This is the fifth in a series of new Essential Guides published by First Draft. Covering newsgathering, verification, responsible reporting, online safety, digital ads and more, each book is intended as a starting point for exploring the challenges of digital journalism in the modern age. They are also supporting materials for our new CrossCheck initiative, fostering collaboration between journalists around the world.

This extract is from First Draft’s ‘Essential Guide to Closed Groups, Messaging Apps and Online Ads’, by Claire Wardle, Rory Smith and Carlotta Dotto.

Download the full guide:

In 2016, the social networks, search engines, newsrooms and the public were not ready for election-related misinformation. From the headlines pushed by Macedonian teenagers, to the Facebook ads published by the Russian Internet Research Agency, to the automated and human coordinated networks pushing divisive hashtags, everyone was well and truly played.

Three and a half years later, there is more awareness of the tactics used in 2016, and measures have been put in place. Google and Facebook changed their policies making it harder for fabricated ‘news’ sites to monetize their content, Facebook has built an ad library so it’s easier to find out who is spending money on social and political advertising on the platform. Twitter has become more effective at taking down automated networks.

It is unlikely, however, that the same tactics we saw in 2016 will play out in 2020. The technology companies have strengthened their policies and rolled out projects like the Facebook Third Party Fact-Checking project to down-rank false content in the newsfeed, and invested in additional engineering resources to monitor these threats. But those who want to push divisive and misleading content are devising and testing new techniques that won’t be impacted by the new platform developments.

While it’s impossible to know exactly what will happen in 2020, one of the most worrying possibilities is that most of the disinformation will disappear into places that are harder to monitor, particularly Facebook groups and closed messaging apps.

Facebook ads are still a concern. One of Facebook’s most powerful features is their advertising product. It allows the administrators of a Facebook page to target a very specific subsection of people, like women aged between 32-42 who live in RaleighDurham, have children, have a graduate degree, are Jewish and like Kamala Harris’ Facebook page, for example.

Facebook even allows ad-buyers to test these advertisements in environments which allow you to fail privately. These ‘dark ads’ allow organizations to target certain people, but they don’t sit on that organization’s main Facebook page — making them difficult to track. Earlier this year Facebook rolled out their Ad Library which gives some ability to look at the types of ads certain candidates are running, or to search around a keyword like ‘guns’. We explain how to use the Ad Library later in this guide.

Another major threat is going to be damaging or false information leaked to newsrooms for political gain. In France, in the lead up to the Presidential election in 2017, documents purported to be connected to Macron’s financial records were leaked 44 hours before the election. In France, a law prohibits news coverage of candidates and their supporters in this period and the French newsrooms agreed to stick with the law, meaning the leaked information did not get wider amplification.

In the US, the leaking of emails connected to Hillary Clinton and the Democratic National Committee staff and their publication in the weeks before election day took a different path. According to a study published in the Columbia Journalism Review “in just six days, The New York Times ran as many cover stories about Hillary Clinton’s emails as they did about all policy issues combined in the 69 days leading up to the election.”

An opinion piece in the New York Times by Scott Shane from May 2018, entitled When Spies Hack Journalism is worth a read. As Shane writes: “The old rules say that if news organizations obtain material they deem both authentic and newsworthy, they should run it. But those conventions may set reporters up for spy agencies to manipulate what and when they publish, with an added danger: An archive of genuine material may be seeded with slick forgeries.”

Overall, the threats are going to move to places that are a lot harder to monitor. In 2020, there are a number of countries that will have a reason to try to impact the election, not just Russia. And while everyone likes to focus on foreign interference, domestic actors — either campaign operatives, zealots for certain candidates, or those just trying to cause mayhem for the sake of it — will be mobilized as well. And there will be an intersection. As the tech companies have cracked down on foreign entities paying for ads, and clues like a foreign IP address are a potential red flag, we’re seeing the targeting of domestic actors and influencers as a way to push or amplify a message. So even if it looks domestic, it might have threads leading elsewhere.

If you haven’t seen the New York Times’ excellent documentary Operation Infektion about the ways today’s information operations mirror those of the KGB in the 1980s and 1990s, it comes highly recommended.

