There are now numerous resources documenting the verification process for eyewitness media and user-generated content. Much of it relies on an assessment of the source and of the content itself. But the creation and consumption of UGC is very much a cultural artefact, and differs by region.

Journalists are a group of people with an interest in UGC for professional reasons but we are consumers of it as well. We know where to look for the things we like, follow the people we know who post interesting things and generally understand the language, humour and styles that the creators and uploaders of this content use.

But back in the newsroom, as geographical boundaries become less of an issue in terms of the news we cover, we cannot just assume that UGC culture is the same everywhere. If we approach all content and creators in the same way then we would be making a big mistake. Understanding this is essential for verification in news. Always put yourself in both the mind and the place of the person witnessing the events and creating the content you are looking at.

So how has the culture of social media and UGC for news developed?

Two different examples of social media and UGC highlight the need to consider culture as much as you would anything else.

In 2016 it would be reasonable for many journalists working with UGC to need to access content from both Syria and the United States, but working with sources and content from these two places are very different experiences.

Syria

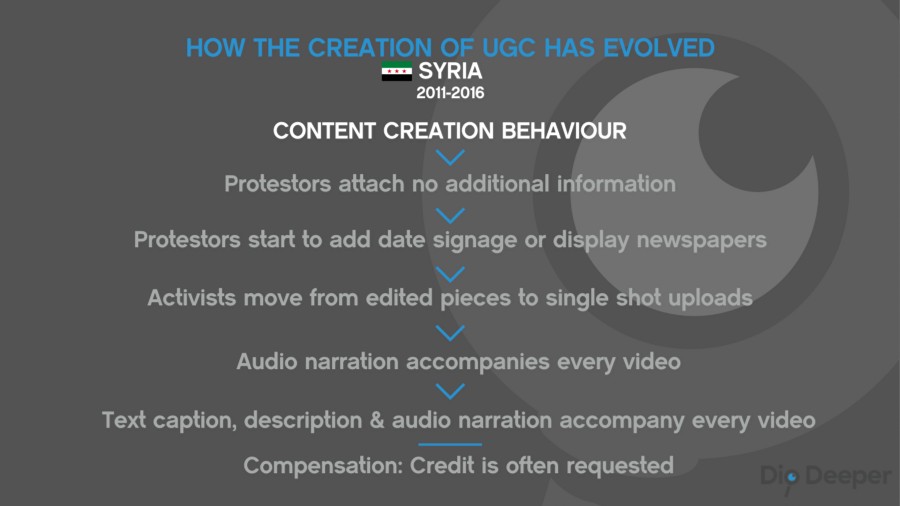

Syrian UGC (from activists and opposition forces) is often accompanied by a large amount of data to aid verification.

Back in 2011, protestors in Syria’s cities came out to protest against the Assad regime, events which followed similar protests seen across the Middle East. Syrian protestors emulated the YouTube videos they had seen from other uprisings: chiefly, shots of protests in the streets and, if possible, examples of the brutality of regime soldiers cracking down on dissent.

However, unlike the other countries in the region where protests started in a similar way, the protracted transition into civil war meant that for a long period UGC was the only way to show what was happening across the country. Individual content creators organised themselves into groups or ‘media centres’ and started to regularly communicate with journalists in the west who were seeking to validate the footage. This process saw the nature of the footage change, because of the unique situation both sides were in.

A video from Homs in March 2011 shows protests but has no accompanying information to help validate the date, location or event

Those first videos showing protests in the street were difficult to verify because contact with the original uploader was slow and little information accompanied the content. As the protesters recognised the value their footage held for news outlets, they also saw what type of video was used and what wasn’t — the more information, the more likely it would make it to air.

A video from Damascus in July 2011 includes the creator showing a handwritten sign to give more information

We then started to see videos with people holding up the front pages of newspapers. This turned into signs being held up detailing specific information about the date, location or the event.

The next iteration took into account that videos were being scraped or edited and information was potentially lost in this process. After all, most non-journalists wanted to see the action, not waste time looking at a handwritten sign.

In 2016 most videos from Syria have an audio narration plus a more detailed caption and description of the events

Today, we have audio narration on most videos out of Syria — these then match captions and descriptions on the YouTube and Facebook channels. The media centres know what journalists need and many have relationships that allow blanket access to material. They also have methods for fairly fast communication.

How the creation of UGC has evolved in Syria from 2011 to 2016. Fergus Bell/Dig Deeper

But these are not regional characteristics of UGC. To expect the same from Egypt, Lebanon or Libya would be wrong, a very specific set of circumstances have led to this UGC ecosystem in Syria. Newsworthy material regularly emerges from these countries on social networks, but to search for and verify it in exactly the same way may be fruitless or – worse – bring back false positives from people trying to mislead journalists.

