The days of journalism as a one-way conversation are over.

This statement isn’t breaking any new ground: media pundits have been heralding social media as a revolution in publishing for the best part of a decade, defining print and broadcast media as a historical anomaly, as The Gutenberg Parenthesis that momentarily took the power of storytelling away from the wider populace.

But news organisations have been largely slow to catch on, with their shipping-tanker turning circles of institutional change. The habits of hundreds of years are hard to break, or at least bend, and it’s difficult to change the railway tracks while the train is still running. But that doesn’t mean outlets aren’t aware of the need to engage with their audiences online.

“We kept hearing that everyone at this point knows how to use Facebook and Twitter, but people kept telling us they don’t really have anyone in the hiring pool that knows how to use those tools in a more sophisticated way,” said Dr. Carrie Brown, head of the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism’s social journalism masters programme. “[Someone] that understands what this community engagement thing that everyone is talking about is. But what does that actually mean? How do you do it?”

Now nearing the completion of its first year, her course is hoping to change that.

One student has been working with communities in Brazilian favelas, teaching the “mobile-driven” journalism skills and getting them to contribute stories and tips. Another focuses on African American’s with mental health issues, trying to remove the stigma and persuade them to share information that can benefit all. A third has chosen the work of social journalists as her beat, a “meta-community” of working news professionals on Twitter her can better understand their work and the industry by coming together.

“The idea is trying to teach journalism as a service rather than as a product,” Brown told First Draft, “and trying to get our students to explore better how they can really build relationships with people in communities, better understand what they need and how to deliver it in a way which is most relevant to them.”

The course is built on the “five pillars” of social journalism: listening, journalism, data, technology and business skills. Combining all five should give journalists the skills to put the core philosophy into practice, and easily adapt to new challenges and technology that will doubtless continue to emerge from the ever-evolving digital landscape.

Jeff Jarvis describes the thinking behind the social journalism MA at last year’s ONA conference, before the course began

And listening is fundamental to any kind of success where social media is concerned, believes Brown, and should be the starting point for any digital strategy.

“If you really understood a bit better how people where thinking about problems and challenges and how to solve them you could take the stories that you know are important and make them more relevant and more interesting so [the audience] can really understand why they need to pay attention.”

Again, this shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise to most journalists. Understanding the audience is, after all, the currency by which publishing empires rise and fall, but it takes on new forms online.

The success of BuzzFeed, Vice and AJ+ among younger generations comes from an almost preternatural second-sight on social media: implicitly understanding what their audience wants and delivering it the way they want it, largely because the staffers and audience are one and the same.

As the number of information sources has exploded, it is even more important to engage readers in the process but local outlets, especially in the UK, are often guilty of ignoring this fact. Haemorraging money through the revenue hole created by declining classified ads, too many were slow to jump on the digital bandwagon beyond a vague nod towards a website and social media presence.

Worryingly common practice: A local news outlet in the UK recently forced readers to jump through hoops before finding out if their children were affected by a bomb scare (Screenshot from Barrhead News)

Worryingly common practice: A local news outlet in the UK recently forced readers to jump through hoops before finding out if their children were affected by a bomb scare (Screenshot from Barrhead News)

Those who dove in early are now reaping the rewards, however. The Texas Tribune, for one, established an events arm in 2009 that was reaping over $1 million within four years.

The UK’s Bristol Cable receives widespread praise for its local investigations and will soon be celebrating its first anniversary as a media co-operative, with intentions to expand the editorial team as it becomes self-sustaining.

And the Pulitzer and Peabody award-winning ProPublica, although not always locally focused, puts community engagement at the centre of its investigations, this year receiving $2.2 million to expand its crowdsourcing platform.

ProPublica’s Facebook group for their ongoing investigation into patient safety is led by reporter Marshall Allen (Screenshot from Pro Publica on Facebook

True, these are largely non-profit organisations, but that doesn’t mean the same can’t apply to those with shareholders to pay.

“It obviously has a very ‘do-gooder’ aspect to it,” continued Brown, “we’re listening to communities and democracy and all that good stuff, but really the bottom line is to be sustainable.

