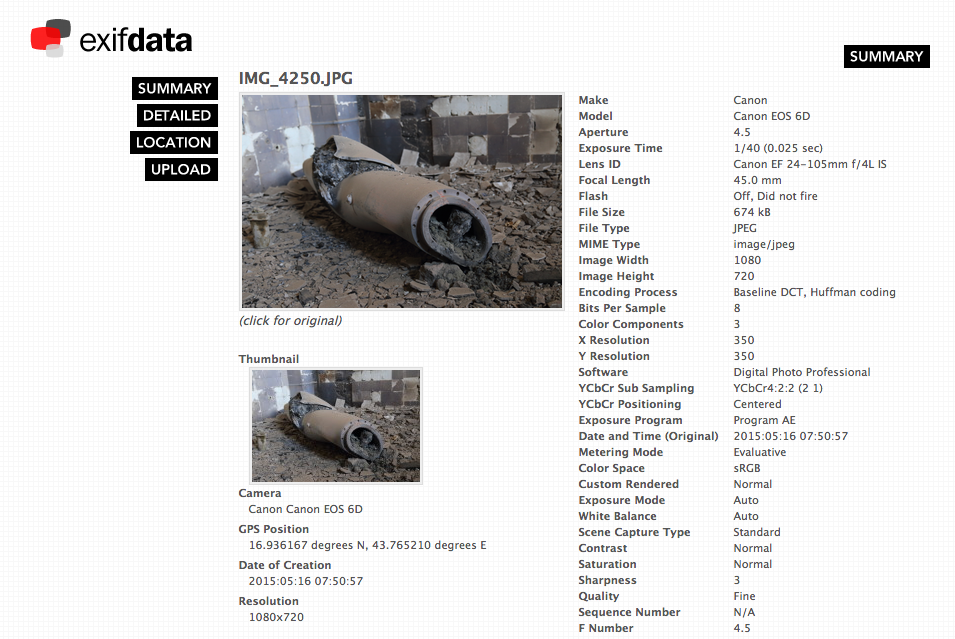

The photographs Ole emailed me contained GPS coordinates in the metadata showing the precise location they were taken. Uploading the files to the Exif Viewer exifdata.com gives the co-orindates and other information about the camera, date and time etc.  Ole said he photographed the bombs in a government compound in Sada’a, northern Yemen. Of course one trusts a researcher of Ole’s standing, but by plugging these co-ordinates into Wikimapia, you see the precise building. Indeed, the building is described on Wikimapia as Government Complex of the Province of Sada’a (in the city of Sada’a).

Ole said he photographed the bombs in a government compound in Sada’a, northern Yemen. Of course one trusts a researcher of Ole’s standing, but by plugging these co-ordinates into Wikimapia, you see the precise building. Indeed, the building is described on Wikimapia as Government Complex of the Province of Sada’a (in the city of Sada’a).

The diagonal white mosque, the large corner tree and low shrubbery bordering the main building (blue), two smaller trees in front of the building and a palm tree further along the side (blue). The top of the elevated middle section is highlighted in yellow.

The rear of the white mosque also matches, showing a section that doesn’t extend across the full width of the mosque (purple), and a tall building across the square in the background (purple).

Follow the money

Bombs are shipped from Italy to be dropped in wartime. So what? A key part of this investigation was to show how many of us unwittingly profit from this activity. RWM Italia is owned by German company Rheinmetall Defence AG, which has been involved in other controversial sales and deals.

A financial source provided some initial information about the Rheinmetall’s shareholders and the extent to which they were invested. The New York State Retirement Fund and Norway’s State Pension Fund are among them, as are almost 200 other funds and institutions including the largest college fund in the U.S.

The Morning Star website allowed us to examine some of these in greater detail. We intend to follow up on this aspect of the investigation.

