Monitoring the election fraud claims that raced through social media during the US presidential election and Bihar’s state election in India, it is hard not to notice the stark discrepancies in how Facebook and Twitter treated these misleading assertions. As these posts picked up thousands of shares and likes, spreading false claims to voters faster than fact checkers could correct them, the social media giants took steps to label misleading or debunked allegations of fraud spread by politicians in the US. Curiously, however, Indian politicians appear to have been given free rein to disseminate similarly misleading accusations to their hundreds of thousands of followers during Bihar’s elections.

Let’s start with Facebook. When President Donald Trump made a series of baseless fraud allegations on its site during the US election period, the platform intervened, providing critical context for audiences.

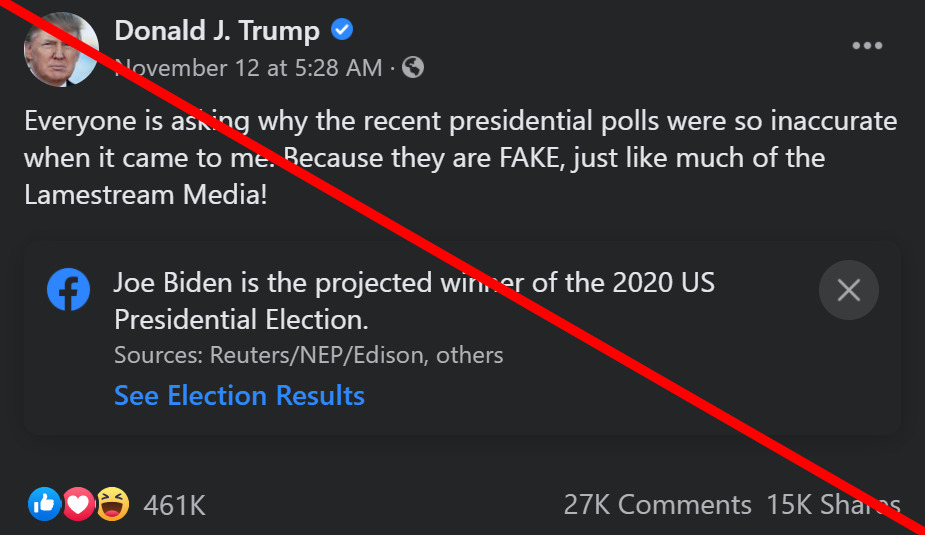

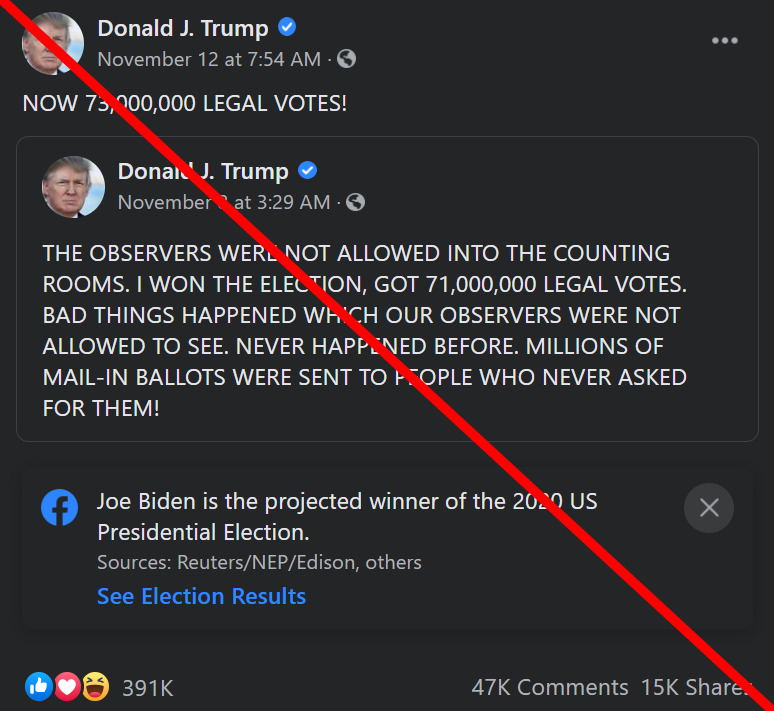

For example, Facebook labeled Trump’s November 7 Facebook post alleging ballot fraud, including the claim that “OBSERVERS WERE NOT ALLOWED INTO COUNTING ROOMS.” It also labeled his November 12 post calling presidential polls and the media “FAKE.” In both cases, the label stated that “Joe Biden is the projected winner of the 2020 US Presidential Election” and cited several news sources for context.