USA

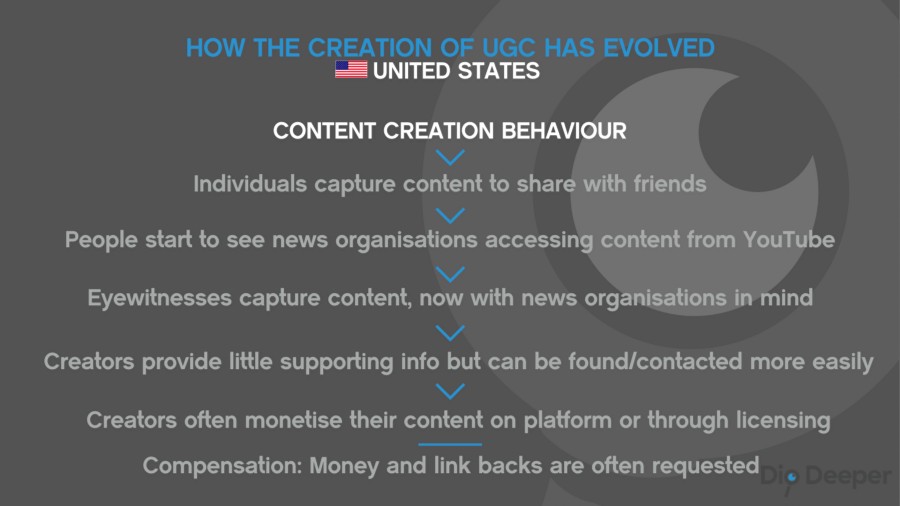

The situation for journalists and the ecosystem for UGC in America is very different.

Unlike Syria, UGC has not been the only way to report on major stories or political movements in the United States. There has been no recent civil war, and Americans see UGC broadcast by news organisations more often than Syrians do.

There hasn’t been a need to provide huge amounts of information about events with the content that is uploaded, either, as it is much easier for news organisations to independently confirm events happening on their doorstep. Content of any value is aggressively pursued by competitors and individuals are easier to trace in the US. They can be found on Facebook or LinkedIn and they are much more likely to have their smartphone in their hand, which makes contact a lot easier.

A typical piece of UGC from a newsworthy event in the United States

In the US, uploaders will frequently give the location and other information in the title of videos uploaded to YouTube – which helps with basic, fast searches. However, little additional information is likely to accompany the material beyond this. The regular lack of a narrator giving the time, date and location of the video, as in Syria, can cause problems with scrapes because no contextual information is carried with the footage when it is uploaded again.

The nature of the content is also different. People often know — or at least believe — that they have something of value. In contrast to Syria where a credit accompanying their content is often enough, American uploaders ask for monetary compensation much more often. This also means people know where to make money and — unlike in most other regions of the world — there is a strong culture of people submitting content to their local, trusted broadcasters or publishers. It might never be posted to a social platform — something that can certainly confuse journalists outside of the region when they are unable to find a video that a local outlet might be running.

How the creation of UGC has evolved in the United States. Fergus Bell/Dig Deeper

Your go-to platform might not be theirs

Just because your personal networks use certain platforms in your own country, doesn’t mean that those same platforms are the go-to place for those in different places. The evolution of social networking in those countries is again important to consider.

In Brazil, Orkut used to be the primary social network before Facebook took over. In Syria, people live-streamed UGC using Bambuser, long before Facebook and Twitter introduced their own versions. As live-streaming became too unsafe it eventually tailed off. YouTube still dominates as a platform for Syrian activists but they replicate a lot of their work on Twitter and Facebook as well.

Although the number of platforms people are posting to seem to be narrowing, the way various cultures got to that point and the way it looks now present both unique and new challenges.

Malachy Browne, managing editor at Reported.ly and fellow First Drafter, has spent a lot of time working on UGC from Yemen.

“It used to be all YouTube in the early day,” he told me. “Now UGC can reach you through a number of platforms. Including from private groups and closed networks, so it’s harder to trace the originator.”

In contrast, Eliot Higgins, founder of Bellingcat and another member of First Draft, describes where UGC is most prevalent in Russia and Ukraine:

“VK.com and Instagram are the main sites, plus Odnoklassniki for the slightly older generation. We find there’s a lot of active communities on there based around specific groups/activities or locations.”

To have a definitive list of who posts where would be useful but is never going to happen. People in war zones will post to the easiest place based on their connectivity and the visibility it will give their message. In the West, people will post to the most popular network of the time. There will never be consistency and as digital newsgatherers it is our job to understand the evolution of platforms and UGC culture as much as it is to be up to date on verification techniques.