“This is what all the research is pointing to, news organisations have to get better at engagement. In order to drive loyalty and credibility and all the kind of things that get people to subscribe or get advertisers to pay a decent rate, these are the kind of things you need to be doing. It’s tied to the sustainability of the business I think.”

If profit-making publishers invested in ways to involve their audiences rather than, or in addition to, advertising solutions that alienate and commodify the reader or paywalls that hide quality stories from public view it could not only support the business, but improve the journalism itself.

Of all the subjects included in CUNY’s social journalism MA, verification and social newsgathering is the most important of them all, said Brown.

“The more engaged your community is… you’re also going to get perspectives you wouldn’t maybe get which enhances the accuracy of your reporting. But also you can get them to help you check facts, they are the eyes on the ground for you.”

When the two young broadcast journalists Alison Parker and Adam Ward were gunned down live on air near Roanoke, Virginia in August, The Wall Street Journal’s audience engagement team were central in verifying information and channeling feedback to reporters.

“The audience team is just like your shoe-leather reporters,” Carla Zanoni, head of emerging media and audience development, told the Columbia Journalism Review, “in that they feel like this is what they’ve been training for.”

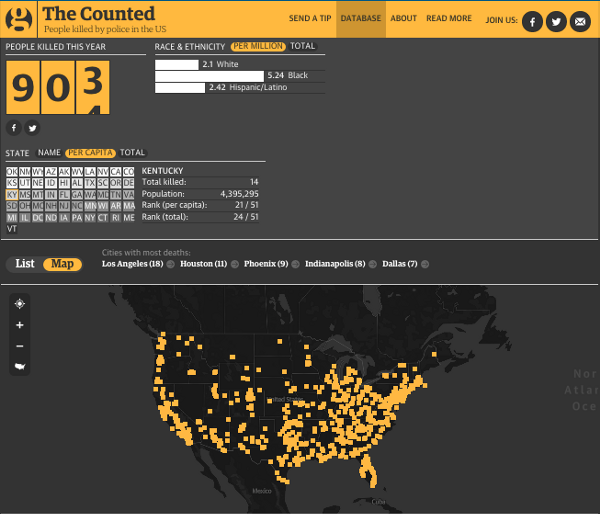

And when the Guardian launched it’s rolling investigation into officer-involved shooting incidents in the US — The Counted — reporters first sought out activists across social media to get a better understanding of the situation and “securing enough legitimacy to form a space of their own”.

Screenshot from the Guardian’s interactive ‘The Counted’, with the invitation to “send a tip” firs tin the menu bar

“It’s become pretty clear that without building a living community of people who care about the issue around the journalism, the journalism would be much less successful,” the Guardian’s US audience director, Mary Hamilton, told the Columbia Journalism Review for the same piece.

The practice should not be limited to non-profits or international news organisations with the budget to experiment though.

For nearly five years, New Jersey resident Justin Auciello has been running a Facebook page reporting storms hitting the Jersey shoreline, working with his community to find and verify information for two NJ counties.

That Facebook page now has almost 230,000 followers with people posting tips and info to the page on a daily basis, a level of interaction and conversation orders of magnitude higher than many local news outlets across the UK.

Auciello chose Facebook because “that’s where everyone was hanging out” and Brown says the same thinking is central to building a community, wherever they happen to be.

Jersey Shore Hurricane News has an impressive following for a one-person newsroom (Screenshot from JSHN on Facebook

“We try to tell [students] to go to where people are,” said Brown. “If your community is very active on Twitter then that’s where you should be, but if they’re only face to face or on Facebook, we try to focus on that aspect of it rather than trying to convince people to use the tools that would be more convenient for the journalist.

“We’re trying to go out there and find people who are already engaging and ask what can we add to that conversation? Where does journalism play a role in that community? What information do they need? That kind of thing.”

And this doesn’t antiquate or supersede the fundamentals of journalism; all journalists still have to know how to phrase questions, structure a story and dig up information.

But when it is now so easy to involve the very people the stories are for and about, why ignore their contribution to the process?

“Each community is different, so it’s been interesting to see what approach is working and what’s not working,” said Brown.

“It’s definitely not a recipe. We can’t tell them here’s the ten things you need to do and it’s going to work if you do it this way.”