The sun, sand and sea of Rio de Janeiro are as legendary as the statue of Christ the Redeemer overlooking Brazil’s second-largest city but, as summer moves into autumn, fog can cloud the coastline of the bay before the sun hits its stride.

Such was true on the morning of March 3 2014, when 22 year-old Marina Pinto Borges left for work. Crossing the famous Rio-Niterói bridge to the city, Borges slammed on the brakes and, the road slick with rain, lost control of her Renault Sandero, flipping over a guard rail and plunging the full 70 metres into the sea below.

Quite the fall: The Rio-Niterói Bridge (public domain)

Borges survived the fall, the first person ever to do so, and the first news organisation to report her escape was local radio station CBN. But rather than receiving a tip from the emergency services or a call from a bystander, their source came from WhatsApp.

“We thought it was impossible, but it was true — a driver saw the accident,” Juliana Duarte, a journalist with CBN, told Nieman Lab last June.

Nearly 18 months later, the top four messaging apps now boast more monthly active users than the top social networks, and many news organisations have established channels on WhatsApp and other private networks to share stories.

Established wisdom on using chat apps for newsgathering is still hard to come by, however.

Trushar Barot, mobile editor at the BBC World Service, has been monitoring and experimenting with chat apps use in news since the London riots in 2011 when rioters stayed one step ahead of police and journalists by co-ordinating their movements on BlackBerry messenger.

Having launched BBC services on a number of platforms since, and winning a Peabody award for public service journalism by setting up a WhatsApp information service in West Africa around Ebola, he published a study into chat apps and news through the Tow Center earlier this week.

As well as offering important insight into how many chat app users receive and interact with news organisations and the apps themselves, the report details instances where news outlets have sourced exclusive stories and footage.

Barot shared some more advice with First Draft fort news organisations and journalists looking to meet their readers where they are.

Different platforms for different markets

Unlike the big social networks, which act as a global town square where citizens of the world share information and interact, chat apps are small pockets of friends, digital community centres connected by their members rather than the platform.

As such, news outlets need to consider who they are trying to reach before setting up their private network accounts as platforms are more popular with different communities.

“It’s very much about thinking where the story is geographically and then trying to pick and choose what we think is the right potential chat app to engage audiences in,” said Barot.

While WhatsApp has the largest global reach, it is particularly prevalent in India and South Africa, for example. Japanese chat app Line is strongest in its home country, Taiwan and Thailand, while WeChat is more popular across China, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

Kik was established with the intention of being the “WeChat of the West”, gaining a largely North American userbase in the process, and Viber was founded by a team of Israelis and Belarusians, becoming most popular in Russia and the Middle East as a result.

Telegram, with it’s emphasis on security and encryption, has been more popular in countries like Iran, Iraq, Uzbekistan and other countries “where there is greater government control and privacy issues are much more exacerbated”.

“We knew that Telegram was rising rapidly in use in Iran specifically for these reasons, where the government bans consuming BBC News content through television,” Barot said, so the BBC launched a channel on Telegram with the BBC Persian service.

The website is also blocked in Iran but, within two weeks of launch BBC Persian had more than 100,000 subscribers on Telegram and some posts reached over 800,000 unique users in the app, “by far the most significant numbers we’ve ever experienced on any chat platform,” said Barot.

“If something happened in Iran we would try to use Telegram and, in [some] ex-Soviet states, Telegram is used increasingly more than any other chat app.

“But in large parts of Asia it’ll probably be WhatsApp or something like Line, so it’s very much a case of trying to match and fit the right app for what we think is the story for where users are most likely to use it.”

The BBC is, perhaps, unique in its size and scope in being able to cater to audiences all over the world, but that doesn’t mean smaller organisations can’t take advantage of the opportunities chat apps present.

Reaching communities on closed networks

So where to start?

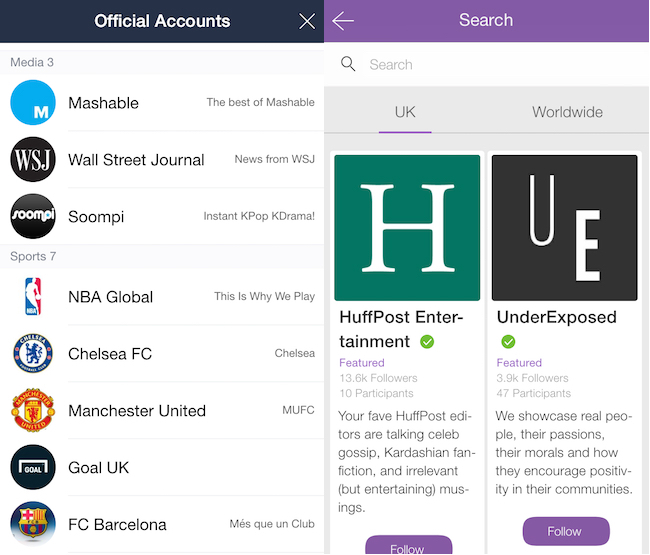

Some platforms like Viber and Line have public sections of the app for official accounts, but most platforms need a more pro-active approach to find and grow communities, like any social network.

