In 2017, First Draft initiated a collaborative journalism project around the French presidential campaign, gathering 37 newsrooms, technology and academic partners from France, Britain and Belgium. The Brexit referendum and US Presidential elections in 2016 had fostered a feeling of emergency among news organisations as disinformation spread across social media. There was a conscious need to address the trust and transparency issues between media and their audiences.

More than 100 journalists across 33 newsrooms monitored the social web together. They reported collaboratively on 63 pieces of ‘problematic’ content. Following Claire Wardle’s seven types of mis- and disinformation, journalists avoided the overly simplistic and often misleading “true” and “false” labels. The hope was to better understand the tools and techniques employed by hoaxers and propagandists and report them to the audiences more effectively.

In November 2019, First Draft set up a monitoring operation to investigate the French online information space once again. This new phase, leading up to the municipal elections in March 2020, shows how fast this age of information disorder is evolving and becoming more complex. Indeed, the need to better prepare and join forces to tackle it is clearer than ever.

Inevitably, some notable features of this information environment have persisted. Online political disinformation often aims to bolster a small number of recurring narratives, with many of these revolving around anti-immigration sentiment and the perception of social unrest.

Old pictures and videos are still often shared as ‘evidence’ to further these narratives and provoke strong emotional responses. Recent posts include an outdated picture of a police confrontation and a video from Iran presented as French anti-riot police. These mirror instances of misinformation uncovered in 2017, when a refugee crisis in Turkey, as well as misattributed pictures and maps falsely accusing immigrants of crimes, were all used to promote narratives of social unrest, government repression and uncontrolled immigration.

A photo taken in 2010, re-published in September 2019 with text “The scandalous picture policeman versus fireman who save lives”. Screenshot by author

Many of the sources which pushed problematic content in 2017 have remained active and these websites and well-followed social media accounts continue to influence receptive online communities. Their success in maintaining their role among the so-called ‘patriosphère’ (the ‘patriots’ sphere) or even ‘fachosphère’ (the ‘fascists’ sphere) comes in spite of major news sources detailing the extent of their deception.

However, in under three years, these tactics have evolved. Here are five examples of some of the most significant developments we have identified during our latest monitoring project.

More false context than fabrication

Fabricated or poorly manipulated content constituted a small but noteworthy part of the claims that were verified through CrossCheck in 2017. Unfounded rumours aimed at undermining the credibility of political candidates, fabricated polling results taken from imposter accounts and poorly doctored photos used to generate newsworthy headlines are all examples of manufactured content that occasionally surfaced in the run up to the presidential election.

During the more recent monitoring period in late 2019, few instances of fabricated content arose. Most failed to generate any significant engagement. The majority of well-performing pieces of misinformation relied on subtle conjecture and misrepresentation. Recent examples include shortened quotes designed to amplify the polarising effects of controversial public figures or outdated opinion polls which undermine politicians.

False context is now being used more strategically to generate the most traction online. In the last months of 2019, two notable examples stood out where outdated and incomplete information was circulated at specific times chosen to capitalise on tensions and maximise deceit.

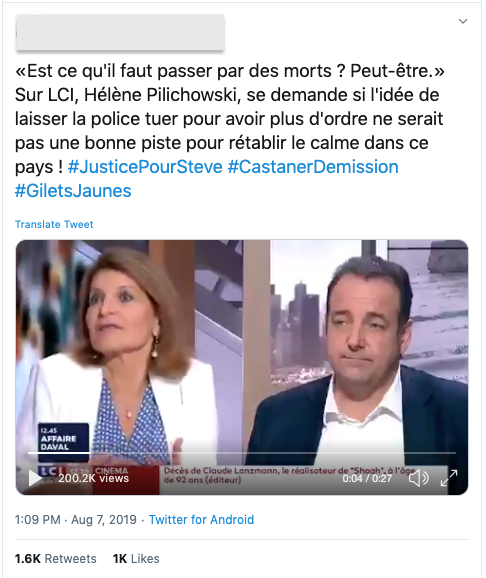

In a 2018 television news show, a journalist at national broadcaster LCI had suggested that there may “have to be a death” in order to restore relations between protestors and the police. This highly controversial quote was re-published on Twitter a year later but, crucially, just a few days after the discovery of the body of a young man whose disappearance had been linked to a violent police intervention at a music event.

The post contained hashtags related to the case and did not include any indication of the original date of the interview, leading many online users to believe the comments were made in relation to the case. Several unreliable news websites as well as international media outlets then published articles that used the quote as a headline and omitted any indication of the original date. These were also widely shared on social media. The timing of these posts further polarised the contentious debates around police violence and media bias in France.