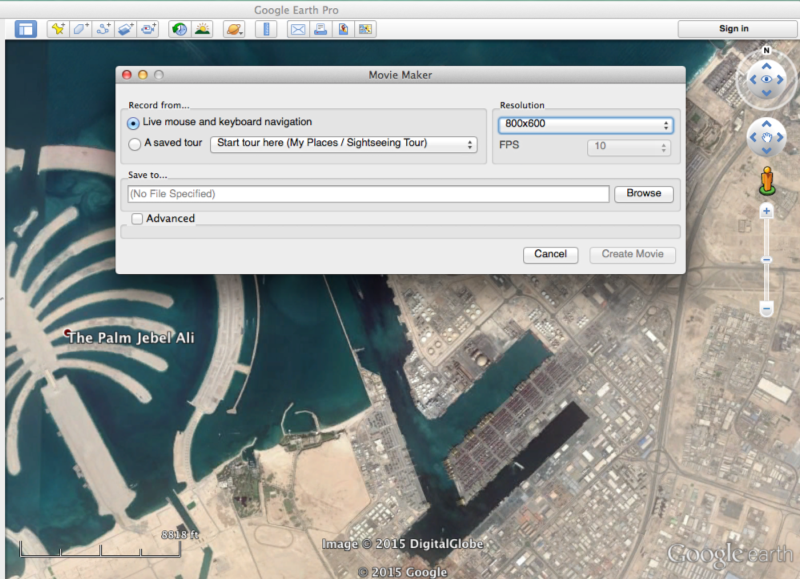

Google Earth tour

To help people visualize the geographic scope of the story, we turned to Google Earth to create a virtual tour of the locations involved. Because of Google Earth’s high-resolution satellite imagery, it’s possible to see the various locations referenced in the story, from the factory that manufactured the bomb parts in Sardinia to buildings that were bombed in Yemen.

There are two ways of recording a Google Earth tour, both involving its Movie Maker feature. Movie Maker lets you record a tour manually — capturing your map’s movements as you click and scroll with your mouse — or automatically with a pre-programmed route. Given the precision we hoped to achieve — zooming into specific buildings, hovering over locations at a particular altitude and heading — we opted for the latter method. It’s more labor intensive, but avoids problems like accidentally recording wrong turns when using a mouse.

To create an automated tour, you first have to create a KML file. KML is the markup language used to capture geographic data. We created a KML file containing all the exact movements we wanted the tour to make. For example, the file would include latitude and longitude co-ordinates in conjunction with altitude data to begin the tour at a particular location, floating high above the Mediterranean.

Then, we could program the file to jump from location to location, using more lat/long coordinates along with altitude, heading, camera angle, speed and other factors. It’s the equivalent of telling Google Earth: start here, turn 90 degrees, pause for 3 seconds, fly to a second location over the course of five seconds, pause another three seconds, zoom to ground level, etc. It’s a bit labor intensive — you have to test each coordinate again and again until you get it exactly right — but it allows you to control the tour with a level of precision you can’t get while using your mouse and keyboard.

With the final KML file complete, we opened it in Movie Maker, then had it record a high-resolution mp4 file. Once it was saved, it was just a matter of importing the mp4 file into video editing software, then getting to work creating the final video.

Lessons

- Facebook video needs text overlay. We crafted what I think is a fast-paced, visual video with a Google Earth tour made by my colleague Andy Carvin. But without text overlay, there was no incentive for people to click on it when it autoplays in their feed. The same is true of YouTube video delivered via Twitter.

- Visual social atoms work. A day after we published the story, we posted individual tweets summarising key evidence in each stage of the investigation. Most of these had a visual aid — a video or image. For video, I did this using iMovie to cut the segments, saved to Dropbox, copied to My Photos on my iPhone, and tweeted pictures and videos from Reported.ly’s Twitter account. (There’s probably an easier way to do this!).

While we don’t live by engagement tricks, statistics show that Reported.ly’s engagement on visual tweets is multiples of text-only tweets. So when you have good journalism to promote, do what you can to reach an audience. Final note on this: people love maps.

Historical shipping data on @MarineTraffic verified the route of the bomb parts from Genoa-Jeddah-Dubai in May pic.twitter.com/8OSXTXIJyB

— reported.ly (@reportedly) junio 25, 2015

- Thread. Reported.ly is a social-centric publication. That means we publish to social networks before our website, usually. Twitter can be somewhat ephemeral; a tweet is lost in the torrent. Keep topical collections of your Tweets together by threading — replying to the tweet that went before. This solves the stock and flow problem. All of my social atoms for this investigation are in this thread.

- Share! And collaborate! The temptation for journalists investigating something like this is to keep secrets safe, particularly as more evidence surfaces. In sharing everything I had with the 20 or more people I spoke to, they gave back in spades and the investigation developed every day. The folks I spoke with have an interest in this area, and because the chain of evidence was compelling and somewhat rare, being generous in the first instance was rewarded. And everyone respected Reported.ly’s wish to publish first.

- Acknowledge. We thanked everyone who wanted to be thanked in the article, and withheld the names of those who wanted to remain anonymous.

Websites and resources used

What is outlined above is not an exhaustive list of steps taken. Rather, I focus on the more technical steps to show what tools are available. Further background and research was done with these tools, good old Google, and by picking up the phone, lots! Resources: MarineTraffic.com, Google Earth Pro, Arachnys, Lexis Nexis, cat-uxo.com (experts forum on unexploded ordnance), Facebook Groups (on Yemen and Munitions), Getty Images, Google News Search, YouTube, Wikimapia, DocumentCloud, iMovie, Dropbox, Google Translate and volunteer translators, Google Translate.