Though similarly baseless claims of electoral fraud were made by Indian politicians in the Bihar election, Facebook did not apply any labels or otherwise offer readers additional context.

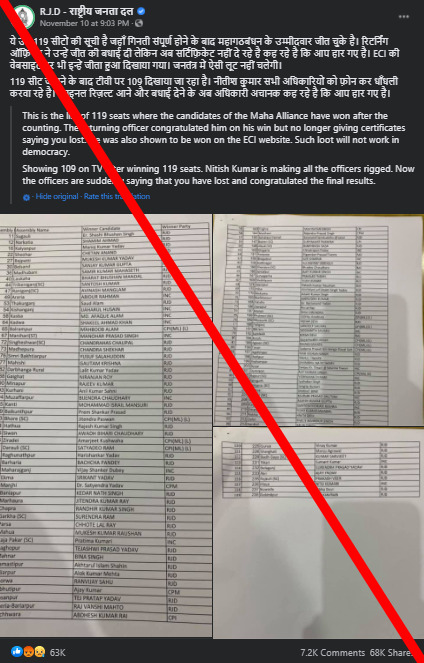

Take some of the claims from the RJD, the main opposition party contesting the elections in Bihar. The RJD and its ally, the Congress party, repeatedly alleged fraud in online posts. On November 10, as the election results were still coming in, the RJD posted in Hindi that it had won the election, accusing an opponent, sitting chief minister Nitish Kumar, of calling the election officials to rig the vote. Even though India’s Election Commission has refuted the claim, this unlabeled post has received 68,000 shares on Facebook.

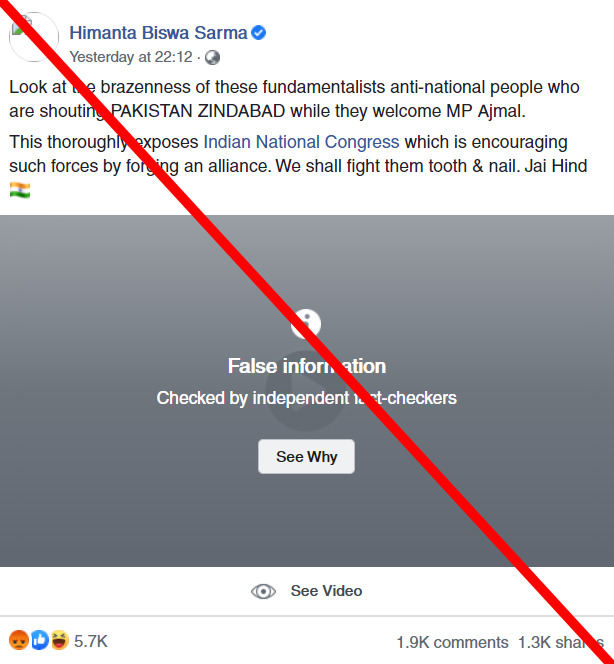

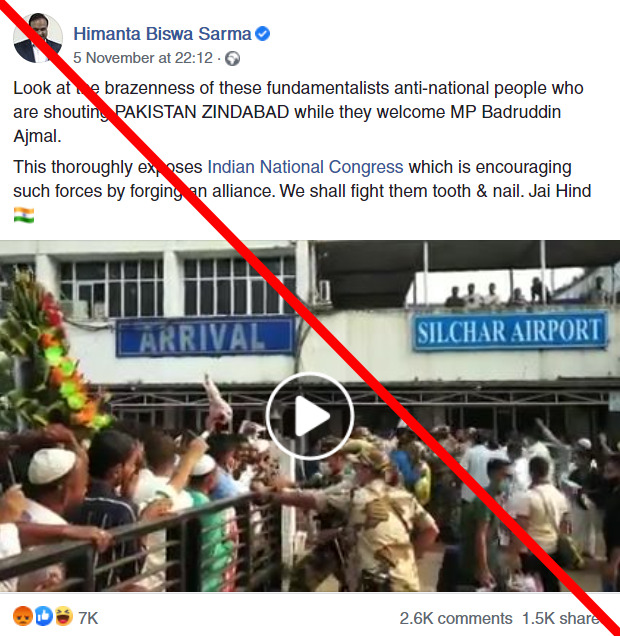

Generally, politicians’ speech is exempt from Facebook’s third-party fact-checking program, and Facebook applies this rule consistently in the US and India. Gray overlay labels indicating false or misleading material (based on the independent fact checkers’ conclusions) have not been applied to Trump posts, and Facebook does not apply them to Indian politicians’ posts either. In fact, the company removed a “false information” overlay from Indian minister Himanta Biswa Sarma’s November 5 post (alleging opposition party supporters were chanting pro-Pakistan slogans — a claim Boom Live debunked), telling The Indian Express the label had been applied in error to exempted political speech.

