After months of reporting on the impact of misleading, manipulated and fabricated content spread among peers on technology platforms, we’re beginning to see governments and regulators grapple with these issues. It’s not a moment too soon, as it’s more important than ever that we start to think about information disorder from a more sophisticated perspective.

Back in February, Claire published an article where she outlined seven types of mis- and dis-information, attempting to underline the complexity of this subject. Today, after six months of work, we’re publishing a substantial research report, co-authored by Claire and the writer and researcher Hossein Derakhshan, that builds on that earlier thinking.

Commissioned by the Council of Europe, the report lays out a new definitional framework for thinking about information disorder, provides an overview of current responses and summarizes key academic studies on how people consume information, particularly fact-checks and debunks. It ends with thirty-five recommendations, targeted at technology companies, national governments, media organizations, civil society, education ministries and funding bodies.

In the nine months since February, the debate about mis- and dis-information has intensified, but, as our report argues, we’re still failing to appreciate the complexity of the phenomenon at hand—in terms of its global scale, the nuances between behavior on different communication platforms (both closed and open) and the fact that information consumption is not rational, but driven by powerful emotional forces.

Unsurprisingly, the report refrains from using the term ‘fake news’ and urges journalists, academics and policy-makers to do the same. This is for two reasons. First, the term is woefully inadequate to describe the complexities of information disorder. Second, it has been appropriated by politicians worldwide to describe news organizations whose coverage they find disagreeable, and, in this way, has become a mechanism by which the powerful clamp down upon, restrict, undermine and circumvent the free press.

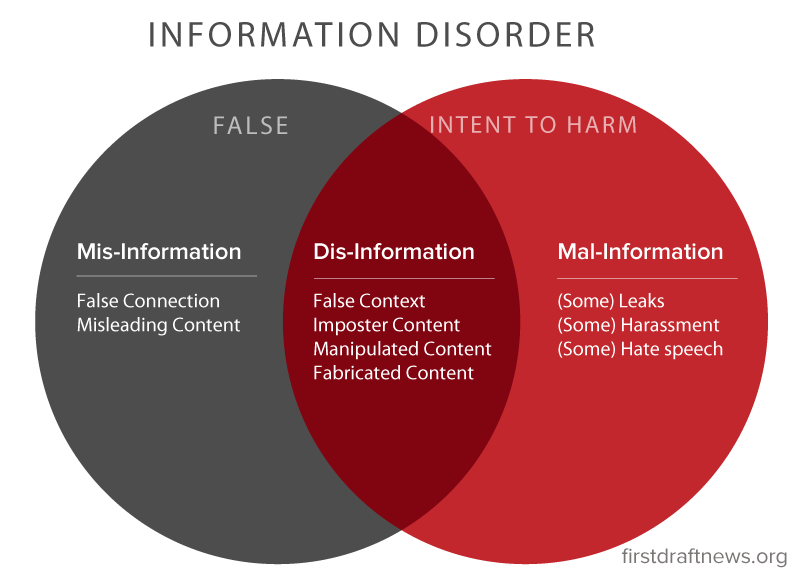

Our new definitional framework introduces three types, elements and phases of information disorder. This is because we can only begin to implement workable solutions after breaking down the phenomenon in this way. We describe the differences between the three types of information using dimensions of harm and falseness:

- Mis-information is when false information is shared, but no harm is meant.

- Dis-information is when false information is knowingly shared to cause harm.

- Mal-information is when genuine information is shared to cause harm, often by moving private information into the public sphere.

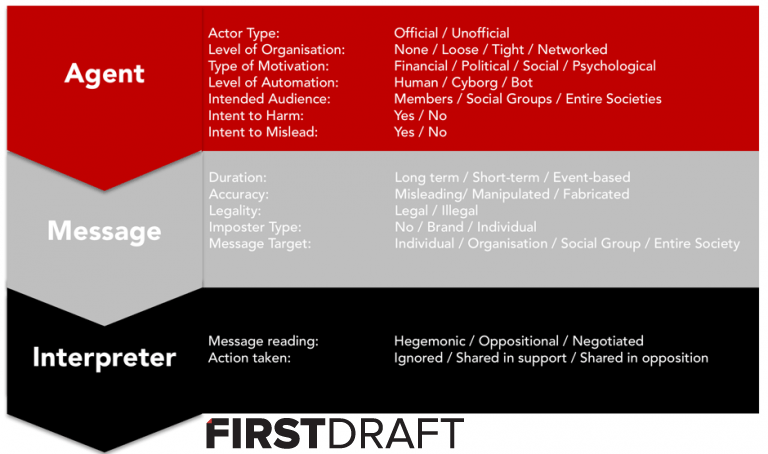

We also recommend thinking about the agents, messages and interpreters of information disorder as separate elements. This is important because even small differences in any of these elements will necessitate significantly different solutions. For example, we argue those who create mis-, dis- or mal-information do so for four main motivations—financial, political, social and psychological. Solutions that target financial motivations requires careful consideration on their own. Lumping together those who are financially motivated by profits with those who seek political gains is unhelpful.

The three elements of information disorder: agent, message and interpreter.

Research on differently formatted messages also call for very separate sets of questions. The debate about misleading and/or harmful messages has been overwhelmingly focused on fabricated text news sites, when visual content is just as widespread and much harder to identify and debunk. Likewise, many assumptions are made about the impact of misleading and fabricated content, but we need much more research to understand how different audiences consume, interpret and respond to these messages. Is this content being re-shared as the original agent intended? Are they being re-shared with an oppositional message attached? Are these rumors traveling online exclusively, or do they move offline into personal conversations that are difficult to capture.

We also argue a need to examine the three phases of information disorder discretely. As we explain, the agent who creates a fabricated message might be different to the agent who produces that message, who might still be different from the agent who distributes the message.

The final key conceptual argument of the report, which draws from the work of the scholar James Carey, is that we need to understand the ritualistic function of communication. Rather than simply thinking about communication as the transmission of information from one person to another, we must recognize that communication plays a fundamental role in representing shared beliefs. It is not just information, but drama — “a portrayal of the contending forces in the world.” The most ‘successful’ of problematic content is that which plays on emotions of contempt, anger or fear. That’s because these factors drive sharing among people who want to connect with their online communities and ‘tribes’. It’s easy to understand why emotional content travels so quickly and widely – even as we see an explosion in fact-checking and debunking organizations – when most social platforms are engineered for people to publicly ‘perform’ through likes, comments or shares.

The three phases of information disorder: creation, (re)production and distribution.

Beyond our conceptual proposals, we provide a round-up of research, reports and practical initiatives connected to the topic of information disorder. We examine solutions that have been rolled out by the social networks, and consider ideas for strengthening existing media, news literacy projects and regulation. Lastly, we discuss future trends—in particular the rise of closed messaging apps and artificial intelligence that manufactures or detects disinformation.

We hope this report will be a resource to academics embarking on research in this area, policy-makers advising regulatory bodies and funders making decisions about where to allocate philanthropic resources. While many people only became aware of the challenges of information disorder after the election of Donald Trump – and the subsequent reporting on fabricated news sites, micro-targeting and dark ‘posts’ – these issues have been building for a long time, and are not caused solely by the technology companies. Rather, we’re seeing the symptoms of a host of global socio-economic shifts. As such, solutions will need to take aim at these deep-rooted causes as well, rather than simply tweaking algorithms or writing regulations.