In the immediate aftermath of newsworthy incidents, the debunking of fakes now takes up a much larger part of verification work compared to when I first started in the field in mid-2011. Only a few years ago, most of the unreliable information seemed to come from people making mischief or trying to show that they were in the know. Now, systematic manipulation of online information appears to be widespread.

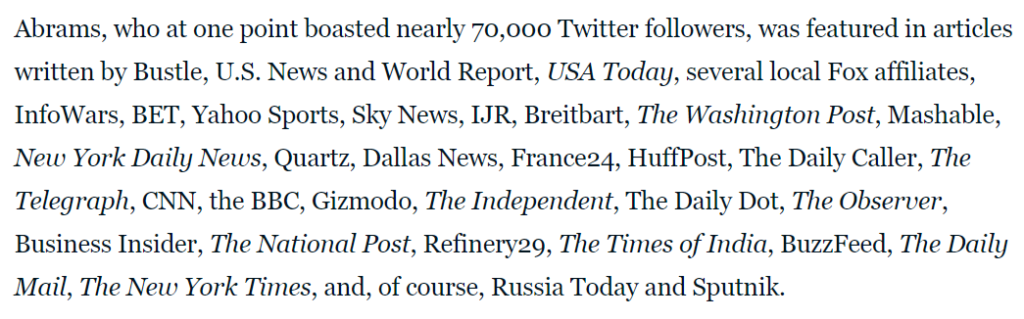

Over many months, before and after the 2016 US presidential election, tweets from a “Jenna Abrams” on a broad range of topics were included in news articles far and wide. There was one major problem: Jenna Abrams didn’t exist, and the account has been described by US congressional investigators as a Russian propaganda front.

Now, if you’re inclined to think that only small, amateurish newsrooms would carry quotes from someone they hadn’t confirmed existed, check out this roll-call:

Credit: The Daily Beast, “Jenna Abrams, Russia’s Clown Troll Princess, Duped the Mainstream Media and the World”

At First Draft, we’ve tried to distill what we have learned –through our own experiences and our cooperation with news professionals and educators – into training that helps individuals quickly acquire the core skills needed to avoid this. Our verification mini-course takes you through all the essentials, and provides a foundation for further development and learning.

Access our free, one-hour course by going to https://firstdraftnews.org/learn and clicking the ‘Get Free Access’ button.

When I joined First Draft in July 2017, I was motivated largely by the belief that verification should be a basic requirement in newsrooms and for anyone dealing with information. This was inevitable after nearly six years working full-time in monitoring, discovery and verification of online content.

In that time, a noticeable shift occurred in the requirements for journalists working in that space. A great deal of the emphasis moved away from wide-eyed pursuit of “authentic” content for illustrating breaking news stories; a major concern became learning to deal with clever and motivated actors seeking to profit from what First Draft’s leader, Claire Wardle, refers to as “information disorder”.

No event pushed verification to the fore as much as what became known as the Arab Spring. The wave of unrest that swept parts of the Middle East and north Africa, beginning in 2010, had several features that made new systems and techniques a necessity.

In Tunisia, Egypt and several other countries, protests and clashes were taking place in an ever-increasing number of locations, some far from capitals or major population centres. This provided a challenge to even the best-resourced newsrooms and the most intrepid reporters.

International media, meanwhile, were from a very early stage deprived of free access to large parts of Syria. This didn’t translate directly to a lack of material, but those seeking to illustrate reports of the conflict with visuals were dependent on what was inelegantly termed “UGC” – user-generated content. This content, and its sources, needed to be be vetted for authenticity and reliability.

Over the years that followed, online verification became a key part of multi-faceted investigations by the likes of First Draft founding partners Bellingcat and Storyful, The New York Times, and projects such as the award-winning CrossCheck. These showed the value of combining new skills with the fundamental techniques and practices that have been part of journalism for generations.

But for every newsroom tracking weaponry across international boundaries or trying to monitor vast swathes of social media in the run-up to an election, there are countless others where the most rudimentary verification practices have yet to take root. For every journalist who can confirm the location of a video via a fleeting view of a distant building, there are many who don’t realise it can take just seconds to check whether the dramatic photograph they’ve just seen on Twitter has appeared online previously.

Meanwhile, the methods and networks used to disseminate disinformation have developed significantly. My former colleagues at Storyful tracked how memes and fake stories were conceived and planned on less popular networks such as 4chan, and closed networks like Discord. Coordinated campaigns then shifted these to the bigger social networks, where they attracted enough attention to be picked up by mainstream media outlets.

Technology – and the sophistication of “bad actors” – will only continue to develop. It is essential for journalists to have the skills they need to fight back.

I’m confident that what First Draft provides is by its very nature objective and non-partisan. What the course introduces are tools and skills; these can be used equally by anyone, regardless of political affiliation.

The phrase “knowledge is power” may be a cliche, but consider: Democracies function on the basis of choices made by their people. Faulty information means faulty choices. A public expressing its will through the ballot box on the basis of faulty information is a disempowered public.

First Draft’s online course forms part of our modest effort to address this. We hope it’s the beginning of a long association with accuracy and objectivity in media and beyond.

Access our free, one-hour course by going to https://firstdraftnews.org/learn and clicking the ‘Get Free Access’ button.