This clip from 2018 is posted on Twitter with hashtags ‘justice for Steve’, ‘Castaner Resign Now’, ‘Yellow Vests’.This clip from 2018 is posted on Twitter with hashtags ‘justice for Steve’, ‘Castaner Resign Now’, ‘Yellow Vests’. Screenshot by author.

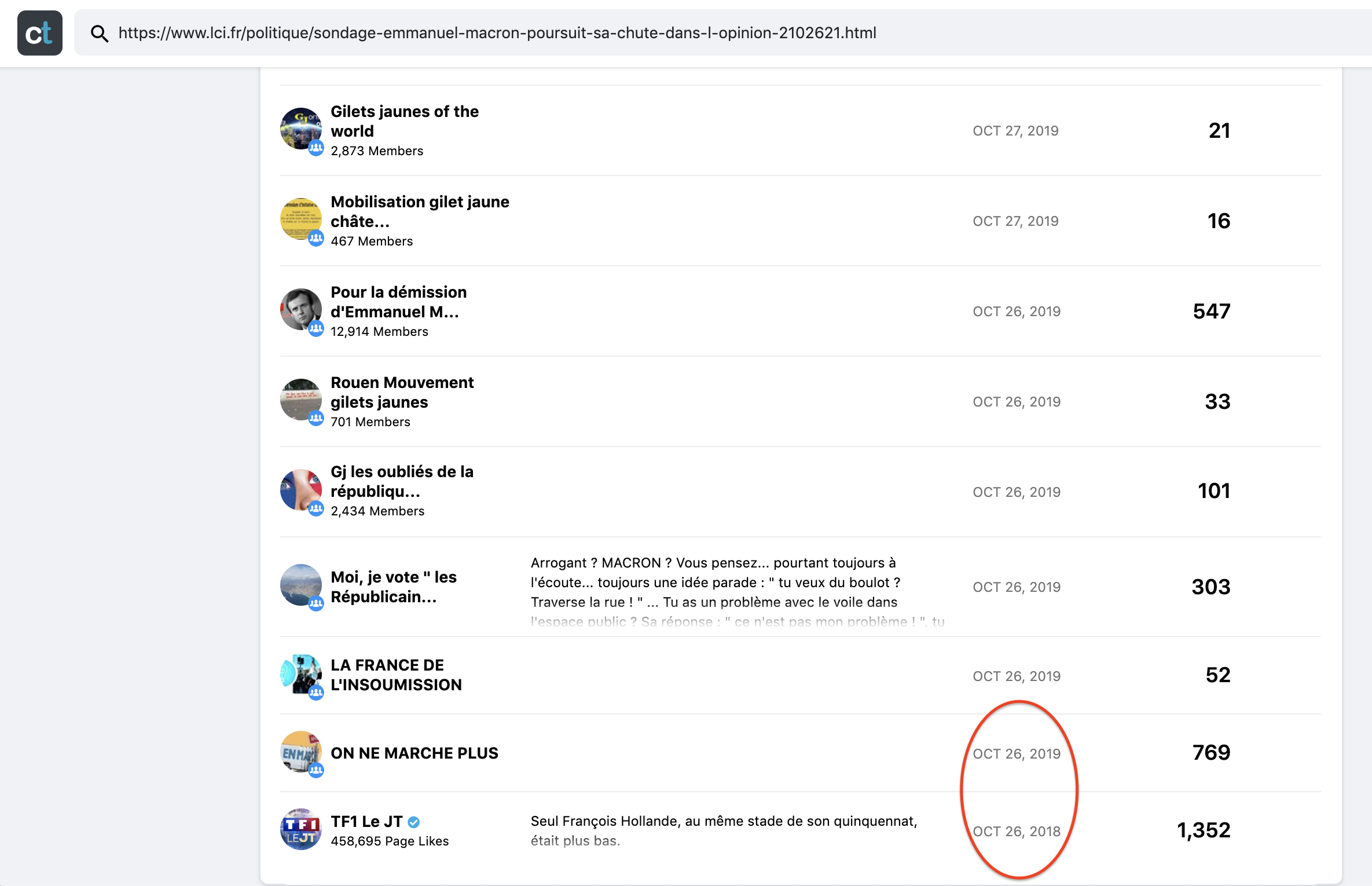

Similarly, an opinion poll published on October 26, 2018 revealed Macron’s approval rating had fallen to its lowest level since his inauguration. On that day, LCI reported the poll in an article titled “Opinion Poll: considered ‘arrogant’, Macron’s approval ratings continue to drop’”. This article, whose thumbnail does not feature any indication of its publication date when shared as a social media post, was then re-posted on six Facebook groups exactly one year later, on October 26, 2019.

