Two middle-aged men — dirty, beaten and bare-chested — sit against a red brick wall. Fear in the eyes of one, resignation lines the face of the other. A figure in military fatigues stands over them, revving a chainsaw that he raises to their necks, while an off-camera voice barks orders in Arabic.

The video depicting this scene and its grizzly denouement came out of Syria in 2012, claiming to show militants loyal to President Assad executing their Sunni enemies. Unfortunately for its creators, who had smartly over-dubbed most of the sound, the original footage was filmed by a Mexican drug cartel.

“Finding the first upload of a video is the first step to verifying it,” said Cynthia Fang, a research student at MIT, speaking at a recent TechRaking event at the university. When it comes to footage alleging war crimes, publication without verification can lead to foreign involvement, air strikes and further misery.

“Obviously it’s a very time consuming process,” she said, and especially when such horrors are involved, “so automating it could save a lot of time and energy for a journalist.”

Such a process already exists for photos of course, with reverse image search tools from TinEye and Google both widely used by newsrooms to trace a picture’s online history.

Screenshot from TinEye.com

Upload the image in question, or just copy and paste a URL, and both tools will show where that or similar images may have appeared on the Internet before. Easy.

But reverse video search would be too “computationally expensive” said Fang. Searching for the thumbnail of an image may help, but analysing all the frames in a video and all the frames in all potential matches is just not practical or efficient, so other methods are necessary.

As detailed in the Verification Handbook, the keywords of a video are most likely to yield relevant results in a search — these might be in the description in the YouTube video, in its title or by searching the videos URL on Twitter and seeing what words people are using to describe it.

This last summer Fang built a prototype to automate the whole process.

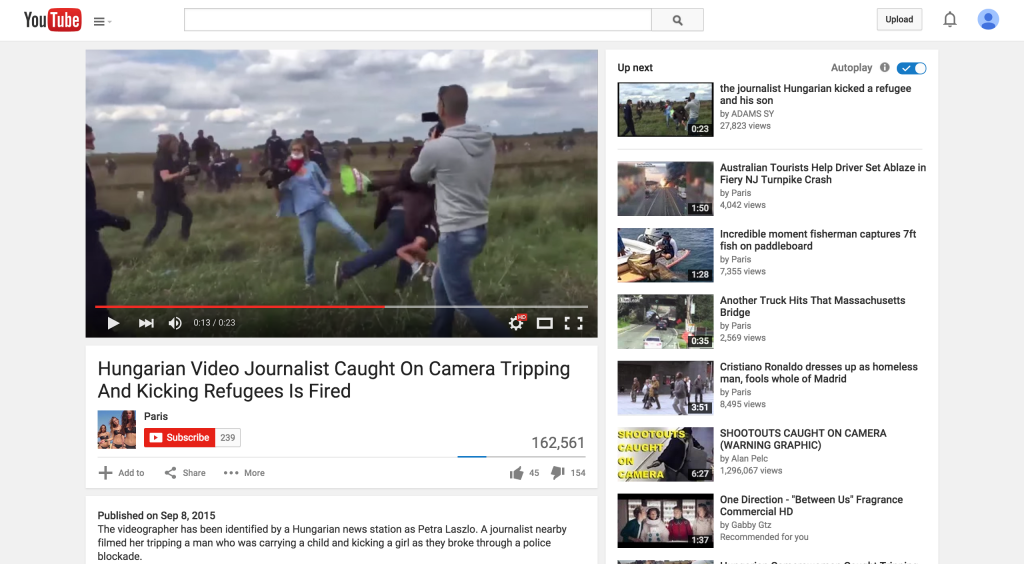

When a Hungarian camerawoman was filmed kicking out at refugees fleeing from police the world was shocked, but newsrooms needed to get as close as possible to the original source to check whether the footage was real.

By entering the URL of the relevant video into the search field of the prototype it will begin the process of looking for previous examples.

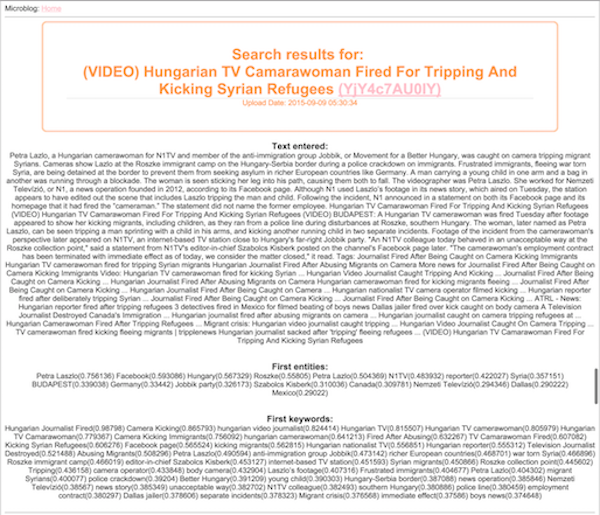

“It returns a list of entities and keywords ranked by importance, gives it a score of 0 to 1 using a machine learning algorithm and then take those entities and keywords of high importance and YouTube searches them again,” she said, automatically identifying keywords and ranking them in importance.

Screenshot from Fang’s prototype, detailing the video’s accompanying text, keywords and entities

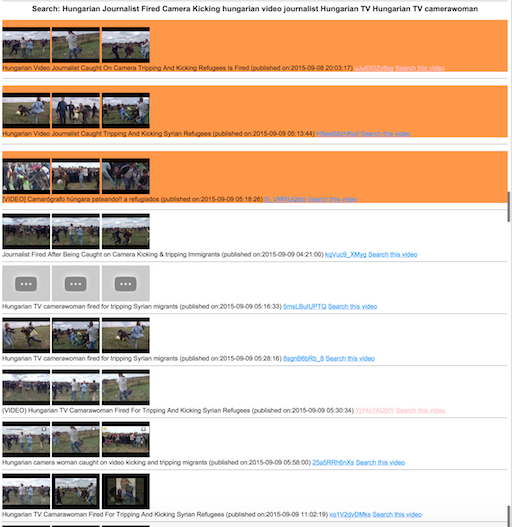

These keywords are then used to search the relevant platforms and identify any videos uploaded before the video in question, displaying them in orange, allowing the user to start the search again with the earliest result to double check there are no earlier matches.

The search results, with earlier videos marked in orange

Finding the earliest example of a video is just one step, the first step, in identifying whether it is legitimate and will never fully determine a content’s veracity by itself.

Fang still wants to improve the search function, adding other video sites beyond YouTube and the capability to search in different languages, but speeding up the process and reducing the need to view horrific images over and over could go a long way in helping newsrooms in their verification workflow.

Check out the First Draft visual verification guide for photos and videos for other ways to verify material from social media.

Cynthia Fang was speaking at a #TechRaking event organised by the Center for Investigative Reporting and held at the MIT Media Lab in Boston.