Co-authored by Meg Kanofski, student of Bachelor of Communications (Journalism) and Bachelor of Arts (International Studies) at UTS Sydney

It took less than a week. Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison called a federal election on 10 April. By the following weekend, a scare campaign claiming that the opposition would introduce a “40 percent death tax” had begun on social media. And the claim stuck.

Google Trends showed a spike in the searches such as ‘death tax labor’ in the lead up to the May 18 election – reaching 100 on the trends index for the state of Queensland.

The prospect of inheritance taxes is politically toxic in Australia. The country stopped taxing people’s estates after they die in the 1970s. None of the major political parties support its reintroduction.

Despite this, the scare campaign took off, describing the tax in more ominous terms as a “death tax”. From Easter, through to Mother’s Day, and right up until polling day on May 18, the claim circulated widely on Facebook, and to a lesser extent on Twitter.

How did this happen?

The claim was repeated by mainstream politicians from the ruling Liberal party, as well as hyper-partisan groups such as the nationalist party One Nation. They took a kernel of truth and adapted it for their purposes. Or to use a musical metaphor, they found a theme and made their own variations.

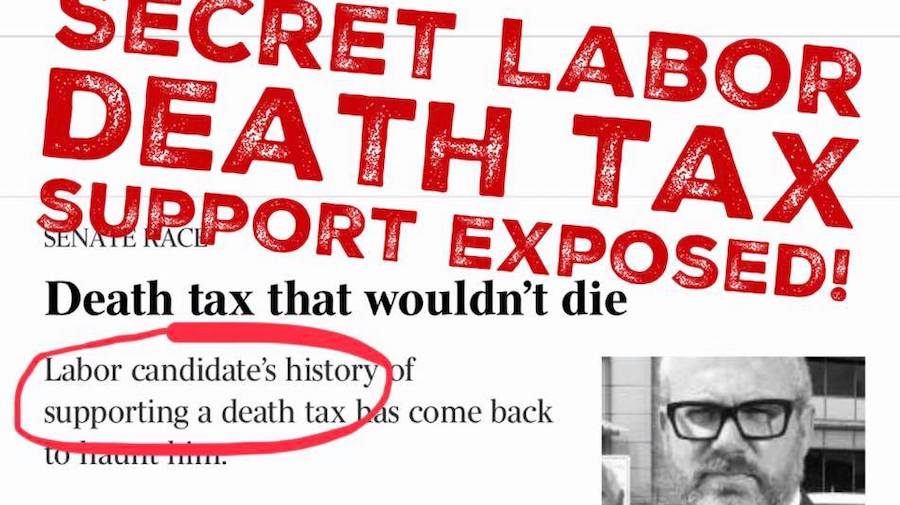

There was a kernel of truth. The social media posts often linked to a January 2019 press release from Australia’s Treasurer, Liberal Party deputy leader Josh Frydenburg, titled: “Death taxes – you don’t say, Bill!”, referring to opposition Labor leader Bill Shorten.

“Facing growing pressure over Labor’s disastrous housing and retirees taxes, Bill Shorten today sought to deflect attention by flippantly remarking that the next thing they will say will be ‘that Labor wants to introduce death taxes,’” Frydenburg wrote.

The release also cited Labor’s Andrew Leigh, the Shadow Assistant Treasurer and a former professor of economics, and his 2006 paper on the merits of an inheritance tax, with the focus on “super rich.”

Some social media users were sent the message from complete strangers.

In the paper, Leigh writes, “we recognise that it is received political wisdom that inheritance taxes can also be spelt p-o-l-i-t-i-c-a-l s-u-i-c-i-d-e. But since we are the only developed nation not taxing inheritances, it is time to challenge this received wisdom.”

It is not uncommon for economists to recommend inheritance taxes. Nowhere in Leigh’s paper does he mention the 40 per cent figure used in the press release and picked up in social media posts. And Labor categorically denied it intends to introduce inheritance taxes.

Yet the claim about death taxes spread widely across social media: early on through Facebook messenger where individuals copied and pasted warnings about Labor’s plans to their Facebook page, or adjusted the theme into their own words.

Supporters of the Liberal Party in Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s electorate were among the earliest known posters on the topic on 17 April. Over the following Easter weekend, the messages gained traction across state borders, and took off in right-leaning Queensland.

The posts were like chain letters, including directions to share the message“with all your friends.” While some altered the wording of the message sent to them before posting, most copied the claim word-for-word. Private Facebook messages provided to First Draft showed that some social media users were sent the message, with instructions to copy and paste, from complete strangers.

One person who shared the post told First Draft she did not know whether the information was “fake news” or not, but was concerned nonetheless and felt compelled to share the post with hundreds of online friends.

Labor requested Facebook remove the posts, warning in a letter that there “seems to be an orchestrated message forwarding campaign about the issue.”