CrowdTangle’s LinkSearch function used to track URL links shared across social media platforms. Screenshot by author.

Posts that contained outdated links to the poll were published on dozens of Facebook groups with over 350,000 combined members and went on to amass over 8,000 interactions over the following month.

Content ‘recycling’ and coordinated link sharing

Several misleading or inaccurate articles reported on Crosscheck in 2017 had been spread by a number of untrustworthy news websites.

Misattributed polling results, unfounded claims of political censorship and misleading reports implying the erosion of French culture had all been amplified by a number of similarly unreliable online sources. Connections between these online sources are often explicit: ‘recommended links’ and ‘partner logos’ appear at the bottom of many of their websites. Claims identified in 2019 suggests these networks recycle content more frequently and have become less reliant on organic content.

In all three of the cases mentioned above, each website had produced its own original material around the story. In the 2019 monitoring project, most misinformation found in the form of online articles had been amplified by numerous websites and, in many cases, simply copied or shortened from one website to the other. In one example, a shortened quote taken out of context from an article co-authored by Greta Thunberg was the subject of three different article versions, with identical copies of each used by at least three separate websites.

Multiple websites publishing identical stories using a shortened quote as a headline. Screenshots by author.

Such content ‘recycling’ can amplify misinformation by maximising its reach while the multiplicity of reports around a single issue can help create an illusion of newsworthiness and, by extension, credibility.

In addition, certain disinformation networks are now disseminating content in a more coordinated manner on major social networks. The 2019 project identified article links from a group of new ‘re-information’ websites that were spread across Facebook Pages and Groups within minutes. Articles from these sources, including debunked, manipulated quotes or repurposed satirical content were published on as many as half a dozen pages and groups in under four minutes. A joint investigation from Le Monde and the EU Disinfo Lab found theses websites to be part of a foreign network of inauthentic sources.

A false claim suggesting government secretary Mrs Schiappa wanted to ban the broadcast of church service ceremonies on television. Screenshot by author.

These tactics have also recently been observed in other online spheres. Researchers at the University of Urbino found numerous networks of Facebook Groups, Pages and public profiles had spread links in a coordinated manner during the 2018 Italian general election and the 2019 European elections in Italy.

Such tactics could proliferate in upcoming election cycles as the study found that, on average, links shared in a coordinated manner generated more interactions.

Weaponisation of satirical content

In 2017, five pieces of satire had been verified through CrossCheck after a number of users had taken the content seriously. The satirical nature of the sources was often easy to spot, either thanks to their name, such as Le Gorafi’s play on Le Figaro, or the type of content hosted on their website. In one case, a prank site was used to fabricate a controversial policy proposal ‘put forward’ by then-candidate Emmanuel Macron.

Satire continues to play a major role in online political conversation, and it plays an important role in society when everyone is in on the joke. However, it seems online satirical content is being weaponised in a more concerted and targeted manner than in the examples found in the 2017 CrossCheck project.

A satirical website created in April 2019 that mimics France TV’s name and logo saw two of its articles go viral, with one generating just under half a million interactions on Facebook. The articles’ deceptive appearance and subtle humour (a fabricated but credible ‘quote’ from President Macron) were used to further polarise debate over Macron’s presidency.

Users spread these links on numerous Facebook Groups with emotive captions that suggested the quote was authentic. Certain posts containing identical captions were shared in spurts. Some reached as many as four groups within 16 seconds, according to CrowdTangle data. One website (found to be part of an inauthentic network of news sources mentioned above) copied the satirical article and published it alongside its other, non-satirical articles. This link was then spread on five public Facebook Pages and Groups in less than four minutes before circulating on many others later that day.

Satire was also used to target and discredit individual politicians. One parody Twitter account joked that government spokesperson Sibeth N’Diaye supported a high-profile politician who had recently been found guilty of fraudulent activity by posting a fabricated quote.

The tweet was screenshotted and cropped to mask the satirical nature of the source and this manipulated visual was widely shared on Facebook through posts with inflammatory captions.

Similarly, another fabricated quote from satirical website ‘desourcesure’ mocking Mrs N’Diaye was used to create a meme that went on to be widely shared on social media. The meme included the words ‘who voted for that?’, in an apparent attempt to provoke an emotional response. In both cases, many users reacted with ‘angry’ emoticons and media organisations published related fact-checks.

Photo containing a fabricated satirical quote but cropped to hide satirical nature of the source. It is accompanied by the caption “Please someone make her shut up!!”. Screenshot by author.