Why are these dark spaces so worrying?

In March 2019 Mark Zuckerberg talked about Facebook’s pivot to privacy. This description actually reflects what had already started to happen. Over the past few years people have moved away from spaces where they can be monitored and targeted. This is probably a result of users learning what happens when you post in public spaceswhether it’s children growing up and complaining that they never consented to those baby photos being searchable in Google, or people losing their jobs after drunk or just ill-considered tweets, or realising that law enforcement, insurance adjusters and Border Protection Officers are watching what gets posted, or the disturbing reality of online harassment, particularly targeted at women and people of color.

Some people are turning their Instagram profiles to private, others are reading the Facebook privacy tips and are locking down the information available on their profiles, and there’s more self-censorship on Twitter. In certain parts of the world, regulation aimed at punishing those who share false information might have a chilling effect on free speech, according to activists.

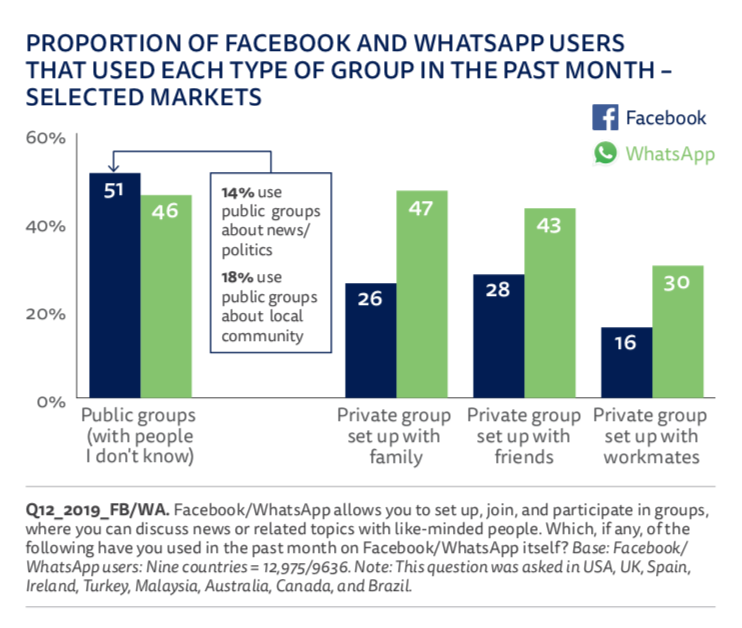

This shift is completely understandable, and we suspect historians will look back at the last ten years as a very strange and unique period where people were actually happy broadcasting their activities and opinions. The pivot to privacy is really only a transition back to the norm, having conversations with smaller groups of people, and those with whom you have a higher level of trust or affinity. This graph from the 2019 Reuters Institute Digital News Report shows how many people currently rely on groups on Facebook and WhatsApp for news and politics.

How Facebook and WhatsApp users rely on groups for news and politics, Digital News Report 2019

However, for journalists attempting to understand what rumors and false information are spreading to play a role in refuting and hopefully slowing down the distribution, this shift makes things very difficult.

When information travels on closed messaging apps, whether that’s WhatsApp, iMessage or FB Messenger, there is no provenance. There is no metadata. There is no way of knowing where the rumors started and how it has traveled through the network.

Many of these spaces are encrypted. There’s no way of monitoring them with a Tweetdeck or CrowdTangle. There’s no advanced search for WhatsApp. Encryption is a very positive thing. It’s vital that as a society we have these types of spaces, but when it comes to tracking disinformation, particularly disinformation that is designed to be hidden, like voter suppression campaigns, it starts to become quite worrying.