At the BBC, Barot said the first phase comes in promoting the channel or phone number associated with the platform on all the existing channels: social media accounts, websites and any relevant broadcast platforms.

“Usually after a couple of weeks or a month, when we’ve accrued subscribers through that organic reach, we’ll then try to push out a message to those existing subscribers to encourage their friends and contacts in the app to also subscribe,” he said, “and that brings in more people hopefully. That way we’re tapping in to their networks inside those apps as well.”

Engaging with users in chat apps is as much a two-way process as any other digital platform, so news organisations need to build a community through sharing stories and information in the chat app of choice if they want users to reciprocate.

Newsgathering

Many posts to chat apps from BBC channels invite the audience to respond in some way and build a relationship. That doesn’t mean they always will, but it is a constant reminder that the option is there, “so if anything happens anywhere that they are it would be incredibly easy for them to contact us and send that content,” Barot said.

“It’s as much about ingraining into people’s thinking that they are able to send us content or messages through these platforms so we don’t get into the position where we only view them as a push distribution opportunity, but really include a return path for them as well.”

In addition to the distribution channel, BBC Persian set up a separate channel for the Iranian public to share tips and multimedia files which quickly became a gold mine for stories.

“Since they launched on Telegram they’ve been absolutely inundated with content that’s come in,” Barot said. “Some of it is spam but a lot of it is from parts of the country they’ve never got content from before and Telegram is proving to be a great medium for them to solicit really valuable intelligence and material.”

The high-security nature of Telegram can make it difficult to contact the source in some cases, but on platforms like WhatsApp, which include the user’s phone number by default, the newsgathering process is more efficient than some more open social networks.

“So if it’s an earthquake in Nepal and you’re getting messages with a Nepal phone number you know to prioritise what that message is saying, or who that person is, and that helps sort the wheat from the chaff much more quickly.<

“Secondly, because it comes with a mobile number you’re immediately able to pick up the phone and call them and get that kind of clarity. Quite often that’s much more difficult if people send you content on Facebook or you see stuff on YouTube or Twitter or Instagram, where you have quite a limited mechanism to reply back to that user and hope they message you back, maybe in a private message, with their contact details.”

Verification

It may be easier to contact sources through platforms like WhatsApp but establishing the provenance of what they share can be much more difficult. A picture or video may get passed around a group before it reaches a news organisation but without any information as to where it originated, making it very difficult to backtrack to the where it came from.

“We’ll get a lot of people sending the same video on WhatsApp,” said Barot, “and they’ll say it was passed on by a friend. In those situations it’s often very, very difficult to get through to the original poster because there’s no original tweet to get back to and say ‘here’s the original link’.”

The principles of verification still remain though, he said, and although simple checks like reverse image search may immediately expose an image as fake or old, getting to the origin of a picture or video is still vital.

“We’d want to know who sent the picture, whether they took it themselves, what the context of it was and then making an assessment ourselves about whether what they’re telling us is the truth or not.”

Contributor safety

The private nature of chat apps means it is a preferable channel for some users who wish to remain anonymous, making it easy to protect their identity, but the same duty of care for the well-being of sources should apply no matter how they were found.

Newsrooms need to consider “to what extent is a person sending that material in danger,” said Barot, “to what extent, even if they want their names to be used, could they be under threat if we reveal the source.”

This may even go against the wishes of the contributor, but news organisations are generally more aware of the fallout from going public than members of the audience themselves, so should use their judgement accordingly.

“There have been some examples where people have sent us content from Libya or Iran and have said ‘I’m happy for you to use my name’, but we said we’re not going to or we’d anonymise it by just using the first name because we felt that was important, even if they were fine with it. We over rode their safety considerations they may have themselves and made our own judgement.”

The full study from Barot and Block Party CEO Eytan Oren, ‘Guide to Chat Apps’, is free to read and download through the Tow Center.