Their misleading, attention-grabbing campaign videos are viewed by thousands — sometimes hundreds of thousands — of voters. But just how much influence falsehood-posting fringe candidates have online is often skewed. This was on full display in London’s mayoral elections last week.

Several candidates used misinformation to gain status online, tapping into conspiracy theory communities and challenging the existence of Covid-19 and the safety of vaccines.Their Facebook and Twitter followings vastly exceed their offline support.

“These types of figures know how to get audience attention, so [they] rely on mechanisms like social media to gain attention,” said Aliaksandr Herasimenka, a researcher at the Oxford Internet Institute who investigates how political groups use social media to manipulate. “They provide new opportunities for new figures as they overcome traditional gatekeepers quicker and reach attention faster.”

From conspiracy theory site to mayoral campaign

Many Londoners are accustomed to seeing the face of Brian Rose plastered on highway billboards and “Brian For Mayor” leaflets delivered through their mailboxes, but his brand was largely built online. The former banker utilized the pandemic to grow his YouTube channel London Real, which regularly promotes misinformation and conspiracy theories. Through spectacle and shock, he’s attracted much recent media attention, including a video in which he drinks his own urine.

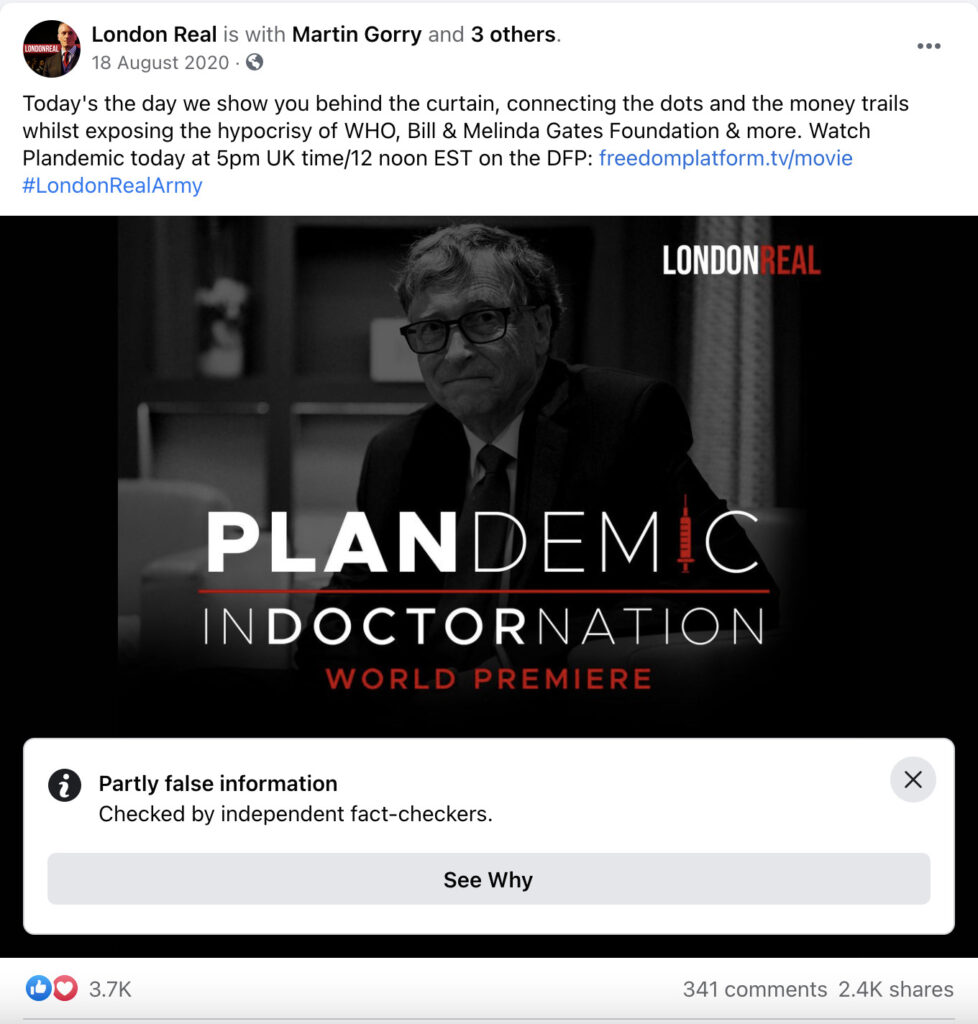

In 2020, Rose crowdfunded nearly £1 million for a “Digital Freedom Platform,” a video-hosting space exclusively for conspiracy theory videos, such as the viral “Plandemic” film, which was banned by Facebook and YouTube. One of the top most interacted-with Facebook posts containing a link to the “Digital Freedom Platform” promoted “Plandemic,” attracting more than 2,400 shares. Facebook has labeled the post as “partly false information.”

