This is the second part of an ongoing First Draft series on online narratives about China’s vaccines. Read the first part, about misinformation targeting the Chinese-made vaccines, here.

Similar to its history as a Chinese city with a colonial past, Hong Kong has Covid-19 vaccine options from the East and West: CoronaVac, by Chinese pharmaceutical company Sinovac; and Comirnaty, co-developed by Pfizer in the US and German drug manufacturer BioNTech. Despite free vaccination and an abundance of supply, only around 14 percent of the city’s 7.5 million people have received at least one dose as of May 11.

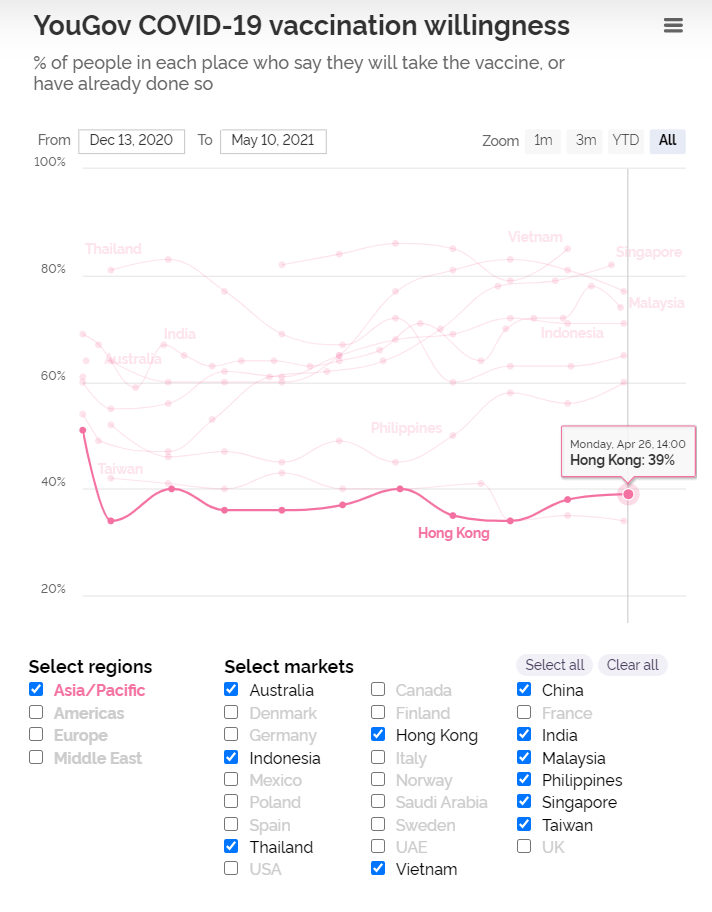

According to Britain’s YouGov poll, the percentage of people in Hong Kong who said they would take the vaccine or had already done so between December 13 and May 10 is among the lowest — around 39 percent — compared with other countries in the APAC region.

May 14 screenshot of YouGov stats on Covid-19 vaccination willingness in the APAC region between December 13 and May 10

The reluctance to get vaccinated is somewhat peculiar in a city well-versed in prevention and control measures against epidemics, and where people generally adhere to them. Following the SARS outbreak in 2003, Hong Kongers have been diligent in keeping up the habits of mask-wearing and disinfection. Having tracked online sentiment about the vaccines in Hong Kong since the beginning of the city’s rollout in late February, First Draft’s research found that there are several dominant online narratives that, given Hong Kong’s previous adoption of critical public health measures, might explain this unexpected hesitancy.

Our research found that apart from general concerns about the safety and efficacy of the vaccines, the skepticism apparently stems from a deep distrust in authorities — both the Hong Kong and Chinese governments. Covid-19 and the vaccines against it came after year-long pro-democracy protests in 2019 and a sweeping national security law that China imposed on the city the following year. A lack of confidence in the government to act in the people’s interest during that turmoil was reflected in online discourse about the vaccines — most of the misinformation and concerns in Hong Kong focus on the Chinese-made Sinovac shot.

The most prominent vaccine misinformation in Hong Kong includes misleading claims about the safety of the Sinovac vaccine as well as unfounded claims that the Hong Kong government may be pushing the Sinovac shot for political reasons. These examples demonstrate that apprehension about the vaccines is as much a sociological phenomenon and an emotional response as it is a lack of understanding scientific facts. Only by dissecting the most common types of misinformation and understanding the root concerns can authorities in Hong Kong improve their public health messaging and, eventually, the city’s vaccination uptake.

Distrust in authorities

False claims such as “Carrie Lam did not get the Sinovac shot!” came immediately after the Hong Kong leader and her administration were vaccinated at a public event February 22. A narrative that they were not given the Sinovac shot as announced and were in fact given the BioNTech or AstraZeneca vaccine quickly circulated on platforms such as Facebook, Telegram and Reddit-style forum LIHKG. The Hong Kong government dismissed the claim as “unproven rumors” in a Facebook post, adding that Lam had indeed gotten the Sinovac vaccine and that BioNTech’s had yet to arrive in the city. This narrative questioned the integrity of Lam’s administration and highlighted unease over reports that the Sinovac vaccine might be less effective. Results from clinical trials also showed the BioNTech vaccine had 91.3 percent efficacy against Covid-19, while Sinovac was 67 percent effective in preventing symptomatic infection.