The use of fabricated quotes on images to target people of colour in public office mirrors developments in the run up to the UK general election in 2019 where similar tactics were employed to undermine candidates.

Such memes and images overlaid with text have become an increasingly common vehicle for misinformation and present unique challenges for online audiences and reporters alike.

Memes and text on images

With the exception of this article link that featured an image as a thumbnail, no misleading or inaccurate text on images were reported on through CrossCheck in 2017. In contrast, few days would pass during the 2019 monitoring project without misleading memes or images with text being widely shared online.

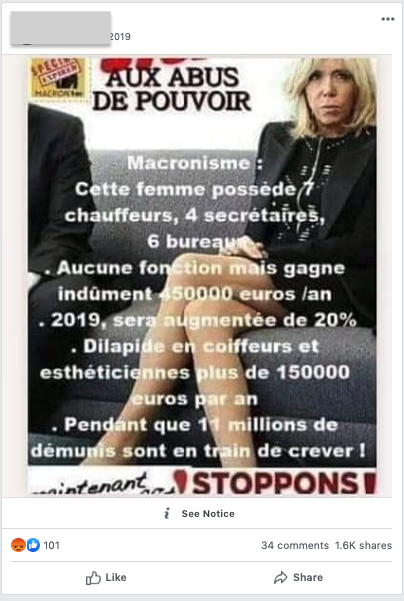

Images that include fabricated quotes, exaggerated statistics and inflammatory language have shown the ability to provoke strong emotional responses and further entrench individuals’ beliefs over these last months. These types of content, which were also a key feature of online misinformation during the UK general election last year, are notoriously quick and easy to make but difficult to track and report on.

Inaccurate and misleading statistics superposed on a picture on Brigitte Macron. Screenshot by author.

Tools and techniques which rely on text to monitor the social web are mostly ineffective as these pictures are often shared without captions. Furthermore, tools that help track the circulation of online content struggle to capture accurate data for manipulated or edited images.

One solution is the Project Naptha browser extension, which can help extract text from an image. The text can then be used to try and identify whether similar information had been shared elsewhere but results tend to be scarce.

Research has found that statements are more likely to be believed when presented using images. As these become an increasingly common tool for spreading disinformation, it is more vital than ever to consider a sources’ motivation for using imagery when advancing a political opinion.

Alternative Platforms

‘Mainstream’ social media platforms, most notably Facebook and Twitter, are still home to the overwhelming majority of online political discussion in France. Therefore, these spaces remain the key battlegrounds for agents of disinformation. Since 2017, these platforms have played a more active role in responding to the spread of online disinformation. Measures such as stricter content and account moderation policies and third-party fact-checking partnerships have made these platforms more hostile to disinformation agents. Reports of large scale takedowns of inauthentic accounts have become an almost weekly occurrence.

Over the last three years, many influencers and disinformation websites within French online communities have sought to encourage the spread of their content through alternative, largely uncensored platforms. In several cases they have created their own accounts through which to disseminate their content on these channels. Some sources are now operating exclusively through these channels after being banned from mainstream platforms altogether.

More specifically, VKontakte (commonly known as VK) and direct messaging app Telegram are increasingly used by French online sources and communities who often cite concerns of content censorship. VK has grown to host dozens of French speaking groups with some containing several thousand members.

Telegram counts similar numbers of French public ‘information’ channels although their subscriber numbers tend to be more limited, often remaining at under a thousand. Links to VK and Telegram accounts and ‘share’ buttons can now often be found on popular French disinformation websites. The same were often limited to Facebook, Twitter and YouTube in 2017.

While we found little evidence of exclusive content shared by disinformation-peddling sources on these platforms, several instances of misinformation on Facebook were also circulating on VK public groups and Telegram channels.

In October 2019, the Rassemblement National announced the launch of its own Telegram channel, suggesting that unreliable online sources of information are not alone in recognising the potential of this communication medium.

Rassemblement National candidate Jordan Bardella invites users to follow the party’s new Telegram channel. Screenshot by author.

This trend is by no means restricted to France. Platforms such as Gab, Bitchute and Brighteon are continuing to attract communities that share content considered to advance more ‘extreme’ views. These platforms’ features bring serious considerations around security and ethics for journalists and researchers reporting on political disinformation. However, as the importance of these platforms grows, so does the need to understand how these digital spheres function and how they may affect the wider information ecosystem.

With the first round of the municipal elections fast approaching and an ongoing climate of emotionally charged and partisan material on social media, online disinformation has the potential to play an even more important role in political debate. As tactics used to push misleading content continue to evolve, voters must remain vigilant when navigating the social web.

Marie Bohner also contributed to this report.

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by subscribing to our newsletter and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.