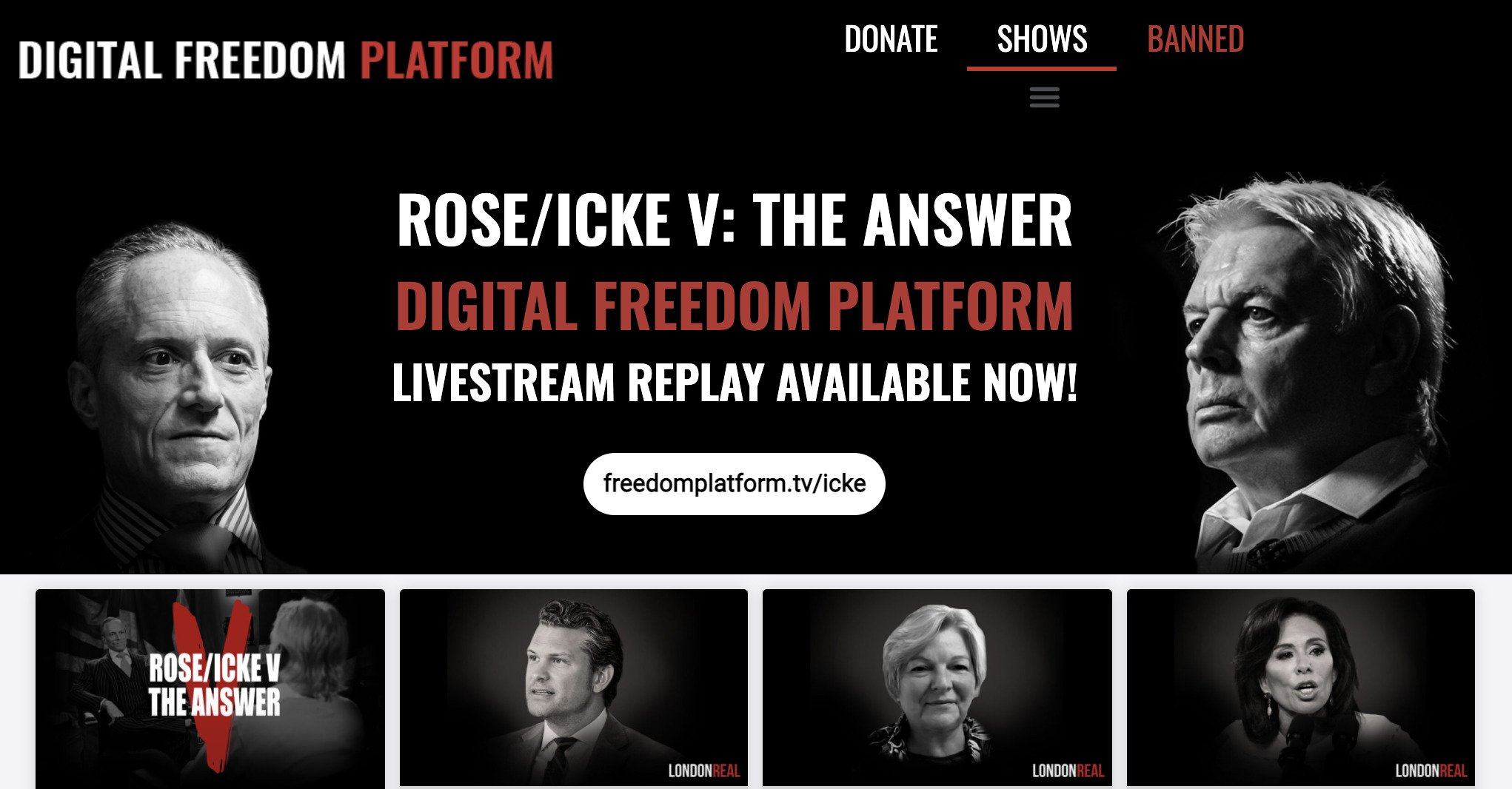

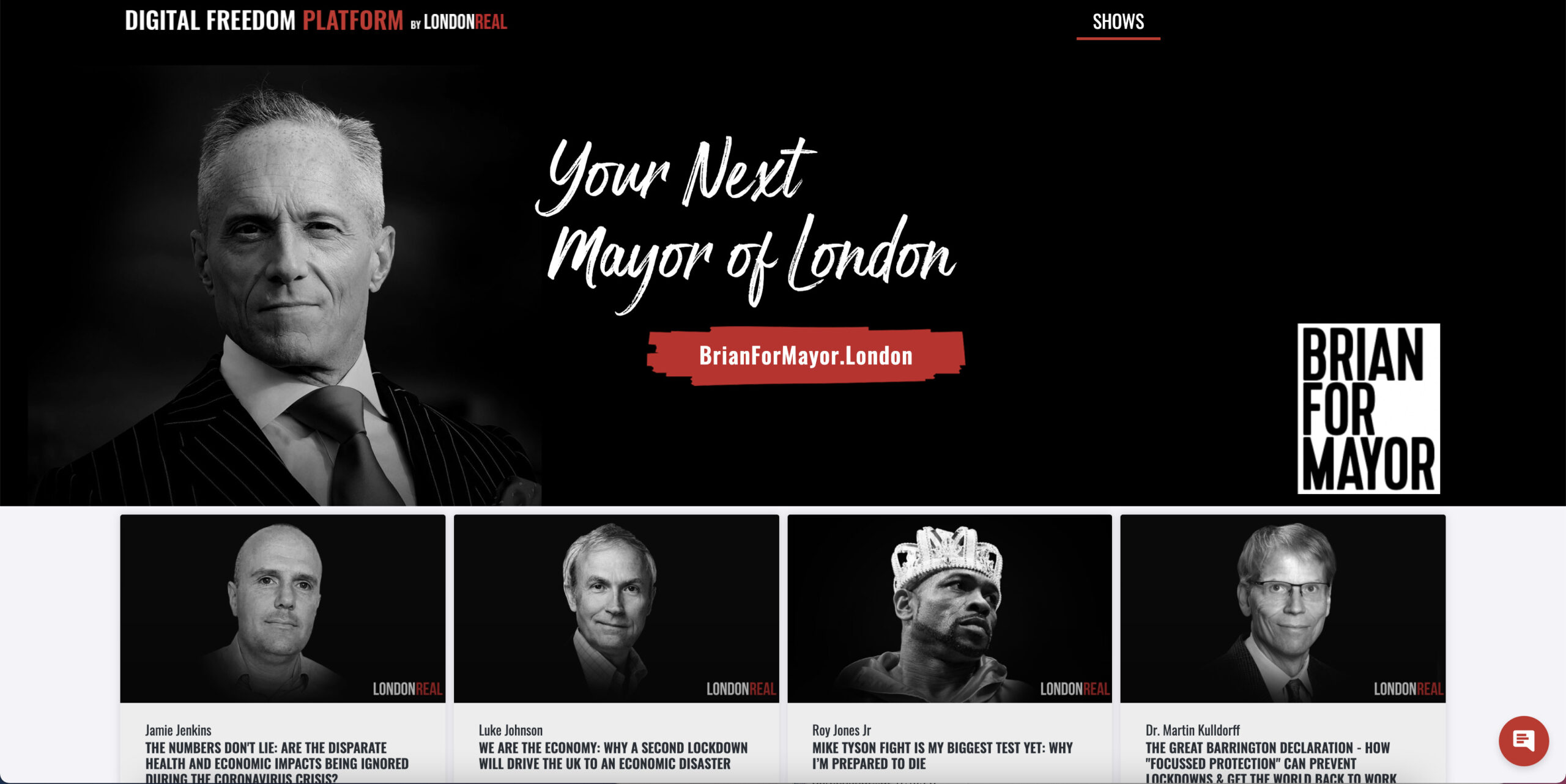

Rose used the same digital destination — freedomplatform.tv — to solicit donations and promote his campaign for London mayor. The landing page of the website previously featured grayscale photos of conspiracy theorist David Icke and “Plandemic” subjects. Now, with a similar aesthetic, Rose’s campaign portrait appears alongside the slogan “Your Next Mayor of London” and his “Brian for Mayor” logo.