February 22 screenshot of a Facebook post published the same day in a public group with nearly 130,000 members

Media amplification

As more people got vaccinated in Hong Kong in the past month, adverse reactions caught the attention of many social media users and local news organizations, as well as Chinese state media. “Victim of the syringe — another post-Sinovac death”; “the 12th death / Sinovac vaccine” — these are just a few examples of social media posts from local news organizations featuring headlines that focused on deaths or injuries without providing context. They were often among the public vaccine-related posts with the highest engagement in Hong Kong between February and May, according to CrowdTangle data.

To put things in perspective, this May 2 press release from the Hong Kong government provided an update on some of the post-vaccination adverse events: “A total of 14 death reports (0.001 percent of all doses administered) with vaccination history within 14 days were received in the same period and none of them had clinical evidence to support the events were caused by the vaccines.” Investigation into a cause of death may take time and while the media’s responsibility is to inform the public, rushing to report on adverse reactions without knowing about a person’s underlying medical conditions or other circumstances could risk amplifying misleading information about the vaccines.

Incomprehensive or inaccurate reports on adverse events could contribute to a low vaccination rate, which seems to align with the reality of Hong Kong at the moment. That’s why it is important for publishers to consider the “tipping point” — where the mere act of reporting always carries the risk of amplification and newsrooms must balance the public interest in the story against the possible consequences of coverage.

Hesitancy toward Sinovac vaccine

Fears over potential adverse reactions among Hong Kongers also centered on the Sinovac vaccine. For instance, a video circulating on LIHKG, Facebook and YouTube in March shows a man purportedly having a seizure after getting the shot. The footage had been viewed tens of thousands of times on YouTube since being uploaded March 21. An identical clip was at No.15 in the top trending posts on LIHKG on March 22 — the forum has estimated monthly traffic of over 3 million people. Some comments on the LIHKG post said the man would have received the Sinovac vaccine, that the vaccines were “problematic” and people who got it were “sentenced to death.” However, a reverse image search on Google found the location of the video identical to one of the venues used for the administration of the BioNTech vaccine.

Screenshot comparison by First Draft of a scene in the video (left) and a government image of Yuen Long Sports Centre, one of the venues for administration of the BioNTech vaccine

Conversely, negative reaction and misinformation about the BioNTech shot have been relatively muted among Hong Kong-based social media users, even following the vaccine’s temporary suspension in late March because of packaging defects in one batch. This means skepticism toward the Sinovac vaccine could have been compounded by misleading narratives and negatively framed headlines, as well as a lack of transparency over data on its efficacy and safety.

Analysis

A theme that runs parallel to mis- and disinformation about the Sinovac vaccine is a distrust in authorities. The Covid-19 pandemic came as months of pro-democracy protests in 2019 in Hong Kong slowly wound down, but tensions between China and Hong Kong continued. Critics say Beijing has been tightening its grip on Hong Kong ever since by way of a national security law that some say aims to stamp out opposition to the Chinese Communist Party; an electoral system reform that stipulates only “patriots” can rule Hong Kong; a wave of arrests and prosecutions of pro-democracy figures; as well as a proposed “fake news” law meant to tackle “misinformation, hatred and lies” but which journalists fear will erode press freedoms and strengthen Beijing’s control over the Chinese territory.

Political leaning notwithstanding, general instability and perceived loss of freedom, including that of the press, brew discontent in Hong Kong, which in some cases extends to Covid-19 vaccines. Confidence in the Sinovac vaccine was perhaps also compromised by food safety incidents in China in past decades, such as the 2004 scandal when human hair was used to produce soy sauce, and in 2008 when lethal milk powder killed at least six babies in China.

Hong Kong leader Lam had said “a small group of people distort the intention of the community testing program and smear Chinese-made vaccines.” She added that there was “malicious spreading of rumors, people stigmatizing and politicizing the vaccine procurement.” What Lam might not have realized is that misinformation often taps into people’s emotions, especially when they are already troubled about vaccines and political uncertainty. Vaccine skepticism does not stay in a bubble, but rather interacts with and plays into existing issues.

Vaccine hesitancy in Hong Kong is a classic case of a feedback loop formed by scientific, emotional and political concerns: People are reluctant to get vaccinated because they are worried about the safety and efficacy of the vaccines and the government’s agenda, and the fewer the people getting vaccinated, the more skeptical the public becomes about the government and the vaccines it provides. Compounded by headlines that focus on adverse reactions and side effects, often without important context, even fewer people will be willing to be vaccinated.

Recent incentives from the Hong Kong government, such as fewer social restrictions for vaccinated people and an expansion of the vaccination program to those 16 and older, saw vaccine bookings double. However, success may be short-lived when vaccination is tied to privileges. Also, other parts of the government’s plan to encourage vaccinations are considered confusing and even discriminatory, such as a now-scrapped plan to make the vaccine mandatory for the city’s 370,000 foreign domestic helpers.

As this review demonstrates, people’s attitudes to Covid-19 vaccines are shaped by factors far beyond science, spanning history, identity and politics. If Hong Kong authorities are to achieve their goal of vaccinating 70 percent of the population by the end of 2021, they must address the deeply rooted distrust in government that is fueling vaccine misinformation and hesitancy.