However, as shown above, the company found a way outside of the fact-checking program to label misleading posts by Trump, but not those by Indian politicians.

It’s not just Facebook that has treated debunked or misleading election claims in India differently — similar discrepancies play out on Twitter as well. The platform labeled Trump’s November 14 tweet suggesting fraud by Georgia election officials and claiming that he “won the state,” but did not label similar accusations from political figures in India, even when they have been debunked.

For example, Congress leader Vijay Singh’s November 15 claim (now deleted) that Bihar’s “entire electoral process is rigged,” featuring a video of a woman he suggests is a polling officer in Bihar, was debunked by The Logical Indian, which found the video was not filmed in Bihar. Singh’s tweet went unlabeled on the platform.

Similarly, a misleading tweet from the RJD’s official account that used an old debunked video to show alleged ballot tampering was not flagged by the platform.

The difference in treatment can’t just be explained by the audience size of the speaker. In the US election, it wasn’t just the president who received labels. Fraud claims from state-level Republican party officials (such as David Shafer, chairman of the Georgia GOP), unelected political operatives (Mike Roman) and US congressional candidates (Marjorie Taylor Greene) also received labels from Twitter, even though all three figures have smaller Twitter audiences than the Indian political figures and parties mentioned above.

Nor can the differences be dismissed by saying that the Bihar elections were merely regional elections, as opposed to the US presidential election. In 2018, shortly before the midterm elections in the US, Facebook publicly announced an expansion of its voting misinformation policies, including a ban on posts containing false information about how to vote or whether votes are counted. The example Facebook used in its statement then drew from the US political system. But no such announcements were made ahead of Bihar’s election, and it is unclear whether the 2018 measures were applied to protect the integrity of the election in Bihar.

This raises questions about why platforms are treating claims from political figures and parties in India and the US differently. Does the ability of voters in Bihar to access quality information matter less to Facebook and Twitter than the ability of voters in Michigan to do the same? What do these companies’ decisions say about the importance of election integrity in different countries?

Is it because Facebook and Twitter lack enough moderators who speak Hindi or another local language that election misinformation from Indian politicians is allowed to proliferate? Considering that India is one of the world’s biggest social media markets, what could platforms be doing to improve the online discourse around elections there? As the National Herald points out, the stakes might be higher when platforms such as Facebook allow politicians leeway to spread misinformation at the same time activists and journalists are being imprisoned for criticizing the Indian government on social media.

In a promising step forward, Twitter recently applied a “manipulated media” label to a November 28 tweet from Amit Malviya, who heads the Information & Technology department for the ruling BJP party and is known to have spread misinformation in the past. Malviya’s tweet was not election-related — it addressed the ongoing farmers’ protests in India — but this was one of the first times Twitter has applied such a label to an Indian political figure. It remains to be seen whether Twitter will keep up and scrutinize future elections in India in the same way. When questioned about their election misinformation policies, a Twitter spokesperson told First Draft via email that the company recognizes different elections around the world, with “varying levels of Twitter usage,” require different kinds of support. The company said it “will continue working to protect the integrity of the election conversation on Twitter worldwide. We research, question, and change our approach to respond to the specific behaviors we see. We will build on this effort considerably in 2021.”

Facebook has not responded to First Draft’s requests for comment on its election misinformation policies.

Content moderation can be a fraught process for social media companies and notoriously difficult to get “right” — especially when it comes to political speech and election integrity. But by choosing to moderate election claims in only a few select countries, the platforms end up privileging the information ecosystems of voters in some places but not others. At the very least, they should explain those moderation challenges and the reasons behind the inconsistencies. If they do not, to quote Rasmus Kleis Nielsen, the director of Oxford University’s Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, they “risk ending up joining the long list of Western companies who treat people in other countries as second-class citizens.”