Freedomplatform.tv promoting a video interview with David Icke on June 21, 2020. Screenshot by author

Freedomplatform.tv promoting Brian Rose’s mayoral campaign ahead of May 6 vote. Screenshot by author

His personal Instagram account, @therealbrianrose — where he posts more frequently than he does on Facebook — grew from just over from 264,743 on May 31, 2020 to more than 1.68 million in the runup to the May 6 elections, according to Facebook monitoring tool CrowdTangle.

Meanwhile, London Real’s Instagram following ballooned from 110,608 in June 2020 to almost 1.35 million over the same period, with its Facebook following growing from 194,187 in December 2019 to more than 750,300 in late December 2020. The number of followers has marginally declined to 631,000, but for context, the Facebook page for Sadiq Khan — who secured a second term in the vote — currently has about 743,000 followers. Conservative candidate Shaun Bailey, in second place, has just over 32,500 Facebook followers.

Despite these numbers, Rose enjoyed just 1.2 per cent of London’s support in the mayoral count.

YouTube ads inflate viewership

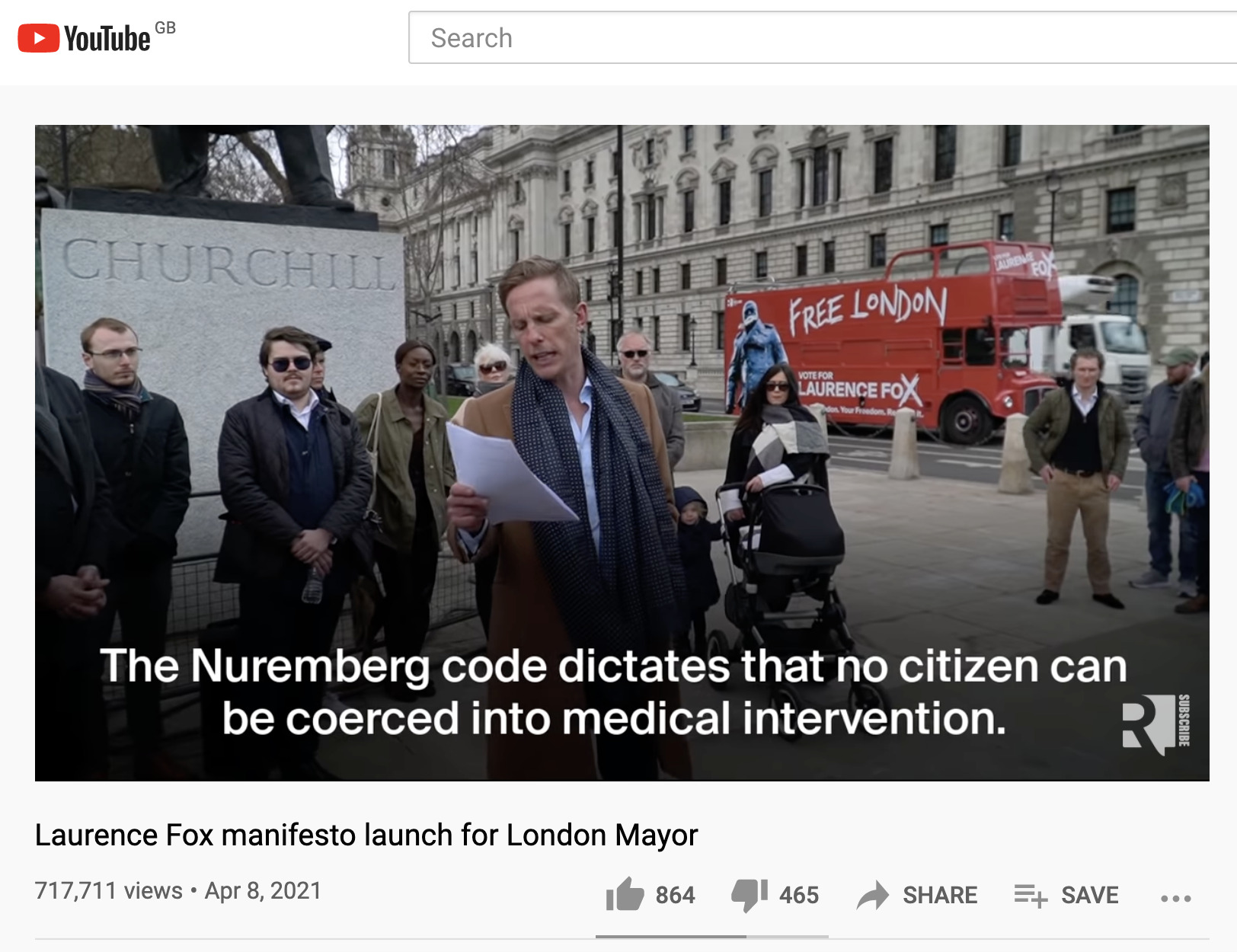

Laurence Fox, an actor who ran as mayoral candidate for the Reclaim Party with a program that emphasized opposition to lockdowns, was dubbed the “anti-woke” candidate amid widespread criticism. His party paid to promote a YouTube video outlining Fox’s manifesto, which has been viewed at least 716,000 times since it was posted April 8. Fox got 47,634 votes (1.9 per cent).

In comparison, a video promoted by the Labour Party for Khan, who was re-elected with 55.2 per cent of the popular vote, got around 44,900 views. (This video was identified through Google’s Political Advertising Library, Google being the company that owns YouTube.)

Taking out digital campaign advertisements is common practice and of more benefit to lesser-known candidates such as Fox. But more concerning is that the Reclaim Party candidate used the promoted YouTube video to spread misinformation about the Covid-19 pandemic, artificially reaching a wider audience. In comparison, most of Reclaim Party’s unpromoted videos receive 2,000-11,000 views apiece.