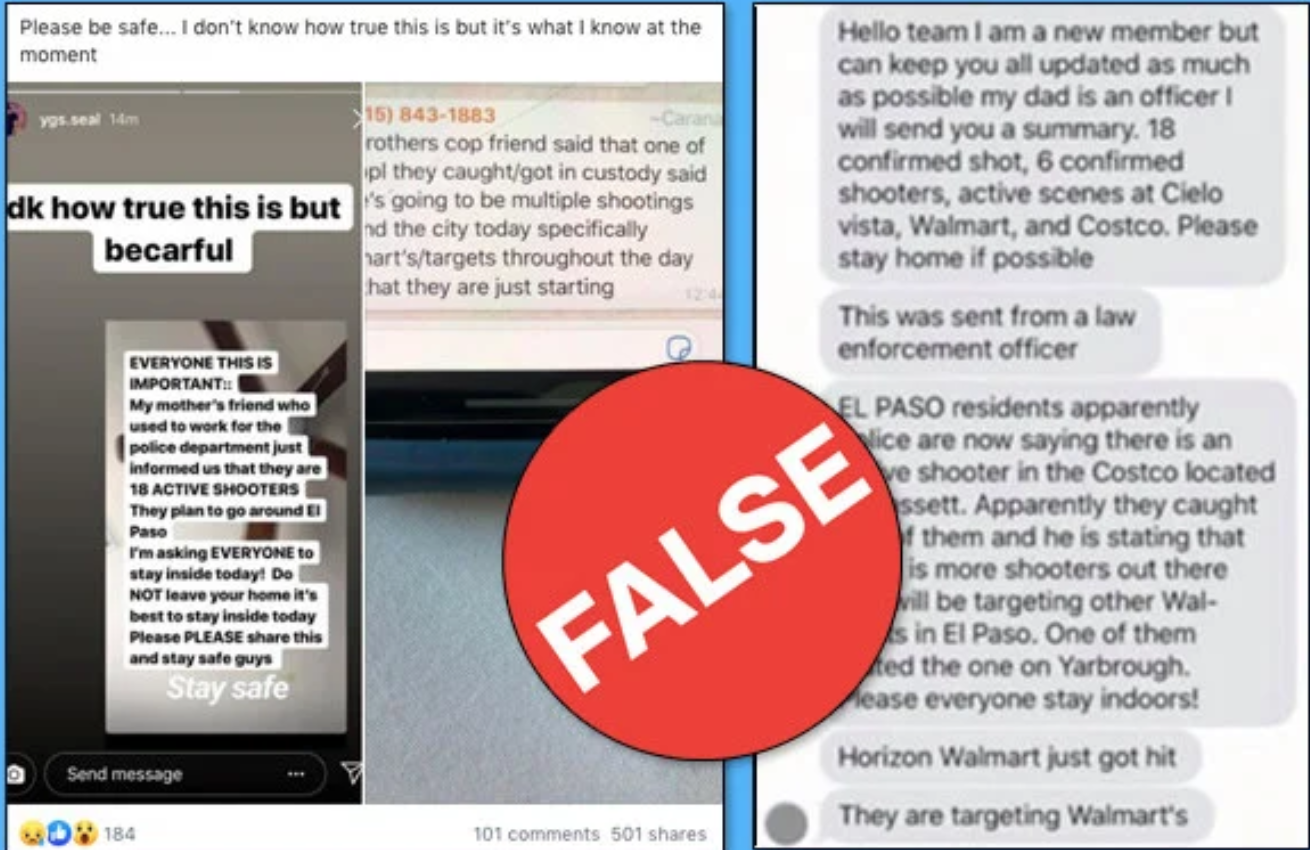

Jane Lytvynenko from BuzzFeed regularly tracks rumors and falsehoods during breaking news events. As she watched events unfold during the mass shootings in El Paso and Dayton in mid-August 2019, she saw for the first time significant levels of problematic content circulating in closed spaces including FB messenger, Telegram, Snapchat and Facebook groups. She wrote up her observations in BuzzFeed.

Misinformation about the El Paso and Dayton shootings circulated in closed messaging spaces

This shift in tactics creates a number of new challenges for journalists, particularly ethical challenges. How do you find these groups? Once you find them, should you join them? Should you be transparent about who you are when you join a group on a closed messaging app? Can you report on information that you’ve gleaned from these groups? Can you automate the process of collecting comments from these types of groups? We’ll tackle these challenges and more throughout this guide.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.