Many of the people posting the messages shared common digital footprints.

Facebook Australia told First Draft that the original post was fact checked by third-party fact-checkers and was rated as ‘False’. “Based on this rating, people who shared the post were notified that it had been fact-checked and rated as false. As a result, the original post and thousands of similar posts received reduced distribution in News Feed,” a Facebook Australia spokesperson said.

Many of the people posting the messages shared common digital footprints. For example, many of the posters First Draft reviewed follow the Facebook pages of the Australian Conservatives, the Liberal Party of Australia, or the Australian Christian Lobby. People posting the message in Queensland also frequently liked the Facebook page of Pauline Hanson, the leader of the populist right-wing One Nation party.

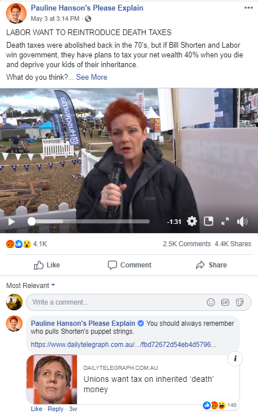

Hanson, who regularly courts controversy with her views on immigration and climate change, went all in on the death taxes scare. Her party was embroiled in scandal weeks before the election after Al Jazeera filmed a candidate from her party groping women in a strip club. Days later, Hanson released a highly produced video claiming Labor would introduce death taxes.

Hanson’s social media strategy is turbo-charged. Her Facebook page shares regular updates and well-choreographed videos and has over 270,000 followers. For example on 7 May, Hanson’s page posted a video about a letter of support from a 12 year old girl that Hanson received while in prison in 2003. The video showed a surprise meeting Hanson had set up with the young woman, to show her appreciation. It received over 300,000 views.

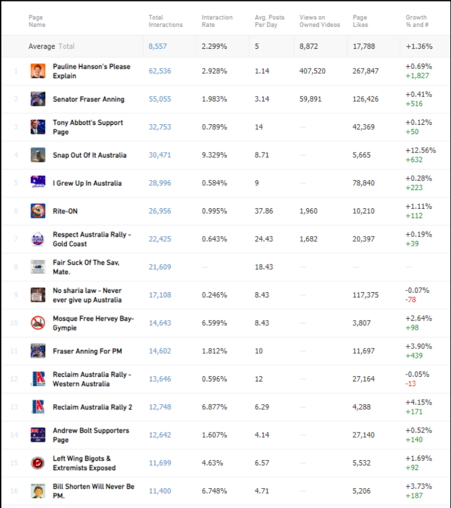

During the election campaign, CrossCheck Australia examined the traction of hundreds of Australian Facebook pages and groups in the social media monitoring platform CrowdTangle, including political parties, unofficial support groups, activists and grassroots groups. Pauline Hanson consistently topped the list of the highest performing pages.

By contrast, Clive Palmer – Hanson’s right wing rival in Queensland – focused on a multi-million dollar advertising campaign. His Facebook page has over 200,000 followers but his advertising blitz on both traditional and social media lacked the personal touch of Pauline Hanson.

In the end, Palmer didn’t win his Senate bid nor a single parliamentary seat for his United Australia party. His party claimed 3.4 % of the national vote, but Mr Palmer himself fell well short of the number of votes needed to win a Senate seat.

Hanson remains a Senator – she’s not up for re-election until 2022. Her party won 3.1% of the national vote in the 2019 election. In her home state of Queensland, voters shifted in large numbers from Labor to One Nation. There was a 3% swing towards One Nation – compared to a 3.47 % swing against Labor – in the state.

By focusing on polls, the media may miss how these ‘theme and variations’ resonated with communities online and affect their offline opinions.

Most opinion polls and media coverage focused on the two horse race between the two largest parties, Labor and the Liberals, predicting (incorrectly) a win for Labor. The problem with this approach is that by focusing on polls, the media may miss how these ‘theme and variations’ resonated with communities online and affect their offline opinions.

While they have a much smaller share of the vote, larger voter swings actually went to Clive Palmer and Pauline Hanson’s right-wing parties. It’s important to understand their tactics and appeal. Other hyper partisan groups also shared a spate anti-Muslim content strengthened through social media amplification during the campaign.

At the same time, it’s not just small hyper-partisan groups behind the speed and power of mis – and disinformation that is beginning to take hold through social media in Australia. In the case of the death tax scare campaign, it was a combination of the main political parties, fringe groups and the dynamics of social media platforms that enabled the distorted kernel of truth to live on, in various guises to various voters, however many times Labor denied it.

As Crikey reporter Christopher Warren noted in a recent article, this was “an election where social media enabled profoundly different experiences, some of them shifting with deep ocean currents, others interacting with the visible media world.” We need to keep covering these deep ocean currents, to help us better understand the visible world.

To stay informed, become a First Draft subscriber and follow us on Facebook and Twitter.