In the manifesto video, Fox falsely claims: “The Nuremberg Code dictates that no citizen can be coerced into a medical intervention. But that is what our fearmongering government have done relentlessly for the last month. ‘Take the jab, have your freedom back.’ No. Enough is enough.”

References to violations of the Nuremberg Code, which addressed experiments on human subjects in the wake of atrocities committed by the Nazis, are part of a false narrative that has been circulating online for months by accounts seeking to sow doubts about the safety of Covid-19 vaccines.

Promoted Reclaim Party YouTube video for Laurence Fox’s campaign. Screenshot by author

According to YouTube, the video does not appear to violate its advertiser policies or Community Guidelines, including Covid-19 content that explicitly contradicts expert consensus from local health authorities or the World Health Organization.

More engagement than second favorite

Lesser-known fringe candidates are also benefiting from amplification while promoting misleading pandemic content. David Kurten, a London Assembly member running as the Heritage Party candidate, saw his Twitter follower count rise from 27,700 to 68,900 over the last year, as he consistently promoted conspiracy theories that mRNA vaccines are “rushed,” “experimental” and made from aborted fetuses. As part of his mayoral campaign, he was a vocal critic of so-called “vaccine passports” and frequently voiced his opposition to Covid-19 testing, masks and vaccines in Twitter posts with thousands of likes and retweets.

CrowdTangle data reveals that the number of interactions Kurten’s Facebook Page received in March was topped by only one other candidate’s Page — Khan’s. Kurten’s Page received over three times as many interactions as Shaun Bailey, the candidate for the Conservative Party, who trailed Khan with 44.8 per cent of the vote. Kurten won just 0.4 per cent.

