As tensions between Ukraine and Russia continue to simmer, the need for journalists to delve into the Russian-language internet, or RuNet, and verify reports is coming back to the fore. But investigating sources, images and stories originating in Russia and Eastern Europe can be challenging if you don’t know the language.

The differences in conducting research into Russian sources are not just in the language itself, but also the toolset, as there are often superior alternatives to services such as Google Maps and Facebook for searching the RuNet.

In addition to providing a resource for non-Russian speakers on navigating an unfamiliar section of the internet, this guide shows there are special challenges in finding and verifying materials for stories in different languages and regions. Most of these guidelines are equally applicable for when you are researching in Turkish, Arabic, or any other language with an active online user base.

Expand your toolbox

Most journalists have a handful of online tools they use for research and verification, such as Google Maps for checking locations, and Facebook and Twitter for finding stories and people. These tools still work quite well for stories in most countries due to their near-ubiquitous reach, but there are often superior alternatives.

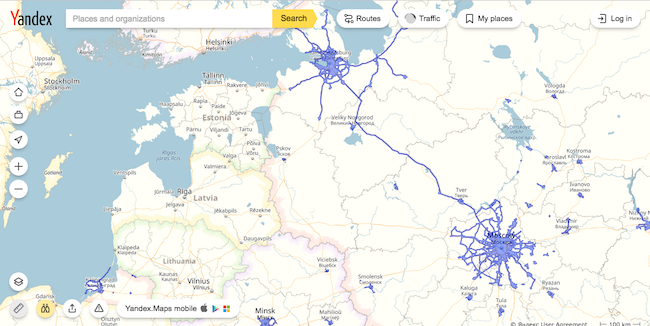

The Russian equivalent to Google is Yandex, which provides a search engine, news aggregator, image search, and a mapping service, among other features. While the search function is nothing to write home about, Yandex Maps is an excellent service that often trumps Google Maps in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. By selecting the binoculars in the bottom-left of the screen, you can turn on the “Panorama” view – Yandex’s answer to Google Street View.

The blue areas on the map show the available street-level imagery for Yandex Panorama

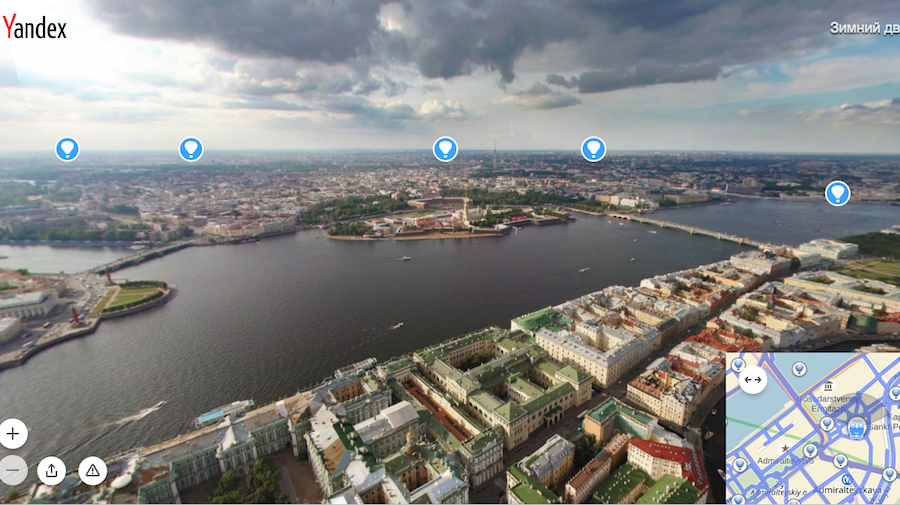

Yandex has taken numerous ultra-high-resolution photographs from balloons in some major cities, allowing a perspective in between a ground-level view of the street and satellite image.

St. Petersburg, as seen from an overhead balloon. Each blue balloon icon indicates additional available imagery from this perspective

Search smart

Just as when searching for materials for a story in English, the most common search phrases you will plug into Twitter, Instagram, and other websites are place names. If you are looking for information for a fire or shooting at a club, it makes sense to search the club’s name, street address, and city in Twitter to find witness accounts, photographs, videos, and so on. This practice will obviously work in most other languages, but some services can handle these searches better than others.

In Russian, as with other languages, adjectives and nouns that make up place names do not stay static, as they do in English. When describing something happening at the Bolshoy Theatre, the word “Bolshoy” never changes in English, but just as “he” can change to “him,” the word “Bolshoy” will change its ending in Russian depending on its role in the sentence.

If you are looking for witness accounts on Twitter, searching for the word “Bolshoy” in Russian will not show you someone talking about something at the “Bolshom” Theatre, near the “Bolshogo” Theatre, behind the “Bolshim” Theatre, and so on. Unlike Twitter, this problem does not present itself when using Google searches, as it recognises the changing forms of words in Russian and other languages, and will include them all in your searches.

If you are coming up short in finding materials in almost any language on Twitter, try plugging a keyword into Wiktionary.org and then copy/pasting the variations of the keyword from the “Declension” (for nouns and adjectives) or “Conjugation” (for verbs) section. This method gives you over a dozen forms of the word “Bolshoy” to expand your search.

Declension table of all possible forms of the word “bolshoy,” providing keywords to use in search algorithms

Search in the right place

Even with the perfect search keywords, all is for naught if you are not searching in the right places. The vast majority of Russians do not use Twitter, and only about 10 million have a Facebook account – but over 60 million have accounts on the Russian Facebook clone Vkontakte (VK).

The service is also extremely popular in the rest of eastern Europe, central Asia, and the Caucasus. As detailed in a guide on Russian social networks, it is quite easy to search on VK without using much Russian, and its search features when tracking down specific groups of people are far more powerful than those of Facebook.

Home page for Vkontakte, or VK, the most popular social network in eastern Europe and parts of central Asia and the Caucasus

A phenomenon on VK that does not exist with most countries in western Europe and the Americas is the popularity of local groups to spread and verify information. Often the best way to find and verify materials in eastern Europe is to track down the town or area’s group page, which can have thousands of participants. If there is a wildfire in a remote Siberian area or plane crash in Ukraine, the fastest way to find photographs, videos, and witness accounts will be to visit these local group pages.

VK is also different from Facebook and other Western networks in the abundance of military service information available, often in the form of public groups for different military units. Searching for these groups is relatively simple, and you can search for users with certain kinds of military service, employment or education, both past and present.

As with all social investigations, there will be useful sources who do not have social network accounts, and the information given by some sources on social media may not be true. It is also worth looking into other networks like Odnoklassniki, which has 40 million Russian users, and Moi Mir (25 million) to cast a wider net.

Find out more details about these networks and others in the full version of this guide over at Global Voices.

While this summary was specific to Russian-language resources, the same lessons can be applied to nearly every region for finding news and verifying materials. For example, with Chinese sources, you need to find your way around Weibo, and public Telegram groups are the often best way to find new materials related to Syria. The tools and practices journalists use for stories in the United States, UK, Germany and France, for example, will work reasonably well for other countries, but to find the most relevant and newsworthy materials, a “one size fits all” approach has to be replaced with a regionally focused one.