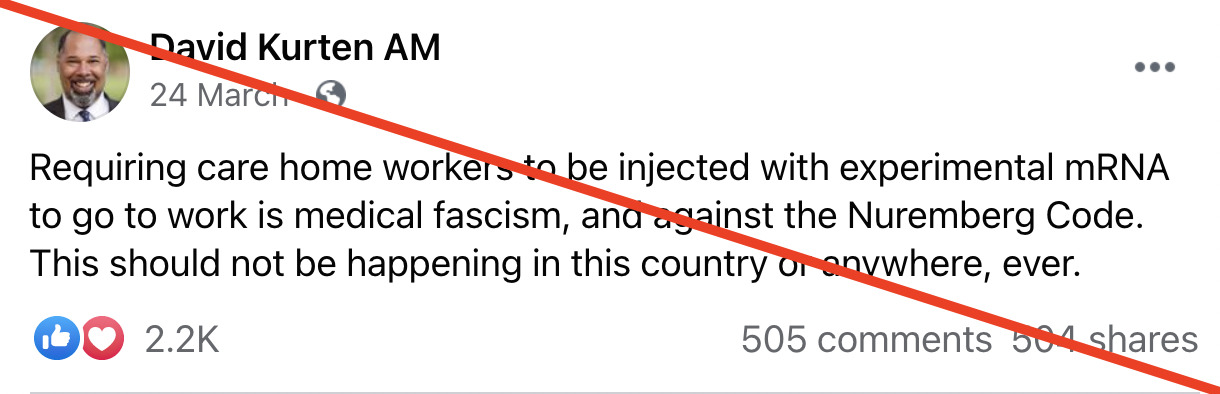

Kurten’s posts and videos that promote anti-lockdown events and misinformation about the pandemic received the most interactions. The top post for March and April was an image from the “London Freedom Rally,” a protest against lockdown measures. The second most interacted-with post pushed a number of false claims about mRNA vaccines and “medical fascism.”

Facebook post on David Kurten’s Page [screenshot by author]

Kurten’s YouTube account was temporarily suspended at least once. Facebook took action against Kurten’s Page a day before the election, issuing a week-long ban on posting or commenting because of a breach of Community Standards. The platform removed a couple of posts containing false claims flagged by First Draft; however, similar falsehoods posted by Kurten remain. Twitter has not taken action against Kurten’s continued promotion of conspiracy theories. A spokesperson for Twitter said, “[w]e prioritise the removal of content that represents a clear call to action that could potentially cause real-world harm.” The spokesperson added that Twitter had removed over 22,400 tweets since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic and challenged 11.7 million accounts under its policy on misleading information about Covid-19.

A Facebook spokesperson told First Draft: “We are taking aggressive steps to fight harmful misinformation about Covid-19 and approved vaccines and have removed the violating content brought to our attention [referring to claims containing misinformation flagged by First Draft].”

Why is this happening?

The Covid-19 pandemic has provided fringe candidates with additional space, attention and audience. “Anti-maskers, anti-lockdown supporters, anti-vaccination activists … [pandemic] restrictions are not supported by everyone so people look for people who voice their outrage,” said Herasimenka.

Platform policies and enforcement are also falling short and helping fringe figures climb the rungs of popularity. Google, Facebook and Twitter have pledged to limit Covid-19 and vaccine misinformation, but misleading claims and conspiracy theories continue to slip through the cracks. Google has even accepted payment for political advertisements containing misinformation.

“Generally there’s inconsistencies across platforms regardless of whether they’re political candidates,” said Anna-Sophie Harling, managing director for Europe at NewsGuard, which tracks misinformation. “Part of the issue is there’s no transparency.”

The issue is by no means restricted to the UK. For example, in France, where presidential elections are planned for April next year, several minor politicians have gained traction by promoting Covid-19 misinformation. They include Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, leader of “Debout la France” (Stand up France). Between April 4 and May 4, two of the ten most-shared Facebook posts about vaccines in French* were Dupont-Aignan’s; both contained misleading information about Covid-19 vaccines being administered to those under 18. They received some 9,500 and 8,100 shares respectively; President Emmanuel Macron’s most-shared post about vaccines* received only 641 shares in comparison.

*search string: vaccin OR vaccins OR pfizer OR astrazeneca OR moderna OR vaccination OR vacciné OR vaccinée OR vaccinées

Careful reporting about these candidates could help reduce information disorder, said Kendrick McDonald, a senior analyst at NewsGuard. “There’s a lot of shock value and if you’re going to cover a story on a mayoral candidate drinking his urine for clicks, it would be disingenuous to not contextualize their attention-seeking activities in a broader context of their history.” Covering these stories can have the undesired effect of amplifying misinformation, so responsible reporting is key.

Despite the lackluster numbers London’s fringe candidates showed at the polls, the offline ramifications, such as protests and mask opposition, can be damaging. “Content that erodes trust in democratic institutions can be harmful in the long run,” Harling said.“It’s important that we pay attention to online discourse and the power platforms have.”

Stay up to date with First Draft’s work by becoming a subscriber and following us on Facebook and Twitter.

This article was updated on May 10 to add a statement from a Twitter spokesperson.